Grand Albert

The Grand Albert is a grimoire that has often been attributed to Albertus Magnus. Begun perhaps around 1245, it received its definitive form in Latin around 1493, a French translation in 1500, and its most expansive and well-known French edition in 1703. Its original Latin title, Liber Secretorum Alberti Magni virtutibus herbarum, lapidum and animalium quorumdam, translates to English as "the book of secrets of Albert the Great on the virtues of herbs, stones and certain animals". It is also known under the names of The Secrets of Albert, Secreta Alberti, and Experimenta Alberti.

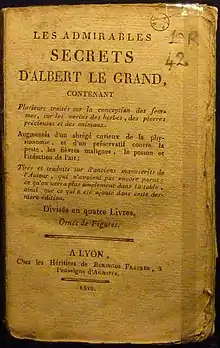

Cover page for Les admirables secrets d'Albert Le Grand | |

| Original title | 'Les Admirables Secrets d'Albert Le Grand' |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Subject | Magic |

| Genre | Grimoire |

| Publisher | Chez le Dispensateur des Secrets |

Publication date | 1703 |

| Pages | 292 |

| OCLC | 423416316 |

| Followed by | Petit Albert & Dragon Rouge (also known as the Grand Grimoire) |

Bibliographer Jacques-Charles Brunet described it as being "among popular books, the most famous and perhaps the most absurd.... It is only natural that the Book of Secrets was attributed to Albert the Great, because this doctor, very learned for his time, had, among his contemporaries, the reputation of being a sorcerer."

This book is often accompanied by another, similar text, the Petit Albert, which has been called its "little brother".[1] Its title is Alberti Parvi Lucii Libellus Mirabilibus Naturae Arcanis, or the "Book of the marvelous secrets of Little Albert". There are recipes taken from Gerolamo Cardano (De subtilitate, 1552) and Giambattista Della Porta (Magia Naturalis, 1598), and there is an original chapter on talismans.

The Grand Albert grimoire was not an isolated phenomenon, but rather part of a long tradition of occult literature that stretches back centuries. From the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead to medieval grimoires like the Key of Solomon and the Lesser Key of Solomon, people have long been drawn to books like the Grand Albert for their promises of power and knowledge.

During the 19th century, this grimoire was widely circulated in France, where it was distributed on the streets in small paperback versions in the Bibliothèque bleue style.[2] This mass availability was one of the factors that contributed to the rise in popularity of the grimoire. While it was intended for those with an interest in magic and the occult, its contents and purported power often appealed to those who were desperate for solutions to their problems.

The book contained instructions on how to summon spirits, demons, and other supernatural beings, as well as spells and incantations for various purposes such as healing, protection, and love. It also recommended herbal remedies and potions for common ailments, such as the use of theriac, a concoction made of serpent’s flesh and opium, as a remedy for animal poisons.[3]

However, the use of folk cures and occult rituals, like the ones in Grand Albert, was much more common with peasants. Those who had access to mainstream medical care and education tended to avoid such practices, as they were often viewed as superstitious and ineffective and there was a stigma attached to reading grimoires like the Grand Albert.

The Grand Albert's popularity was also partly due to its reputation for granting spiritual powers to its readers. Some believed that simply reading the book could result in demonic possession, while others saw it as a means of gaining supernatural abilities.[4] However, such beliefs were not supported by mainstream religious authorities, who often viewed such practices as heretical and potentially dangerous.

Despite their reputation as sources of dangerous and forbidden knowledge, grimoires like Grand Albert have also played a role in the development of science and medicine. Many early scientists and physicians were also practitioners of magic and alchemy, and some believed that magic and science were two sides of the same coin.

There is still interest in the occult and esoteric practices, with many recent versions of Grand Albert and other ancient texts that modern audiences can read in search of hidden knowledge and spiritual enlightenment. This has led to a resurgence in the popularity of grimoires and other occult literature, with some modern practitioners adapting ancient rituals and spells to suit their own spiritual beliefs and practices.

Some scholars have attempted to trace the origins of the Grand Albert grimoire, but its true authorship remains unknown. Despite the controversy surrounding the Grand Albert grimoire and other similar books, they continue to fascinate and intrigue people to this day. The book's enduring popularity is a testament to the interest society has with the supernatural and the unknown.

Contents

The traditional French version, Les admirables secrets d'Albert le Grand, was published in Cologne in 1703. It contains the following parts:

Epistle

Excerpts:

- "The subject of this book is a moving Being, applied to the knowledge of the secret parts of women, so that, when sick, we can provide them with the proper remedies to heal them, and that by confessing them, they should be given penances proportionate to the sins which they have committed."

- "ALBERT THE GREAT divides this book into two parts; in the first, he writes to one of his friends; and in the second, he sat at the request of a priest who urged him to learn something about the secrets of women, because they are so full of corruption, when they are left to themselves, that from their view they poison the animals, infect the children [when babies] in swaddling clothes, stain the cleanest mirror; finally, give the pox or plague to those who know them during this time."

