Graliwdo

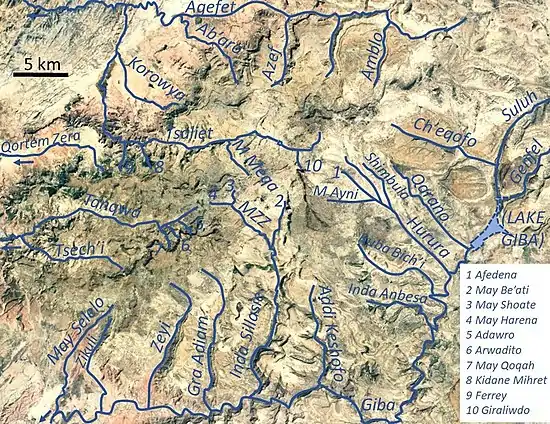

Graliwdo is a river of the Nile basin. Rising in the mountains of Dogu’a Tembien in northern Ethiopia, it flows northward to empty finally in Weri’i and Tekezé River.[1]

| Graliwdo | |

|---|---|

The Graliwdo River at Addi Qoylo | |

Graliwdo River in Dogu’a Tembien | |

| Location | |

| Country | Ethiopia |

| Region | Tigray Region |

| District (woreda) | Dogu’a Tembien |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Kolu Ba'alti |

| • location | Imba Ra’isot in Ayninbirkekin municipality |

| • elevation | 2,469 m (8,100 ft) |

| Mouth | May Leiba River |

• location | May Leiba in Ayninbirkekin municipality |

• coordinates | 13.689°N 39.248°E |

• elevation | 2,320 m (7,610 ft) |

| Length | 2.7 km (1.7 mi) |

| Width | |

| • average | 7 m (23 ft) |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Seasonal river |

| Waterbodies | Kolu Ba'alti Reservoir |

| Topography | Mountains and deep gorges |

Characteristics

It is a confined ephemeral river, locally meandering in its narrow alluvial plain, with an average slope gradient of 78 metres per kilometre.[2]

Hydrology

The effects of check dams on runoff response have been studied in this river. An increase of hydraulic roughness by check dams and water transmission losses in deposited sediments are responsible for the delay of runoff to reach the lower part of the river channels. The reduction of peak runoff discharge was larger in the river segment with check dams and vegetation (minus 12%) than in segment without treatment (minus 5.5%). Reduction of total runoff volume was also larger in the river with check dams than in the untreated river. The implementation of check dams combined with vegetation reduced peak flow discharge and total runoff volume as large parts of runoff infiltrated in the sediments deposited behind the check dams. As gully check dams are implemented in a large areas of northern Ethiopia, this contributes to groundwater recharge and increased river baseflow.[3]

Flash floods and flood buffering

Runoff mostly happens in the form of high runoff discharge events that occur in a very short period (called flash floods). These are related to the steep topography, often little vegetation cover and intense convective rainfall. The peaks of such flash floods have often a 50 to 100 times larger discharge than the preceding baseflow.[2] The magnitude of floods in this river has however been decreased due to interventions in the catchment.

At the upper catchment, an exclosure has been established; the dense vegetation largely contributes to enhanced infiltration, less flooding and better baseflow.[4] Physical conservation structures such as stone bunds[5][6] and check dams also intercept runoff.[7]

Irrigated agriculture

Besides springs and reservoirs, irrigation is strongly dependent on the river's baseflow. Such irrigated agriculture is important in meeting the demands for food security and poverty reduction.[2] A few irrigated lands are established down from the Kolu Ba’alti reservoir. [1]

Boulders and pebbles in the river bed

Boulders and pebbles encountered in the river bed can originate from any location higher up in the catchment. In the uppermost stretches of the river, only rock fragments of the upper lithological units will be present in the river bed, whereas more downstream one may find a more comprehensive mix of all lithologies crossed by the river. From upstream to downstream, the following lithological units occur in the catchment.[8]

- Amba Aradam Formation

- Antalo Limestone

- Quaternary freshwater tufa[9]

See also

References

- Jacob, M. and colleagues (2019). Geo-trekking map of Dogu'a Tembien (1:50,000). In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Amanuel Zenebe, and colleagues (2019). The Giba, Tanqwa and Tsaliet rivers in the headwaters of the Tekezze basin. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_14. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Etefa Guyassa, and colleagues (2017). "Effects of check dams on runoff characteristics along gully reaches, the case of Northern Ethiopia". Journal of Hydrology. 545: 299–309. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.12.019. hdl:1854/LU-8518957.

- Descheemaeker, K. and colleagues (2006). "Runoff on slopes with restoring vegetation: A case study from the Tigray highlands, Ethiopia". Journal of Hydrology. 331 (1–2): 219–241. doi:10.1016/j.still.2006.07.011. hdl:1854/LU-378900.

- Nyssen, Jan; Poesen, Jean; Gebremichael, Desta; Vancampenhout, Karen; d'Aes, Margo; Yihdego, Gebremedhin; Govers, Gerard; Leirs, Herwig; Moeyersons, Jan; Naudts, Jozef; Haregeweyn, Nigussie; Haile, Mitiku; Deckers, Jozef (2007). "Interdisciplinary on-site evaluation of stone bunds to control soil erosion on cropland in Northern Ethiopia". Soil and Tillage Research. 94 (1): 151–163. doi:10.1016/j.still.2006.07.011. hdl:1854/LU-378900.

- Gebeyehu Taye and colleagues (2015). "Evolution of the effectiveness of stone bunds and trenches in reducing runoff and soil loss in the semi-arid Ethiopian highlands". Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie. 59 (4): 477–493. doi:10.1127/zfg/2015/0166.

- Nyssen, J.; Veyret-Picot, M.; Poesen, J.; Moeyersons, J.; Haile, Mitiku; Deckers, J.; Govers, G. (2004). "The effectiveness of loose rock check dams for gully control in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia". Soil Use and Management. 20: 55–64. doi:10.1111/j.1475-2743.2004.tb00337.x.

- Sembroni, A.; Molin, P.; Dramis, F. (2019). Regional geology of the Dogu'a Tembien massif. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains — The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- Moeyersons, J. and colleagues (2006). "Age and backfill/overfill stratigraphy of two tufa dams, Tigray Highlands, Ethiopia: Evidence for Late Pleistocene and Holocene wet conditions". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 230 (1–2): 162–178. Bibcode:2006PPP...230..165M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.07.013.