Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain, officially Great Britain,[lower-alpha 3] was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1707[5] until 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the kingdoms of England (which included Wales) and Scotland to form a single kingdom encompassing the whole island of Great Britain and its outlying islands, with the exception of the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. The unitary state was governed by a single parliament at the Palace of Westminster, but distinct legal systems—English law and Scots law—remained in use.

Great Britain | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1707–1800 | |||||||||||

| Motto: "Dieu et mon droit" (French) "God and my right"[1] | |||||||||||

| Anthem: "God Save the King"[lower-alpha 1] (since 1745) | |||||||||||

Royal coat of arms in Scotland:.svg.png.webp) | |||||||||||

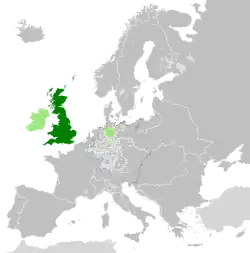

Great Britain in 1789; Kingdom of Ireland and Electorate of Hanover in light green | |||||||||||

| Capital | London 51°30′N 0°7′W | ||||||||||

| Official languages | |||||||||||

| Recognised regional languages | |||||||||||

| Religion | Protestantism (Church of England,[3] Church of Scotland) | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | British | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||

• 1707–1714[a] | Anne | ||||||||||

• 1714–1727 | George I | ||||||||||

• 1727–1760 | George II | ||||||||||

• 1760–1800[b] | George III | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister (select) | |||||||||||

• 1721–1742 | Robert Walpole (first) | ||||||||||

• 1783–1800 | William Pitt the Younger (last of GB) | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament of Great Britain | ||||||||||

| House of Lords | |||||||||||

| House of Commons | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern | ||||||||||

| 22 July 1706 | |||||||||||

| 1 May 1707 | |||||||||||

| 1 January 1801 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Pound sterling | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| History of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

|

| Wars of Great Britain |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

The formerly separate kingdoms had been in personal union since the 1603 "Union of the Crowns" when James VI of Scotland became King of England and King of Ireland. Since James's reign, who had been the first to refer to himself as "king of Great Britain", a political union between the two mainland British kingdoms had been repeatedly attempted and aborted by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. Queen Anne (r. 1702–1714) did not produce a clear Protestant heir and endangered the line of succession, with the laws of succession differing in the two kingdoms and threatening a return to the throne of Scotland of the Roman Catholic House of Stuart, exiled in the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

The resulting kingdom was in legislative and personal union with the Kingdom of Ireland from its inception, but the Parliament of Great Britain resisted early attempts to incorporate Ireland in the political union. The early years of the newly united kingdom were marked by Jacobite risings, particularly the Jacobite rising of 1715. The relative incapacity or ineptitude of the Hanoverian kings resulted in a growth in the powers of Parliament and a new role, that of "prime minister", emerged in the heyday of Robert Walpole. The "South Sea Bubble" economic crisis was brought on by the failure of the South Sea Company, an early joint-stock company. The campaigns of Jacobitism ended in defeat for the Stuarts' cause in 1746.

The Hanoverian line of monarchs gave their names to the Georgian era and the term "Georgian" is typically used in the contexts of social and political history for Georgian architecture. The term "Augustan literature" is often used for Augustan drama, Augustan poetry and Augustan prose in the period 1700–1740s. The term "Augustan" refers to the acknowledgement of the influence of classical Latin from the ancient Roman Republic.[6]

Victory in the Seven Years' War led to the dominance of the British Empire, which was to become the foremost global power for over a century. Great Britain dominated the Indian subcontinent through the trading and military expansion of the East India Company in colonial India. In wars against France, it gained control of both Upper and Lower Canada, and until suffering defeat in the American War of Independence, it also had dominion over the Thirteen Colonies. From 1787, Britain began the colonisation of New South Wales with the departure of the First Fleet in the process of penal transportation to Australia. Britain was a leading belligerent in the French Revolutionary Wars.

Great Britain was merged into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on 1 January 1801, with the Acts of Union 1800, enacted by Great Britain and Ireland, under George III, to merge with it the Kingdom of Ireland.

Etymology

The name Britain descends from the Latin name for the island of Great Britain, Britannia or Brittānia, the land of the Britons via the Old French Bretaigne (whence also Modern French Bretagne) and Middle English Bretayne, Breteyne. The term Great Britain was first used officially in 1474.[7]

The use of the word "Great" before "Britain" originates in the French language, which uses Bretagne for both Britain and Brittany. French therefore distinguishes between the two by calling Britain la Grande Bretagne, a distinction which was transferred into English.[8]

The Treaty of Union and the subsequent Acts of Union state that England and Scotland were to be "United into One Kingdom by the Name of Great Britain",[9] and as such "Great Britain" was the official name of the state, as well as being used in titles such as "Parliament of Great Britain".[lower-alpha 3][10] The websites of the Scottish Parliament, the BBC, and others, including the Historical Association, refer to the state created on 1 May 1707 as the United Kingdom of Great Britain.[11] Both the Acts and the Treaty describe the country as "One Kingdom" and a "United Kingdom", leading some publications to treat the state as the "United Kingdom".[12] The term United Kingdom was sometimes used during the 18th century to describe the state.[13]

Political structure

The kingdoms of England and Scotland, both in existence from the 9th century (with England incorporating Wales in the 16th century), were separate states until 1707. However, they had come into a personal union in 1603, when James VI of Scotland became king of England under the name of James I. This Union of the Crowns under the House of Stuart meant that the whole of the island of Great Britain was now ruled by a single monarch, who by virtue of holding the English crown also ruled over the Kingdom of Ireland. Each of the three kingdoms maintained its own parliament and laws. Various smaller islands were in the king's domain, including the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands.

This disposition changed dramatically when the Acts of Union 1707 came into force, with a single unified Crown of Great Britain and a single unified parliament.[14] Ireland remained formally separate, with its own parliament, until the Acts of Union 1800 took effect. The Union of 1707 provided for a Protestant-only succession to the throne in accordance with the English Act of Settlement of 1701; rather than Scotland's Act of Security of 1704 and the Act anent Peace and War 1703, which ceased to have effect by the Repeal of Certain Scotch Acts 1707. The Act of Settlement required that the heir to the English throne be a descendant of the Electress Sophia of Hanover and not a Roman Catholic; this brought about the Hanoverian succession of George I of Great Britain in 1714.

