Governor-General of the Irish Free State

The Governor-General of the Irish Free State (Irish: Seanascal Shaorstát Éireann) was the official representative of the sovereign of the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1936. By convention, the office was largely ceremonial. Nonetheless, it was controversial, as many Irish Nationalists regarded the existence of the office as offensive to republican principles and a symbol of continued British involvement in Irish affairs, despite the Governor-General having no connection to the British Government after 1931. For this reason, the office's role was diminished over time by the Irish Government.

| Governor-General of the Irish Free State Seanascal Shaorstát Éireann | |

|---|---|

| |

| Style | His Excellency |

| Residence | Viceregal Lodge |

| Appointer | Monarch of the Irish Free State:

|

| Precursor | Lord Lieutenant of Ireland |

| Formation | 6 December 1922 |

| First holder | Tim Healy |

| Final holder | Domhnall Ua Buachalla |

| Abolished | 11 December 1936 |

| Succession | Executive Council of the Irish Free State[1] |

The 1931 enactment in London of the Statute of Westminster gave the Irish Free State full legislative independence. However, the Irish considered that full legislative independence had been achieved in 1922. The role of Governor-General in the Irish Free State was removed from the Constitution on 11 December 1936,[2] at the time of Edward VIII's abdication as king of the United Kingdom and all the Dominions.

Governors-General of the Irish Free State (1922–36)

| No. | Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Term of office | Monarch | President of Exec. Council | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Took office | Left office | Time in office | |||||

| 1 |  |

Tim Healy (1855–1931) |

6 December 1922 | 31 January 1928 | 5 years, 56 days | George V | Cosgrave |

| 2 |  |

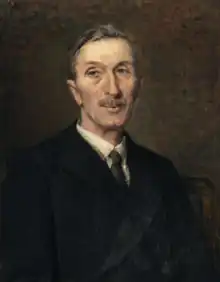

James McNeill (1869–1938) |

31 January 1928 | 1 November 1932 | 4 years, 275 days | Cosgrave De Valera | |

| 3 |  |

Domhnall Ua Buachalla (1866–1963) |

27 November 1932 | 11 December 1936 | 4 years, 14 days | George V Edward VIII |

De Valera |

Selection

The governor-general was appointed by the King on the advice of his Irish ministers. Initially, the British government had some involvement in the appointment process. However, this ended following the 1926 Imperial Conference; thenceforth, only the government of the Irish Free State was formally involved. A further effect of the 1926 conference (in particular, of the Balfour Declaration) was that the monarch also ceased to receive formal advice from the British government in relation to his role in the Irish Free State; such advice thenceforth came officially only from the Executive Council of the Irish Free State (the Cabinet).

The Free State constitution did not limit the governor-general to a fixed term of office. But, in 1927, the Irish government decided that no governor-general would serve a term longer than five years.

Role

Under the constitution of the Irish Free State, the governor-general was bound to act in accordance with the "law, practice and constitutional usage" relevant to the Governor General of Canada. His formal duties included the following:

- Executive authority: The executive authority of the state was formally 'vested' in the king, but exercised by the governor-general on the advice of the Executive Council.

- Appointment of the Cabinet: The President of the Executive Council (prime minister) was appointed by the governor-general after being selected by Dáil Éireann (the lower house of parliament). The remaining ministers were appointed on the nomination of the president, subject to a vote of consent in the Dáil.

- Convention and dissolution of the legislature: The governor-general, on behalf of the king, convened and dissolved the Oireachtas on the advice of the Executive Council.

- Signing bills into law: The king was formally, along with the Dáil and the Seanad, one of three components of the Oireachtas. No bill could become law until it received Royal Assent, given by the governor-general on behalf of the king. The governor-general theoretically had the right to veto a bill or reserve it "for the signification of the King's pleasure", in effect postponing a decision on whether or not to enact the bill, for a maximum of one year. When it was suggested in the House of Lords that the Land Bill 1926 be vetoed in this way, the Lord Chancellor said, "It would not be effective, for if this Bill were vetoed a similar Bill could be passed to-morrow".[3]

- Appointment of judges: All judges were appointed by the governor-general on the advice of the Executive Council.

