Greco Mafia clan

The Greco Mafia family (Italian pronunciation: [ˈɡrɛːko]) is historically one of the most influential Mafia clans in Sicily and Calabria, from the late 19th century. The extended family ruled both in Ciaculli and Croceverde Giardini, two south-eastern outskirts of Palermo in the citrus growing area and also rural areas of Calabria where they controlled the olive oil market. Members of the family were important figures in the Sicilian Cosa Nostra and Calabrian 'Ndrangheta. Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco was the first ‘secretary’ of the Sicilian Mafia Commission, while Michele Greco, also known as The Pope, was one of his successors.

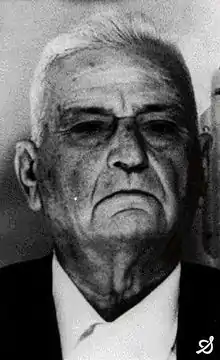

Mafia boss Giuseppe Greco, also known as "Piddu u tinenti" (Piddu the lieutenant) | |

| Founded | Late 19th century |

|---|---|

| Named after | Greco family |

| Founding location | Ciaculli and Croceverde Giardini, two south-eastern outskirts of Palermo |

| Years active | Decline in the 2000s but still active with a very strong influence |

| Territory | Ciaculli and Croceverde Giardini, two south-eastern outskirts of Palermo and Calabria Dasà |

| Ethnicity | Sicilian/Calabrian |

| Membership | Sicilian Mafia |

| Activities | Palermo wholesale market; Gioua Taurio Port racket (1950s); cigarette smuggling and heroin trafficking; money laundering |

| Allies | Croceverde faction alliance with the Corleonesi (Second Mafia War 1981-1983) |

| Rivals | Acquasanta Mafia clan (Palermo wholesale market war in the mid 1950s) La Barbera brothers (First Mafia War in the early 1960s) Ciaculli faction rivalry with the Corleonesi |

| Notable members | Giuseppe Greco, aka "Piddu u tinenti" (Piddu the lieutenant) Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco Giuseppe "Pinè" Greco Salvatore "The Engineer" Greco Nicola "Nicolazzo" Greco Michele Greco aka The Pope Salvatore "The Senator" Greco |

According to the pentito Antonio Calderone "the Grecos effectively exercised power in the whole of Sicily." According to Giovanni Brusca the Greco family was very important and the ones who tipped the balance in every internal Mafia war.[1]

Early history

The exact origins of the Greco Mafia clan are unclear. Greco is a common name in Sicily and especially so in Ciaculli, leading to several unrelated Mafia groups in the island to carry the name. At the turn of the 20th century, the Sangiorgi report mentions a Salvatore Greco as the capomafia of Ciaculli and a relative of his, also named Salvatore Greco, as another capomafia in the area, so it is possible that both groups had already diverged, or were not even related, by that point.[2][3][4]

The boss of the Croceverde Giardini, Giuseppe Greco, also known as "Piddu u tinenti" (Piddu the lieutenant), was gabelloto of I Giardini, an estate of about 300 hectares of citrus orchards, in particular the tangerines that make the area of Croceverde and Ciaculli famous.[5]

The Grecos were typical representatives of the rural Mafia. In 1916, they ordered the murder of a priest who had denounced the Mafia's interference in the administration of ecclesiastical revenues and charity funds during a Sunday sermon.[2][4] In 1921, a Greco who had suffered a sgarro (a personal affront) killed two shepherds along with their flock of sheep. In 1929, a Greco fired twenty bullets into an enemy's great casks of wine and then sat down amid the foaming splinters to smoke his pipe.[6]

The Greco War: interfamily feud

In 1939 a bloody vendetta between both clans started during a brawl about a question of honour among youngsters of the two clans. The son of Giuseppe Greco, also known as "Piddu u tinenti" (Piddu the lieutenant), the boss of Croceverde Giardini cosca, was killed. In 1946–47, the bloody internal feud between the factions in Ciaculli and Croceverde Giardini reached a climax. On August 26, 1946, Giuseppe Greco, the boss of the Ciaculli clan and a brother-in-law of "Piddu u tinenti", and his brother Pietro Greco were killed with machine guns and grenades. The Ciaculli faction reacted a few months later when two of Piddu the lieutenant's men were shot with a lupara, the typical Sicilian short-barrelled shotgun. In revenge the Giardini cosca kidnapped two members of the rival faction who were never seen again, a so-called lupara bianca.[4][5][7]