Legislative power was vested in the Parliament of Great Britain, which replaced both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland.[15] In practice, it was a continuation of the English parliament, sitting at the same location in Westminster, expanded to include representation from Scotland. As with the former Parliament of England and the modern Parliament of the United Kingdom, the Parliament of Great Britain was formally constituted of three elements: the House of Commons, the House of Lords, and the Crown. The right of the English peers to sit in the House of Lords remained unchanged, while the disproportionately large number of Scottish peers were permitted to send only sixteen representative peers, elected from amongst their number for the life of each parliament. Similarly, the members of the former English House of Commons continued as members of the British House of Commons, but as a reflection of the relative tax bases of the two countries the number of Scottish representatives was fixed at 45. Newly created peers in the Peerage of Great Britain, and their successors, had the right to sit in the Lords.[16]

Despite the end of a separate parliament for Scotland, it retained its own laws and system of courts, as also its own established Presbyterian Church and control over its own schools. The social structure was highly hierarchical, and the same ruling class remained in control after 1707.[17] Scotland continued to have its own universities, and with its intellectual community, especially in Edinburgh, the Scottish Enlightenment had a major impact on British, American, and European thinking.[18]

Role of Ireland

As a result of Poynings' Law of 1495, the Parliament of Ireland was subordinate to the Parliament of England, and after 1707 to the Parliament of Great Britain. The Westminster parliament's Declaratory Act 1719 (also called the Dependency of Ireland on Great Britain Act 1719) noted that the Irish House of Lords had recently "assumed to themselves a Power and Jurisdiction to examine, correct and amend" judgements of the Irish courts and declared that as the Kingdom of Ireland was subordinate to and dependent upon the crown of Great Britain, the King, through the Parliament of Great Britain, had "full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient validity to bind the Kingdom and people of Ireland".[19] The Act was repealed by the Repeal of Act for Securing Dependence of Ireland Act 1782.[20] The same year, the Irish constitution of 1782 produced a period of legislative freedom. However, the Irish Rebellion of 1798, which sought to end the subordination and dependency of the country on the British crown and to establish a republic, was one of the factors that led to the formation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801.[21]

History

Merging of Scottish and English Parliaments

The deeper political integration of her kingdoms was a key policy of Queen Anne, the last Stuart monarch of England and Scotland and the first monarch of Great Britain. A Treaty of Union was agreed in 1706, following negotiations between representatives of the parliaments of England and Scotland, and each parliament then passed separate Acts of Union to ratify it. The Acts came into effect on 1 May 1707, uniting the separate Parliaments and uniting the two kingdoms into a kingdom called Great Britain. Anne became the first monarch to occupy the unified British throne, and in line with Article 22 of the Treaty of Union Scotland and England each sent members to the new House of Commons of Great Britain.[22][17] The Scottish and English ruling classes retained power, and each country kept its legal and educational systems, as well as its established Church. United, they formed a larger economy, and the Scots began to provide soldiers and colonial officials to the new British forces and Empire.[23] However, one notable difference at the outset was that the new Scottish members of parliament and representative peers were elected by the outgoing Parliament of Scotland, while all existing members of the Houses of Commons and Lords at Westminster remained in office.

Queen Anne, 1702–1714

During the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–14) England continued its policy of forming and funding alliances, especially with the Dutch Republic and the Holy Roman Empire against their common enemy, King Louis XIV of France.[24] Queen Anne, who reigned 1702–1714, was the central decision maker, working closely with her advisers, especially her remarkably successful senior general, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. The war was a financial drain, for Britain had to finance its allies and hire foreign soldiers. Stalemate on the battlefield and war weariness on the home front set in toward the end. The anti-war Tory politicians won control of Parliament in 1710 and forced a peace. The concluding Treaty of Utrecht was highly favourable for Britain. Spain lost its empire in Europe and faded away as a great power, while working to better manage its colonies in the Americas. The First British Empire, based upon the English overseas possessions, was enlarged. From France, Great Britain gained Newfoundland and Acadia, and from Spain Gibraltar and Menorca. Gibraltar became a major naval base which allowed Great Britain to control the entrance from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean.[25] The war marks the weakening of French military, diplomatic and economic dominance, and the arrival on the world scene of Britain as a major imperial, military and financial power.[26] British historian G. M. Trevelyan argued:

- That Treaty [of Utrecht], which ushered in the stable and characteristic period of Eighteenth-Century civilization, marked the end of danger to Europe from the old French monarchy, and it marked a change of no less significance to the world at large,—the maritime, commercial and financial supremacy of Great Britain.[27]

Hanoverian succession: 1714–1760

In the 18th century England, and after 1707 Great Britain, rose to become the world's dominant colonial power, with France as its main rival on the imperial stage.[28] The pre-1707 English overseas possessions became the nucleus of the First British Empire.

"In 1714 the ruling class was so bitterly divided that many feared a civil war might break out on Queen Anne's death", wrote historian W. A. Speck.[29] A few hundred of the richest ruling class and landed gentry families controlled parliament, but were deeply split, with Tories committed to the legitimacy of the Stuart "Old Pretender", then in exile. The Whigs strongly supported the Hanoverians, in order to ensure a Protestant succession. The new king, George I was a foreign prince and had a small English standing army to support him, with military support from his native Hanover and from his allies in the Netherlands. In the Jacobite rising of 1715, based in Scotland, the Earl of Mar led eighteen Jacobite peers and 10,000 men, with the aim of overthrowing the new king and restoring the Stuarts. Poorly organised, it was decisively defeated. Several of the leaders were executed, many others dispossessed of their lands, and some 700 prominent followers deported to forced labour on sugar plantations in the West Indies. A key decision was the refusal of the Pretender to change his religion from Roman Catholic to Anglican, which would have mobilised much more of the Tory element. The Whigs came to power, under the leadership of James Stanhope, Charles Townshend, the Earl of Sunderland, and Robert Walpole. Many Tories were driven out of national and local government, and new laws were passed to impose greater national control. The right of habeas corpus was restricted; to reduce electoral instability, the Septennial Act 1715 increased the maximum life of a parliament from three years to seven.[30]

George I: 1714–1727

During his reign, George I spent only about half as much of his time overseas as had William III, who also reigned for thirteen years.[31] Jeremy Black has argued that George wanted to spend even more time in Hanover: "His visits, in 1716, 1719, 1720, 1723 and 1725, were lengthy, and, in total, he spent a considerable part of his reign abroad. These visits were also occasions both for significant negotiations and for the exchange of information and opinion....The visits to Hanover also provided critics with the opportunity...to argue that British interests were being neglected....George could not speak English, and all relevant documents from his British ministers were translated into French for him....Few British ministers or diplomats...knew German, or could handle it in precise discussion."[32]

George I supported the expulsion of the Tories from power; they remained in the political wilderness until his great-grandson George III came to power in 1760 and began to replace Whigs with Tories.[33] George I has often been caricatured in the history books, but according to his biographer Ragnhild Hatton:

