Grind (musical)

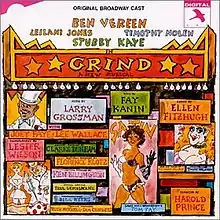

Grind is a 1985 musical with music by Larry Grossman, lyrics by Ellen Fitzhugh, and a book by Fay Kanin. Grind is a portrait of a largely African-American burlesque house in Chicago in the Thirties.

| Grind | |

|---|---|

| A New Musical | |

Original Broadway Cast Recording | |

| Music | Larry Grossman |

| Lyrics | Ellen Fitzhugh |

| Book | Fay Kanin |

| Productions | 1985 Broadway |

Reviews of the production were mixed at best. In his The New York Times review, Frank Rich wrote: "...the show has become a desperate barrage of arbitrary musical numbers, portentous staging devices, extravagant costumes..., confused plot twists and sociological bromides..."[1]

Grind eventually closed after a run of slightly more than two months, losing its entire $4.75 million investment. It was one of a string of six Broadway flops directed by Hal Prince in the 1980s, and Prince and three other members of the creative team were suspended by the Dramatists Guild for signing a "substandard contract."[2]

In a Broadway season described by theater historian Ken Mandelbaum as "dismal" for new musicals,[3] Grind was nominated for seven Tony Awards, including Best Musical; it eventually won two, for Best Featured Actress in a Musical (Leilani Jones) and Best Costume Design (Florence Klotz).

Plot

The Prologue

The singers, dancers, comedians, and strippers who make up the ensemble of Harry Earle's Burlesque take the stage and welcome the audience (“This Must Be the Place”). The year is 1933 and the city is Chicago. We are introduced to the white characters: HARRY EARLE, the owner of the venue; his wife, ROMAINE, who is a stripper; and the lead white comedians, SOLLY and GUS. We are also introduced to the black characters: LEROY, the lead black comedian; SATIN, who is also a stripper; and MAYBELLE, the wardrobe lady for the black performers.

Act One

Backstage, the color lines are harshly drawn: The white performers congregate in one dressing room, while the black performers congregate in another. Black and white performers do not perform together onstage during the various acts, as dictated by the local authorities.

Leroy, a known playboy who has had affairs with many of the black chorus girls, flirts with Satin and orders ribs for the women. Harry interviews LINETTE, who is applying to become one of the black chorus girls. In a private moment, Gus confesses to Solly that he's been losing his eyesight. Solly assures that Gus that as long as the routines go well, no one will notice.

Onstage, Gus performs a hospital sketch with Romaine (who plays a sexy nurse) and an actor referred to as The Stooge (“Cadaver”). The sketch goes awry when Gus accidentally sticks The Stooge with a prop needle, which causes the actor to quit the show. Gus tries to brush off the incident, but Harry is quick to point out that this is the third “Stooge” to quit in two weeks. Satin goes onstage to perform a strip routine (“A Sweet Thing Like Me”).

Gus, unable to find a replacement sketch partner, enters the alley outside the venue so he can think (“I Get Myself Out”). In a moment of desperation, he enlists DOYLE, one of the many homeless men who reside in the alley. Doyle is drunk and doesn't speak, but Gus moves forward.

Inside the venue, Harry speaks with DIX, a neighborhood cop. Dix is assured that none of the performers are violating color lines and is invited to take a look around to ensure this fact. Gus introduces Doyle to Harry, who rejects the bum outright. Nevertheless, Gus tells Doyle to wait for him in his dressing room. Doyle, confused and unfamiliar with the venue, walks upstairs to the black dressing room.

Leroy arrives with ribs and continues to flirt with Satin, who has been unsettled by the appearance of Dix. Leroy assures her and the black chorus girls that everything will be fine (“My Daddy Always Taught Me to Share”). When he goes upstairs to the black dressing room, Leroy is surprised to find Doyle waiting. He leads the stranger downstairs to the white dressing room and offers him a bottle of whiskey, which Doyle eagerly accepts. Gus, Solly, and Romaine desperately try to sober Doyle up in time for his first performance.