The struggle between the clans came to a peak with a full-scale gunfight in the main square of Ciaculli on September 17, 1947. First, an important member of the Giardini cosca was shot down by a machine gun. When it became clear he was not dead yet, two women of the Ciaculli clan, Antonina (51) and Rosalia (19) the widow and daughter of one of the bosses killed the year before, went down into the street and finished the victim off with kitchen knives. In return, the brother and sister of the victim shot the women; Antonina was wounded and her daughter killed. Their attacker was then shot and killed by Antonina's then 18-year-old son, Nicola Greco, also called Nicolazzo.[4][5][7]

In total, eleven members of the two clans died and several others were wounded in the feud, before other Palermo Mafia bosses started to put pressure on Piddu the lieutenant to end the bloody feud, which drew too much attention. Moreover, Piddu was expected to take care for both factions of the feuding clans, after the killing of the bosses of the rival faction. His status depended on how he would manage the situation.[4]

Mediation

Piddu the lieutenant asked for mediation from Antonio Cottone, the boss of the Mafia family of Villabate, a town close to Ciaculli and Croceverde. Cottone, who had been deported from the US, was an influential mafioso both in Palermo as in his native village Villabate, and still had good connections in the US, in particular with Joe Profaci, who came from the same village. At the time, Profaci was in Sicily and it seems he played an important role in the peace negotiations.[4][5][7]

The peace between the two rival factions of the Greco clan was settled by giving the rights of the Giardini estate to Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco (the son of Giuseppe Greco of Ciaculli) and his cousin Salvatore Greco, also known as "l'ingegnere" (The Engineer) or "Totò il lungo" (Totò the tall) (the son of Pietro Greco of Ciaculli). They became co-owners of a citrus fruit export business and partners in a bus company.

Historians are sceptical about the blood feud theory of the struggle. At stake was the control of the citrus plantations, the management of the citrus derivatives business and transport, as well as control over the wholesale markets in eastern Palermo. Six of the victims in the war did not bear the Greco name. The blood feud legend was probably spread around to hide the real motives behind the struggle.[4][5][7]

Descendants of the Ciaculli faction

Giuseppe Greco and Pietro Greco, of the Ciaculli faction, both had many sons, four of whom became particularly powerful and influential mafiosi within Cosa Nostra:

- Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco (the son of Giuseppe Greco and Santa Greco, the sister of Piddu the lieutenant)

- Giuseppe "Pinè" Greco, the brother of Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu".

- Salvatore Greco, (the son of Pietro Greco), also known as "l'ingegnere" (the engineer) or "Totò il lungo" (Totò the tall).

- Nicola "Nicolazzo" Greco, the brother of "The Engineer"

Descendants of the Croceverde Giardini faction

Giuseppe Greco, also known as "Piddu u tinenti", the boss of Croceverde Giardini faction, had two sons that rose to prominence in Cosa Nostra:

- Michele Greco also known as The Pope.

- Salvatore Greco also known as The Senator. He married the daughter of Nino Cottone, the peacemaker between the two factions.

- Leandro Greco, grandson of Michele Greco also known as The Prince.[8]

- Giuseppe Greco, also known as "U Minnuni", son of "The Senator".

Piddu the lieutenant asked for mediation from Antonio Cottone, the boss of the Mafia family of Villabate, a town close to Ciaculli and Croceverde. Cottone, who had been deported from the US, was an influential mafioso both in Palermo as in his native village Villabate, and still had good connections in the US, in particular with Joe Profaci, who came from the same village. At the time, Profaci was in Sicily and it seems he played an important role in the peace negotiations.[4][5][7]

Consolidation

Piddu the lieutenant withdrew from active life as a mafioso and settled in a modern house in Palermo, where he consolidated and expanded his friendships among the ‘accepted’ section of society, protecting his younger relations when they got into trouble with the law.[5][9] His influence in the higher circles of Palermo was considerable. Cardinal Ernesto Ruffini accepted an invitation of Piddu Greco to bless the new church of Croceverde-Giardini and a dinner afterwards.[10]