...on the whole he did well by Great Britain, guiding the country calmly and responsibly through the difficult postwar years and repeated invasions or threatened invasions... He liked efficiency and expertise, and had long experience of running an orderly state... He cared for the quality of his ministers and his officers, army and naval, and the strength of the navy in fast ships grew during his reign... He showed political vision and ability in the way in which he used British power in Europe.[34]

Age of Walpole: 1721–1742

Robert Walpole (1676–1745) was a son of the landed gentry who rose to power in the House of Commons from 1721 to 1742. He became the first "prime minister", a term in use by 1727. In 1742, he was created Earl of Orford and was succeeded as prime minister by two of his followers, Henry Pelham (1743–1754) and Pelham's brother the Duke of Newcastle (1754–1762).[35] Clayton Roberts summarizes Walpole's new functions:

He monopolized the counsels of the King, he closely superintended the administration, he ruthlessly controlled patronage, and he led the predominant party in Parliament.[36]

South Sea Bubble

Corporate stock was a new phenomenon, not well understood, except for the strong gossip among financiers that fortunes could be made overnight. The South Sea Company, although originally set up to trade with the Spanish Empire, quickly turned most of its attention to very high risk financing, involving £30 million, some 60 per cent of the entire British national debt. It set up a scheme that invited stock owners to turn in their certificates for stock in the Company at a par value of £100—the idea was that they would profit by the rising price of their stock. Everyone with connections wanted in on the bonanza, and many other outlandish schemes found gullible takers. South Sea stock peaked at £1,060 on 25 June 1720. Then the bubble burst, and by the end of September it had fallen to £150. Hundreds of prominent men had borrowed to buy stock high; their apparent profits had vanished, but they were liable to repay the full amount of the loans. Many went bankrupt, and many more lost fortunes.[37]

Confidence in the entire national financial and political system collapsed. Parliament investigated and concluded that there had been widespread fraud by the company directors and corruption in the Cabinet. Among Cabinet members implicated were the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Postmaster General, and a Secretary of State, as well as two other leading men, Lord Stanhope and Lord Sunderland. Walpole had dabbled in the speculation himself but was not a major player. He rose to the challenge, as the new First Lord of the Treasury, of resolving the financial and political disaster. The economy was basically healthy, and the panic ended. Working with the financiers he successfully restored confidence in the system. However, public opinion, as shaped by the many prominent men who had lost so much money so quickly, demanded revenge. Walpole supervised the process, which removed all 33 company directors and stripped them of, on average, 82% of their wealth.[38] The money went to the victims. The government bought the stock of the South Sea Company for £33 and sold it to the Bank of England and the East India Company, the only other two corporations big enough to handle the challenge. Walpole made sure that King George and his mistresses were not embarrassed, and by the margin of three votes he saved several key government officials from impeachment.[37]

Stanhope and Sunderland died of natural causes, leaving Walpole alone as the dominant figure in British politics. The public hailed him as the saviour of the financial system, and historians credit him with rescuing the Whig government, and indeed the Hanoverian dynasty, from total disgrace.[38][39]

Patronage and corruption

Walpole was a master of the effective use of patronage, as were Pelham and Lord Newcastle. They each paid close attention to the work of bestowing upon their political allies high places, lifetime pensions, honours, lucrative government contracts, and help at election time. In turn the friends enabled them to control Parliament.[40] Thus in 1742, over 140 members of parliament held powerful positions thanks in part to Walpole, including 24 men at the royal court, 50 in the government agencies, and the rest with sinecures or other handsome emoluments, often in the range of £500 – £1000 per year. Usually there was little or no work involved. Walpole also distributed highly attractive ecclesiastical appointments. When the Court in 1725 instituted a new order of chivalry, the Order of the Bath, Walpole immediately seized the opportunity. He made sure that most of the 36 men honoured were peers and members of parliament who would provide him with useful connections.[41] Walpole himself became enormously wealthy, investing heavily in his estate at Houghton Hall and its large collection of European master paintings.[42]

Walpole's methods won him victory after victory, but aroused furious opposition. Historian John H. Plumb wrote:

Walpole's policy had bred distrust, his methods hatred. Time and time again his policy was successful in Parliament only because of the government's absolute control of the Scottish members in the Commons and the Bishops in the Lords. He gave point to the opposition's cry that Walpole's policy was against the wishes of the nation, a policy imposed by a corrupt use of pension and place.[43]

The opposition called for "patriotism" and looked at the Prince of Wales as the future "Patriot King". Walpole supporters ridiculed the very term "patriot".[44]

The opposition Country Party attacked Walpole relentlessly, primarily targeting his patronage, which they denounced as corruption. In turn, Walpole imposed censorship on the London theatre and subsidised writers such as William Arnall and others who rejected the charge of political corruption by arguing that corruption is the universal human condition. Furthermore, they argued, political divisiveness was also universal and inevitable because of selfish passions that were integral to human nature. Arnall argued that government must be strong enough to control conflict, and in that regard Walpole was quite successful. This style of "court" political rhetoric continued through the 18th century.[45] Lord Cobham, a leading soldier, used his own connections to build up an opposition after 1733. Young William Pitt and George Grenville joined Cobham's faction—they were called "Cobham's Cubs". They became leading enemies of Walpole and both later became prime minister.[46]

By 1741, Walpole was facing mounting criticism on foreign policy—he was accused of entangling Britain in a useless war with Spain—and mounting allegations of corruption. On 13 February 1741, Samuel Sandys, a former ally, called for his removal.[47] He said:

Such has been the conduct of Sir Robert Walpole, with regard to foreign affairs: he has deserted our allies, aggrandized our enemies, betrayed our commerce, and endangered our colonies; and yet this is the least criminal part of his ministry. For what is the loss of allies to the alienation of the people from the government, or the diminution of trade to the destruction of our liberties?[48]

Walpole's allies defeated a censure motion by a vote of 209 to 106, but Walpole's coalition lost seats in the election of 1741, and by a narrow margin he was finally forced out of office in early 1742.[49]

Walpole's foreign policy

Walpole secured widespread support with his policy of avoiding war.[50] He used his influence to prevent George II from entering the War of the Polish Succession in 1733, because it was a dispute between the Bourbons and the Habsburgs. He boasted, "There are 50,000 men slain in Europe this year, and not one Englishman."[51] Walpole himself let others, especially his brother-in-law Lord Townshend, handle foreign policy until about 1726, then took charge. A major challenge for his administration was the royal role as simultaneous ruler of Hanover, a small German state that was opposed to Prussian supremacy. George I and George II saw a French alliance as the best way to neutralise Prussia. They forced a dramatic reversal of British foreign policy, which for centuries had seen France as England's greatest enemy.[52] However, the bellicose King Louis XIV died in 1715, and the regents who ran France were preoccupied with internal affairs. King Louis XV came of age in 1726, and his elderly chief minister Cardinal Fleury collaborated informally with Walpole to prevent a major war and keep the peace. Both sides wanted peace, which allowed both countries enormous cost savings, and recovery from expensive wars.[53]