Until 1928, the governor-general served an additional role as the British government's agent in the Free State. This meant that all official correspondence between the British and Irish governments went through the governor-general and that he had access to British government papers. It also meant that he could receive secret instructions from the British government and so, for example, on assuming office Tim Healy was formally advised by the British government to veto any law that attempted to abolish the controversial Oath of Allegiance to the Crown, sworn by Irish parliamentarians.

However, at the same imperial conference from which the change in the mode of the governor-general's appointment arose, it was agreed that thenceforth the governors-general of Dominions such as the Free State would lose the second half of their dual role and no longer be representatives of the British government, with this role being carried out instead by high commissioners. Furthermore, because, under the changes agreed, the British government lost the right to advise the king in relation to the Irish Free State, it could no longer issue binding instructions to the Irish governor-general.

The first two governors-general lived at the Viceregal Lodge (now known as Áras an Uachtaráin, the official residence of the President of Ireland). The last governor-general resided in a specially leased private residence in Booterstown, County Dublin. The governor-general was officially referred to as His Excellency. However, unlike all the other governors-general within the British Empire in the 1920s and 1930s, none of the Governors-General of the Irish Free State were ever sworn in as members of the Imperial Privy Council. Among all the governors-general in the British Empire at that time, none of the governors-general of the Irish Free State ever wore, in public at least, the official ceremonial uniform for someone of their rank.

History

Origins

The Irish Free State was officially established on 6 December 1922, under the terms of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty. While Irish political leaders favoured the creation of a republic, 'the Treaty' required, instead, that the new state would be a Dominion within the British Empire under a form of constitutional monarchy. Central to the agreed system of government was to be a "representative of the Crown". The new office was not named in the treaty, but the committee charged with drawing up the Free State constitution, under General Michael Collins, decided, after considering a number of names, including "Commissioner of the British Commonwealth"[4] and "President of Ireland",[5] that the representative would bear the title of "Governor-General", the same as that used by the Crown's representative in other Dominions, i.e. Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. However, the Irish language title was Seanascal,[6] meaning "high steward", which was later used in English.[7]

The Crown's representative was expressly bound by the same constitutional conventions as the Governor General of Canada, which would limit him to a largely ceremonial role. It was hoped that, if he was given the same title as that used in other Dominions, then, if the British government attempted to violate convention by using the Office of Governor-General to interfere in the Free State's affairs, these other nations would see their own autonomy threatened and might object.

Cosgrave executive

The first two Governors-General of the Irish Free State assumed office under the pro-Treaty, Cumann na nGaedheal government of W. T. Cosgrave. When it came to choosing the first governor-general, there was speculation about a number of possible candidates, including the famed Irish painter Sir John Lavery and Edward, Prince of Wales. However, the Irish cabinet let it be known that it wished Tim Healy, a former Irish Parliamentary Party MP, to be appointed, and the British government ultimately agreed.

When it came to selecting Healy's successor, the Irish cabinet chose James McNeill, an Ulsterman, from one of the six out of nine Ulster counties which had remained in the Union with Britain, who was a former member of Collins's constitution committee and a former Chairman of Dublin County Council. Because, unlike his predecessor, he was not the United Kingdom's official representative in the Free State, but merely the personal representative of the King, McNeill found himself with less influence than Healy had possessed.