The Grecos were protagonist in the violent conflict about the Palermo fruit and vegetable wholesale market that was moved from the Zisa area to Acquasanta near the port in January 1955, disturbing the delicate power balances within Cosa Nostra. The Acquasanta Mafia clan tried to muscle in on the protection racket that traditionally belonged the "Mafia of the Gardens" — such as the Grecos and Cottone — because it now fell under their territory. The bosses of the Acquasanta Mafia clan, Gaetano Galatolo and Nicola D’Alessandro, as well as Francesco Greco from the Ciaculli clan, a major wholesaler of fruit and vegetables, were killed in a dispute over the protection rackets.[11][12] Soon after, the brother and a friend of Greco also disappeared in a lupara bianca.[13]

Some villages just outside Palermo, like Bagheria and Villabate, flared up with the same kind of violence for the control of irrigation, transport, and wholesale markets. On August 22, 1956, Nino Cottone was killed as well. In the end the Acquasanta had to split the profits of the wholesale market racket with the Greco Mafia clan of Ciaculli, who traditionally controlled fruit and vegetable supply to Palermo wholesale market.[5][12][14]

On the Commission

Although descendants of the old, established rural Mafia, the cousins Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco and Salvatore "The Engineer" Greco quickly learned to profit from the post-war economic boom and became involved in cigarette smuggling and heroin trafficking. They both participated at the Grand Hotel des Palmes Mafia meeting in October 1957 between prominent American and Sicilian mafiosi. Heroin trafficking between these two groups might have been discussed, but there certainly was not a general agreement on the heroin trade between the Sicilian Mafia and the American Cosa Nostra, as is often suggested.

At one of the meetings American Mafia boss Joe Bonanno suggested the Sicilians to form a Sicilian Mafia Commission to avoid violent disputes, following the example of the American Mafia that had formed their Commission in the 1930s. The Sicilians agreed and Tommaso Buscetta, Gaetano Badalamenti and Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco set the ground rules. Somewhere in 1958 the Sicilian Mafia composed its first Mafia Commission. "Ciaschiteddu" Greco was appointed as its first segretario (secretary), essentially a "primus inter pares" – the first among equals.[15] That position came to him almost naturally because he headed one of the most influential Mafia clans at the time. The Commission, however, was not able to prevent the outbreak of a violent Mafia War in 1962.

First Mafia War

The cousins Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco and Salvatore "The Engineer" Greco of the Ciaculli family were also protagonists in the First Mafia War between rival clans in Palermo in the early 1960s for the control of the profitable opportunities brought about by rapid urban growth and the illicit heroin trade to North America. The conflict was sparked by a quarrel over an underweight shipment of heroin and the murder of Calcedonio Di Pisa – an ally of the Grecos – in December 1962. The Grecos suspected the brothers Salvatore and Angelo La Barbera of the attack. The clash between the Grecos and the La Barberas involved an old and a new Mafia. According to Antimafia judge Cesare Terranova the Grecos "represented the traditional Mafia, the Mafia in trappings of respectability … and they are linked by a dense network of friendships, interests, and protections with the leading Mafiosi of the Palermo area. They occupy a position of preeminence in the sector of cigarette and drug smugglers. The La Barberas, in contrast, come out of obscurity and their power consists especially in their enterprising ways and their following – a determined band of professional killers."[16]

Early into the war, Salvatore La Barbera was murdered after being lured into a meeting by Cicchiteddu, and his body was made to disappear with the help of Gigino Pizzuto, capomandamento of Castronovo di Sicilia. However, the war continued unabated, because behind the scenes, the actual violence was being perpetrated by Michele Cavataio, Pietro Torretta and other families allied to them, who had deliberately framed the La Barberas in an effort to get them to infight with the Grecos, and then eliminate both factions to take control for themselves. 1963 saw a series of car bomb attacks against the Grecos and their allies, culminating on June 30, 1963, when a car bomb meant to kill Salvatore Greco exploded near the Grecos' house in Ciaculli, killing seven police and military officers sent to defuse it after an anonymous phone call. The outrage over the Ciaculli Massacre changed the Mafia war into a war against the Mafia. It prompted the first concerted anti-mafia efforts by the state in post-war Italy. The Sicilian Mafia Commission was dissolved and of those mafiosi who had escaped arrest many went abroad. Even the old Piddu Greco was arrested in October 1965, and send into internal banishment from Sicily in May 1966.[10]

The repression caused by the Ciaculli Massacre disarranged the Sicilian heroin trade to the United States. Mafiosi were banned, arrested and incarcerated. The Sicilian Mafia Commission was suspended and Mafia families themselves were temporarily dissolved. Control over the trade fell into the hands of a few fugitives: the Greco cousins, Pietro Davì, Tommaso Buscetta and Gaetano Badalamenti, while control of the organization back in Sicily was temporarily handed to Nino Sorci "U Riccu", Salvatore Greco's right-hand man.[17]