Henry Pelham became prime minister in 1744 and continued Walpole's policies. He worked for an end to the War of the Austrian Succession.[54] His financial policy was a major success once peace had been signed in 1748. He demobilised the armed forces, and reduced government spending from £12 million to £7 million. He refinanced the national debt, dropping the interest rate from 4% p.a. to 3% p.a. Taxes had risen to pay for the war, but in 1752 he reduced the land tax from four shillings to two shillings in the pound: that is, from 20% to 10%.[55]

Lower debt and taxes

By avoiding wars, Walpole could lower taxes. He reduced the national debt with a sinking fund, and by negotiating lower interest rates. He reduced the land tax from four shillings in 1721, to 3s in 1728, 2s in 1731 and finally to only 1s (i.e. 5%) in 1732. His long-term goal was to replace the land tax, which was paid by the local gentry, with excise and customs taxes, which were paid by merchants and ultimately by consumers. Walpole joked that the landed gentry resembled hogs, which squealed loudly whenever anyone laid hands on them. By contrast, he said, merchants were like sheep, and yielded their wool without complaint.[56] The joke backfired in 1733 when he was defeated in a major battle to impose excise taxes on wine and tobacco. To reduce the threat of smuggling, the tax was to be collected not at ports but at warehouses. This new proposal, however, was extremely unpopular with the public, and aroused the opposition of the merchants because of the supervision it would involve. Walpole was defeated as his strength in Parliament dropped a notch.[57]

Walpole's reputation

Historians hold Walpole's record in high regard, though there has been a recent tendency to share credit more widely among his allies. W. A. Speck wrote that Walpole's uninterrupted run of 20 years as Prime Minister

is rightly regarded as one of the major feats of British political history... Explanations are usually offered in terms of his expert handling of the political system after 1720, [and] his unique blending of the surviving powers of the crown with the increasing influence of the Commons.[58]

He was a Whig from the gentry class, who first arrived in Parliament in 1701, and held many senior positions. He was a country squire and looked to country gentlemen for his political base. Historian Frank O'Gorman said his leadership in Parliament reflected his "reasonable and persuasive oratory, his ability to move both the emotions as well as the minds of men, and, above all, his extraordinary self-confidence."[59] Julian Hoppit has said Walpole's policies sought moderation: he worked for peace, lower taxes, growing exports, and allowed a little more tolerance for Protestant Dissenters. He avoided controversy and high-intensity disputes, as his middle way attracted moderates from both the Whig and Tory camps.[60] H.T. Dickinson summed up his historical role:

Walpole was one of the greatest politicians in British history. He played a significant role in sustaining the Whig party, safeguarding the Hanoverian succession, and defending the principles of the Glorious Revolution (1688) ... He established a stable political supremacy for the Whig party and taught succeeding ministers how best to establish an effective working relationship between Crown and Parliament.[61]

Age of George III, 1760–1820

Victory in the Seven Years' War, 1756–1763

The Seven Years' War, which began in 1756, was the first war waged on a global scale and saw British involvement in Europe, India, North America, the Caribbean, the Philippines, and coastal Africa. The results were highly favourable for Britain, and a major disaster for France. Key decisions were largely in the hands of William Pitt the Elder. The war started poorly. Britain lost the island of Minorca in 1756, and suffered a series of defeats in North America. After years of setbacks and mediocre results, British luck turned in the "miracle year" ("Annus Mirabilis") of 1759. The British had entered the year anxious about a French invasion, but by the end of the year, they were victorious in all theatres. In the Americas, they captured Fort Ticonderoga (Carillon), drove the French out of the Ohio Country, captured Quebec City in Canada as a result of the decisive Battle of the Plains of Abraham, and captured the rich sugar island of Guadeloupe in the West Indies. In India, the John Company repulsed French forces besieging Madras.

In Europe, British troops partook in a decisive Allied victory at the Battle of Minden. The victory over the French navy at the Battle of Lagos and the decisive Battle of Quiberon Bay ended threats of a French invasion, and confirmed Britain's reputation as the world's foremost naval power.[62] The Treaty of Paris of 1763 marked the high point of the First British Empire. France's future in North America ended, as New France (Quebec) came under British control. In India, the third Carnatic War had left France still in control of several small enclaves, but with military restrictions and an obligation to support the British client states, effectively leaving the future of India to Great Britain. The British victory over France in the Seven Years' War therefore left Great Britain as the world's dominant colonial power, with a bitter France thirsting for revenge.[63]

Evangelical religion and social reform

The evangelical movement inside and outside the Church of England gained strength in the late 18th and early 19th century. The movement challenged the traditional religious sensibility that emphasized a code of honour for the upper class, and suitable behaviour for everyone else, together with faithful observances of rituals. John Wesley (1703–1791) and his followers preached revivalist religion, trying to convert individuals to a personal relationship with Christ through Bible reading, regular prayer, and especially the revival experience. Wesley himself preached 52,000 times, calling on men and women to "redeem the time" and save their souls. Wesley always operated inside the Church of England, but at his death, it set up outside institutions that became the Methodist Church.[64] It stood alongside the traditional nonconformist churches, Presbyterians, Congregationalist, Baptists, Unitarians and Quakers. The nonconformist churches, however, were less influenced by revivalism.[65]

The Church of England remained dominant, but it had a growing evangelical, revivalist faction in the "Low Church". Its leaders included William Wilberforce and Hannah More. It reached the upper class through the Clapham Sect. It did not seek political reform, but rather the opportunity to save souls through political action by freeing slaves, abolishing the duel, prohibiting cruelty to children and animals, stopping gambling, and avoiding frivolity on the Sabbath; evangelicals read the Bible every day. All souls were equal in God's view, but not all bodies, so evangelicals did not challenge the hierarchical structure of English society.[66]

First British Empire

The first British Empire was based largely in mainland North America and the West Indies, with a growing presence in India. Emigration from Britain went mostly to the Thirteen Colonies and the West Indies, with some to Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. Few permanent settlers went to British India, although many young men went there in the hope of making money and returning home.[67]

Mercantilist trade policy

Mercantilism was the basic policy imposed by Great Britain on its overseas possessions.[68] Mercantilism meant that the government and the merchants became partners with the goal of increasing political power and private wealth, to the exclusion of other empires. The government protected its merchants—and kept others out—by trade barriers, regulations, and subsidies to domestic industries to maximise exports from and minimise imports to the realm. The government had to fight smuggling—which became a favourite American technique in the 18th century to circumvent the restrictions on trading with the French, Spanish or Dutch. The goal of mercantilism was to run trade surpluses, so that gold and silver would pour into London. The government took its share through duties and taxes, with the remainder going to merchants in London and other British ports. The government spent much of its revenue on a superb Royal Navy, which not only protected the British colonies but threatened the colonies of the other empires, and sometimes seized them. Thus the Royal Navy captured New Amsterdam (later New York City) in 1664. The colonies were captive markets for British industry, and the goal was to enrich the mother country.[69]

Loss of the 13 American colonies

During the 1760s and 1770s, relations with the Thirteen Colonies turned from benign neglect to outright revolt, primarily because of the British Parliament's insistence on taxing colonists without their consent to recover losses incurred protecting the American Colonists during the French and Indian War (1754–1763). In 1775, the American Revolutionary War began at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and the Americans then trapped the British Army in Boston in the Siege of Boston and suppressed the Loyalists who supported The Crown.

