Grímsvötn

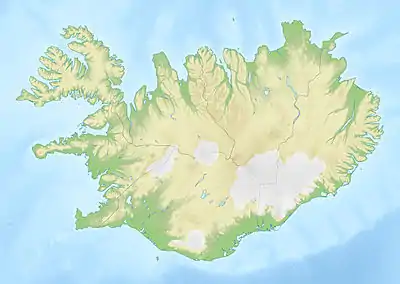

Grímsvötn (Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈkrimsˌvœhtn̥];[2] vötn = "waters", singular: vatn) is an active volcano with a (partially subglacial) fissure system located in Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland. The volcano itself is completely subglacial and located under the northwestern side of the Vatnajökull ice cap. The subglacial caldera is at 64°25′N 17°20′W, at an elevation of 1,725 m (5,659 ft). Beneath the caldera is the magma chamber of the Grímsvötn volcano.

| Grímsvötn | |

|---|---|

Grímsvötn and the Vatnajökull glacier, Iceland, July 1972 | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,725 m (5,659 ft)[1] |

| Listing | List of volcanoes in Iceland |

| Coordinates | 64°25′12″N 17°19′48″W |

| Geography | |

Grímsvötn Austur-Skaftafellssýsla / Vestur-Skaftafellssýsla, Iceland | |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Volcanic caldera |

| Last eruption | May 2011 |

Grímsvötn is a basaltic volcano which has the highest eruption frequency of all the volcanoes in Iceland and has a southwest-northeast-trending fissure system. The massive climate-impacting Laki fissure eruption of 1783–1784 was a part of the same fissure system. Grímsvötn was erupting at the same time as Laki during 1783, but continued to erupt until 1785. Because most of the volcanic system lies underneath Vatnajökull, most of its eruptions have been subglacial and the interaction of magma and meltwater from the ice causes phreatomagmatic explosive activity.[3]

Jökulhlaup

Eruptions in the caldera regularly cause glacial outbursts known as jökulhlaup.[4] Eruptions melt enough ice to fill the Grímsvötn caldera with water, and the pressure may be enough to suddenly lift the ice cap, allowing huge quantities of water to escape rapidly. Consequently, the Grímsvötn caldera is monitored very carefully.

When a large eruption occurred in 1996, geologists knew well in advance that a glacial burst was imminent. It did not occur until several weeks after the eruption finished, but monitoring[5] ensured that the Icelandic ring road (Hringvegur) was closed when the burst occurred. A section of road across the Skeiðará sandur was washed away in the ensuing flood, but no one was hurt.

Eruption history between 1990 and today

Gjálp 1996

(See also the main article: 1996 eruption of Gjálp

The Gjálp fissure vent eruption in 1996 revealed that an interaction may exist between Bárðarbunga and Grímsvötn. A strong earthquake in Bárðarbunga, about 5 on the Richter scale, is believed to have started the eruption in Gjálp. On the other hand, because of the magma erupted showed strong connections to the Grímsvötn Volcanic System acc. to petrology studies, the 1996 as well as a former eruption there in the 1930s are thought to have taken place within Grímsvötn Volcanic system.[6][7]

1998 and 2004 eruptions

A week-long eruption occurred at Grímsvötn starting on 28 December 1998, but no glacial burst occurred. In November 2004, a week-long eruption occurred. Volcanic ash from the eruption fell as far away as mainland Europe and caused short-term disruption of airline traffic into Iceland, but again no glacial burst followed the eruption.

2011 eruption

Harmonic tremors were recorded twice around Grímsvötn on 2 and 3 October 2010, possibly indicating an impending eruption.[8] At the same time, sudden inflation was measured by GPS in the volcano, indicating magma movement under the caldera. On 1 November 2010 meltwater from the Vatnajökull glacier was flowing into the lake, suggesting that an eruption of the underlying volcano could be imminent.

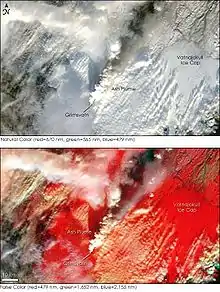

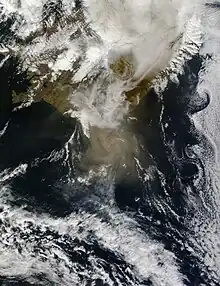

On 21 May 2011 at 19:25 UTC, an eruption began, with 12 km (7 mi) high plumes accompanied by multiple earthquakes,[9][10][11][12] Until 25 May, the eruption scale had been larger than that of the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull.

The ash cloud from the eruption rose to 20 km (12 mi), and was so far 10 times larger than the 2004 eruption, and the strongest in Grímsvötn in the last 100 years.[13]

Disruption to air travel in Iceland[14] commenced on 22 May, followed by Greenland, Scotland,[15] Norway, Svalbard[16] and a small part of Denmark on subsequent days. On 24 May the disruption spread to Northern Ireland and to airports in northern England.[14] The cancellation of 900 out of 90,000 European flights[17] in the period 23–25 May was much less widespread than the 2010 disruption after the Eyjafjallajökull eruption.

The eruption stopped at 02:40 UTC on 25 May 2011, although there was some explosive activity from the eruptive vents affecting only the area around the crater.[18][19][20]

2020-21 threats of eruption

In June 2020, the Icelandic Meteorological Office (IMO) issued a warning that an eruption might take place in the coming weeks or months, following scientists reporting high levels of sulfur dioxide, which is indicative of the presence of shallow magma. IMO warned that a glacial flood as a result of melting ice could trigger an eruption.[21] No eruption occurred.