In the alley, Satin meets with her kid brother, GROVER. Satin has been giving Grover money she's earned to help their mother, MRS. OVETHA FAYE. Mrs. Faye, who appears in the alley, makes it clear that she does not want her daughter's money, as it has been earned working at the burlesque venue. Mrs. Faye exits with Grover, leaving Satin to fume. Leroy tries to comfort her, though she assumes it is yet another pass. She reveals her true name (Laticia) and insists that the woman Leroy sees onstage every night is not the woman he'd be bringing home. When she eventually settles down, it will be with the kind of man “they don’t make anymore” (“All Things To One Man”. Leroy, taken aback by her display of emotion, makes a joke before heading onstage. During his routine (“The Line”), Leroy despairs over his inability to be serious when the moment counts.

Gus and Doyle, having managed to squeak through their first performance, exit into the alley. When Gus tries to worm his way out of paying Doyle, the latter lashes out. Gus begs Doyle to return the next day so that they may continue working together. Doyle, left alone, begins to sing to an unseen wife and son (“Katie, My Love”). He secretly longs to die so that he may be with them. Satin asks if he's okay, to which Doyle replies, “I could tell you I’m feelin’ no pain, ma’am - but I'd be lyin’.”

The next morning, the performers slowly enter as Gus waits for Doyle’s arrival. The company sings (“Rise and Shine”), with the performers complaining and Maybelle encouraging them to do their best. We see Satin discussing a bike with Leroy over the phone. Gus is delighted to find a newly shaven, cleanly dressed Doyle waiting in the dressing room. Leroy enters with a new bike that he and Satin plan to give to Grover on his 10th birthday. When it's revealed that Leroy doesn't know how to ride a bike, Doyle offers to ride it to Grover's home (“Yes Ma’am”). Leroy and Satin mock Mrs. Faye as they head to the south side of Chicago (“Why Mama Why”).

At Mrs. Faye's home, Satin and Leroy arrive just as Doyle coasts in on Grover's new bike. They present an upside down cake prepared by Romaine but Mrs. Faye, incensed, denounces the party so that she may focus on her ironing. Doyle tells a story about his childhood that transfixes the group, including Mrs. Faye. The old woman ultimately joins in as Grover blows out his birthday candles.

Doyle helps Grover learn how to ride his bike. A quartet of white PUNKS confront the group and destroy the bike, calling Doyle a “n***er lover”. Leroy is unable to process the situation and escapes into the first act's closing number (“This Crazy Place”). Satin protests but ultimately gives into the performance, assuring Leroy that what they've just experienced was nothing more than a dream.

Act Two

The next day, Linette expresses concern that she won't be ready for her next number. The performers reassure her that, no matter what they do onstage, it doesn't matter so long as they're undressed “From The Ankles Down”.

Satin gives Romaine a note from Grover, thanking her for his birthday cake. Though she is reluctant to accept, Satin agrees to sit in the white dressing room with Romaine and talk about the birthday party. She is unable to reveal exactly what happened on that day. Leroy shows up with a receipt for a replacement bike but Satin rejects his offer, insisting that he can't “keep smilin’ everything away”. Romaine enters the black dressing room to talk to Leroy and encourage him to keep trying with Satin. When Harry sees his wife exiting the black dressing room, he reminds her that they could be shut down for such a violation.

Gus introduces a juggling routine to Doyle but is infuriated when his eyesight prevents him from juggling properly. Doyle suggests that they incorporate his mistakes into the act. As they create this revised routine, Satin watches from afar (“Who Is He?”). Gus notices that Doyle is taking notes and insists that a true performer should “Never Put It In Writing”. Doyle gets it (“I Talk, You Talk”) and the three performers come together for a big finish. Satin flinches when she realizes Doyle is holding her arm.

