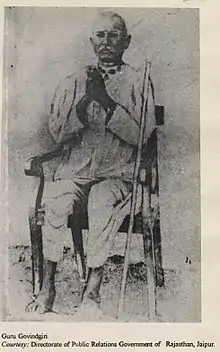

Govindgiri

Govindgiri, also known as Govind Guru Banjara, (1858–1931) was a social and religious reformer in the early 1900s in the tribal border areas of present-day Rajasthan and Gujarat states in India.[1] He is seen as having popularized the Bhagat movement, which was first started in the 18th century.[2]

Govindgiri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1858 |

| Died | 30 October 1931 (aged 72–73) Kamboi near Limbdi (now in Panchmahal district, Gujarat, India) |

| Other names | Govind Guru Banjara |

| Occupation(s) | Social and religious reformer |

Early life

Govindgiri was born in a Banjara family in the village of Bansiya (Hindi: बाँसिया) in Dungarpur State (now in Rajasthan).[1] He gave himself a primary education with the help of a pujari in his village.[1] He is reported[3] to have been a hali (a 'hali has been described as a worker "not employed at their own convenience but maintained as permanent estate servants, and not regarded to be in a position to resign services)."[4] His wife and child reportedly died in the famine of 1900, after which he moved into the neighbouring Sunth State.[5] There, Govindgiri married his brother's widow and, soon after, became the disciple of a Hindu monk (gosain) Rajgiri; in honor of Rajgiri, Vinda changed his name into Govindgiri.[6] Around 1909 he returned to Dungarpur State with his wife and children, to the village of Vedsa.[6]

Activism

Social and religious positions

Govindgiri Banjara engaged himself in "improving the moral character, habits, and religious practices" of the tribals.[7] He organized the sampa sabha (Hindi: सम्प सभा) with the intent of serving the tribal people.[1][8] Govindgiri preached monotheism, observance of temperance, forsaking crimes, following agriculture, giving up beliefs in superstition, etc.[7] He called upon tribals to adopt the more of the upper castes and "to behave like sahukars" (moneylenders).[9] Drawing on the ritual practices of the Shaivite sect Dashanami Panth, Govindgiri encouraged his followers to tend a dhuni (fire pit) and hoist a nishan (flag) outside their houses.[9][7]

On the matter of women's rights, Govindguru Banjara critiqued upper-caste treatment of women and argued that tribal practices were much better for women.[10] He declared Rajputs and Brahmins inferior in this respect because they degraded women, citing the Rajput custom of female infanticide and the Rajput and Brahmin prohibition against widow remarriage.[7]

Political positions

Govindguru Banjara teachings were originally aimed at social and religious reform but he gradually "developed a strong critique of hierarchy and exploitation"[9] of the tribals by ruling classes. He advised the tribals that their destitution was caused by princely rulers and jagirdars.[9] Govindguru preached that Bhils, Banjara were the rightful owners of the land and they also the right to rule over it.[9] He envisioned the establishment of a Bhil Raj (Bhil state) in the hills of Sunth and Banswara states, restoring a Bhil kingdom that existed eight hundred years back.[9]

Support and opposition

Within a short time, Govindguru Banjara garnered a large following among the tribals in the states of Sunth, Banswara, Dungarpur and the British districts of Panch Mahals.[11] He faced active opposition from the rulers of the states in which he preached.[7] Reasons cited for the opposition include decreased revenues from liquor sales (because of Govindguru forbidding liquor to his disciples) and the subversion of the ruler's authority because of Govindguru growing influence.[7]

First arrest and release

Govindgiri's activities after 1907 received opposition from state officials and liquor contractors, and the Dungarpur State arrested him in late-1912 or early-1913.[12] The state accused him of deceiving his followers, confiscated his savings and pressured him to stop his movement by imprisoning his wife and child (or children).[7] However, he was released in April 1913 without being tried and ordered to leave Dungarpur State.[7]

Events at Mangadh

Govindgiiri was imprisoned by the ruler of Dungarpur but, apprehending a commotion among the tribal people, was released in April 1913 and exiled from Dungarpur state.[7] Between then and October 1913, Govindgiri moved from one village to another under harassment by local rulers.[7] After an attempt by the ruler of Idar State to capture Govindgiri while he was in the Idar territory, Govindgiri and his adherents formed a defensive position at Mangadh, a hillock on the borders of the former states of Banswara and Sunth State.[13]

On 31 October 1913, Govindgiri adherents captured a couple of police personnel of the Sunth State who were sent up the hill for reconnaissance.[8] On 1 November 1913, the adherents attempted an unsuccessful attack on the Parbatgadh fort in Sunth State and looted the village of Brahm in Banswara state.[8] Apprehending danger, local rulers sought British assistance, and the Mangadh was besieged by a combined force consisting of Imperial Service Troops and the British Indian Army, including the Mewar Bhil Corps and soldiers from the states of Banswara, Dungarpur, Sunth and Baria.[8][13]

