Good Samaritan law

Good Samaritan laws offer legal protection to people who give reasonable assistance to those who are, or whom they believe to be injured, ill, in peril, or otherwise incapacitated.[1] The protection is intended to reduce bystanders' hesitation to assist, for fear of being sued or prosecuted for unintentional injury or wrongful death. An example of such a law in common-law areas of Canada: a Good Samaritan doctrine is a legal principle that prevents a rescuer who has voluntarily helped a victim in distress from being successfully sued for wrongdoing. Its purpose is to keep people from being reluctant to help a stranger in need for fear of legal repercussions should they make some mistake in treatment.[2] By contrast, a duty to rescue law requires people to offer assistance and holds those who fail to do so liable.

Good Samaritan laws may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, as do their interactions with various other legal principles, such as consent, parental rights and the right to refuse treatment. Most such laws do not apply to medical professionals' or career emergency responders' on-the-job conduct, but some extend protection to professional rescuers when they are acting in a volunteer capacity.

The principles contained in Good Samaritan laws more typically operate in countries in which the foundation of the legal system is English common law, such as Australia.[3] In many countries that use civil law as the foundation for their legal systems, the same legal effect is more typically achieved using a principle of duty to rescue.

Good Samaritan laws take their name from a parable found in the Bible, attributed to Jesus, commonly referred to as the Parable of the Good Samaritan which is contained in Luke 10:29–37. It recounts the aid given by a traveller from the area known as Samaria to another traveller of a conflicting religious and ethnic background who had been beaten and robbed by bandits.[4]

Regions

Good Samaritan laws tend to differ by region, as each is crafted based on local interpretations of the providers protected, as well as the scope of care covered.

Australia

Most Australian states and territories have some form of Good Samaritan protection. In general, these offer protection if care is made in good faith, and the "Good Samaritan" is not impaired by drugs or alcohol. Variations exist between states, from not applying if the "Good Samaritan" is the cause of the problem (New South Wales), to applying under all circumstances if the attempt is made in good faith (Victoria).[5]

Belgium

The Belgian Good Samaritan Law imposes on anyone who is capable to aid a legal duty to help a person, who is in great danger, without putting himself or others in serious danger (article 422bis Criminal Code).[1]

Canada

In Canada, good Samaritan acts fall under provincial jurisdiction. Each province has its own act, such as Ontario's[6] and British Columbia's[7] respective Good Samaritan Acts, Alberta's Emergency Medical Aid Act,[8] and Nova Scotia's Volunteer Services Act.[9] Only in Quebec, a civil law jurisdiction, does a person have a general duty to respond, as detailed in the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms.[10][11]

An example of a typical Canadian law is provided here, from Ontario's Good Samaritan Act, 2001, section 2:

Protection from liability

2. (1) Despite the rules of common law, a person described in subsection (2) who voluntarily and without reasonable expectation of compensation or reward provides the services described in that subsection is not liable for damages that result from the person's negligence in acting or failing to act while providing the services, unless it is established that the damages were caused by the gross negligence of the person. 2001, c. 2, s. 2 (1).[12]

Yukon and Nunavut do not have good Samaritan laws.

China

There have been incidents in China, such as the Peng Yu incident in 2006,[13][14] where good Samaritans who helped people injured in accidents were accused of having injured the victim themselves.

In 2011, a toddler called Wang Yue was killed when she was run over by two vehicles. The entire incident was caught on a video, which shows eighteen people seeing the child but refusing to help. In a November 2011 survey, a majority, 71%, thought that the people who passed the child without helping were afraid of getting into trouble themselves.[15] Following the event, China Daily reported that "at least 10 Party and government departments and organizations in Guangdong, including the province's commission on politics and law, the women's federation, the Academy of Social Sciences, and the Communist Youth League, have started discussions on punishing those who refuse to help people who clearly need it."[16] Officials of Guangdong province, along with many lawyers and social workers, also held three days of meetings in the provincial capital of Guangzhou to discuss the case. It was reported that various lawmakers of the province were drafting a good Samaritan law, which would "penalize people who fail to help in a situation of this type and indemnify them from lawsuits if their efforts are in vain".[17] Legal experts and the public debated the idea in preparation for discussions and a legislative push.[18] On 1 August 2013, the nation's first good Samaritan law went into effect in Shenzhen.[19] On 1 October 2017, China's national Good Samaritan law came into force, Clause 184 in Civil Law General Principles.[20]

Finland

The Finnish Rescue Act explicitly stipulates a duty to rescue as a "general duty to act" and "engage in rescue activities according to [one's] abilities". The Finnish Rescue Act thus includes a principle of proportionality which requires professionals to extend immediate aid further than laypersons.

