Jean-Baptiste Greuze

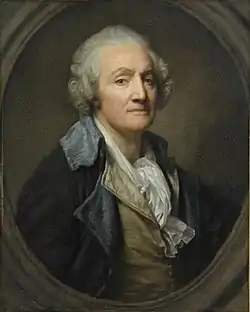

Jean-Baptiste Greuze (French pronunciation: [ʒɑ̃ batist ɡʁøz], 21 August 1725 – 4 March 1805) was a French painter of portraits, genre scenes, and history painting.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 August 1725 |

| Died | 4 March 1805 (aged 79) |

Biography

Early life

Greuze was born at Tournus, a market town in Burgundy. He is generally said to have formed his own talent; at an early age his inclinations, though thwarted by his father, were encouraged by a Lyonnese artist named Grandon, or Grondom, who enjoyed during his lifetime considerable reputation as a portrait-painter. Grandon not only persuaded Greuze's father to give way to his son's wishes, and permit the boy to accompany him as his pupil to Lyon, but, when at a later date he left Lyon for Paris, Grandon carried young Greuze with him.[1]

Settled in Paris, Greuze worked from the living model in the school of the Royal Academy, but did not attract the attention of his teachers; and when he produced his first picture, Le Père de famille expliquant la Bible a ses enfants, considerable doubt was felt and shown as to his share in its production. By other and more remarkable works of the same class Greuze soon established his claims beyond contest, and won the notice and support of the well-known connoisseur La Live de Jully, the brother-in-law of Madame d'Epinay. In 1755 Greuze exhibited his Aveugle trompé, upon which, presented by Pigalle the sculptor, he was immediately agréé by the Academy.[1]

Towards the close of the same year, he left France for Italy, in company with the Abbé Louis Gougenot. Gougenot had some acquaintance with the arts, and was highly valued by the Academicians, who, during his journey with Greuze, elected him an honorary member of their body on account of his studies in mythology and allegory; his acquirements in these respects are said to have been largely utilized by them, but to Greuze they were of doubtful advantage, and he lost rather than gained by this visit to Italy in Gougenot's company. He had undertaken it probably in order to silence those who taxed him with ignorance of great models of style, but the Italian subjects which formed the entirety of his contributions to the Salon of 1757 showed that he had been put on a false track, and he speedily returned to the source of his first inspiration.[1]

Relations with the Academy

In 1759, 1761 and 1763 Greuze exhibited with ever-increasing success; in 1765 he reached the zenith of his powers and reputation. In that year he was represented with at least thirteen works, amongst which may be cited La Jeune Fille qui pleure son oiseau mort, La Bonne Mère, Le Mauvais fils puni (Louvre) and La Malediction paternelle (Louvre). The Academy took occasion to press Greuze for his diploma picture, the execution of which had been long delayed, and forbade him to exhibit on their walls until he had complied with their regulations. "I have read the letter," said Diderot, "which is a model of honesty and reverence; I have seen Greuze's response, which is a model of vanity and impertinence: he should have backed it up with a masterpiece, and that's precisely what he didn't do."[2][1]

Greuze wished to be received as a historical painter and produced a work which he intended to vindicate his right to despise his qualifications as a genre artist. This unfortunate canvas (Sévère et Caracalla) was exhibited in 1769 side by side with Greuze's portrait of Jeaurat and his admirable Petite Fille au chien noir. The Academicians received their new member with all due honours, but at the close of the ceremonies the Director addressed Greuze in these words: "Sir, the Academy has accepted you, but only as a genre painter; the Academy has respect for your former productions, which are excellent, but she has shut her eyes to this one, which is unworthy, both of her and of you yourself."[3] Greuze, greatly incensed, quarrelled with his confreres, and ceased to exhibit until, in 1804, the Revolution had thrown open the doors of the Academy to all the world.[1]

