Greater blue-ringed octopus

The greater blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena lunulata) is one of four species of extremely venomous blue-ringed octopuses belonging to the family Octopodidae. This particular species of blue-ringed octopus is known as one of the most toxic marine animals in the world.

| Greater blue-ringed octopus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hapalochlaena lunulata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Octopoda |

| Family: | Octopodidae |

| Genus: | Hapalochlaena Robson, 1929 |

| Species: | H. lunulata |

| Binomial name | |

| Hapalochlaena lunulata | |

Physical characteristics

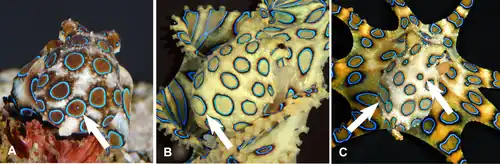

The greater blue-ringed octopus, despite its vernacular name, is a small octopus whose size does not exceed 10 centimeters, arms included, for an average weight of 80 grams. Its common name comes from the relatively large size of its blue rings (7 to 8 millimeters in diameter), which are larger than those of other members of the genus and help to distinguish this type of octopus. The head is slightly flattened dorsoventrally (front to back) and finished in a tip. Its eight arms are relatively short.

There are variable ring patterns on the mantle of Hapalochlaena lunulata with varied coloration in correlation to their ambient environment, from yellow ocher to light brown or even white-ish (when inactive). The blue rings, which number around 60, are spread throughout the entirety of its skin. The rings are roughly circular in shape and are based on a darker blotch than the background color of the skin. A black line, with thickness varying to increase contrast and visibility, borders the electric blue circles. The blue rings are an aposematic adornment to clearly show to all potential predators that the octopus is highly venomous. The octopus also has characteristic blue lines running through its eyes.

Flashing behavior

The octopus usually flashes its iridescent rings as a warning signal, each flash lasting around a third of a second. To test the theory if blue-ringed octopuses could produce their own blue iridescence, scientists bathed the octopus samples in a wide range of chemicals that were known to affect chromatophores and iridophores. It was found that none of the chemicals used affected the octopuses' ability to produce its blue rings. It was also found that after examining the blue rings (specifically the iridophores) were seen to shift to the UV end of the spectrum which is a defining characteristic of multi-layer reflectors. It was also found that the iridophores are nicely tucked into the modified skin folds, kind of like pouches, which could be contracted by the muscles that connect the center of each ring to the rim. When the muscles then relax, the muscles around the perimeter of the ring contract which in turn causes the pouch to open to expose the iridescent flash. The octopus can then expand the brown chromatophores on either side of its ring to enhance the contrast of its iridescence. After all of the testing was complete, it was determined that the muscle contracting mechanisms was key to how the blue-ringed octopus portrayed its iridescent signaling success.[2]

Distribution and habitat

The greater blue-ringed octopus is a benthic animal that has a solitary way of life and is widespread throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Indo-West Pacific, from Sri Lanka to the Philippines and from Australia to Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. The animal prefers shallow waters with a mixed seabed (such as rubble, reefs and sandy areas). As is true for all octopuses, it lives in a burrow and only comes out to search for food or a mate. The entrance of the shelter is littered with remains from meals (empty shells and crab shell and legs) and is easily identifiable.[3]

Diet

The blue-ringed octopus diet typically consists of small crabs and shrimp. They also tend to take advantage of small injured fish if they can catch them. Its known hunting behavior consists of pouncing on its prey, seizing it with its arms, and then pulling it towards its mouth. It uses its horny beak to pierce through the tough crab or shrimp exoskeleton, releasing its venom. The venom paralyzes the muscles required for movement, which effectively kills the prey.

Sex identification and mating behavior

The initiation of physical contact is completely independent from sex, size, or residency status which left no notable changes of behavior based on sex alone. However, Spermatophores are only released during sexual interaction with females but not with males which indicates that upon copulation, the male can distinguish the difference on whether to inseminate or not. The copulation times between male-female are roughly 160.5 minutes, while the copulation times with the male-male interactions lasted about 30 seconds. Ultimately the studies that were conducted determined that until copulation occurs, prior to insertion of the hectocotylus, the male cannot determine the difference in sex.

Reproduction

The breeding season varies according to geographical area. The female lays between 60 and 100 eggs, which are kept under the female's arms during the incubation period, which lasts about a month. Newborns have a brief planktonic development passage before settling on the seabed.

