Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

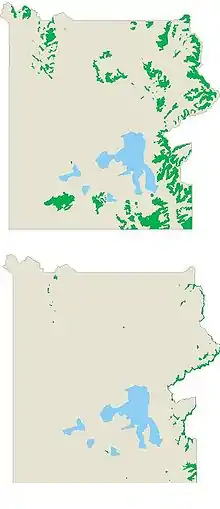

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) is one of the last remaining large, nearly intact ecosystems in the northern temperate zone of the Earth.[1] It is located within the northern Rocky Mountains, in areas of northwestern Wyoming, southwestern Montana, and eastern Idaho, and is about 22 million acres (89,000 km2).[2] Yellowstone National Park and the Yellowstone Caldera 'hotspot' are within it.[1]

The area is a flagship site among conservation groups that promote ecosystem management. The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) is one of the world's foremost natural laboratories in landscape ecology and Holocene geology, and is a world-renowned recreational destination. It is also home to the diverse native plants and animals of Yellowstone.

History

Yellowstone National Park boundaries were drawn in 1872 with the intent to include all the known geothermal basins in the region. As landscape ecology considerations were not incorporated into original boundary, revisions were suggested to conform more closely to natural topographic features, such as the ridgeline of the Absaroka Range along the east boundary. In 1929, President Hoover signed the first bill changing the park's boundaries: The northwest corner now included a significant area of petrified trees; the northeast corner was defined by the watershed of Pebble Creek; the eastern boundary included the headwaters of the Lamar River and part of the watershed of the Yellowstone River. In 1932, President Hoover issued an executive order that added more than 7,000 acres (2,800 ha) between the north boundary and the Yellowstone River, west of Gardiner. These lands provided winter range for elk and other ungulates.[3] By the 1970s, the grizzly bear's (Ursus arctos) range in and near the park became the first informal minimum boundary of a theoretical "Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem" that included at least 4,000,000 acres (16,000 km2). Since then, definitions of the greater ecosystem's size have steadily grown larger. A 1994 study listed the size as 19,000,000 acres (76,890 km2), while a 1994 speech by a Greater Yellowstone Coalition leader enlarged that to 20,000,000 acres (80,000 km2).

In 1985 the United States House of Representatives Subcommittees on Public Lands and National Parks and Recreation held a joint subcommittee hearing on Greater Yellowstone, resulting in a 1986 report by the Congressional Research Service outlining shortcomings in inter-agency coordination and concluding that the area's essential values were at risk.

Protected areas

Federally managed areas within the GYE include:

- United States National Park Service (NPS) — Yellowstone National Park, Grand Teton National Park, and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway.

- United States National Forest Service (USFS) — Gallatin, Custer, Beaverhead-Deerlodge, Caribou-Targhee, Bridger-Teton, and Shoshone National Forests

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) — National Elk Refuge, Red Rock Lakes and Grays Lake National Wildlife Refuges

Ten distinct National Wilderness Areas have been established within the GYE's National Forests since 1966, mandating a higher level of habitat protection than the USFS otherwise uses.

The GYE also encompasses some privately held and state lands surrounding those managed by the U.S. Government.

The Trust for Public Land has protected 67,000 acres (27,000 ha) over about 40 projects in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.[2]

Management by species

Ecological management has been most often advanced through concerns over individual species rather than over broader ecological principles. Though 20 or 30 or even 50 years of information on a population may be considered long-term by some, one of the important lessons of Greater Yellowstone management is that even half a century is not long enough to give a full idea of how a species may vary in its occupation of a wild ecosystem.

The Yellowstone hot springs are important for their diversity of thermophilic bacteria. These bacteria have been useful in studies of the evolution of photosynthesis and as sources of thermostable enzymes for molecular biology. Although the smell of sulfur is common and there are some sulfur fixing cyanobacteria, it has been found that hydrogen is being used as an energy source by extremophile microbes.

Flora

Among native plants of the GYE, whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) is a species of special interest, in large part because of its seasonal importance to grizzly bears, but also because its distribution could be dramatically reduced by relatively minor global warming. In this case, researchers do not have a good long-term data set on the species, but they understand its ecology well enough to project declining future conservation status. A more immediate and serious threat to whitebark pines is an introduced fungal rust disease, White Pine Blister Rust (Cronartium ribicola), which is causing heavy mortality in the species. Occasional resistant individuals occur, but in the short to medium term, a severe population decline is expected.

