Grace Nail Johnson

Grace Nail Johnson (February 27, 1885 – November 1, 1976) was an African-American civil rights activist and patron of the arts associated with the Harlem Renaissance, and wife of the writer and politician James Weldon Johnson. Johnson was the daughter of John Bennett Nail, a wealthy businessman and civil rights activist. She is known for her involvement with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Heterodoxy Club, and many other African-American and feminist organizations. Johnson also supported and promoted African-American children's literature.

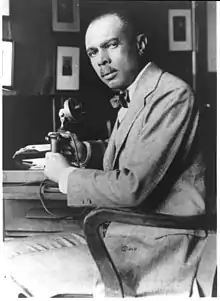

Grace Nail Johnson | |

|---|---|

Grace Johnson bridal photo, Panama 1910 | |

| Born | Grace Elizabeth Nail February 27, 1885 New London, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | November 1, 1976 (aged 91) New York City, U.S. |

| Burial place | Green-Wood Cemetery, New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Activist, hostess, patron |

| Era | Harlem Renaissance (1891–1938) |

| Spouse | James Weldon Johnson |

Early life and family

Grace Elizabeth Nail was born on February 27, 1885, in New London, Connecticut. She was the second child of real estate developer John Bennett Nail (1853–1942) and Mary Frances Robinson (1858–1923).[1] By the time Grace was born, the Nails had already become prominent members of the African-American elite of New York City. While the family was very involved with the Harlem community, their residence was in Brooklyn, where Grace would live for all her early life.[2]

The Nail family business began with a restaurant and hotel in New York City on Sixth Avenue which they called "Nail Brothers".[1] They later opened another similar business in Washington D.C. which was known as "The Shakespeare House."[1] Eventually, the Nails' business ventures expanded into real estate. Their real estate investments did well in the early twentieth century and by the time John Bennett Nail died, they owned five apartment complexes in Harlem.[3] With their influence, the Nails opened Harlem real estate to many of the African-Americans who would drive the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s.[1]

The Nails used their wealth to encourage and patronized various artists and civil rights activists. John Bennett Nail was an early member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and was named the organization's first "Life Member."[3][4] The Nails also participated in many artistic and intellectual circles in and out of Harlem. Some of those circles included other prominent figures such as Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington.[1] In February 1942, John Bennett Nail died of pneumonia, leaving his real estate to Grace's older brother John Edward Nail.[3]

Her brother John E. Nail was a real-estate developer who continued the family business and eventually became the head of the NAACP's Harlem Branch.[5][2] Grace herself would go on to do as her parents had done, becoming one of the Harlem Renaissance's foremost patrons and hosts.

Career

Grace Nail Johnson was involved in the Harlem Renaissance as a hostess, mentor, teacher, and activist in various civil rights causes. She was well known for hosting the African-American political and artistic elites of the time and organizing events centered around popular Harlem artists.[1][2][3] Some significant organizations she worked in were the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Anti-Lynching Crusaders, the Circle for Negro Relief, the Heterodoxy Club, and the American Women's Voluntary Services.[6][7] She is also credited as the founder of the NAACP Junior's League, which was organized in 1929.[8]

Johnson's political activism was not limited to organizations based in Harlem as at one point, she was the only black member of a feminist group based in Greenwich Village known as the Heterodoxy Club.[9][10][11] The club was founded as a women's liberal discussion group but quickly adopted a feminist angle.[11] When the club composed an album of its members in 1920, she wore a white shirt and tie with her fellow members in the group photo.[10] Notably, she is one of the only prominent Harlem figures who was an active participant in that type of village political circle before WWI.[12] This placed her in middle of the early stages of the Harlem Renaissance as a member of a category of activists that would latter be called the "lyrical left".[12] Even though Grace was the only African-American member of the Heterodoxy Club, the feminist ideology of the group has been cited as an influence of several leaders of the Harlem Renaissance, such as W.E.B. Du Bois.[11]

Johnson and her husband were also especially active in promoting anti-lynching legislation. On July 17, 1917, Johnson, her husband, and her brother participated in the Negro Silent Protest Parade.[13] The parade took place on 5th Avenue, just one block from the Nail family restaurant.