The Finnish Criminal Code[21] stipulates:

Section 15 – Neglect of rescue (578/1995)

A person who knows that another is in mortal danger or serious danger to his or her health, and does not give or procure such assistance that in view of his or her options and the nature of the situation can reasonably be expected, shall be sentenced for neglect of rescue to a fine or to imprisonment for at most six months.

France

In France, the law requires anyone to assist a person in danger or at the very least call for help. People who help are not liable for damages except if the damages are intentional or caused by a "strong" mistake.[22][23]

Germany

In Germany, failure to provide first aid to a person in need is punishable under § 323c of its criminal penal code. However, any help one provides cannot and will not be prosecuted even if it made the situation worse or did not fulfill specific first aid criteria. People are thus encouraged to help in any way possible, even if the attempt is not successful.[24] Moreover, people providing first aid are covered by the German Statutory Accident Insurance in case they suffer injury, losses, or damages.[25]

India

There were around 480,000 road accidents in India in 2016, in which 150,000 people were killed. The Good Samaritan law gives legal protection to the good samaritans who help accidents victims with emergency medical care within the 'Golden Hour'. People are thus encouraged to help in any way possible, even if the attempt is not successful.[26]

Ireland

The Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act of 2011[27] introduced legislation specifically addressing the liability of citizen good Samaritans or volunteers in the Republic of Ireland, without introducing a duty to intervene. This act provides for exemption from liability for a person, or voluntary organization, for anything done while providing "assistance, advice or care" to a person who is injured, in serious risk or danger of becoming injured or developing an illness (or apparently so). There are exclusions for cases of "bad faith" or "gross negligence" on behalf of the carer, and incidents relating to the negligent use of motor vehicles. This Act only addresses situations where there is no duty of care owed by the good Samaritan or the volunteer.

The pre-hospital emergency care council (PHECC) specifically addresses the good Samaritan section of the Civil Law Act of 2011 and states that "The use of skills and medications restricted to Registered Practitioners would be covered under the 'Good Samaritan' Act. This Act assumes that you had no intention to practice during this time and that you acted as a Good Samaritan, assisting until the Emergency Services arrive on scene and you can hand over."[28]

Israel

In Israel, the law requires anyone to assist a person in danger or at the very least call for help. People who help in good faith are not liable for damages. Helpers are eligible for compensation for damages caused to them during their assistance.

Japan

In Japan, there are some laws that serve as an equivalent to Good Samaritan laws, for example, article 37 of the penal code, states that:

"An act a person was compelled to take to avert a present danger to the life, body, liberty or property of oneself or any other person is not punishable only when the harm produced by such act does not exceed the harm to be averted; provided, however, that an act causing excessive harm may lead to the punishment being reduced or may exculpate the offender in light of the circumstances."[29]

Another japanese Good Samaritan law appears in Article 698 of the Japanese civil code, where the law offers the helper protection from liability stating that:

"If a manager engages in benevolent intervention in another's business in order to allow a principal to escape imminent danger to the principal's person, reputation, or property, the manager is not liable to compensate for damage resulting from this unless the manager has acted in bad faith or with gross negligence."[30]

However there is an exception, because in Japan health professionals are subject to Duty to Rescue Laws, instead of the good samaritan laws which are applied to other citizens.[31]

Romania

In Romania, the health reform passed in 2006 states that persons without medical training offering basic first aid voluntarily at the indications of a medical dispatch office or from own knowledge of first aid maneuvers, acting in good will to preserve the life or health of another person cannot be held responsible under penal or civil law.

United Arab Emirates

In November 2020, the United Arab Emirates was the first Arab country to pass a Good Samaritan law.[32]

United Kingdom

In the common law of England and Wales there is no criminal liability for failing to act in the event of another person being in danger; however, there are exceptions to this rule. In instances where there has been an assumption of responsibility by the bystander, a dangerous situation was created by them, or there is a contractual or statutory duty to act, criminal liability would be imposed on the bystander for their failure to take action.

The courts are reluctant to penalize people attempting rescue. The Social Action, Responsibility and Heroism Act 2015 helps protect 'good Samaritans' when considering a claim of negligence or a breach of duty.[33] This act is one of the shorter pieces of legislation in the UK with a length of just above 300 words, has thus far never been cited in court since becoming law, and is considered to be vague. The Labour Party at the time of the laws passing criticized it for being valuable in concept but lacking an earnest effort.