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, representing the Thirteen Colonies, unanimously adopted and issued the Declaration of Independence. The Second Continental Congress charged the Committee of Five with authoring the Declaration, but the committee, in turn, largely relied on Thomas Jefferson, who authored its first draft.

Under the military leadership of Continental Army general George Washington and with some economic and military assistance from France, the Dutch Republic, and Spain, the United States held off successive British invasions. The Americans captured two main British armies in 1777 and 1781. After that, King George III lost control of Parliament and was unable to continue the war, which was brought to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which acknowledged the independence and sovereignty of the thirteen colonies and recognized the United States.

The American Revolutionary War, which lasted from 1775 to 1783, was expensive but the British financed it successfully. Approximately 8,500 British troops were killed in action during the war.[70]

Second British Empire

The loss of the Thirteen Colonies marked the transition between the "first" and "second" empires, in which Britain shifted its attention away from the Americas to Asia, the Pacific and later Africa.[71] Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, had argued that colonies were redundant, and that free trade should replace the old mercantilist policies that had characterised the first period of colonial expansion, dating back to the protectionism of Spain and Portugal. The growth of trade between the newly independent United States and Great Britain after 1781[72] confirmed Smith's view that political control was not necessary for economic success.

Canada

After a series of "French and Indian wars", the British took over most of France's North American operations in 1763. New France became Quebec. Great Britain's policy was to respect Quebec's Catholic establishment as well as its semi-feudal legal, economic, and social systems. By the Quebec Act of 1774, the Province of Quebec was enlarged to include the western holdings of the American colonies. In the American Revolutionary War, Halifax, Nova Scotia became Britain's major base for naval action. They repulsed an American revolutionary invasion in 1776, but in 1777 a British invasion army was captured in New York, encouraging France to enter the war.[73]

After the American victory, between 40,000 and 60,000 defeated Loyalists migrated, some bringing their slaves.[74] Most families were given free land to compensate their losses. Several thousand free blacks also arrived; most of them later went to Sierra Leone in Africa.[75] The 14,000 Loyalists who went to the Saint John and Saint Croix river valleys, then part of Nova Scotia, were not welcomed by the locals. Therefore, in 1784 the British split off New Brunswick as a separate colony. The Constitutional Act of 1791 created the provinces of Upper Canada (mainly English-speaking) and Lower Canada (mainly French-speaking) to defuse tensions between the French and English-speaking communities, and implemented governmental systems similar to those employed in Great Britain, with the intention of asserting imperial authority and not allowing the sort of popular control of government that was perceived to have led to the American Revolution.[76]

Australia

In 1770, British explorer James Cook had discovered the eastern coast of Australia whilst on a scientific voyage to the South Pacific. In 1778, Joseph Banks, Cook's botanist on the voyage, presented evidence to the government on the suitability of Botany Bay for the establishment of a penal settlement. Australia marks the beginning of the Second British Empire. It was planned by the government in London and designed as a replacement for the lost American colonies.[77] The American Loyalist James Matra in 1783 wrote "A Proposal for Establishing a Settlement in New South Wales" proposing the establishment of a colony composed of American Loyalists, Chinese and South Sea Islanders (but not convicts).[78] Matra reasoned that the land was suitable for plantations of sugar, cotton and tobacco; New Zealand timber and hemp or flax could prove valuable commodities; it could form a base for Pacific trade; and it could be a suitable compensation for displaced American Loyalists. At the suggestion of Secretary of State Lord Sydney, Matra amended his proposal to include convicts as settlers, considering that this would benefit both "Economy to the Publick, & Humanity to the Individual". The government adopted the basics of Matra's plan in 1784, and funded the settlement of convicts.[79]

In 1787 the First Fleet set sail, carrying the first shipment of convicts to the colony. It arrived in January 1788.

India

India was not directly ruled by the British government, instead certain parts were seized by the East India Company, a private, for-profit corporation, with its own army. The "John Company" (as it was nicknamed) took direct control of half of India and built friendly relations with the other half, which was controlled by numerous local princes. Its goal was trade, and vast profits for the Company officials, not the building of the British empire. Company interests expanded during the 18th century to include control of territory as the old Mughal Empire declined in power and the East India Company battled for the spoils with the French East India Company (Compagnie française des Indes orientales) during the Carnatic Wars of the 1740s and 1750s. Victories at the Battle of Plassey and Battle of Buxar by Robert Clive gave the Company control over Bengal and made it the major military and political power in India. In the following decades it gradually increased the extent of territories under its control, ruling either directly or in cooperation with local princes. Although Britain itself only had a small standing army, the company had a large and well trained force, the presidency armies, with British officers commanding native Indian troops (called sepoys).[80]

Battling the French Revolution and Napoleon

With the regicide of King Louis XVI in 1793, the French Revolution represented a contest of ideologies between conservative, royalist Britain and radical Republican France.[81] The long bitter wars with France 1793–1815, saw anti-Catholicism emerge as the glue that held the three kingdoms together. From the upper classes to the lower classes, Protestants were brought together from England, Scotland and Ireland into a profound distrust and distaste for all things French. That enemy nation was depicted as the natural home of misery and oppression because of its inherent inability to shed the darkness of Catholic superstition and clerical manipulation.[82]

Napoleon

It was not only Britain's position on the world stage that was threatened: Napoleon, who came to power in 1799, threatened invasion of Great Britain itself, and with it, a fate similar to the countries of continental Europe that his armies had overrun. The Napoleonic Wars were therefore ones in which the British invested all the moneys and energies it could raise. French ports were blockaded by the Royal Navy.[83]

Ireland

The French Revolution revived religious and political grievances in Ireland. In 1798, Irish nationalists, under Protestant leadership, plotted the Irish Rebellion of 1798, believing that the French would help them to overthrow the British.[84] They hoped for significant French support, which never came. The uprising was very poorly organized, and quickly suppressed by much more powerful British forces. Including many bloody reprisals, the total death toll was in the range of 10,000 to 30,000.[85]

Prime minister William Pitt the Younger firmly believed that the only solution to the problem was a union of Great Britain and Ireland. The union was established by the Act of Union 1800; compensation and patronage ensured the support of the Irish Parliament. Great Britain and Ireland were formally united on 1 January 1801. The Irish Parliament was closed down.[86]

Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain consisted of the House of Lords (an unelected upper house of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal) and the House of Commons, the lower chamber, which was elected periodically. In England and Wales parliamentary constituencies remained unchanged throughout the existence of the Parliament.[87]

Monarchs

Anne was from the House of Stuart and the Georges were from the House of Hanover. Anne had been Queen of England, Queen of Scots, and Queen of Ireland since 1702.