The mating ritual begins when a male approaches a female and begins to caress her with his modified arm, the hectocotylus. Males then climb on the female's back, at times completely engulfing the female’s mantle obstructing her vision. The hectocotylus is inserted under the mantle of the female and spermatophores are released into the female’s oviduct. Males die after mating. The female then lays between 50 and 100 eggs and guards them by carrying them under her arm until they hatch about 50 days later into planktonic paralarvae. The female then dies as she refuses to eat while she guards her eggs. The blue-ringed octopus is about the size of a pea when hatched then grows to reach the size of a golf ball as an adult. They mature quickly and begin mating the following autumn. Their average lifespan is about 2 years.

Potential danger

The greater blue-ringed octopus is capable of inflicting a deadly bite to its predators that can potentially be fatal to humans. Octopuses from genus Hapalochlaena have two kinds of venom glands that impregnate their saliva. One is used to immobilize the hunted crustaceans before eating them. The second, tetrodotoxin, is used for defense and is found in several other sea creatures such as pufferfish. Tetrodotoxin, also known as TTX, is secreted from the posterior salivary glands which is connected to the beak. The greater blue-ringed octopus is known as one of the most venomous marine animals in the entire world. For humans, the minimal lethal dose of tetrodotoxin is estimated to be about 10,000 MU, which is about 2 mg in crystal form. TTX does not decompose during heating or boiling and there is no known antidote or antitoxin for this toxin. It is believed that the TTX serves as a hunting tool for paralyzing prey as well as a defense mechanism to other predators.[4] This toxin is a powerful neurotoxin and a strong paralytic. The bite is painless to humans but effects appear any time between 15 and 30 minutes and up to four hours, though the rate of onset of symptoms varies by individual, and children are more sensitive to the toxins.

The first phase of the poisoning is characterized by facial and extremity paresthesia, and the victim feels tingling and/or numbness on the face, tongue, lips, and other body extremities. The victim may also suffer excessive sweating, severe headaches coupled with dizziness, speech problems, hypersalivation, moderate emesis, movement disorders, a feeling of weakness, cyanosis to extremities and lips and petechial hemorrhages on the body.

The second phase of poisoning usually occurs after eight hours and includes hypotension and generalized spastic muscle paralysis. Death may occur between 20 minutes and 24 hours after the onset of symptoms, usually resulting from respiratory paralysis. Throughout each of the phases of poisoning, the state of consciousness of the victim is unaffected.[5]

Genetics

Greater Blue Ringed Octopuses express VGSC (HlNav1) gene mutations that greatly reduce the channels TTX binding affinity which in turn render the octopus TTX resistant. TTX selectively binds and blocks the ion-conducting pore of the voltage-gated sodium channel which are responsible for the ability of an organism to move. The greater blue-ringed octopus naturally produced TTX and bears a phenotype in the genus for the resistance to TTX. It was found that the resistance was caused by a combination of amino acid substitutions in the TTX binding sites for the primary voltage-gated sodium ion channel.

References

- Huffard, CL; Caldwell, RL; DeLoach, N; Gentry, DW; Humann, P; MacDonald, B.; Moore, B.; Ross, R.; Uno, T.; Wong, S. (2008). "Individually Unique Body Color Patterns in Octopus (Wunderpus photogenicus) Allow for Photoidentification". PLOS ONE. 3 (11): e3732. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3732H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003732. PMC 2579581. PMID 19009019.

- Mathger, L. M.; Bell, G. R. R.; Kuzirian, A. M.; Allen, J. J.; Hanlon, R. T. (2012-10-10). "How does the blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena lunulata) flash its blue rings?". Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (21): 3752–3757. doi:10.1242/jeb.076869. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 23053367.

- "Greater Blue-ringed Octopus - Encyclopedia of Life".

- "Tétrodotoxine". poisonpedia.e-monsite.com (in French). Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- Fotouhie, Azadeh; Desai, Hem; King, Skye; Parsa, Nour Alhoda (2016-06-06). "Gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced vitamin K deficiency". BMJ Case Reports. 2016: bcr2016214437. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-214437. ISSN 1757-790X. PMC 4904401. PMID 27268289.

External links

- "CephBase: Greater blue-ringed octopus". Archived from the original on 2005-08-17.

- Animal Diversity Web

- Photos of Greater blue-ringed octopus on Sealife Collection