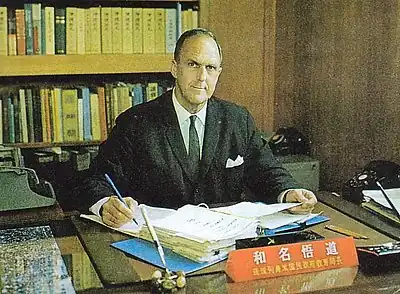

Gordon Warner

Gordon Warner (1913 – March 4, 2010)[1][2] was an American one-legged swordsman who became the highest-ranked westerner in the Japanese martial art of kendo.[3][4] He was also a world-record-holding breaststroke swimmer, a decorated World War II Marine officer, an academic in educational administration, and an author of books on kendo, the culture of Japan, and the history of the Ryukyu Islands.

Early life and war service

Warner grew up among Nisei in Long Beach, California, and began watching Samurai cinema and studying Japanese martial arts as a teenager.[5][3] Tall and athletic, he became captain of the University of Southern California swim team,[6] and lived in a Japanese dorm.[5] On graduating in 1936 with a bachelor's degree in social science he joined the United States Marine Corps Reserve as a second lieutenant. At the urging of two senior officers, lieutenant colonel Anthony Biddle and captain Chesty Puller, he traveled to Tokyo in 1937 to continue his studies in Japanese martial arts. He became a student of Moriji Mochida and Masuda Shinsuke, and reached the rank of shodan in kendo two years later, also beginning to learn iaido,[6] but had to leave Japan in haste after the Kenpeitai learned from his correspondence that he was a Marine officer.[5] From 1939 to 1941, Warner was a teacher and swimming coach in Hawaii, at the Punahou Academy in Honolulu and then at Maui High School. In an exhibition event of the Palama invitational swim meet in Honolulu in 1939, he set the world record for the 220-yard breaststroke, previously held by Leonard Spence, with a time of 2:51.5.[6][7]

In 1941 he was called to United States Marine Corps service as a combat instructor at the Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia. He was later deployed to the South Pacific,[6] where his fluency in the Japanese language allowed him to understand spoken orders from the Japanese and to confuse Japanese soldiers with false orders of his own.[8] He became the first to raise the American flag on Bougainville Island in the Landings at Cape Torokina in November 1943.[6] Less than a week later he lost his left leg when a tank he was commanding was attacked after taking out six machine gun nests.[6][8][9] He was awarded the Navy Cross for his heroism in this battle,[8][9] and the Purple Heart for being injured while serving.[10]

Later life and professional career

Warner retired from the Marines as a lieutenant colonel.[11] He returned to civilian life and to the University of Southern California, where he earned master's degrees in 1944 and again in 1950.[6][12] His 1950 thesis for a Master of Arts in history was Artificial limb development: A history of the Northrop Artificial Limb Research Department 96, Project 17, founded on prosthesis development.[11] From 1950 to 1954 he studied education at the University of California, Berkeley, completing a doctorate in 1954 with the dissertation History of the continuation education program in California.[6][12] At this time he also took up kendo again, despite his missing leg.[6] With Benjamin Hazard he helped found two of the first post-war Kendo groups in the US, in Berkeley in the spring of 1953 and again in Oakland, California in the fall of the same year.[13]

After completing his doctorate he became an assistant professor at California State University, Long Beach. He traveled to Japan in 1956 to attend an international kendo match between American and Japanese kendo masters, hosted a return match in Long Beach in 1957, and continued visiting Japan repeatedly in subsequent years.[6] He remained at Long Beach State until 1964, as coach of swimming and water polo and as chair of the department of educational administration.[14]

In 1964, Warner retired from his faculty position to become the director of the Education Department of the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands, on Okinawa Island.[5] In the early 1970s he was the historian and curator of the US Armed Forces Museum on Okinawa, which closed in 1976.[15] He continued practicing kendo, eventually reaching the 7th dan.[5][3] He also reached the 6th dan in iaido.[3] In 2001 the emperor of Japan awarded him the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 3rd class, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon, for his accomplishments in the martial arts.[5]

Warner died on Okinawa on March 4, 2010,[2] and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[10] He was married and had two children, a son Ion Musashi Warner and a daughter Irene Tomoe Cooper.[2][3]

Books

Warner's books include:

- This Is Kendo: The Art of Japanese Fencing (with Junzō Sasamori, 1964)[16]

- Japanese Festivals (with Hideo Haga, 1968)

- History of Education in Postwar Okinawa (1972)

- Japanese Swordsmanship: Technique and practice (with Donn F. Draeger, 1982)

- The Okinawa War (1985)[17]

- The Okinawan Reversion Story: War, Peace, Occupation, Reversion, 1945-1972 (1995)[18]

- Dining in Chopstick Societies (2007)[5]

References

- Birth date from VIAF authority control record, accessed December 29, 2019

- Stroud, Robert (April 2010), "Gordon Warner, in Memory", The Iaido Journal, retrieved December 29, 2019

- Harstad, Leiv (August 7, 2009), "Gordon Warner", kenshi 24/7

- Larkins, Damian (March 24, 2016). "Kendo: The way of the sword keeping skills sharp". ABC News. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- Allen, David (January 29, 2007), "Veteran writes book on proper chopstick use", Stars and Stripes

- "The one-legged swordsman", Black Belt, pp. 18–24, January 1962

- "Pal swimmers win; Warner sets new pro breast record", Nippu Jiji, p. 11, May 12, 1939

- Chapin, John C., "Top of the Ladder: Marine Operations in the Northern Solomons", Marines in World War II Commemorative Series, Marine Corps History and Museums Division, retrieved December 29, 2019 – via National Park Service

- United States Marine Corps (1948), Bougainville and the Northern Solomons, Historical Sect., Division of Public Information, Headquarters, Marine Corps, pp. 15, 44

- Cooper, Irene Tomoe (April 17, 2013), Dr. Gordon Warner, USMC, Navy Cross, Purple Heart, Arlington National Cemetery, YouTube, archived from the original on December 14, 2021

- Warner, Gordon (1950), Artificial limb development: A history of the Northrop Artificial Limb Research Department 96, Project 17, founded on prosthesis development, USC Libraries

- Register, vol. 2, University of California, 1954, p. 128

- Schmidt, Richard J. (1982), "The historical development of kendo in the United States", Research Journal of Budo, 14 (2): 23–24, doi:10.11214/budo1968.14.2_23

- Roster of staff, California State University, Long Beach, retrieved December 28, 2019

- Cary, Norman Miller (1975), Guide to U.S. Army Museums and Historic Sites, Center of Military History, Department of the Army, p. 31

- This Is Kendo: Tuttle Publishing, 1964, ISBN 0-8048-1607-7. Reviewed by Hazard, Benjamin H. (July–September 1968), Journal of the American Oriental Society, 88 (3): 625–626, doi:10.2307/596925, JSTOR 596925, S2CID 164024174

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - Bond, Bill (December 13, 1992), "A visit back in time to a war hero's stand", Orlando Sentinel

- "War, peace, occupation, reversion reviewed", Japan Update, May 9, 1998