When Gus and Doyle perform their juggling act onstage, it ends with Gus accidentally walking off the stage and becoming enveloped in the stage works. Harry declares that Gus is no longer fit to work at the venue. Doyle promises to help his new partner, seeing as Gus was the one to pull him out of the alley and give him a reason for living. Gus tries to appear cheerful but sings a mournful reprise of “I Get Myself Out” when left alone.

Romaine and Solly perform a comedy routine (“Timing”) when a gunshot is heard backstage. Harry appears before the audience to report that an accident has occurred and the show has been cancelled. Doyle is shown standing next to a funeral wreath as Maybelle and the company mourn the death of Gus (“These Eyes of Mine”).

Leroy and Satin arrive backstage on a Sunday, having been unable to locate Doyle, who has gone missing since the funeral. Leroy takes a moment to clarify that he doesn't view Satin as a one-time girl. He wants to be with her permanently, if she'll have him. Satin is lost in thought and states that she'll need time to think about Leroy's offer. Despite this, Leroy believes he's on the right track and privately claims victory (“New Man”). Satin realizes that the only spot she hasn't checked is the alley and is horrified to find a drunken Doyle being beaten by STREET TOUGHS. She barely manages to pry Doyle out of their grip by threatening to call the cops.

Doyle is taken to Satin's apartment, where he drunkenly calls out for his dead wife and son. Sitting up in bed, he catatonically reveals how, when he was living in Ireland, he made a bomb intended to kill British soldiers on a train. It was only after the explosion that Doyle learned his wife and son were on that same train ("Down"). He collapses, and the next morning he reveals to Satin that his real name is Thomas. They kiss, and when Satin opens her door to leave for work she is met with the sight of two cartons of ribs. She and Doyle realize that Leroy must have been outside the entire time.

Onstage, Leroy sings about Chicago and “A Century of Progress”. The chorus girls appear onstage with Satin and Leroy proceeds to humiliate her, ripping off her wig and g-string in front of the audience. Satin escapes to her dressing room and is confronted by Leroy, who slaps her. He gets into a fight with Doyle that highlights the color line and causes the company to fight amongst themselves. Henry intervenes and demands that everyone get back to work.

Satin appears onstage to sing another rendition of “A Sweet Thing Like Me”. She is interrupted by the Street Toughs, who throw tomatoes at her until she is led offstage by the Stage Manager. Doyle confronts the Street Toughs and the Company spills onto the stage to help fend them off. The group freezes in a moment of stylized theatricality so that Leroy and Satin can be shown backstage. They make amends and Leroy vows to help her in any way that he can, even if they can't be together. The Street Toughs are defeated and the company triumphantly crosses the color barrier, vowing that they won't be segregated moving forward. Leroy, Satin, and Doyle are shown arm in arm once more (“This Must Be the Place - Reprise”).

Musical numbers

|

|

Production history

In the mid-1970s, writer Fay Kanin wrote a screenplay entitled This Must Be the Place, which was set in a 1930s Chicago burlesque house that featured black and white performers; however, the screenplay was never produced.[4] In 1982, she approached Hal Prince with the idea of doing the screenplay's story as a musical, to which Prince enthusiastically agreed.

Kanin wrote the musical's book; the music was by Larry Grossman, who had written the score for Prince's previous Broadway musical, 1982's A Doll's Life,[5] and the lyrics were by Ellen Fitzhugh, who had written lyrics for Off-Broadway musicals such as 1984's Diamonds (directed by Prince) and 1982's Herringbone.[6]

During pre-production, the show was titled Century of Progress.[7]

According to New York Daily News columnist Douglas Watt, the show was in "serious trouble" during its out-of-town tryout in Baltimore.