Salvatore "The Engineer" and "Ciaschiteddu" Greco were sentenced in absentia to respectively 10 and 4 years in prison at the Trial of the 114 in 1968 that was initiated as the result of the First Mafia War, but as they had been on the run since 1963, they did not serve a day. "Ciaschiteddu" Greco had moved to Venezuela, and the whereabouts of "The Engineer" were completely unknown. In 1973 they were both given the maximum period of five years of internal banishment at the remote island of Asinara, but they were nowhere to be found.[18]

Re-emergence and prelude to the war

In the 1970s the Mafia recuperated. The Commission was re-established in 1974 under the leadership of Gaetano Badalamenti, an old ally of Salvatore Greco. However, the Ciaculli faction of the Greco clan was by this time in disarray, as Ciaschiteddu and The Engineer never permanently returned to Sicily and continued to manage their illicit businesses from abroad, while the brother of Ciaschiteddu, Giuseppe "Pinè" Greco, remained in Sicily as the underboss of the Ciaculli family. This, however, allowed the Grecos from Croceverde to rise to much greater prominence within the organization. The brothers Michele Greco and Salvatore Greco operated low profile and were able to enter into relationships with businessmen, politicians, magistrates and law enforcement officials through their membership of Masonic lodges.[19] Salvatore Greco's nickname was "The Senator" for his political connections. He was the kingmaker of Christian Democrat politicians such as Giovanni Gioia, Vito Ciancimino and Giuseppe Insalaco.[20] Bankers and other notables were invited to wine and dine and take part in hunting parties at Michele Greco's estate La Favarella. The estate was also used as a refuge for mafiosi on the run, and to set up a heroin laboratory.[21][22] Michele Greco became the capo-mandamento of the Ciaculli-Croceverde Gardini area and had a seat in the commission.

Tensions within the Mafia would begin to rise starting from 1975, when the up and rising faction of the Corleonesi led by Salvatore Riina kidnapped and murdered Luigi Corleo, the father-in-law of Nino Salvo of Salemi, closely connected to the traditionally powerful families of the Mafia of Palermo. A fracture within the organization became more and more apparent between those families closely allied to Stefano Bontade, Salvatore Inzerillo, Giuseppe Di Cristina, Giuseppe Calderone, and those instead allied with the Corleonesi, who under the leadership of the ambitious Riina began plotting to control the entire organization. Initially this did not directly impact the Grecos, or indeed most of the families based in Palermo, and was mainly aimed at undermining the prestige of Gaetano Badalamenti, the Corleonesi's former employer whom Riina particularly detested. Through his various new alliances in the Commission, Riina and his men had managed to isolate Badalamenti and strike down nearly all of his proposals in the voting process, leading to repeated demands for a new leader. On 24 October 1975, Nicola "Nicolazzo" Greco, the brother of Salvatore "The Engineer", who lived in Brazil and ran a construction company with his brother Paolo, together his driver Giovannello Greco, also a man of honour from the Ciaculli family, visited the boss of Catania Giuseppe Calderone. Greco informed Calderone that they intended to nominate Michele Greco as the new representative of the whole province of Palermo. Calderone expressed skepticism at this idea, due to Greco's perceived bland and weak personality, but Nicola Greco reassured Calderone and his allies that behind the scenes he and Antonino Mineo, the capomafia of Bagheria, would have been able to control Michele Greco in order to maintain peace and stability within the Commission. This, however, proved to be a grave error, as unbeknownst to Nicola Greco and his allies, Michele Greco had already secretly allied himself with Salvatore Riina, and allowed them to carry out several unsanctioned murders whilst feigning ignorance on who was responsible during Commission meetings.

