Great Fire of Turku

The Great Fire of Turku (Finnish: Turun palo, Swedish: Åbo brand and Russian: Пожар Або) was a conflagration in the city of Turku in 1827. It is still the largest urban fire in the history of Finland and the Nordic countries.[1] The city had burned once before, in 1681.[2][3]

Description

The fires started burning on 4 September 1827 in burgher Carl Gustav Hellman's house on the Aninkaistenmäki hill[4][5] slightly before 9 p.m.[6] The house had possibly been lit on fire by sparks flying from the chimney of a neighboring building.[7] The fire quickly swept through the northern quarter, spread to the southern quarter and jumped the Aura River, setting the Cathedral Quarter on fire before midnight. By the next day, the fire had destroyed 75% of the city. Only 25% of the city was spared, mainly the western and southern portions.

The fire destroyed the downtown area of Turku, including Turku Cathedral and the main building of the Imperial Academy of Turku, Akatemiatalo, which were badly damaged. The disaster was made possible by a dry summer preceding the event, a fire-spreading storm rising on the night of the fire, and a lack of extinguishers because a large number of the city's people happened to be visiting a market in Tampere that day. The damage was considerable and was felt for a long period of time in the aftermath of the event. 11,000 people were left homeless, and 27 casualties and hundreds of wounded were recorded.[6][8]

The night of the fire, Friedrich Wilhelm Argelander, Observator at the Imperial Academy of Turku, was in the Vartiovuori Observatory on Vartiovuorenmäki. Due to the fire, he had to stop what he was doing. In his observation log, he wrote: "Today observation was interrupted by a horrible fire that reduced Turku to ashes”. The observatory, placed on the top of a tall hill, was spared though and work was continued on 9 September.[9] As the rest of the academy has suffered great damage, its indispensable activities such as meetings of the consistory and the Chancellor's Office, were moved to the observatory. Most Finnish archives, including practically all material from the Middle ages, were destroyed in the fire.

Aftermath

At the time of the fire, and for some time afterwards, Turku was the largest city in Finland, which is why the Great Fire of Turku was a major national disaster.[1] As a result of the fire, the Imperial Academy of Turku was transferred to Helsinki, which in 1812 had been made the capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland.[10]

Governor-General of the Grand Duchy of Finland Arseniy Zakrevskiy was responsible for rebuilding the city after the fire. His proposal resulted in the Senate of Finland selecting Architect Carl Ludvig Engel to create the new city plan for Turku.[11] Downtown Turku is still based on Engel's grid plan, which was approved on 15 December 1828. The largest buildings in downtown Turku, the cathedral and Akatemiatalo, were refurbished, and some of the other buildings, such as the Old Town Hall and the former sugar factory, were rebuilt. The majority of the city, however, had to be completely rebuilt. Turku's grid plan design had a significant influence on how other Finnish towns were laid out.

The Cloister Hill area, which was completely spared due to its location on the outskirts of the area hit by the fire, was protected and opened up as an open-air museum in 1940.

Gallery

Great Fire of Turku, Robert Wilhelm Ekman, unknown date

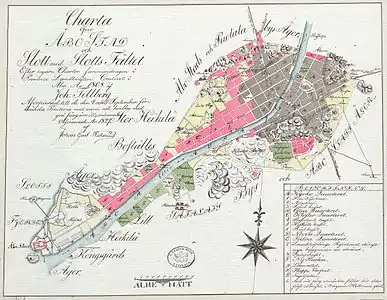

Great Fire of Turku, Robert Wilhelm Ekman, unknown date Map of Åbo after the 1827 fire. Destroyed areas are in grey, surviving areas in red. The red blocks to the South East are now the Luostarinmäki museum.

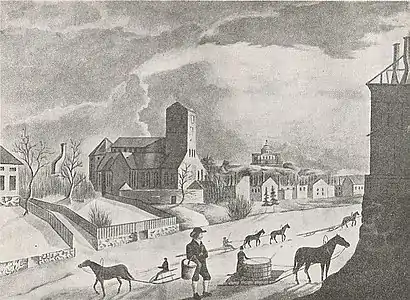

Map of Åbo after the 1827 fire. Destroyed areas are in grey, surviving areas in red. The red blocks to the South East are now the Luostarinmäki museum. Turku in the winter of 1827, only a few months afterwards

Turku in the winter of 1827, only a few months afterwards

See also

References

- Leppänen, Päivi (4 September 2022). "Turku paloi poroksi päivälleen 195 vuotta sitten – syyllinen ei ollut mikään piika, vaan paloturvallisuudesta piittaamaton byrokratia". Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- Välimäki, Mari (2 May 2019). "Turun palo 1681 – mitä raastuvanoikeuden pöytäkirjat kertovat?". Lastuja Suomen historiasta. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Hannula, Henri M. (27 April 2019). "Lastuja tutkimusprojektista: Turun palo vuonna 1681 hollantilaisasiamiehen silmin". Historia elää. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- "Turun palon alkupaikka". Visit Turku. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Rekola, Juuso (4 July 2019). "Turun palo 1827 oli aikansa kansainvälinen mediailmiö". Agricola-verkko. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Korteniemi, Jaakko (4 September 2017). "Turku roihusi 190 vuotta sitten mutta myytit elävät yhä". Tiedetuubi. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Välilä, Anu (25 April 2008). "Turun palosta syytetty Hellmanin talon piika saa synninpäästön". Turun Sanomat. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- "Turun palo". Agricola-verkko Vintti. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Argelander, F.W.A. (1831). Observationes astronomicae in Specula Universitatis Litterariae Fennicae factae, vol. 2. F.A. Meyer. p. 110.

- Laaksonen, Teemu (5 September 2017). "Turun suurpalo vuonna 1827 mullisti Suomen – kirjailija Mike Pohjola epäilee tsaarin juonineen taustalla". Yle. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- "Turun palo". Yle. Retrieved 4 July 2020.