Estimates of the decline of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) on the park's northern range since 1872 range from 50% to 95%. Perhaps no conservation controversy underway in Greater Yellowstone more clearly reveals the need for comprehensive interdisciplinary research.

Several factors are suspected in the quaking aspen's changing status, including:

- Native American influences on numerous mammal species and on fire ecology-return intervals before the creation of the park in 1872.

- European influences on wildfire frequency since 1886; regional climate warming.

- Human harvests of beaver and ungulates in the first 15 years of the park's history, and of wolves and other predators before 1930.

- Human settlement on traditional ungulate migration routes north of the park since 1872; ungulate (especially elk) effects on all other parts of the ecosystem since 1900; and human influences on elk distribution in the park.

Fauna

Anecdotal information on grizzly bear abundance dates to the mid-19th century, and administrators have made informal population estimates for more than 70 years. From these sources, ecologists know the species was common in Greater Yellowstone when Europeans arrived and that the population was not isolated before the 1930s, but is now. Researchers do not know if bears were more or less common than now.

A 1959-1970 bear study suggested a grizzly bear population size of about 176, later revised to about 229.[1] Later estimates have ranged as low as 136 and as high as 540; the most recent is a minimum estimate of 236,[1] but biologists think there may be as many as 1,000 bears in the ecosystem. Although the Greater Yellowstone population is relatively close to recovery goals, the plan's definition of recovery is controversial. Thus, even though the population may be stable or possibly increasing in the short term, in the longer term, continued habitat loss, climate change, and increasing human activities may well reverse the trend.

Yellowstone cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarki bouvieri) have suffered considerable declines since European settlement, but recently began flourishing in some areas. Especially in Yellowstone Lake itself, long-term records indicate an almost remarkable restoration of robust populations from only three decades ago when the numbers of this fish were depleted because of excessive harvest. Its current recovery, though a significant management achievement, does not begin to restore the species' historical abundance. Also, they declined because of invasive lake trout. An aggressive lake trout removal program has caused the cutthroats to rebound.

Early accounts of pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) in Greater Yellowstone described herds of hundreds seen ranging through most major river valleys. These populations were decimated by 1900, and declines continued among remaining herds. On the park's northern range, pronghorn declined from 500 to 700 in the 1930s to about 122 in 1968. By 1992 the herd had increased to 536.

Gray Wolf reintroduction

The park is a commonly cited example of apex predators affecting an ecosystem through a trophic cascade.[4] After the reintroduction of the gray wolf in 1995, researchers noticed drastic changes occurring. Elk, the primary prey of the gray wolf, became less abundant and changed their behavior, freeing riparian zones from constant grazing. The respite allowed willows and aspens to grow, creating habitat for beaver,[5] moose, and scores of other species. In addition to the effects on prey species, the gray wolf's presence also affected the park's grizzly bear population. The bears, emerging from hibernation, chose to scavenge off wolf kills to gain needed energy and fatten up after fasting for months. Dozens of other species have been documented scavenging from wolf kills.[6]

See also

- Ecology of the Rocky Mountains

- Ecology of the Rocky Mountains topics

References

-

This article incorporates public domain material from Schullery, Paul (1995). "The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem". Our Living Resources. U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2006-09-27.

This article incorporates public domain material from Schullery, Paul (1995). "The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem". Our Living Resources. U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2006-09-27. - "Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem". The Trust for Public Land. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from Yellowstone National Park - Birth of a National Park - Boundary Adjustments. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

This article incorporates public domain material from Yellowstone National Park - Birth of a National Park - Boundary Adjustments. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2022-06-24. - Weston, Phoebe (2022-06-23). "'People may be overselling the myth': should we bring back the wolf?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- "Beyond the Headlines". Living on Earth. March 20, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- Smith, Douglas W.; Peterson, Rolf O.; Houston, Douglas B. (2003-04-01). "Yellowstone after Wolves". BioScience. 53 (4): 330–340. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0330:YAW]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0006-3568. S2CID 56277360.

Further reading

- Turner, Jack (2008). Travels in Greater Yellowstone. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-26672-1.