Tensions came to a head in late 1977, when the boss of Riesi, Giuseppe Di Cristina, narrowly survived an assassination attempt, in which two of his most trusted men were murdered. The order came from Salvatore Riina who was greatly expanding his power within many towns in both eastern and western Sicily, and Di Cristina blamed the boss of Vallelunga Pratameno, Francesco Madonia, a strong ally of Riina, for having organized the attack. Di Cristina, Calderone and Badalamenti thus began plotting the murder of Francesco Madonia in retaliation, and sought the help and counsel of Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco, who in February 1978 came all the way from Venezuela and met with them in the offices of the Costanzo building company in Catania. Greco, however, thought attacking the Corleonesi head-on to be premature, and invited Giuseppe Di Cristina to emigrate with him to Venezuela for a time, in an effort to let tensions dissipate. Greco then returned to Venezuela but he died shortly after of natural causes. This deprived the Ciaculli faction of their most charismatic leader, and from then on it was his cousin Nicola "Nicolazzo" Greco who became the most important leader of the Ciaculli Grecos. Eventually, Di Cristina and his allies decided to go ahead with their plan and Francesco Madonia of Vallelunga was murdered.

In the aftermath of the murder, Riina managed to use the alliances he had secured thus far in the Commission to get Badalamenti expelled from the Mafia after blaming him for the assassination. Other important leaders, such as Stefano Bontade and Giuseppe Calderone, were likewise blamed and nearly expelled themselves. Giuseppe Di Cristina, finding himself increasingly isolated and aware that the Corleonesi would have tried killing him again, decided to become an informant for the Carabinieri. After a few meetings, however, this collaboration was discovered by Michele Greco, and Giuseppe Di Cristina was murdered in Palermo on 30 May 1978. The boss of Catania, Giuseppe Calderone, was also killed by order of Riina several months later, on 8 September. Calderone had been the secretary of the Interprovincial Commission, set up in 1975, which after its first year, where monthly meetings were held in the various provinces of Sicily, always saw its meetings held at the Favarella estate owned by Michele Greco, a sign of his growing importance within Cosa Nostra. Following Calderone's death, the representative of Agrigento, Giuseppe Settecassi, became the new secretary, but after the Corleonesi killed him too on 23 March 1981, Michele Greco finally became the secretary of the Interprovincial Commission, alongside already being the leader of the one in Palermo.

Second Mafia War and decline of the Ciaculli faction

By 1980, Michele Greco was considered by most to be no more than a "puppet" for Corleonesi boss Totò Riina. According to Tommaso Buscetta Michele Greco would just nod his head and agree with virtually everything Riina said during meetings between the heads of various Mafia families. Still, many families, such as the one led by Rosario Riccobono, wary of the looming war and wanting to maintain a neutral position, trusted their allegiance with Michele Greco and the Commission. According to Pentito Francesco Di Carlo, Stefano Bontade, Salvatore Inzerillo, Nicola Greco, Antonio Salamone of San Giuseppe Jato and Alfio Ferlito and Salvatore Pillera of Catania (who had succeeded Giuseppe Calderone) planned one last desperate move to avert the coming war by eliminating the top leadership of the Corleonesi, including Michele Greco himself and several other allies of Riina. According to Di Carlo, the plan involved luring Salvatore Riina and his deputy Giuseppe Giacomo Gambino to the Bontade estate, where they would be murdered, alongside an ambush against Bernardo Brusca of San Giuseppe Jato on the highway to Palermo, and a daring plan involving Nicola Greco, who was at that time a guest at the Favarella estate, unlocking the villa's doors at night to allow killers to enter and murder Michele Greco and other Corleonesi leaders sleeping there. However, the plan failed at the last minute due to traitors within the family of Stefano Bontade informing the Corleonesi beforehand, leading to Brusca to use a different road and Riina and Giacomo Gambino not to show up at the planned meeting. After some of the people who were supposed to sleep in the Greco estate on the night of the plot failed to show up, Nicola Greco is alleged to have hurriedly left the Favarella estate in the middle of the night in order to alert his men of the failure of the plan, and thereafter he fled back to Brazil and never returned to Sicily. Nonetheless, according to other pentiti such as Salvatore Contorno, there were no plans as such to kill off the Corleonesi leadership, and the fact they were only revealed after Bontade himself had been murdered shows that they were rumors deliberately spread around to retroactively justify the killings of Bontade and his allies.