United States

All fifty states and the District of Columbia have some type of Good Samaritan law. The details of good Samaritan laws vary by jurisdiction, including who is protected from liability and under what circumstances.[34]

The 1998 Aviation Medical Assistance Act also provided coverage for "Good Samaritans" while in flight.[35]

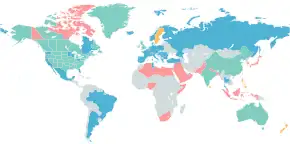

Countries without a Good Samaritan law

The following countries have no Good Samaritan law:

Common features

Good Samaritan laws often sharing different combinations or interpretations of the similar features, which vary by region.

Duty to assist

In some jurisdictions, unless a caretaker relationship (such as a parent-child or doctor-patient relationship) exists prior to the illness or injury, or the "Good Samaritan" is responsible for the existence of the illness or injury, no person is required to give aid of any sort to a victim. Good Samaritan statutes in the states of Minnesota,[40] Vermont[41] and Rhode Island[42] do require a person at the scene of an emergency to provide reasonable assistance to a person in need. This assistance may be to call 9-1-1. Violation of the duty-to-assist subdivision is a petty misdemeanour in Minnesota and may warrant a fine of up to $100 in Vermont. At least five other states, including California and Nevada, have seriously considered adding duty-to-assist subdivisions to their Good Samaritan statutes.[43] New York's law provides immunity for those who assist in an emergency.[44] The public policy behind the law is:

The furnishing of medical assistance in an emergency is a matter of vital concern affecting the public health, safety and welfare. Prehospital emergency medical care, the provision of prompt and effective communication among ambulances and hospitals[,] and safe and effective care and transportation of the sick and injured are essential public health services.

— N.Y. Public Health L. § 3000.[45]

Imminent peril

Good Samaritan provisions are not universal in application. The legal principle of imminent peril may also apply.[46] In the absence of imminent peril, the actions of a rescuer may be perceived by the courts to be reckless and not worthy of protection. To illustrate, a motor vehicle collision occurs, but there is no fire, no immediate life threat from injuries, and no danger of a second collision. If someone, with good intentions, causes injury by pulling the victim from the wreckage, a court may rule that Good Samaritan laws do not apply because the victim was not in imminent peril and hold the actions of the rescuer to be unnecessary and reckless.[47][48]

Reward or compensation

Only first aid provided without the intention of reward or financial compensation is covered. Medical professionals are typically not protected by Good Samaritan laws when performing first aid in connection with their employment.[49] Some states make specific provisions for trained medical professionals acting as volunteers and for members of volunteer rescue squads acting without expectation of remuneration.[44][50] In Texas, a physician who voluntarily assisted in the delivery of an infant, and who proved that he had "no expectation of remuneration", had no liability for the infant's injuries due to allegedly ordinary negligence; there was "uncontroverted testimony that neither he nor any doctor in Travis County would have charged a fee to [the mother] or any other person under the circumstances of this case".[51] It was significant that the doctor was not an employee of the attending physician, but was only visiting the hospital and had responded to a "Dr. Stork" page, and had not asked or expected to be paid.[51]

Obligation to remain

If a responder begins rendering aid, he must not leave the scene until it is necessary to call for needed medical assistance, a rescuer of equal or higher ability takes over, or continuing to give aid is unsafe. This can be as simple as a lack of adequate protection against potential diseases, such as vinyl, latex, or nitrile gloves to protect against blood-borne pathogens. A responder is never legally compelled to take risks to aid another person. The responder is not legally liable for any harm to the person assisted, as long as the responder acted rationally, in good faith, and in accordance with their level of training.[52]

Consent

The responder must obtain the consent of the patient, or of the legal guardian of a patient who is a minor, unless this is not possible; failing to do so may attract a charge of assault or battery.

Implied consent

Consent may be implied if an unattended patient is unconscious, delusional, intoxicated, or deemed mentally unfit to make decisions regarding his or her safety, or if the responder has a reasonable belief that this was so; courts tend to be very forgiving in adjudicating this, under the legal fiction that "peril invites rescue" (as in the rescue doctrine).[53] The test in most jurisdictions is that of the "average, reasonable person". To illustrate, would the average, reasonable person in any of the states described above consent to receiving assistance in these circumstances is able to make a decision?

Consent may also be implied if the legal parent or guardian is not immediately reachable and the patient is not considered an adult.

