K-class blimp

The K-class blimp was a class of blimps (non-rigid airship) built by the Goodyear Aircraft Company of Akron, Ohio for the United States Navy. These blimps were powered by two Pratt & Whitney Wasp nine-cylinder radial air-cooled engines, each mounted on twin-strut outriggers, one per side of the control car that hung under the envelope. Before and during World War II, 134 K-class blimps were built and configured for patrol and anti-submarine warfare operations, and were extensively used in the Navy’s anti-submarine efforts in the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean areas.

| K-class | |

|---|---|

| |

| Role | Patrol airship |

| Manufacturer | Goodyear-Zeppelin and Goodyear Aircraft Corporation |

| First flight | 6 December 1938 |

| Retired | 1959 |

| Primary user | United States Navy |

| Number built | 134 |

Development

In 1937, K-2 was ordered from Goodyear as part of a contract that also bought the L-1, (Goodyear’s standard advertising and passenger blimp). K-2 was the production prototype for future K-class airship purchases. K-2 flew for the first time at Akron, Ohio on December 6, 1938[1] and was delivered to the Navy at NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey on December 16. The envelope capacity of the K-2—404,000 ft³ (11,440 m³)—was the largest for any USN blimp up to that time. K-2 was flown extensively as a prototype, and continued to operate testing new equipment, techniques, and performing whatever tasks were needed, including combat patrols in World War II.

On October 24, 1940, the Navy awarded a contract to Goodyear for six airships (K-3 through K-8) that were assigned the designation Goodyear ZNP-K. These blimps were designed for patrol and escort duties and were delivered to the Navy in late 1941 and early 1942. K-3 through K-8 had only minor modifications to K-2's design, the only major change was in engines from Pratt & Whitney R-1340-16s to Wright R-975-28s. The Wright engine/propeller combination proved excessively noisy and was replaced in later K-ships with slightly modified Pratt & Whitney engines. The K-3 cost $325,000.[2] A series of orders for more K-class blimps followed. Twenty-one additional blimps (K-9 through K-30) were ordered on 14 October 1942. On 9 January 1943, 21 more blimps (K-31 through K-50) were ordered. The envelope size of K-9 through K-13 was increased to 416,000 ft³ (11,780 m³) and those delivered thereafter used an envelope of 425,000 ft³ (12,035 m³). The final contract for the K-class blimp were awarded in mid-1943 for 89 airships. Four blimps from this order were later canceled. The remaining deliveries were assigned numbers K-51 through K-136. But, the number K-136 was not assigned to a specific airship as the control car assigned for K-136 was used to replace the car for K-113. The original car for K-113 was destroyed in a fire.

The US Navy's experiences with K-ships in tropical regions showed a need for a blimp with greater volume than the K-class to offset the loss of lift due to high ambient temperatures. Goodyear addressed these concerns with a follow-on design, the M-class blimp, which was 50% larger.

Variants

After World War II a number of K-class blimps were modified with more advanced electronics, radar, sonar systems and larger envelopes. These modified blimps were designated:

- ZNP-K

- The original designation of the K-class blimps. Individual blimps were identified by a sequential suffix number, e.g. ZNP-K-2, ZNPK-8 etc. In everyday use only the K and numerical suffixes were used. Batches of blimps were built with sometimes major differences, but the designations remained in the ZNP-K range, until the later versions, listed below, emerged.

- ZPK

- Revised designation of the ZNP-K series.

- ZP2K

- A larger envelope with the volume increased to 527,000 cu ft (14,900 m3), sensors and other improvements re-designated ZSG-2.

- ZP3K

- A larger envelope with the volume increased to 527,000 cu ft (14,900 m3), with systems and controls even more advanced than the ZP2Ks, re-designated ZSG-3.

- ZP4K

- Delivered in 1953, retaining the 527,000 cu ft (14,900 m3) envelope volume and length of 266 ft (81.08 m), re-designated ZSG-4 in 1954.

Operational history

The K-ships were used for anti-submarine warfare (ASW) duties in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans as well as the Mediterranean Sea.[3] All equipment was carried in a forty foot long control car. The installed communications and instrumentation equipment allowed night flying. The blimps were equipped with the ASG radar, that had a detection range of 90 mi (140 km), sonobuoys, and magnetic anomaly detection (MAD) equipment. The K-ships carried four 350 lb (160 kg) depth bombs, two in a bomb bay and two externally, and were equipped with a machine gun in the forward part of the control car. An aircrew of 10 normally operated the K-ships, consisting of a command pilot, two co-pilots, a navigator/pilot, airship rigger, an ordnanceman, two mechanics, and two radiomen.