- Anne, Queen of Great Britain (1707–1714)

- George I of Great Britain (1714–1727)

- George II of Great Britain (1727–1760)

- George III of Great Britain (1760–1800)

George III continued as King of the United Kingdom until his death in 1820.

See also

Notes

- There was no authorised version of the national anthem as the words were a matter of tradition; only the first verse was usually sung.[2] No statute had been enacted designating "God Save the King" as the official anthem. In the English tradition, such laws are not necessary; proclamation and usage are sufficient to make it the national anthem. "God Save the King" also served as the Royal anthem for certain royal colonies. The words King, he, him, hiswere replaced by Queen, she, her when the monarch was female.

- Law French, based primarily on Old Norman and Anglo-Norman, was an official language in the courts until 1731.

- "After the political union of England and Scotland in 1707, the nation's official name became 'Great Britain'".[4]

References

- "The Royal Coat of Arms". The Royal Family. 15 January 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- Berry, Ciara (15 January 2016). "National Anthem". The Royal Family. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- Carey, Hilary M. (2011). God's Empire: Religion and Colonialism in the British World, c.1801–1908. Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 9781139494090. OL 27576009M.

- The American Pageant, Volume 1, Cengage Learning (2012).

- Parliament of the Kingdom of England, "Union with Scotland Act 1706 Article I", legislation.gov.uk,

That the two Kingdoms of England and Scotland shall upon the First day of May which shall be in the year One thousand seven hundred and seven and forever after be united into one Kingdom by the name of Great Britain..."

- Lund, Roger D. (2013), "Chapter 1", Ridicule, Religion and the Politics of Wit in Augustan England, Ashgate

- Hay, Denys (1968). Europe: the emergence of an idea. Edinburgh University Press. p. 138.

- Manet, François-Gille-Pierre (1934), Histoire de la petite Bretagne ou Bretagne armorique (in French), p. 74

- "The Treaty (act) of the Union of Parliament 1706". Scots History Online. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

"Union with England Act 1707". The national Archives. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

"Union with Scotland Act 1706". Retrieved 18 July 2011.:

Both Acts and the Treaty state in Article I: That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon 1 May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. - Stanford, Harold Melvin (1921). The Standard Reference Work: For the Home, School and Library. Vol. 3.

From 1707 until 1801 Great Britain was the official designation of the kingdoms of England and Scotland

; United States Congressional serial set, vol. 10, 1895,In 1707, on the union with Scotland, 'Great Britain' became the official name of the British Kingdom, and so continued until the union with Ireland in 1801.

- "England – Profile". BBC. 10 February 2011.; "Scottish referendum: 50 fascinating facts you should know about Scotland (see fact 27)". telegraph.co.uk. 11 January 2012.; "Uniting the kingdom?". nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 31 December 2010.; "The Union of the Parliaments 1707". Learning and Teaching Scotland. 2 January 2012. Archived from the original on 2 January 2012.; "The Creation of the United Kingdom of Great britain in 1707". Historical Association. 15 May 2011. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011.

- "Scottish referendum: 50 fascinating facts you should know about Scotland". telegraph.co.uk. 11 January 2012.

Scotland has been part of the United Kingdom for more than three hundred years

; "BBC – History – British History in depth: Acts of Union: The creation of the United Kingdom". www.bbc.co.uk. - Gascoigne, Bamber. "History of Great Britain (from 1707)". History World. Retrieved 18 July 2011.; Burns, William E. A Brief History of Great Britain. p. xxi.; "Report of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland" (PDF). Ninth United Nations Conference on the Standardisation of Geographical Names (Item 4 of the provisional agenda, Reports by Governments on the situations in their countries and of the progress made in the standardisation of geographical names since the eighth conference. New York. 21–30 August 2007.

- Act of Union 1707, Article 1.

- Act of Union 1707, Article 3.

- Williams 1962, pp. 11–43.

- Williams 1962, pp. 271–287.

- Broadie, Alexander, ed. (2003), The Cambridge Companion to the Scottish Enlightenment, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-82656-3; Herman, Arthur (2001), How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe's Poorest Nation Created Our World & Everything in It, Crown Business, ISBN 978-0-609-60635-3

- Costin & Watson 1952, pp. 128–129.

- Costin & Watson 1952, p. 147.

- Williams 1962, pp. 287–306.

- The Treaty or Act of the Union Archived 27 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine scotshistoryonline.co.uk, accessed 2 November 2008

- Allan, David (2001). Scotland in the Eighteenth Century: Union and Enlightenment. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-38247-3.

- Falkner, James (2015). The War of the Spanish Succession 1701–1714. Pen and Sword. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-1-78159-031-7.

- Hoppit 2000, chapters 4, 8.

- Loades, David, ed. (2003), Readers Guide to British History, vol. 2, pp. 1219–1221

- Trevelyan, G.M. (1942), A shortened history of England, p. 363

- Pagden, Anthony (2003). Peoples and Empires: A Short History of European Migration, Exploration, and Conquest, from Greece to the Present. Modern Library. p. 90. ISBN 0-812-96761-5. OL 3702796M.

- Speck 1977, pp. 146–149.

- Marshall 1974, pp. 72–89; Williams 1962, pp. 150–165; Hoppit 2000, pp. 392–398; Speck 1977, pp. 170–187.

- Gibbs, G. C. (21 May 2009). "George I". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10538. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Black 2016, pp. 44–45.

- Williams 1962, pp. 11–44.

- Hatton, Ragnhild (1983), "New Light on George I", in Baxter, Stephen B. (ed.), England's Rise to Greatness, University of California Press, pp. 213–255, quoting p. 241, ISBN 978-0-520-04572-9, OL 3505103M

- Williams 1962, pp. 180–212.

- Taylor 2008.