A number of songs were taken out of the show during its tryout and New York previews, including "The Best," "La Salle Street Stomp," "The One I Want is Always on the Bottom," "Rabbity Stew" (which was eventually incorporated into Grossman's 1993 musical Paper Moon), "Rise and Shine" (whose music was eventually incorporated into the title song), and "You, Pasha, You".[7]

At one point, Bob Fosse was brought on to choreograph "New Man" for Ben Vereen.[7]

Broadway production

Grind opened on Broadway at the Mark Hellinger Theatre on April 16, 1985 and closed on June 22, 1985 after 71 performances and 25 previews.[8]

The musical was directed by Hal Prince (who was also one of the producers), with set design by Clarke Dunham, costume design by Florence Klotz, lighting design by Ken Billington, musical direction by Paul Gemignani, orchestrations by Bill Byers, additional orchestrations by Jim Tyler and Harold Wheeler, dance music arrangements by Tom Fay, dance music for New Man arranged by Gordon Harrell, with choreography by Lester Wilson, assistant choreography by Larry Vickers, and hair and make up by Richard Allen.[8]

The cast included Ben Vereen (Leroy), Stubby Kaye (Gus), Lee Wallace (Harry), Joey Faye (Solly), Marion Ramsey (Vernelle), Hope Clarke (Ruby), Valarie Pettiford (Fleta), Candy Brown (Kitty), Wynonna Smith (Linette), Carol Woods (Maybelle), Sharon Murray (Romaine), Brian McKay (Louis, the Stage Manager), Oscar Stokes (Mike, the Doorman), Leonard John Crofoot, Timothy Nolen (Doyle), Donald Acree (Grover), Ruth Brisbane (Mrs. Faye) and Leilani Jones (Satin the stripper). Knockabouts, Bums, and Toughs portrayed by Leonard John Crofoot, Ray Roderick, Kelly Walters, Steve Owsley, Malcolm Perry.[8]

Awards and nominations

Original Broadway production

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Tony Award | Best Musical | Nominated | |

| Best Book of a Musical | Fay Kanin | Nominated | ||

| Best Original Score | Larry Grossman and Ellen Fitzhugh | Nominated | ||

| Best Performance by a Featured Actress in a Musical | Leilani Jones | Won | ||

| Best Direction of a Musical | Harold Prince | Nominated | ||

| Best Scenic Design | Clarke Dunham | Nominated | ||

| Best Costume Design | Florence Klotz | Won | ||

| Drama Desk Award | Outstanding Featured Actor in a Musical | Timothy Nolen | Nominated | |

| Outstanding Featured Actress in a Musical | Leilani Jones | Won | ||

| Sharon Murray | Nominated | |||

| Outstanding Orchestrations | Bill Byers | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Lyrics | Ellen Fitzhugh | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Music | Larry Grossman | Won | ||

| Outstanding Set Design | Clarke Dunham | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Lighting Design | Ken Billington | Nominated | ||

| Theatre World Award | Leilani Jones | Won | ||

References

- Rich, Frank. "Stage. Grind from Harold Prince" The New York Times, April 17, 1985

- McKinley, Jesse. "On Stage and Off" The New York Times, May 17, 2002

- Mandelbaum, Ken. "Tony's Best Musicals---Part Three" broadway.com, May 24, 2004

- Mandelbaum, Ken. Grind Not Since Carrie: Forty Years of Broadway Musical Flops, St. Martin's Press, 1992, ISBN 1-466843276, pp. 317 - 321

- "Larry Grossman Broadway" ibdb.com, accessed August 27, 2019

- "Ellen Fitzhugh Theatre" Internet Off-Broadway database, accessed August 27, 2019

- Dietz, Dan. Grind The Complete Book of 1980s Broadway Musicals, Rowman & Littlefield, 2016, ISBN 1-442260920, pp 239-241

- " Grind Broadway" Playbill vault, accessed August 27, 2019

External links

- Grind at the Internet Broadway Database

- plot and other information at rationalmagic

- "Production: Grind" April 1985 American Theatre Wing, April 1985, accessed August 27, 2019