On 1 June 1944, two K-class blimps of United States Navy (USN) Airship Patrol Squadron 14 (ZP-14)[4] completed the first transatlantic crossing by non-rigid airships.[5] K-123 and K-130 left South Weymouth, MA on 28 May 1944 and flew approximately 16 hours to Naval Station Argentia, Newfoundland. From Argentia, the blimps flew approximately 22 hours to Lajes Field on Terceira Island in the Azores. The final leg of the first transatlantic crossing was about a 20-hour flight from the Azores to Craw Field in Port Lyautey (Kenitra), French Morocco. The first pair of K-ships were followed by K-109 & K-134 and K-112 & K-101 which left South Weymouth on 11 and 27 June 1944, respectively. These six blimps initially conducted nighttime anti-submarine warfare operations to complement the daytime missions flown by FAW-15 aircraft (PBYs and B-24s) using magnetic anomaly detection to locate U-boats in the relatively shallow waters around the Straits of Gibraltar. Later, ZP-14 K-ships conducted minespotting and minesweeping operations in key Mediterranean ports and various escort missions including that of the convoy carrying Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill to the Yalta Conference in early 1945. In late April 1945, K-89 and K-114 left Weeksville NAS in North Carolina and flew a southern transatlantic route to NAS Bermuda, the Azores, and Port Lyautey where they arrived on 1 May 1945 as replacements for Blimp Squadron ZP-14.[6]

The ability of the K-ships to hover and operate at low altitudes and slow speeds resulted in detection of numerous enemy submarines as well as assisting in search and rescue missions. The K-ships had an endurance capability of over 24 hours which was an important factor in the employment of ASW tactics.

The mooring system for the K-ship was a 42 ft (12.8 m) high triangular mooring mast that was capable of being towed by a tractor. For advance bases where moving the mooring mast was not needed, a conventional stick mast was used. A large ground crew was needed to land the blimps and moor them to the mast.

During the war, one K-ship—K-74—was lost to enemy action when it was shot down by U-134 in the Straits of Florida on 18 July 1943. The crew was rescued eight hours later, except for one man who was attacked by a shark and drowned just prior to the rescue.[7][8]

In 1947, Goodyear acquired the former Navy K-28 and operated it as part of its commercial advertising blimp fleet. The K ship was named Puritan and was the largest ever Goodyear blimp. The airship was purchased from the Navy primarily to experiment with Trans-Lux illuminated running copy advertising signs attached to the envelope. Costly to operate and maintain, The Puritan was retired from the Goodyear fleet in April, 1948 after only one year of operation. The blimp was deflated and placed in storage at Goodyear's base at Wingfoot Lake in Suffield, Ohio and was later sold back to the Navy.

K-43, the last operational Navy "K Ship", was retired from service in March, 1959.

Nuclear weapon effects tests

Several K-class blimps were used for nuclear weapon effects tests at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) during the Operation Plumbbob series of tests in 1957. K-40, K-46, K-77 and K-92 were destroyed in Project 5.2, events Franklin (Fissile) and Stokes (19 kt, XW-30 device).[9] The tests were to "determine the response characteristics of the model ZSG-3 airship when subject to a nuclear detonation in order to establish criteria for safe escape distances after airship delivery of antisubmarine warfare special weapons."[10] According to the Navy, the "airship operations were conducted with extreme difficulty."[11] The Navy was trying to determine whether the airship could be among the aircraft to deliver its planned Lulu (W-34) nuclear depth charge.[12]

Airship designations

During the life of the K-class airship, the U.S. Navy used three different designation systems. From 1922 through World War II, the Navy used a four character designator. The K-class blimps were designated ZNP-K where the "Z" signified lighter-than-air; "N" denoted non-rigid; "P" denoted a patrol mission; and "K" denoted the type or class of airship.

In April 1947, the General Board of the U.S. Navy modified the designation system for airships. The second character of the designator was dropped as the Board dropped the code for rigid airships so that the "N" for non-rigid was no longer needed. The designation for the K-class blimps then became ZPK.

In April 1954, the designation system for lighter-than-air airships was further modified so that it conformed to the designation system for heavier-than-air aircraft. By this time the ZPK blimps had been retired from service and only the later version K-Class blimps were in service. Under the 1954 system the ZP2K blimp became the ZSG-2, the ZP3K became the ZSG-3, the ZP4K became the ZSG-4, and the ZP5K became the ZS2G-1. In new designation system, the "Z" signified lighter-than-air; the "S" was the type denoting an anti-submarine warfare mission; the numeral (i.e., "2") was the model; and the "G" was for Goodyear, the manufacturer's letter in the Navy's designation system. The final numeral denoted the series of the vehicle within the type/model. The US Navy ordered a new type of airship in 1951 for the Korean War. The new air ship was designated ZP4K (later called ZSG-4), which had a different design than WW2 K-type. The first ZP4K was delivered in June 1954. A total of 15 were built. In 1955 an update version a called the ZP5K (later called ZS2G-1) was delivered, a total of 15 were built. The ZP5K has an inverted “Y” tail.[13][14]