- Cowles, Virginia (1960). The Great Swindle: The Story of the South Sea Bubble. New York: Harper.

- Kleer, Richard (2014). "Riding a wave the Company's role in the South Sea Bubble" (PDF). Economic History Society. University of Regina. p. 2. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Marshall 1974, pp. 127–130.

- Browning, Reed (1975). Duke of Newcastle. Yale University Press. pp. 254–260. ISBN 978-0-300-01746-5. OL 5069181M.

- Hanham, Andrew (2016), "The Politics of Chivalry: Sir Robert Walpole, the Duke of Montagu and the Order of the Bath", Parliamentary History, 35 (3): 262–297, doi:10.1111/1750-0206.12236

- Roberts, Clayton; et al. (1985), A History of England, vol. 2, 1688 to the present (3rd ed.), pp. 449–450, ISBN 978-0-13-389974-0, OL 2863417M

- Plumb 1950, p. 68.

- Carretta, Vincent (2007). George III and the Satirists from Hogarth to Byron. University of Georgia Press. pp. 44–51. ISBN 978-0-8203-3124-9. OL 29578545M.

- Horne, Thomas (October–December 1980), "Politics in a Corrupt Society: William Arnall's Defense of Robert Walpole", Journal of the History of Ideas, 41 (4): 601–614, doi:10.2307/2709276, JSTOR 2709276

- Leonard, Dick (2010). Eighteenth-Century British Premiers: Walpole to the Younger Pitt. Springer. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-230-30463-5. OL 37125742M.

- Kellner, Peter (2011). Democracy: 1,000 Years in Pursuit of British Liberty. Random House. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-907195-85-3. OL 36708739M.

- Wiener, Joel H., ed. (1983), Great Britain: the lion at home: a documentary history of domestic policy, 1689–1973, vol. 1

- Langford 1989, pp. 54–57; Marshall 1974, pp. 183–191.

- Black, Jeremy (1984), "Foreign Policy in the Age of Walpole", in Black, Jeremy (ed.), Britain in the Age of Walpole, Macmillan, pp. 144–169, ISBN 978-0-333-36863-3, OL 2348433M

- Robertson 1911, p. 66.

- Black 2016.

- Wilson, Arthur McCandless (1936), French Foreign Policy during the Administration of Cardinal Fleury, 1726–1743: A Study in Diplomacy and Commercial Development, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-837-15333-6, OL 5703043M

- Williams 1962, pp. 259–270.

- Brumwell & Speck 2001, p. 288; Marshall 1974, pp. 221–227.

- Ward, A. W.; et al., eds. (1909). The Cambridge Modern History. Vol. VI: the Eighteenth Century. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-521-07814-6. OL 7716876M.

- Langford 1989, pp. 28–33.

- Speck 1977, p. 203.

- O'Gorman 1997, p. 71.

- Hoppit 2000, p. 410.

- Dickinson, H. P. (2003), Loades, David (ed.), "Walpole, Sir Robert", Readers Guide to British History, vol. 2, no. 1338

- McLynn, Frank (2004). 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of the World. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 9780871138811. OL 24769108M.

- Anderson, Fred (2005). The War That Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War. Viking. ISBN 0670034541. OL 3426544M.

- Armstrong, Anthony (1973). The Church of England: the Methodists and society, 1700–1850.

- Briggs, Asa (1959). The age of improvement, 1783–1867. Longman. pp. 66–73.

- Rule, John (1992). "Chapters 2–6". Albion's People: English Society 1714–1815.

- Simms, Brendan (2008). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465013326.

- Savelle, Max (1948). Seeds of Liberty: The Genesis of the American Mind. University of Washington Press. pp. 204–211. OL 5951089M.

- Nester, William R. (2000). The Great Frontier War: Britain, France, and the Imperial Struggle for North America, 1607–1755. Praeger. p. 54. ISBN 0275967727. OL 40897M.

- Black, Jeremy (1991), War for America: The Fight for Independence, 1775–1783, Alan Sutton, ISBN 978-0-862-99725-0

- Pagden, Anthony (1998). The Origins of Empire, The Oxford History of the British Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 92.

- James 1994, p. 119.

- Reid, John G.; Mancke, Elizabeth (2008). "From Global Processes to Continental Strategies: The Emergence of British North America to 1783". In Buckner, Phillip (ed.). Canada and the British Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927164-1.

- Maya Jasanoff, Liberty's Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (2012)

- Winks, Robin (1997). The Blacks in Canada: A History. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-6668-2.

- Morton, Desmond (2001). A short history of Canada. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-6508-8.

- Schreuder, Deryck; Ward, Stuart, eds. (2010). "Chapter 1. Australia's Empire". The Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series.

- Carter, Harold B. (1988). Delamotte, Tony; Bridge, Carl (eds.). Banks, Cook and the Eighteenth Century Natural History Tradition. pp. 4–23.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help). - Atkinson, Alan (1990). "The first plans for governing New South Wales, 1786–87". Australian Historical Studies. 24 (94): 22–40, 31. doi:10.1080/10314619008595830. S2CID 143682560.

- Lawson, Philip (2014). The East India Company: A History. Routledge.; Stern, Philip J. (2009). "History and historiography of the English East India Company: Past, present, and future!". History Compass. 7 (4): 1146–1180. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2009.00617.x.

- Knight, Roger J. B. (2013). Britain against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory, 1793–1815. Penguin UK. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-141-97702-7. OL 30961773M.

- Drury, Marjule Anne (2001). "Anti-Catholicism in Germany, Britain, and the United States: A Review and Critique of Recent Scholarship". Church History. 70 (1): 98–131. doi:10.2307/3654412. JSTOR 3654412. S2CID 146522059.; Colley, Linda (1992). Britons: Forging the Nation 1707–1837. Yale University Press. pp. 35, 53–54. ISBN 0-300-05737-7. OL 1711290M.

- Andress, David (1960). The Savage Storm: Britain on the Brink in the Age of Napoleon. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-405-51321-0. OL 34606684M.; Simms, Brendan (1998). "Britain and Napoleon". The Historical Journal. 41 (3): 885–894. doi:10.1017/S0018246X98008048. JSTOR 2639908. S2CID 162840420.

- "British History – The 1798 Irish Rebellion". BBC. 5 November 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.; Gahan, Daniel (1998). Rebellion!: Ireland in 1798. O'Brien Press. ISBN 978-0-86278-541-3. OL 403106M.

- Rose, John Holland (1911). William Pitt and the Great War. Greenwood Press. pp. 339–364. ISBN 0-837-14533-3. OL 5756027M.

- Ehrman, John (1996). The Younger Pitt: The Consuming Struggle. Constable. pp. 158–196. ISBN 0-094-75540-X. OL 21936112M.

