Greek–Yugoslav confederation

The Greek–Yugoslav confederation or Greek–Yugoslav federation,[a] or Balkan Union, was a political concept during World War II, sponsored by the United Kingdom and involving the Yugoslav government-in-exile and the Greek government-in-exile. The two governments signed an agreement pushing the proposal ahead, but it never got beyond the planning stage because of opposition from within the Yugoslav and the Greek governments, real world events, and the opposition of the Soviet Union. The proposal envisioned the creation of a confederation of Greece and Yugoslavia.

Background

Greece and Yugoslavia were both occupied by Axis powers and formed governments-in-exile in London.[1]

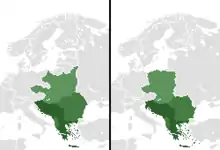

Establishment of the union was the first step of the British "Eden plan": its final aim was to create a central-eastern union that was friendly to the west. The next step was to include Albania, Bulgaria and Romania into a Balkan Union. The last step was to be folding of the Balkan Union with a Central European federation formed by Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland.[2] The first step was restricted to only Yugoslavia and Greece because they were the only countries that supported the Allies.[3]

Agreement

The two governments-in-exile negotiated the conditions of the agreement until the end of 1941. The agreement was signed by Slobodan Jovanović and Emmanouil Tsouderos[4] on the ceremony held in British Foreign Office, presided by the British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden. The agreement explicitly stated that both governments looked forward to accede other countries of the Balkans to the Union.[5] quoted in Wheeler (1980, pp. 157–8) Although caution was advised with revealing the hope that Bulgaria and Romania would join the union, on 4 February 1942, Eden stated in the House of Commons that the treaty signed between Yugoslavia and Greece was going to be a basis for the establishment of the Balkan confederation.[5]

Encouraged by the British Foreign Office, together with the Polish-Czechoslovak confederation, they were to form a pro-Western organisation of states between Germany and the Soviet Union.[1][6][7] Both governments-in-exile agreed to form a political, economic and military union, with the motto "The Balkans for the Balkan People".[1]

Their governments would not be unified but there would be much coordination between their respective parliaments and executives. Their respective monarchies were to be unified with the marriage of King Peter of Yugoslavia to Princess Alexandra of Greece.[1] The union was to be finalised after the war.[1]

The marriage of Peter and Alexandra proved to be a problematic move and reduced support for the union from both governments-in-exile.[1] On the international scene, the confederation was received favorably by Turkey but opposed by the Soviet Union, as Joseph Stalin saw no need for a strong and independent federation in Europe that could threaten his designs in Eastern Europe.[1][8][9][10]

Demise

In 1942, the British government decided to support Josip Broz Tito's forces instead of the Chetniks in Yugoslavia and rejected the plan as unworkable.[11] In 1944, the British withdrew their recognition for the Yugoslav government and recognised the communist Yugoslav National Committee of Liberation of Ivan Šubašić, who was subordinate to Tito.[1]

As the war ended, Yugoslavia shifted towards the communist camp, and the Greek Civil War started.[1]

With little support for the confederation from any existing powers, it was never realised, but it was briefly entertained in the form of a communist federation by some regional communist leaders, shortly after the war.[12]

Alternative plans

By the end of 1944, the Yugoslav Communist Party began the development of alternative plans for the establishment of a Balkan Federation. Because Churchill and Stalin agreed that Greece would be in the Western sphere of influence, the plans had to exclude Greece.[13]

See also

Notes

a ^ As the details of the planned union were never finalized, it is not clear whether it would be a federation or a confederation. Sources use both the term "Greek-Yugoslav federation" and the term "Greek-Yugoslav confederation".

References

- Jonathan Levy (6 June 2007). The Intermarium: Wilson, Madison, & East Central European Federalism. Universal-Publishers. pp. 203–205. ISBN 978-1-58112-369-2. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- Levy 2007, p. 203.

- Cahiers de Bruges, n.s. College d'Europe. 1971. p. 69. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

Only two countries, Yugoslavia and Greece, were in the Allied camp, which explains why practical plans of a regional Balkan confederation had to be restricted to them.

- Hidryma Meletōn Chersonēsou tou Haimou. Institute for Balkan Studies. 1964. p. 111. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

Negotiations lasting until the end of 1941 led to the conclusion of an agreement, signed on January 15, 1942, by Prime Ministers Tsouderos and Slobodan Jovanovid, concerning the establishment of a Balkan Union whose primary

- Kelly 2004, p. 132.

- Klaus Larres (2002). Churchill's Cold War: the politics of personal diplomacy. Yale University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-300-09438-1. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- Antoine Capet; Aïssatou Sy-Wonyu (2003). The "Special Relationship". Publication Univ Rouen Havre. p. 30. ISBN 978-2-87775-341-8. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- Jonathan Levy (6 June 2007). The Intermarium: Wilson, Madison, & East Central European Federalism. Universal-Publishers. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-58112-369-2. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- Walter Lipgens (1985). Documents on the history of European integration: Plans for European union in Great Britain and in exile, 1939–1945 (including 107 documents in their original languages on 3 microfiches). Walter de Gruyter. p. 648. ISBN 978-3-11-009724-5. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- Klaus Larres (2002). Churchill's Cold War: the politics of personal diplomacy. Yale University Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-300-09438-1. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- Kola 2003, p. 84.

- Geoffrey Roberts (2006). Stalin's wars: from World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. Yale University Press. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-300-11204-7. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- Kola 2003, p. 85.

Sources

- Briggs, A.; Meyer, E.; Thomson, David (2013). Patterns of Peacemaking. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-23257-2. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Kelly, George (2004). The Psychology of Personal Constructs: Volume One: Theory and Personality. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-48878-0. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Kola, Paulin (2003). The Search for Greater Albania. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-596-1. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Levy, Jonathan (2007). The Intermarium: Wilson, Madison, and East Central European Federalism. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58112-369-2. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Wheeler, Mark C. (1980). Britain and the war for Yugoslavia, 1940-1943. East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-914710-57-8.