Surviving aircraft

- K-28 Goodyear Puritan – Control car on static display at the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, Connecticut.[15]

- K-47 – Control car on static display at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.[16] The K-47 was upgraded to the ZP3K configuration before it was retired in 1956.[17]

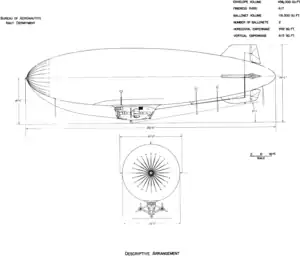

Specifications (K-14)

General characteristics

- Crew: 9–10

- Length: 251 ft 8 in (76.73 m)

- Diameter: 57 ft 10 in (17.63 m)

- Volume: 425,000 cu ft (12,043 m3)

- Useful lift: 7,770 lb (3,524 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney R-1340-AN-2 radials , 425 hp (317 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 78 mph (125 km/h, 68 kn)

- Cruise speed: 58 mph (93 km/h, 50 kn)

- Range: 2,205 mi (3,537 km, 1,916 nmi)

- Endurance: 38 hours 12 minutes

Armament

- 1 × .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine gun

- 4 × 350 lb (160 kg) AN-Mk 47 depth charges

See also

References

| External video | |

|---|---|

Notes

- Grossnick, Roy A., ed. (1987). "Pre-WW II Blilmps and the Evolution of the K-class and WW II Airships". Kite Balloons to Airships: The Navy's Lighter-than-Air Experience. Washington, D.C.: Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Air Warfare) and the Commander, Naval Air Systems Command. p. 35.

- Crestview, Florida, "U. S. Navy Gets World's Largest Blimp", Okaloosa News-Journal, Friday 31 October 1941, Volume 27, Number 42, page 3.

- André., Baptiste, Fitzroy (1988). War, cooperation, and conflict : the European possessions in the Caribbean, 1939–1945. New York: Greenwood Press. pp. 161. ISBN 9780313254727. OCLC 650310469.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Blimp Squadron 14". Archived from the original on 2009-11-13. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- "Kaiser, Don, K-Ships Across the Atlantic, Naval Aviation News, Vol. 93(2), 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-17. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

- Kline, R. C. and Kubarych, S. J., Blimpron 14 Overseas, 1944, Naval Historical Center, Navy Yard, Washington, D. C.

- Vaeth, J. Gordon "Incident in the Florida Straits" United States Naval Institute Proceedings (August 1979) pp.84–86

- defensemedianetwork.com, Blimp vs. U-boat, By Robert F. Dorr - October 11, 2017

- Defense Nuclear Agency, Plumbob Series 1957 DNA 6005F, Washington D.C., pages 6–7, 41–42, 45, 82

- Defense Nuclear Agency, Plumbob Series 1957 DNA 6005F, Washington D.C., page 133

- Defense Nuclear Agency, Plumbob Series 1957 DNA 6005F, Washington D.C., page 133

- Hansen, Chuck, The Swords of Armageddon, 1995, Chuckelea Publications, Sunnyvale, California, Volume VII, page 456

- globalsecurity.org Airship

- history.navy.mil, XV. Airship Types in the Postwar Period

- "Goodyear ZNPK-28 Blimp Control Car". New England Air Museum. New England Air Museum. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- "K-47 CONTROL CAR". National Naval Aviation Museum. Naval Aviation Museum Foundation. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Shock, James R., U.S. Navy Airships 1915–1962, 2001, Atlantis Productions, Edgewater Florida, ISBN 978-0963974389, page 113

Bibliography

- Althoff, William F. (1990). Sky Ships. New York: Orion Books. ISBN 0-517-56904-3.

- Althoff, William F. (2009). Forgotten weapon: U.S. Navy airships and the U-boat war. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 419. ISBN 978-1-59114-010-8.

- Shock, James R. (2001). U.S. Navy Airships 1915–1962. Edgewater, Florida: Atlantis Productions. ISBN 0-9639743-8-6.

- United States Navy K-Type Airships Pilot's Manual (PDF). Akron, Ohio: Goodyear Aircraft Corporation. September 1943. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- Vaeth, J. Gordon (1992). Blimps & U-Boats. Annapolis, Maryland: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-876-3.

See also

- Naval Air Station Hitchcock, Texas

- US Navy airships during World War II

- United States Navy K-Type Airships Pilot’s Manual

Related lists