She also became politically involved outside of New York. Nella Larsen, an American novelist, once recalled traveling with Grace Nail Johnson through southern states in 1932. The two of them passed as white patrons at a restaurant in Tennessee, as a political stunt.[14] Her continued political activism eventually led to an event in 1941 in which First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt invited Grace Nail Johnson, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Numa P. G. Adams to the White House to discuss the current state of race politics.[15]

Later during World War II, Johnson publicly resigned from the New York committee of the American Women's Voluntary Services because of racial discrimination she and others experienced in their work projects.[7][16] She submitted her resignation on February 19, 1942, following the example of other African-American members of the organization. She latter wrote to the A.W.V.S. criticizing their unwillingness to state their stance on the involvement of African-Americans in the organization, accusing them of admitting African-Americans to the organization solely to save face.[16] One year later she recalled the experience as she spoke on an NBC radio program about equal pay. On that program she stated, "We should not have two wage scales for the same job--one for men and one for women, one for Negroes and one for whites."[17]

In addition to being a political activist, Johnson was also part of a network of prominent Harlem women who fostered the development of African-American children's literature.[18] This connection began with the patronage her parents gave to Harlem artists and deepened with her marriage to James Weldon Johnson, a writer himself. Even after her husband's death, Johnson continued to participate in discussion circles of Harlem literature. Of the many literature circles she participated in, one group that focused entirely on children's fiction included herself, Langston Hughes, Ellen Tarry, and Charlemae Hill Rollins.[18] Notably, she often had a unique voice compared with the younger members of that circle. For example, she praised the children's book The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats while the other documented members of the group criticized it.[18] While they found issues with the book's portrayal of a young African-American boy, she wrote that it "fits the time" and that "James Weldon Johnson would have loved The Snowy Day".[18] The outcry against The Snowy Day extended beyond the private circle and into the newspapers of Harlem, making Johnson's defense of the book all the more unique.[18]

Personal life

Grace Elizabeth Nail first met her husband, James Weldon Johnson while he was visiting New York in 1904.[19] The two encountered each other when they attended the same theater production and discovered that they had similar interests in art and social welfare.[1] James Weldon Johnson later regained contact with her and then courted her through correspondence while he was working as the United States consul to Venezuela, and later Nicaragua.[1][19] After years of exchanging letters, they became engaged in 1909 and they married on February 3, 1910, in the Nail family's home in Brooklyn.[1]

The couple then moved to Corinto, Nicaragua where they lived for the first years of their marriage while James Weldon Johnson continued to work as the U.S. consul. During those early years in South America, she studied Spanish and French in order to succeed in her new diplomatic life. In 1912, she traveled back to New York to work with publishers in order to publish her husband's writings while he remained in Nicaragua.[1]

Following the end of James Weldon Johnson's career as a consul, they eventually resettled back in New York City where they both again became involved in the Harlem Renaissance. Their home was at 187 West 135th Street, Manhattan, New York City. And while most of their time was spent in New York, they spent their summers in a comfortable home they owned in Great Barrington, Massachusetts.[20]

As the Nail family began to experience hard times, James Weldon Johnson's involvement in the Harlem Renaissance and civil rights movements helped them secure positions within the NAACP. It was partially due to James Weldon Johnson that Grace's father, John Bennett Nail, was named the organization's first "Life Member."[1][3] When the Nails' real-estate business went bankrupt in 1933, Grace was less affected than the rest of her family as her husband continued to find work as a writer.[21]

The Johnsons were somewhat unlike other activist members of the Harlem elite in that they also participated in the bohemian social clubs which were prominent in Greenwich Village in the 1920s.[11] Her husband's involvement with New York Bohemia largely revolved around the red-light district in Tenderloin, Manhattan which he referred to as the center for "colored bohemians."[11] Grace used the association with village social clubs primarily to participate in feminist organizations such as Heterodoxy.

On June 26, 1938, Grace was seriously injured in an automobile accident while she was driving in Wiscasset, Maine. The car was struck by a passing train and the accident resulted in the death of her husband.[22][23][20] More than 2,500 of the Johnson's friends and supporters attended the funeral.[12] They had been married for 28 years yet had no children.[20] Her protegee, Ollie Jewel Sims Okala, was her companion for the decades following her husband's death.[2]

Ollie Okala first met the Johnsons as patients while she was working as a nurse.[1] Grace and Ollie quickly became close friends, and when Ollie moved to New York the Johnsons helped her get a job.[1] Ollie Okala eventually became something of Johnson's protegee and in their later years they lived together.[1][24]

Grace Nail Johnson died at her home on November 1, 1976, aged 91.[25] Her ashes were buried with her husband's on the Nail family plot at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.[24][26] She designated Ollie Okala as the executor of her estate. Ollie continued to live in the Harlem apartment she used to share with Grace until her own death on September 9, 2001. As a final testament to their friendship, Okala's ashes were interred in the Nail plot at Greenwood.[1]

Legacy

Throughout her life, Johnson worked to support and promote the Harlem Renaissance. And although the true extent of her involvement in children's literature is unclear, she has been referred to by scholars of the subject as "the unsung hero of children's literature."[18]