In the following year, on 4 March 1805, he died in the Louvre in great poverty. He had been in receipt of considerable wealth, which he had dissipated by extravagance and bad management (as well as embezzlement by his wife) so that during his closing years he was forced to solicit commissions which his enfeebled powers no longer enabled him to carry out with success. "At the funeral of the long-neglected old man, a young woman deeply veiled and overcome with emotion plainly visible through her veil, laid upon the coffin, just before its removal, a bouquet of immortelles and withdrew to her devotions. Around the stem was a paper inscribed: "These flowers offered by the most grateful of his students are emblems of his glory. It was Mlle Mayer, later the friend of Prudhon."[4]

The brilliant reputation which Greuze acquired seems to have been due, not to his accomplishments as a painter – for his practice is evidently that current in his own day – but to the character of the subjects which he treated. That return to nature which inspired Rousseau's attacks upon an artificial civilization demanded expression in art.[1]

Legacy

Diderot, in Le Fils naturel and Père de famille, tried to turn the vein of domestic drama to account on the stage; that which he tried and failed to do, Greuze, in painting, achieved with extraordinary success, although his works, like the plays of Diderot, were affected by that very artificiality against which they protested. The touch of melodramatic exaggeration, however, which runs through them finds an apology in the firm and brilliant play of line, in the freshness and vigour of the flesh tints, in the enticing softness of expression, by the alluring air of health and youth, by the sensuous attractions, in short, with which Greuze invests his lessons of bourgeois morality.[1]

La Jeune Fille à l'agneau was bought at the Pourtal's sale in 1865 for at least a million francs. One of Greuze's pupils, Madame Le Doux, imitated with success the manner of her master; his daughter and granddaughter, Madame de Valory, also inherited some traditions of his talent. Madame de Valory published in 1813 a comédie-vaudeville, Greuze, ou l'accorde de village, to which she prefixed a notice of her grandfather's life and works, and the Salons of Diderot also contain, besides many other particulars, the story at full length of Greuze's quarrel with the Academy. Four of the most distinguished engravers of that date, Massard père, Flipart, Gaillard and Levasseur, were specially entrusted by Greuze with the reproduction of his subjects, but there are also excellent prints by other engravers, notably by Cars and Le Bas.[1]

Greuze was the father of painter Anna-Geneviève Greuze, who was also his pupil.[5]

Cultural references

In the second chapter of Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes story The Valley of Fear, Holmes' discussion of his enemy Professor Moriarty involves a Greuze painting in his possession, intended to illustrate Moriarty's wealth despite his small legitimate salary as an academic. A 1946 episode of the radio series The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes entitled "The Girl With the Gazelle" centers around the theft of a fictional Greuze painting of the same name, masterminded by Professor Moriarty.[6]

In the sixth part of The Leopard, a novel by the Italian writer Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, the Prince of Salina watches a Greuze painting, La Mort du Juste, and he starts thinking about death (as the "safety exit" which relieves older men of their anxieties) and judges that the pretty girls surrounding the dying man and the "disorder of their clothes suggested sex more than sorrow ... were the real subject of the picture."[7]

In the sixteenth chapter of E. M. Forster's novel Maurice, Clive mentions that he finds himself unable to approach Greuze's "subject matter" from anything more than purely aesthetic perspective, contrasting Greuze's work with that of Michelangelo in the process. In chapter 31, when Maurice visits Dr Barry, there are copies of Greuze on the walls.

Chinese author Xiao Yi mentions Greuze's work The Broken Pitcher throughout the first half of her novel Blue Nails. The Broken Pitcher is also mentioned in the first scene of the Jean-Paul Sartre play, The Respectful Prostitute.

Greuze is mentioned in the song "(We All Wear A) Green Carnation", Noël Coward's celebration of camp and queerness, from his 1929 operetta Bitter Sweet: "We believe in Art, / Though we’re poles apart / From the fools who are thrilled by Greuze. / We like Beardsley and Green Chartreuse. / (...) Faded boys, jaded boys, come what may, / Art is our inspiration / And as we are the reason for the “Nineties” being gay, / We all wear a green carnation."