In September 2021, an increase in water outflow from under the Vatnajökull ice cap was reported. The water contains elevated levels of dissolved hydrogen sulfide, suggesting increased volcanic activity under the ice.[22] Jökulhlaup (glacial lake flooding) can occur before or after an eruption.

On 4 December 2021, a jökulhlaup occurred from Grímsvötn into the Gígjukvísl river, with an average flow of 2600 m3/s. Two days later, the Icelandic Meteorological Office increased the alert level for Grímsvötn from yellow to orange, after a series of earthquakes was detected. On 7 December, the alert level was lowered back to yellow, after seismic activity decreased and no signs of eruptive activity were detected.

Bacteria in the subglacial lakes

In 2004, a community of bacteria was detected in water of the Grímsvötn lake under the glacier, the first time that bacteria have been found in a subglacial lake. The lakes never freeze because of the volcanic heat. The bacteria can also survive at low concentrations of oxygen. The site is a possible analogue for life on the planet Mars, because there are also traces of volcanism and glaciers on Mars and thus the findings could help identify how to look for life on Mars.[23][24]

Future trends

Studies indicate that volcanic activity in Iceland rises and falls so that the frequency and size of eruptions in and around the Vatnajökull ice cap varies with time. It is believed that the four eruptions between 1996 and 2011 could mark the beginning of an active period, during which an eruption in Grímsvötn in Vatnajökull may be expected every 2–7 years. Parallel volcanic activity in nearby Bárðarbunga is known to be associated with increased activity in Grímsvötn. Seismic activity has been increasing in the area in recent years, indicating the entry of magma.[25]

See also

References

- "Grímsvötn". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 15 August 2006.

- "How to pronounce /grímsvötn/". youtube.com. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- Jude-Eton, T. C.; Thordarson, T.; Gudmundsson, M. T.; Oddsson, B. (2012-03-08). "Dynamics, stratigraphy and proximal dispersal of supraglacial tephra during the ice-confined 2004 eruption at Grímsvötn Volcano, Iceland". Bulletin of Volcanology. 74 (5): 1057–1082. Bibcode:2012BVol...74.1057J. doi:10.1007/s00445-012-0583-3. ISSN 0258-8900. S2CID 128678427.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2011-05-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Jökulhlaup figure 8.1 - Russell, Andrew J.; Gregory, Andrew R.; Large, Andrew R. G.; Fleisher, P. Jay; Harris, Timothy D. (2007). "Tunnel channel formation during the November 1996 jökulhlaup, Skeiðarárjökull, Iceland". Annals of Glaciology. 45 (1): 95–103. Bibcode:2007AnGla..45...95R. doi:10.3189/172756407782282552.

- See eg.: Elín Margrét Magnúsdóttir: Gjóska úr Grímsvötnum 2011 og Bárðarbungu 2014-2015 : Ásýndar- ogkornastærðargreining. BS ritgerð. Jarðvísindadeild Háskóli Íslands (2017) (in Icelandic, abstract also in English) Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- See also: Anne Schöpa: Subglacial volcanism with examples from Iceland. TU Freiberg. (2008)

- "Possible Harmonic tremor pulse at Grímsfjall volcano | Iceland Volcano and Earthquake blog". Jonfr.com. 2010-10-02. Archived from the original on 2010-10-10. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- Eldgos í Grímsvötnum Archived 2011-08-03 at the National and University Library of Iceland, 24 May 2011 (in Icelandic)

- Njörður Helgason (14 April 2011). "Vegurinn um Skeiðarársand lokaður". mbl.is. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- "Iceland's most active volcano erupts – Europe". Al Jazeera English. 21 May 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- "Iceland volcanic eruption 'not linked to the end of the world' | IceNews – Daily News". Icenews.is. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- "Largest Volcanic Eruption in Grímsvötn in 100 Years". Daily News. Iceland Review Online. 22 May 2011. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- Eurocontrol news

- Scottish flights grounded by Iceland volcanic ash cloud, BBC, 23 May 2011

- Iceland eruption hits Norwegian flights, The Foreigner, 23 May 2011

- David Learmount (26 May 2011). "European proceedures (sic) cope with new ash cloud". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- "Volcanic Ash Advisory at 1241 on 25 May 2011". Met Office UK. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- "Iceland volcano ash: German air traffic resuming". BBC News. 25 May 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- "Update on volcanic activity in Grímsvötn". Iceland Met Office. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- "Evidences that Grímsvötn volcano is getting ready for the next eruption | News". Icelandic Meteorological office. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- "Grimsvötn volcano (Iceland): subglacial meltwater flood in progress". Volcano Discovery. 3 September 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- Gaidos, E; Lanoil, B; Thorsteinsson, T; Graham, A; Skidmore, M; Han, SK; Rust, T; Popp, B (2004). "A viable microbial community in a subglacial volcanic crater lake, Iceland". Astrobiology. 4 (3): 327–44. doi:10.1089/1531107041939529. PMID 15383238.

- Peplow, Mark (2004). "Glacial lake hides bacteria". Nature. doi:10.1038/news040712-6.

- "Icelandic Met Office on 1 September 2011". Icelandic Met Office. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

External links

- Grímsvötn Archived 2017-02-04 at the Wayback Machine in the Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes

- Update on Grímsvötn Activity – from the Icelandic Met Office and University of Iceland (updated at least daily)

- Current seismology around Grímsvötn – Earthquakes in last 48 hours

- BBC news report of the 23 May 2011 eruption

- Report on the 2011 start of the Grímsvötn eruption from the Icelandic Met Office

- Official Website of Vatnajökull National Park