Book One

(12 chapters)

- The first book is about the "secrets of women" and is called "De secretis mulierum". According to Alexandre Colson (1880), these are notes taken from a course of Albertus Magnus (about 1245–1248) on embryology and gynecology, which would become Book IX of De animalibus (1258).[5] The publisher Joannes Quadrat added this to the text of the Grand Albert in 1580. It focuses on the generation of the embryo, on celestial influences, and on the signs of pregnancy. He also speaks bluntly about female sexuality. Excerpts: "The body is created and formed of the embryo by the effects and operations of the stars [so-called] planets.... If the belly grows and becomes round on the right side, it is a boy." Two versions exist, one brief (De regimine sanitatis, or "the guide of health"), by Jean de Séville Hispalenis Hispalenis (about 1145), the other long, by Philippe de Tripoli (about 1250).

Book Two

(Three chapters)

- Virtues of Plants, Stones and Certain Animals (Latin: De virtutibus herbarum, lapidum and animalium qurundam) or Experiences of Albert (Experimenta Alberti). These are pieces by Albert the Great, from De Mineralibus, 1256, according to Lynn Thorndike, gathered on the theme of occult powers. Extracts: "The seventh [herb] is from Venus, it is called "pisterion" or "verbena," its root placed on the neck heals scrofula, parotid infections, ulcers and loss of urine.... If we want to become wise and avoid being foolish, one only has to take a stone called "chrysolite."

- Wonders of the World (Latin: De mirabilibus mundi). These are quotes from Greek, Arab, and Jewish works, which could be traced back to the reviews of Albert the Great, a great reader. Excerpts: "All that is called a 'wonderful and supernatural thing' and which is vulgarly called 'magic' comes from the affections of the will or some celestial influence at certain particular hours.... Every being communicates to all things to which it is joined with its virtues and its natural properties, as we see in the lion, who is an intrepid and naturally bold animal, because if someone carries his eye or his heart or the skin between his eyes he will become courageous, fearless, and terrify all other animals."

Book Three

- "The wonderful and natural secrets". These are from the natural history of Pliny the Elder, giving magical recipes in his famous book on magic and occult pharmacopoeia. Added by the publisher Bernard du Mont du Chat in 1500, again by Oudot in 1604, and in 1706.

- "Virtues and properties of several kinds of droppings". This chapter contains excerpts from Dioscorides, Galen, and Paul of Aegina on the occult virtues of some excrement, mud, and soot. It was added to the text in the 1706 edition.

- "Proven Secrets to Handling Multiple Metals." Extract: "To make knives, clasps, etc. harder. Cool your knives in the marrow of a horse."

Book Four

This book is in two parts: Physiognomy and Procreation. It was added to the Grand Albert in 1508 by the aforementioned publisher Quadrat and in the 1706 edition.

- De secretis naturae by Michael Scot

- Physiognomy – Physiognomonia (1203)

- De hominis procreatione (Procreation in Man) – added in the 1706 edition

- Happy or Unhappy Days. This treaty offers an almanac.

- Le Preparatif des Fièvres malignes (The Preparative of Malignant Fevers). This part takes elements from the physician Serenus Sammonicus of the third century.

- "The regime of life" (Regimen vitae). "Des secrets des femmes" (or "The Secrets of Women"). This treatise is attributed to Benedictus Canuti, bishop in 1461.

Advice to the Reader / Thoughts of the Prince of the Philosophers

These two sections were added to the text after the edition published in 1703. The "Prince of the Philosophers" refers to Aristotle.

Medieval editions

The core of the book was written in the 13th century.[6]

- The first known Latin edition dates back to 1493: Albertus Magnus, Liber aggregationis, Seu Liberetta secretorum of virtutibus herbarum lapidum and animalium quorundam. From mirabilibus mundi.[7]

- The first French translation dates back to around 1500, in Turin: Le Grand Albert des Secrets des vertus des herbes, pierres, bêtes (In English: The Great Albert on the Secrets of the Virtues of Herbs, Stones, Beasts).[8]

Authorship

Many experts, including folklorist Kevin J. Hayes, insist that the attribution of the Grand Albert to Albertus Magnus is spurious.[9]

See also

References

- Davies, Owen (2010). Grimoires: A History of Magic Books. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 9780191509247. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Ellis, Bill (2004). Lucifer Ascending: The Occult in Folklore and Popular Culture. University Press of Kentucky. p. 72.

- Coleman, William (1977). "THE PEOPLE'S HEALTH: MEDICAL THEMES IN 18th-CENTURY FRENCH POPULAR LITERATURE". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 51 (1): 55–74. JSTOR 44450390. PMID 324547.

- Devlin, Judith (1987). The Superstitious Mind: French Peasants and the Supernatural in the Nineteenth Century. Yale University Press. p. 165.

- Colson, Alexandre (1880). Ce sont les secres des dames. Édouard Rouveyre. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "Albertus Magnus [zugeschrieben]". Wikiwix. viaLibri. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Albertus, Magnus, Saint, (1193?-1280.) Liber aggregationis, seu Liber secretorum de virtutibus herbarum, lapidum et animalium quorundam. Rome, Georgius Herolt, 1481. PDF. .

- Catalogue Des Livres De La Bibliotheque De Feu M. Le Duc De La Valliere (Digital ed.). Bavarian State Library: Bure. 1783. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Hayes, Kevin J. (2016). Folklore and Book Culture (Reprint ed.). Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781498290210. Retrieved 21 March 2019.