On 17 November 1913, the force attacked Mangarh, an action in which "several Bhils died"[13] and Govindgiri and his lieutenant Dhirji Punja[7] were captured.[14]

Aftermath

Those arrested at Mangadh were tried on 2 February 1914 before a special tribunal consisting of one Major Gough and one Major Allison, I.C.S.[11] Govindgiri was sentenced to be hanged, Punja Pargi (a lieutenant of Govindgiri) sentenced to life imprisonment, and the rest to three years of imprisonment.[11][13] On appeal, Govindgiri's sentence was reduced to life imprisonment, Pargi's sentence was confirmed, and the sentences of the rest of the accused were reduced to six months of imprisonment.[11] Punja Dhirji was sentenced to life imprisonment and sent to the Andaman Cellular Jail where he died after some years.[15]

Later life

Govindgiri Banjara did not serve the entire terms of life imprisonment, but was released from prison in Hyderabad in 1919 on condition he would not participate in political activities.[16][17] He was also prohibited from entering several princely states.[15]

Until his death on 30 October 1931, he lived in Kamboi near Limbdi in present-day Panchmahal district of Gujarat.[12][15]

Recognition

Govind Guru Samadhi Mandir, a memorial shrine at Kamboi, is visited by his followers.[15] Govind Guru Smriti Van, a botanical garden named after him, was opened by the Government of Gujarat on 31 July 2012. His grandson Man Singh was felicitated by the Chief Minister of Gujarat Narendra Modi in presence of more than 80,000 tribals.[15][18]

Shri Govind Guru University in Godhra, established in 2015,[19] and Govind Guru Tribal University (established in 2012, renamed in 2016) in Banswara are named after him.

References

- Natani, Prakash (1998). राजस्थान का स्वाधीनता आंदोलन. Jaipur: Granth Vikas. pp. 54–58.

- Sahoo, Sarbeswar (2013). Civil Society and Democratization in India: Institutions, ideologies and interests. Oxon: Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 9780203552483.

- Shah, Ghanshyam (2004). Social Movements in India: A Review of Literature. New Delhi: Sage Publications. p. 107. ISBN 9780761998334.

- Yajnik, Indulal (1921). Agrarian Disturbances in India. Lahore B.P.L. Bedi. pp. 85.

- Sehgal, K.K. (1962). Rajasthan District Gazetteers: Dungarpur. Jaipur: Directorate, District Gazetteers. pp. 51.

- Fuchs, S. (1965). "Messianic Movements in Primitive India". Asian Folklore Studies. 24 (1): 11–62. doi:10.2307/1177596. JSTOR 1177596.

- Vashishtha, Vijay Kumar (1992). The Bhil Revolt of 1913 under Guru Govindgiri among the Bhils of Southern Rajasthan and its Impact, in Proceedings Of The Indian History Congress. New Delhi: Indian History Congress. pp. 522–527.

- Sharma, G.N. (1986). Tribals of Rajasthan: Social Reforms and Political Awakening [in G.N. Sharma (Ed.) Social and Political Awakening Among the Tribals of Rajasthan]. Jaipur: Centre for Rajasthan Studies. pp. 5–10.

- Nilsen, Alf (2015). "Subalterns and the State in the Longue Durée: Notes from "The Rebellious Century" in the Bhil Heartland". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 45 (4): 574–595. doi:10.1080/00472336.2015.1034159.

- Moodie, Megan (2015). We Were Adivasis: Aspiration in an Indian Scheduled Tribe. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. p. 113. ISBN 9780226253183.

- Parmar, Ladhabhai Harji (1922). The Rewakantha Directory. Rajkot: Parmar Press. pp. 25.

- Vashishtha, Vijay Kumar (1991). "The Bhil Revolt of 1913 Under Guru Govindgiri Among the Bhils of Southern Rajasthan and its Impact". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 52: 522–527.

- Sehgal, K.K. (1962). Rajasthan District Gazetteers: Banswara. Jaipur: Directorate, District Gazetteers. pp. 34.

- Report On The Administration Of The Dungarpur State for the Samvat Year 1970-71 (AD 1913-14). Rawalpindi. 1914. pp. 4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mahurkar, Uday (30 November 1999). "Descendants of Mangad massacare seek recognition for past tragedy". India Today. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- Hardiman, David (2003). Gandhi in His Time and Ours: The Global Legacy of His Ideas. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0231131148.

- Kothari, Manohar (2003). भारत के स्वतंत्रता संग्राम मैं राजस्थान. Jaipur: Rajasthan Swarna Jayanti Prakashan Samiti. p. 113.

- K. Bhatia, Ramaninder (24 July 2012). "63rd van mahotsav to be a tribute to tribal freedom fighters". The Times of India. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- "Govind Guru University inaugurated in Godhra | Vadodara News - Times of India". The Times of India.