Parental consent

If the victim is a minor, consent must come from a parent or guardian. However, if the legal parent or guardian is absent, unconscious, delusional, or intoxicated, consent is implied. A responder is not required to withhold life-saving treatment (e.g., CPR or the Heimlich maneuver) from a minor if the parent or guardian will not consent. The parent or guardian is then considered neglecting the minor, and consent for treatment is implied by default because neglect has been committed. Special circumstances may exist if child abuse is suspected (the courts will usually give immunity to those first responders who report what they reasonably consider to be evidence of child abuse or neglect, similar to that given to those who have an actual duty to report such abuse, such as teachers or counsellors).[54]

Laws for first responders only

In some jurisdictions, Good Samaritan laws only protect those who have completed basic first aid training and are certified by health organizations, such as the American Heart Association, or American Red Cross, provided that they have acted within the scope of their training.[55] In these jurisdictions, a person who is neither trained in first aid nor certified, and who performs first aid incorrectly, can be held legally liable for errors made. In other jurisdictions any rescuer is protected from liability so long as the responder acted rationally. In Florida, paramedics, EMTs, and emergency medical responders (first responders) are required by law to act under the Duty to Act law, which requires them to stop and give aid that falls within their practice.

Comparison with duty to rescue

Good Samaritan laws may be confused with the duty to rescue, as described above. U.S. and Canadian approaches to this issue differ. Under the common law, Good Samaritan laws provide a defense against torts arising from the attempted rescue. Such laws do not constitute a duty to rescue, such as exists in some civil law countries,[56] and in the common law under certain circumstances. However, the duty to rescue where it exists may itself imply a shield from liability; for example, under the German law of Unterlassene Hilfeleistung (an offense not to provide first aid when necessary), a citizen is obliged to provide first aid when necessary and is immune from prosecution if assistance given in good faith turns out to be harmful. In Canada, all provinces with the exception of Quebec operate on the basis of English Common Law. Quebec operates a civil law system, based in part on the Napoleonic Code, and the principle of duty to rescue does apply.[57] Similarly, in France anyone who fails to render assistance to a person in danger will be found liable before French courts (civil and criminal liability). The penalty for this offence in criminal courts is imprisonment and a fine (under article 223–6 of the Criminal Code) while in civil courts judges will order payment of pecuniary compensation to the victims.[58]

To illustrate a variation in the concept of duty to rescue, in the Canadian province of Ontario, the Occupational Health and Safety Act provides all workers with the right to refuse to perform unsafe work. There are, however, specific exceptions to this right. When the "life, health or safety of another person is at risk", then specific groups, including "police officers, firefighters, or employees of a hospital, clinic or other type of medical worker (including EMS)" are specifically excluded from the right to refuse unsafe work.[59]

References and notes

- "The Good Samaritan Law across Europe". DAN Legal Network. Archived from the original on 2021-04-20. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- "What Are Good Samaritan Laws?". Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- Gulam, Hyder; Devereux, John (2007). "A Brief Primer on Good Samaritan Law for Health Care Professionals". Australian Health Review. 31 (3): 478–482. doi:10.1071/AH070478. PMID 17669072. Archived from the original on 2007-08-30.

- "Good Samaritan". Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Law. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- Bird, Sara (July 2008). "Good Samaritans" (PDF). Australian Family Physician. 30 (7): 570–751. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "Good Samaritan Act, S.O., 2001 (Ontario E-laws website)". 24 July 2014. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- "Good Samaritan Act [RSBC 1996] CHAPTER 172 (British Columbia Queen's Printer website)". Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- "Emergency Medical Aid Act (Alberta Queen's Printer website". 17 September 2012. Retrieved 2014-09-29.

- "Volunteer Services Act 'Good Samaritan' RSNS 1989 (amend. 1992) (Nova Scotia Legislature website)". Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- "Quebec Charter of Rights and Freedom". Éditeur officiel du Québec. Retrieved 2012-07-18.

- "Good Samaritan Law from The Canadian Association of Food Banks". Canadian Association of Food Banks (via Internet Archive). Archived from the original on 2007-12-17. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- "Good Samaritan Act, 2001". Queen's Printer for Ontario, 2005. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007. Retrieved December 26, 2005.

- "A 45,000-yuan helping hand: common sense, decency, and crowded public transportation". Danwei.org. September 7, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-10.

- "Ignored toddler doesn't tell the whole story about China". The Globe and Mail. Oct 19, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-10-19.

- "Youths Search Their Souls after Yue Yue's Death". China.org.cn. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- Zheng, Caixiong (20 October 2011). "Law mulled to make aid compulsory". chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Demick, Barbara (21 October 2011). "Chinese toddler's death evokes outpouring of grief and guilt". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Chin, Josh (October 22, 2011). "Toddler's Death Stirs Ire in China". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- Huifeng, He (1 August 2013). "Shenzhen Introduces Good Samaritan Law". South China Morning Post. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- "The Good Samaritan Law Comes into Effect". October 1, 2017.

- "FINLEX ® - Translations of Finnish acts and decrees: 39/1889 English". finlex.fi.