The Second Mafia War began in earnest on 23 April 1981, when Stefano Bontade was murdered by the Corleonesi as he returned home from his birthday party. Over the following months and years, the Corleonesi would begin an unprecedented campaign of murder and destruction against all those Mafia families and members who were considered to have been close to Bontade, Inzerillo, Di Cristina, Calderone, Badalamenti and the Grecos of Ciaculli. Michele Greco immediately began spreading false information related to the origin of the conflict. For instance, when Rosario Riccobono arrived at the Favarella estate asking why Bontade had been killed, Greco stated that Bontade and people close to him had been plotting to kill Salvatore Riina, and invited Riccobono to help them in flushing out the remaining "scappati". In another conversation with Riccobono's men Salvatore Micalizzi and Gaspare Mutolo, Michele Greco blamed his cousin Salvatore "Cicchiteddu" Greco for starting the war, claiming he and his men had been plotting to replace Commission members with people loyal to them, even though Cicchiteddu had already been dead for years by then. During a meeting with the Interprovincial Commission, Greco stated that Bontade and Inzerillo had cheated the rest of the Mafia families of over 20 billion lire in drug trafficking proceedings. This was related to future pentito Antonino Calderone by the boss of Enna Giovanni Mungiovino, who also explained that Salvatore "The Engineer" Greco was in particular furious about the murders as they threatened to disrupt the entire drug trafficking operation run from Sicily. The Engineer, however, had no power to stop them, as he had long been operating from outside of Sicily by that time. Mungiovino himself would later be killed by the Corleonesi in 1983.

The one member of the Ciaculli Grecos who remained in Palermo, Giuseppe "Pinè" Greco, survived thanks to the intervention of his brother-in-law Antonio Salamone, who managed to secure his own as well as Greco's safe passage out of the country in the early days of the war, on the condition that they would never return to Sicily. Pinè Greco settled initially in Lazio, and after Tommaso Buscetta became a pentito, he too started giving information to the police in Rome about the operations of the Mafia, breaching the code of silence, omertà. Unlike Buscetta and Contorno, however, he was never formally registered as a pentito, and soon relocated to France. In retaliation for his cooperation, the Corleonesi would murder one of his closest associates, Giuseppe Romano, and later in 1989 they killed the baron Antonio D'Onufrio in Ciaculli, due to having been a friend of Pinè Greco and a suspected police informant himself.

Michele Greco either facilitated or organized several murders on behalf of Riina during the war, particularly when he convinced Stefano Bontade's deputy and successor, Mimmo Teresi, that there was no danger against him and that he should stop using the armored car that had formerly belonged to Bontade. Teresi was lured into an ambush and killed alongside three of his men several days later. Michele Greco's brother, Salvatore "The Senator", had a son named Giuseppe Greco, called "U Minnuni", who was a member of the infamous Corleonesi death squad that terrorized Palermo during the early 1980s, led by another Giuseppe Greco, nicknamed "Scarpuzzedda", who was also a man of honour from the family of Ciaculli but was not related by blood to the rest of the Greco clan. This death squad consisted of members from several different families and mandamentos, but many of the most prominent killers, including Scarpuzzedda, Mario Prestifilippo (Michele Greco's godson), Vincenzo Puccio and Giuseppe Lucchese all came from the Ciaculli-Croceverde Giardini families and answered directly to Michele Greco and Salvatore Riina. Lucchese in particular had been one of the shooters in the murder of Stefano Bontade.

One of the most infamous episodes of the war occurred shortly after Christmas 1982, when Giuseppe Greco "Scarpuzzedda", Riina's most important killer, was nearly killed himself in an assassination attempt by the losing faction in Palermo. The Corleonesi blamed two men close to Nicola Greco, Pinè Greco and Tommaso Buscetta for this attempted murder, Giovannello Greco and Giuseppe Romano, and retaliated immediately by killing many relatives of both men and of Buscetta. In January 1983, the Corleonesi began a forced mass eviction in the Ciaculli neighborhood of all men who were thought to be connected to Salvatore Greco "The Engineer", Nicola Greco and Pinè Greco. Dozens of families were forced to leave their homes under the threat of death; in particular, police recovered several letters sent to Francesco Bonaccorso, a nephew of "The Engineer", intimating him and his wife to immediately leave Ciaculli and never return, else they would be killed. The Corleonesi also ransacked and vandalized the homes of four members of the losing faction, including that of Pinè Greco and the defunct Salvatore Greco "Cicchiteddu". After this, the neighborhood of Ciaculli was cordoned off with metal grates, to prevent further infiltration by the "scappati" or by the police, but acts of violence and intimidation by the Corleonesi against the Ciaculli branch of the Grecos would continue, and in 1987 the house of Salvatore Greco "The Engineer" was burnt to the ground.

While the Ciaculli branch of the Grecos incurred few direct casualties during the war, owing to the fact that most of them had left Sicily prior to the start of the hostilities, their power was completely broken, and none of them ever returned to Sicily. Michele Greco and his brother Salvatore, originally from Croceverde-Giardini, thus took complete control of the Ciaculli family.