Exhibitions

Edgar Munhall organized the first major exhibition devoted to the artist: "Jean-Baptiste Greuze, 1725-1805" (1976-1977).[8] The exhibition opened at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford and then traveled to the California Legion of Honor in San Francisco and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon.[9] In 2002, the first exhibition of Greuze's drawings was held at The Frick Collection in New York. It was also organized by Munhall, who wrote the catalog.[10]

Gallery

- Jean-Baptiste Greuze's works

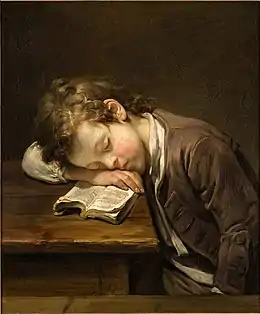

The Lazy Boy, 1755

The Lazy Boy, 1755 Mme Georges Gougenot de Croissy, née Vïrany de Varennes, 1757

Mme Georges Gougenot de Croissy, née Vïrany de Varennes, 1757_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Comte d'Angiviller, 1763

Comte d'Angiviller, 1763 W. A. Mozart, 1763–64. Yale University

W. A. Mozart, 1763–64. Yale University

The Father's Curse, 1770

The Father's Curse, 1770 Portrait of Count Stroganov as a Child, 1778

Portrait of Count Stroganov as a Child, 1778 Broken Eggs, 1756, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Broken Eggs, 1756, Metropolitan Museum of Art Cupid Crowned by Psyche, 1785-1790

Cupid Crowned by Psyche, 1785-1790 Jeanne Philiberte Ledoux, c. 1790

Jeanne Philiberte Ledoux, c. 1790.jpg.webp) Nicolas-Pierre-Baptiste Anselme, c. 1790

Nicolas-Pierre-Baptiste Anselme, c. 1790 The Two Friends, 18th-century

The Two Friends, 18th-century Young girl with blue ribbon, second half of 18th century[11]

Young girl with blue ribbon, second half of 18th century[11] Portrait of Marquise de Chauvelin, date unknown

Portrait of Marquise de Chauvelin, date unknown Le petit mathématicien or The young mathematician, date unknown

Le petit mathématicien or The young mathematician, date unknown The hermit or The distributor of rosaries, date unknown

The hermit or The distributor of rosaries, date unknown

References and sources

- References

- Chisholm 1911.

- "J'ai vu la lettre, qui est un modèle d'honnêteté et d'estime; j'ai vu la réponse de Greuze, qui est un modèle de vanité et d'impertinence: il fallait appuyer cela d'un chef-d'œuvre, et c'est ce que Greuze n'a pas fait."

- "Monsieur, l'Académie vous a reçu, mais c'est comme peintre de genre; elle a eu égard à vos anciennes productions, qui sont excellentes, et elle a fermé les yeux sur celle-ci, qui n'est digne ni d'elle ni de vous."

- Stranahan, C.H., ‘’A History of French Painting: An account of the French Academy of Painting, its salons, schools of instructions and regulations’’, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1896 p. 118

- Profile of Anne-Geneviève Greuze in the Dictionary of Pastellists Before 1800.

- Greenwald, Ken. "Sherlockian Story Summaries". Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Lampedusa, Guisseppe di, The Leopard, trans. by Archibald Colquhoun. New York: Pantheon Books, 2007, p. 227.

- Opperman, Hal N. (1979). "Review of Jean-Baptiste Greuze, 1725-1805 by Edgar Munhall." Eighteenth-Century Studies 12/3, pp. 409-13.

- Kramer, Hilton (2002). "Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Domestic Draftsman, A Man Out of Time". Observer, 3 June. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Munhall, Edgar (2002). Greuze the Draftsman. The Frick Collection, New York, May 14 - August 4, 2002.

- "Jeune fille au ruban bleu". POP : la plateforme ouverte du patrimoine. Ministère de la Culture (France). Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- Sources

- Normand, J. B. Greuze (1892).

- Munhall, Edgar. Jean-Baptiste Greuze, 1725-1805 (1976).

- Emma Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). ISBN 0-521-55508-6.

- Gillet, Louis (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Greuze, Jean Baptiste". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

![]() Media related to Jean-Baptiste Greuze at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jean-Baptiste Greuze at Wikimedia Commons

- 68 artworks by or after Jean-Baptiste Greuze at the Art UK site

- Works and literature at PubHist

- Europe in the age of enlightenment and revolution, a catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Greuze (see index)