- Legifrance.gouv.fr https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/id/LEGIARTI000042083934/2020-07-05. Retrieved 2022-12-28.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Legifrance.gouv.fr https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/article_lc/LEGIARTI000037289588. Retrieved 2022-12-28.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - (in German) § 323c Unterlassene Hilfeleistung (Strafgesetzbuch – stgb) [Omission to effect an easy rescue]. (in English) English version.

- Sozialgesetzbuch 7. §2, §13.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - "Good Samaritan | Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India".

- Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2011, s. 4: Liability for negligence of good samaritans, volunteers and volunteer organisations (No. 23 of 2011, s. 4). Enacted on 2 August 2011. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book.

- "Good Samaritan". Pre-hospital emergency care council.

- "Penal Code - English - Japanese Law Translation". www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- "Civil Code - English - Japanese Law Translation". www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- "Medical Practitioners' Act - English - Japanese Law Translation". www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- "An Overview Guide on Good Samaritan Law in the United Arab Emirates".

- "Social Action, Responsibility and Heroism Act 2015", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 2015 c. 3, retrieved 8 May 2020

- The laws include: Maryland Courts and Judicial Proceedings Code § 5-603; VA § 8.01-225; NC § 20-166 and § 90-21.14; SC § 15-1-310; TN 63-6-218; GA § 51-1-29; Long list for 50 states: https://recreation-law.com/2014/05/28/good-samaritan-laws-by-state/

- "AMAA". Act of 1998 (PDF). Section 5b.

- Need for Good Samaritan law, 12 February 2022

- How and when to be a Good Samaritan, 13 March 2019

- Bell, Ross (2015-08-31). "New Zealand needs to do more to tackle overdose problem". Stuff. Retrieved 2022-12-10.

- "Written Answer by Minister for Law, K Shanmugam, to Parliamentary Question on the introduction of a Good Samaritan law in Singapore". Singapore Ministry of Law. 14 February 2012.

- 604A.01 MINNESOTA GOOD SAMARITAN LAW Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- "Vermont Good Samaritan Law". Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- Rhode Island Chapter 11-56-1 – Duty to assist. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- Lyons, Donna (1999-03-01). "Help Your Neighbor—It's the Law". State Legislatures. Archived from the original on 2007-09-07. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- N.Y. Public Health L. §§ 3000-a, 3000-b, 3013 (McKinney 2000); see also NY State Assembly website database of law. Accessed July 25, 2011.

- N.Y. Public Health L. § 3000 (McKinney 2000); see also NY State Assembly website database of law. Accessed July 25, 2011.

- "What is the Good Samaritan Law? (essortment website)". Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- "Good Samaritan law may not apply (USA Today)". 2007-03-23. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- See also, California Supreme Court decision in Van Horn vs. Torti, December 18, 2008, with a similar fact pattern and limitation of protection to medical personnel rendering medical aid.

- "RCW 4.24.300 Immunity from liability for certain types of medical care (Washington State Legislature website)". Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- "Colorado Good Samaritan Law". Archived from the original on 2008-07-23. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- McIntyre v. Ramirez Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, 109 S.W.3d 741 (Tex. Sup. Ct. 2003), overturning 59 S.W.3d 821 (Tex. Ct. of Appeals) and citing Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 74.001 (effective in 1998, and since amended). Accessed July 25, 2011.

- Rolfsen, M. L. (2007). "Medical care provided during a disaster should be immune from liability or criminal prosecution". The Journal of the Louisiana State Medical Society. 159 (4): 224–225, 227–229. PMID 17987961.

- "Implied Consent". Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- Foltin GL, Lucky C, Portelli I, et al. (June 2008). "Overcoming legal obstacles involving the voluntary care of children who are separated from their legal guardians during a disaster". Pediatric Emergency Care. 24 (6): 392–398. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e318178c05d. PMID 18562886. S2CID 24058314.

- "Good Samaritan/Fireman's Rule". Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- Higuchi, N. (March 2008). "[Good Samaritan Act and physicians' duty to rescue]". Nippon Hoshasen Gijutsu Gakkai Zasshi (in Japanese). 64 (3): 382–4. doi:10.6009/jjrt.64.382. PMID 18434681.

- "Helping Someone in Danger: Good Samaritan Laws". Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- Audrey Laur (March 2013). "Liabilities of Doctors on Aircraft". Medico-Legal Journal. 81 (Pt 1): 31–35. doi:10.1177/0025817213475386. PMID 23492892. S2CID 7890965.

- "Occupational Health and Safety Act, R.S.O. (1990) (Ontario E-laws website)". Retrieved 2008-10-10.