Decline of the Croceverde faction

While the Croceverde faction was at this point at the height of its power, in reality the Second Mafia War was also the beginning of the end for them. Michele and Salvatore Greco had accumulated immense power and influence within the organization thanks to their alliance with Riina, but this was not long-lasting. Many of their men soon started taking orders directly from Riina and Giuseppe Greco "Scarpuzzedda", and came to saw the two aging bosses as weak and irrelevant, and by the end of the war, Scarpuzzedda treated Michele Greco as a useless old man and acted as if he was the real boss of Ciaculli.[23] The downfall of the Croceverde Grecos, though, was ultimately due to their notoriety. Not only did they come from a long line of mafiosi, but their role within Cosa Nostra and the various meetings held over the years at the Favarella estate were well known to all members of the organization. Already in 1981, shortly after the murder of Stefano Bontade, one of his men, Salvatore Di Gregorio (brother of Stefano Di Gregorio, Bontade's driver), when interrogated by police after being arrested due to a theft, made several declarations and indicated Michele Greco as one of the top bosses of the organization. He was never able to confirm these statements in court because after he was released the Corleonesi murdered him via lupara bianca, but it was a sign of the times to come. In 1984, Tommaso Buscetta and Salvatore Contorno decided to cooperate with the authorities, followed afterwards by Antonino Calderone, and all three gave ample details of Michele and Salvatore Greco's involvement with the Mafia, their roles in many murders, and the way they used their estate and other properties to shield fugitives. Following this, the two brothers were forced to go into hiding due to an arrest warrant. Michele Greco was arrested on February 20, 1986, and joined the hundreds of defendants at the Maxi Trial. Greco gave testimony at the trial and to illustrate his standing as a supposedly honest citizen, he boasted of all the illustrious people he had entertained at his large estate, including a former chief prosecutor and police chiefs. Salvatore Greco "The Senator" remained in hiding until being arrested in 1991, by which point he had long stopped being an important figure within Cosa Nostra. The entire mandamento of Ciaculli came to be ruled by the Grecos' former underlings: Giuseppe Greco "Scarpuzzedda", Vincenzo Puccio and Giuseppe Lucchese.

Even their reign, though, would not last. Towards the end of 1985, Giuseppe Greco "Scarpuzzedda" vanished. He was murdered on the orders of Riina, who thought Scarpuzzedda was becoming too ambitious and independent-minded for his liking. Mario Prestifilippo, who was a great friend of Scarpuzzedda and also Michele Greco's godson, was himself killed in 1987. The families of Ciaculli and Croceverde-Giardini gradually lost power in favor of families that were much more closely allied to Riina, particularly the family of Resuttana controlled by Francesco Madonia, the family of San Lorenzo controlled by Giuseppe Giacomo Gambino and the family of the Noce controlled by Raffaele Ganci. Vincenzo Puccio, who became the leader following Scarpuzzedda's death, was ultimately murdered in prison in 1989 on the orders of Riina, followed shortly by his two brothers and several other accomplices such as Giuseppe Abbate, the boss of Roccella, who was a relative of Michele Greco. Giuseppe Lucchese would ultimately be arrested in 1990, after which the mandamento of Ciaculli would be dissolved and merged into Brancaccio with the leadership passing on.

Resized and restructured

By the 1990s, the Grecos were no longer part of the power structures of Cosa Nostra but restructured their organization to adapt to the new ways of organized crime. Their criminal presence emerged into Calabria in the late 1990s and with the turn of the new millennium, Interpol and FBI intel information showed that the reemergence of the Greco clan was strongly evident.[20]

The rising of new Commission

On 22 January 2019, all the new bosses of the new Commission were arrested by the police, including Leandro Greco, grandson of Michele Greco, also known as The Prince of The Pope.[8][24] Before his arrest, Leandro Greco had been appointed the capomandamento of Ciaculli, according to the authorities he has the mentality of an old man in the body of a young man.[25] Leandro Greco was subsequently subjected to the strict 41-bis prison regime, and the regent of the Ciaculli family became Giuseppe Greco "U Minnuni", the son of Salvatore "The Senator" Greco and Leandro Greco's cousin, who had been one of the members of the Corleonesi death squad during the 1980s mafia war. In 2021, Giuseppe Greco was arrested once again.[26]

References

- Lodato, Ho ucciso Giovanni Falcone, p. 53

- Lupo, History of the Mafia, p. 140

- (in Italian) Caruso, Da cosa nasce cosa, p. 84-86

- Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 254-59. Ermanno Sangiorgi, Questore (chief of police) of Palermo from 1898-1900 wrote a series of very comprehensive reports on Palermo's and the province's Mafia, formed by various groups, coordinated by a "conference among bosses" and headed by a "supreme boss", with details of criminal family structures, individual profiles, Mafia initiation rituals, codes of behaviour as well as it business methods and operations.