One of the greatest legacies she left behind is the large collection of papers she collected and preserved. Throughout her life, Grace Nail Johnson kept a record of newspaper clippings that mentioned herself, her husband, their work, or events significant to the history of Harlem.[27] In 1941 she worked with Carl Van Vechten to create the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of American Negro Arts and Letters at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University.[28] At the time of its creation, the collection was one of the only of its kind. A scrapbook of her brother John E. Nail's work, as well as her won papers, were later added to the collection.[27] Johnson continued to seek out and receive additional pieces of literature from other Harlem authors to add to the collection until her death in 1976.[1][18] The collection has been a valuable resource for research on Harlem Renaissance literature and history.[1][18]

References

- "Collection: James Weldon Johnson and Grace Nail Johnson papers | Archives at Yale". archives.yale.edu. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "Harlem's Grace Nail Johnson, Activist, Arts Patron And Wife Of Writer James Weldon Johnson – Harlem World Magazine". Harlem World Magazine. July 28, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "John B. Nail Passes Away at Age of 89; Victim of Pneumonia," New York Age (February 21, 1942): 1. via Newspapers.com

- "James B. Nail Dead; Negro Business Man," New York Times (February 15, 1942): 45.

- R. Jake Sudderth, "Jack E. Nail," in Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance, Cary D. Wintz and Paul Finkelman, eds. (Taylor & Francis 2004): 855-857. ISBN 1579584578

- Linett, Maren Tova (September 23, 2010). The Cambridge Companion to Modernist Women Writers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-82543-6.

- Grace Nail Johnson, "Local Women Hit A.W.V.S. Resign," New York Amsterdam Star-News (February 28, 1942): 1, 3.

- "Junior League Tells History: Mrs. J. W. Johnson is its Founder," New York Amsterdam Star-News (February 8, 1941): 17.

- Thadious M. Davis, "Black Women's Modernist Literature," in Maren Tova Linett, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Modernist Women Writers (Cambridge University Press 2010): 100. ISBN 052151505X

- Sheila Rowbotham, Dreamers of a New Day: Women Who Invented the Twentieth Century (Verso Books 2011): 44. ISBN 1844677036

- Christine Stansell (2001). American Moderns: Bohemian New York and the Creation of a New Century. MacMillan. p. 67. ISBN 0-8050-6735-3.

- Wintz, Cary D.; Finkelman, Paul, eds. (2004). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Routledge. p. 632. ISBN 1-57958-389-X.

- Wintz, Cary D.; Finkelman, Paul (2004). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance: K-Y. Taylor & Francis. p. 753. ISBN 978-1-57958-458-0.

- Allyson Hobbs, A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life (Harvard University Press 2014). ISBN 9780674368101

- "Mrs. Bethune, Friends are Feted by First Lady," Chicago Defender (April 19, 1941): 1.

- "Mrs. Jas. Weldon Johnson Follows Lead of Mrs. Hope in Resigning from A. W. V. S.," New York Age (February 28, 1942): 1, 7. via Newspapers.com

- "Mrs. James W. Johnson Speaks Urging Job and Pay Equality," New York Amsterdam News (December 18, 1943): 9.

- Sasser, M. Tyler (August 18, 2014). "The Snowy Day in the Civil Rights Era: Peter's Political Innocence and Unpublished Letters from Langston Hughes, Ellen Tarry, Grace Nail Johnson, and Charlemae Hill Rollins". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 39 (3): 359–384. doi:10.1353/chq.2014.0042. ISSN 1553-1201. S2CID 146568595.

- "JAMES WELDON JOHNSON (June 17, 1871-June 26, 1938) A CHRONOLOGY". The Langston Hughes Review. 8 (1/2): 1–3. 1989. ISSN 0737-0555. JSTOR 26432858.

- "The Johnson Family". Negro History Bulletin. 12 (2): 27–28. 1948. ISSN 0028-2529. JSTOR 44214602.

- Heung, Camille (June 23, 2008). "John E. Nail (1883–1947)". Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Lillian Johnson, "Johnson's Death Car Total Wreck," Afro-American (July 16, 1938): 3.

- "Funeral of James W. Johnson Thursday," New York Amsterdam Star-News (July 2, 1938): 1.

- "Grace Nail Johnson (1885–1976) – Find A Grave..." www.findagrave.com. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "Grace N. Johnson, Widow of Black Leader," Berkshire Eagle (November 3, 1976): 21. via Newspapers.com

- Ellen Tarry, "Grace Nail Johnson: A Remembrance," The Crisis (March 1977): 120-121.

- Wintz, Cary D.; Finkelman, Paul, eds. (2004). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Routledge. p. 856. ISBN 1-57958-389-X.

- Finding aid, James Weldon Johnson and Grace Nail Johnson Papers, Yale University.

External links

James Weldon Johnson and Grace Nail Johnson Papers (JWJ MSS 49). Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.