- Cook, Chris; Stevenson, John (1980). British Historical Facts 1760–1830. The Macmillan Press.

Sources

- Black, Jeremy (2016). Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of George I, 1714–1727. Routledge. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1-317-07854-8.

- Brumwell, Stephen; Speck, W.A. (2001). Cassell's Companion to Eighteenth Century Britain. Cassell & Company. ISBN 978-0-304-34796-4.

- Costin, W. C.; Watson, J. Steven, eds. (1952), The Law & Working of the Constitution: Documents 1660–1914, vol. I: 1660–1783, A. & C. Black

- Hoppit, Julian (2000). A Land of Liberty?: England 1689–1727. ISBN 978-0-19-822842-4.

- James, Lawrence (1994). The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-10667-0. OL 9642159M.

- Langford, Paul (1989). A Polite and Commercial People: England 1727–1783.

- Marshall, Dorothy (1974). Eighteenth-Century England (2nd ed.).

- Plumb, John H. (1950). England in the Eighteenth Century.

- Robertson, Charles Grant (1911). England under the Hanoverians. Methuen & Company. ISBN 978-0-598-56207-4.

- Speck, W.A (1977). Stability and Strife: England, 1714–1760. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-83350-0.

- Williams, Basil (1962), The Whig Supremacy: 1714 – 1760 (2nd ed.), At the Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-7-230-01144-0

Further reading

- Black, Jeremy (2002). Britain as a Military Power, 1688–1815. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-98791-3.

- Brisco, Norris Arthur (1907). The economic policy of Robert Walpole. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-93374-2.

- Cannon, John (1984). Aristocratic century: the peerage of eighteenth-century England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-25729-9.

- Colley, Linda (2009). Britons: Forging the Nation 1707–1837 (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15280-7.

- Cowie, Leonard W (1967). Hanoverian England, 1714–1837. ISBN 978-0-7135-0235-0.

- Daunton, Martin (1995). Progress and Poverty: An Economic and Social History of Britain 1700–1850. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822281-1.

- Hilton, Boyd (2008). A Mad, Bad, and Dangerous People?: England 1783–1846. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921891-2.

- Hunt, William (2019) [1905]. The History of England from the Accession of George III – to the close of Pitt's first Administration. Creative Media Partners, LLC. ISBN 978-0-530-51826-8. also Gutenberg edition

- Langford, Paul (1976). The Eighteenth Century, 1688-1815. A. and C. Black. ISBN 978-0-7136-1652-1.

- Leadam, I. S (1912). The History of England From The Accession of Anne to the Death of George II.

- Marshall, Dorothy (1956). English People in the Eighteenth Century.

- Newman, Gerald, ed. (1997). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714–1837: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-0396-1.

- O'Gorman, Frank (1997). The Long Eighteenth Century: British Political and Social History 1688–1832.

- Owen, John B (1976). The Eighteenth Century: 1714–1815.

- Peters, Marie (2009). "Pitt, William, first earl of Chatham [Pitt the elder] (1708–1778)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22337. Retrieved 22 September 2017. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Porter, A.N.; Stockwell, A.J. (1989) [1986], British Imperial Policy and Decolonization, 1938-64, vol. 2, 1951–64, ISBN 978-0-333-48284-1

- Plumb, J. H (1956). Sir Robert Walpole: The Making of a Statesman.

- Porter, Roy (1990). English Society in the Eighteenth Century (2nd ed.). Penguin Publishing. ISBN 978-0-140-13819-1.

- Rule, John (1992). Albion's People: English Society 1714–1815.

- Simms, Brendan (2008). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, 1714–1783. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01332-6.

- Speck, W.A (1998). Literature and Society in Eighteenth-Century England: Ideology, Politics and Culture, 1680–1820.

- Taylor, Stephen (2008). "Walpole, Robert, first earl of Orford (1676–1745)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28601. Retrieved 22 September 2017. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Ward, A.W.; Gooch, G.P., eds. (1922). The Cambridge History of British Foreign Policy, 1783–1919. Vol. 1, 1783–1815. Cambridge, The University press.

- Watson, J. Steven (1960). The Reign of George III, 1760–1815. Oxford History of England.

- Williams, Basil (1939). The Whig Supremacy 1714–1760.

- —— (April 1900). "The Foreign Policy of England under Walpole". The English Historical Review. 15 (58): 251–276. doi:10.1093/ehr/XV.LVIII.251. JSTOR 548451.

- —— (July 1900). "The Foreign Policy of England under Walpole (Continued)". English Historical Review. 15 (59): 479–494. doi:10.1093/ehr/XV.LIX.479. JSTOR 549078.

- —— (October 1900). "The Foreign Policy of England under Walpole (Continued)". English Historical Review. 59 (60): 665–698. doi:10.1093/ehr/XV.LX.665. JSTOR 548535.

- —— (January 1901). "The Foreign Policy of England under Walpole". English Historical Review. 16 (61): 67–83. doi:10.1093/ehr/XVI.LXI.67. JSTOR 549509.

- —— (April 1901). "The Foreign Policy of England under Walpole (Continued)". English Historical Review. 16 (62): 308–327. doi:10.1093/ehr/XVI.LXII.308. JSTOR 548655.

- —— (July 1901). "The Foreign Policy of England under Walpole (Continued)". English Historical Review. 16 (53): 439–451. doi:10.1093/ehr/XVI.LXIII.439. JSTOR 549205.

Historiography

- Black, Jeremy (1987). "British foreign policy in the eighteenth century: A survey". Journal of British Studies. 26 (1): 26–53. doi:10.1086/385878. JSTOR 175553. S2CID 145307952.

- Devereaux, Simon (2009). "The Historiography of the English State during 'the Long Eighteenth Century': Part I–Decentralized Perspectives". History Compass. 7 (3): 742–764. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2009.00591.x.

- —— (2010). "The Historiography of the English State During 'The Long Eighteenth Century'Part Two–Fiscal‐Military and Nationalist Perspectives". History Compass. 8 (8): 843–865. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2010.00706.x.

- Johnson, Richard R. (1978). "Politics Redefined: An Assessment of Recent Writings on the Late Stuart Period of English History, 1660 to 1714". William and Mary Quarterly. 35 (4): 691–732. doi:10.2307/1923211. JSTOR 1923211.

- O'Gorman, Frank (1986). "The recent historiography of the Hanoverian regime" (PDF). Historical Journal. 29 (4): 1005–1020. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00019178. S2CID 159984575.

- Schlatter, Richard, ed. (1984). Recent Views on British History: Essays on Historical Writing Since 1966. pp. 167–254.

- Simms, Brendan; Riotte, Torsten, eds. (2007). The Hanoverian Dimension in British History, 1714–1837. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15462-8.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)