De Valera executive

After the 1932 general election, the Cosgrave government left office and was succeeded by the anti-treaty Fianna Fáil party of Éamon de Valera, who now became President of the Executive Council. Fianna Fáil's immediate goal was to republicanise the Irish Free State and, as such, it opposed the very existence of the governorship-general. With this in mind, de Valera's cabinet decided to boycott and humiliate McNeill at every turn. This policy was followed, for example, during the Eucharistic Congress in 1932, when McNeill was sidelined and, on one occasion, the army's band was withdrawn from a function that he attended. On another occasion, two ministers publicly stormed out of a diplomatic function in Dublin when McNeill arrived as the guest of the French government. In late 1932, de Valera and McNeill clashed when the Governor-General published his private correspondence with de Valera and de Valera sought McNeill's dismissal. King George V, however, acting as peacemaker, persuaded de Valera to withdraw the request on the basis that McNeill was due to finish his term of office within a few weeks. He then persuaded McNeill to bring forward his retirement to 1 November 1932.

On McNeill's retirement, de Valera advised the King to appoint the aged Domhnall Ua Buachalla, a former Fianna Fáil TD, to the post. The new Governor-General (who almost always styled himself as Seanascal) was formally advised by the cabinet to withdraw from public life and confine himself to formal functions such as giving Royal Assent, issuing proclamations, dissolving Dáil Éireann, and appointing, on de Valera's advice, ministers to the Executive Council. In 1933, constitutional amendments were passed removing the Governor General's role in recommending the appropriation of money and the power to veto legislation.

Abolition

In December 1936, when King Edward VIII abdicated from all his thrones, including that of the Irish Free State (as created in the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act and Statute of Westminster 1931), the Irish cabinet decided to finally abolish the governorship-general. Taoiseach John A. Costello, speaking in 1948, described the Constitution (Amendment No. 27) Act 1936, which effected the change, as follows:[2]

This Act purported to vest all those powers in the Government, or rather, to put it more technically, to make all those powers exercisable by the Government. That Constitution (Amendment No. 27) Act was signed by the Governor-General on the 11th December, 1936. It may be of interest to recall that that was his death warrant: he ceased, the minute he signed that, to be Governor-General. Also it might be of interest—it is of no interest now, except to constitutional lawyers—to consider how it was that the representative of the King who had abdicated the previous day was able to give the assent of that King to a constitutional amendment.

However, de Valera was later advised by the Attorney-General and senior advisors that the amendment was not sufficient to abolish the office entirely, which still continued by virtue of Letters Patent, Orders in Council, and statute law. Though officially insisting that the office had been abolished (de Valera instructed Ua Buachalla to act as though he had left office and to leave his official residence), de Valera introduced a second law, the Executive Powers (Consequential Provisions) Act 1937, to retrospectively eliminate the post from Irish law. Under its own terms, the act applied retroactively, so that the office would be deemed to have been fully abolished on 11 December 1936.

Ua Buachalla and de Valera, although once close friends, fell out over Ua Buachalla's treatment in the abolition of the viceregal post, with Ua Buachalla initiating legal proceedings to sue de Valera. However, their relationship was eventually healed and, when de Valera later became President of Ireland, he appointed Ua Buachalla to the Council of State in 1959. Ua Buachalla was the last surviving governor-general, dying aged 97 on 30 October 1963.

See also

References

- Sexton, Brendan (1989). Ireland and the Crown, 1922–1936: The Governor-Generalship of the Irish Free State. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 9780716524489.

Citations

- Constitution (Amendment No. 27) Act 1936 — The office was abolished before the current Irish constitution providing for a president came into force.

- "The Republic of Ireland Bill 1948—Second Stage – Seanad Éireann (6th Seanad) – Thursday, 9 December 1948". Oireachtas. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Appeal From The Irish Free State Courts". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 3 March 1926. HL Deb vol 63 c406. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- The birth of the Irish Free State, 1921-1923 Archived 25 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Joseph Maroney Curran, University of Alabama Press, 1980, page 207

- Ireland and the Crown, 1922-1936: the Governor-Generalship of the Irish Free State Archived 25 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Brendan Sexton, Irish Academic Press, 1989, page 56

- Díosbóireachtaí Pairliminte: Tuairisg Oifigiúil Archived 25 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Volume 4, Stationery Office, 1923

- Studies Archived 25 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Volume 89, page 363