- Servadio, Mafioso, p. 178-79.

- Sterling, Octopus, p. 97-98.

- Lupo, History of the Mafia, p. 196-97

- "Mafia: inchiesta sulla Cupola, tra i fermati anche il nipote di Greco e il figlio di Lo Piccolo". ansa.it. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- (in Italian) Onesti, onestissimi praticamenti mafiosi Archived 2007-10-04 at the Wayback Machine, I Siciliani, April 1984

- (in Italian) L'organizzazione giudiziaria antimafia: una lunga battaglia Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, Gioacchino Natoli, February 19, 2005

- Lupo, History of the Mafia, p. 227

- Schneider & Schneider, Reversible Destiny, p. 62

- (in Italian) La Mafia vuole controllare il grande mercato di Palermo, La Stampa, August 20, 1956

- Sicilian Blood, Time, September 3, 1956

- Gambetta, The Sicilian Mafia, p. 112

- Lupo, History of the Mafia, p. 213

- The Rothschilds of the Mafia on Aruba, by Tom Blickman, Transnational Organized Crime, Vol. 3, No. 2, Summer 1997

- Servadio, Mafioso, p. 181.

- Schneider & Schneider, Reversible Destiny, p. 77-78

- Caruso, Da cosa nasce cosa, p. 487

- Stille, Excellent Cadavers, pp. 187-88

- Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 209

- Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 306

- amduemila-6. "Tra scappati e corleonesi così si riorganizza Cosa nostra". Antimafia Duemila (in Italian). Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "Mafia, fermato il nipote di Michele Greco: enfant prodige di Cosa nostra che voleva fare la guerra agli altri boss". Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian). 2019-01-22. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "Mafia, a Palermo comandano ancora i Greco: 16 arresti". Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian). 20 July 2021. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

Sources

- (in Italian) Caruso, Alfio (2000). Da cosa nasce cosa. Storia della mafia dal 1943 a oggi, Milan: Longanesi ISBN 88-304-1620-7

- Dickie, John (2004). Cosa Nostra. A history of the Sicilian Mafia, London: Coronet ISBN 0-340-82435-2

- Gambetta, Diego (1993).The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection, London: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-80742-1

- (in Italian) Lodato, Saverio (1999). Ho ucciso Giovanni Falcone. La confessione di Giovanni Brusca, Milan: Mondadori ISBN 88-04-55842-3

- Lupo, Salvatore (2009). History of the Mafia, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-13134-6

- Schneider, Jane T. & Peter T. Schneider (2003). Reversible Destiny: Mafia, Antimafia, and the Struggle for Palermo, Berkeley: University of California Press ISBN 0-520-23609-2

- Servadio, Gaia (1976). Mafioso. A history of the Mafia from its origins to the present day, London: Secker & Warburg ISBN 0-436-44700-2

- Sterling, Claire (1990), Octopus. How the long reach of the Sicilian Mafia controls the global narcotics trade, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-73402-4

- Stille, Alexander (1995). Excellent Cadavers. The Mafia and the Death of the First Italian Republic, New York: Vintage ISBN 0-09-959491-9

- (in Italian) Senato della Repubblica Italiana (1962). Indagine sui casi di singoli mafiosi, official government link

- (in Italian) Magistratura italiana e francese (1987). Interrogatorio di Antonino Calderone, official government link

- (in Italian) Bellavia, Enrico (2010). Un uomo d'onore, Rizzoli ISBN 9788817038959 (autobiography of pentito Francesco Di Carlo)

- (in Italian) Pennino, Gioacchino (2010). Il vescovo di Cosa Nostra, Sovera ISBN 978-8881245284 (autobiography of pentito Gioacchino Pennino Jr.)

External links

- (in Italian) Onesti, onestissimi, praticamenti mafiosi, I Siciliani", April 1984.