Gulf Cartel

The Gulf Cartel (Spanish: Cártel del Golfo, Golfos, or CDG)[6][7] is a criminal syndicate and drug trafficking organization in Mexico,[8] and perhaps one of the oldest organized crime groups in the country.[9] It is currently based in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, directly across the U.S. border from Brownsville, Texas.

Cártel del Golfo | |

Logo of the Gulf Cartel | |

| Founded | 1930s |

|---|---|

| Founded by | Juan Nepomuceno Guerra, Juan García Ábrego |

| Founding location | Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico |

| Years active | 1930s−present |

| Territory | Mexico: Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí, Veracruz, Jalisco, the U.S. states of Texas, Louisiana, and Georgia |

| Ethnicity | Majority Mexican Mexican-American, minority Guatemalan |

| Criminal activities | Drug trafficking, money laundering, extortion, kidnapping, human trafficking, people smuggling, robbery, murder, arms trafficking, bribery, fencing, counterfeiting |

| Allies | Medellín Cartel (defunct) Cali Cartel (defunct) Los Mexicles (current status unknown) Narcosatanists[1][2] (defunct) Camorra[3] 'Ndrangheta Serbian mafia[4][3] Jalisco New Generation Cartel |

| Rivals | Los Zetas Juárez Cartel Guadalajara Cartel (defunct) Sinaloa Cartel[5] (starting in 2021) La Familia Michoacana Beltrán-Leyva Cartel Tijuana Cartel Los Negros (disbanded) Cártel del Noreste |

Their network is international, and is believed to have dealings with crime groups in Europe, West Africa, Asia, Central America, South America, and the United States.[10][11] Besides drug trafficking, the Gulf Cartel operates through protection rackets, assassinations, extortions, kidnappings, and other criminal activities.[12] The members of the Gulf Cartel are known for intimidating the population and for being particularly violent.[13]

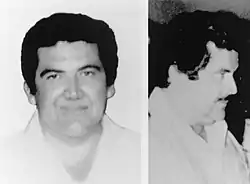

Although its founder Juan Nepomuceno Guerra smuggled alcohol in large quantities to the United States during the Prohibition era, and heroin for over 40 years,[14] it was not until the 1980s that the cartel was shifted to trafficking cocaine, methamphetamine and marijuana under the command of Juan Nepomuceno Guerra and Juan García Ábrego.

History

Foundation: 1930s–1980s

The Gulf Cartel, a drug cartel based in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico, was founded in the 1930s by Juan Nepomuceno Guerra.[15][16] Originally known as the Matamoros Cartel (Spanish: Cártel de Matamoros),[17] the Gulf Cartel initially smuggled alcohol and other illegal goods into the U.S.[16] Once the Prohibition era ended, the criminal group controlled gambling houses, prostitution rings, a car theft network, and other illegal smuggling.[18] It grew significantly in the 1970s under the leadership of kingpin Juan García Ábrego.[16]

García Ábrego era (1980s–1990s)

By the 1980s, García Ábrego began incorporating cocaine into the drug trafficking operations and started to have the upper hand on what was now considered the Gulf Cartel, the greatest criminal dynasty in the US-Mexico border. By negotiating with the Cali Cartel,[19] García Ábrego was able to secure 50% of the shipment out of Colombia as payment for delivery, instead of the US$1,500 per kilogram they were previously receiving. This renegotiation, however, forced Garcia Ábrego to guarantee the product's arrival from Colombia to its destination. Instead, he created warehouses along the Mexican's northern border to preserve hundreds of tons of cocaine; this allowed him to create a new distribution network and increase his political influence. In addition to trafficking drugs, García Ábrego would ship cash to be laundered, in the millions.[20] Around 1994, it was estimated that the Gulf Cartel handled as much as "one-third of all cocaine shipments" into the United States from the Cali Cartel suppliers.[21] During the 1990s, the PGR (Procuraduría General de la República), the Mexican attorney general's office, estimated that the Gulf Cartel was "worth over US$10 billion."[22]

Corruption in the United States

García Ábrego's ties extended beyond the Mexican government corruption and into the United States. With the arrest of one of García Ábrego's traffickers, Juan Antonio Ortiz, it became known the cartel would ship tons of cocaine in the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) buses between the years of 1986 to 1990. The buses made great transportation, as Antonio Ortiz noted since they were never stopped at the border.[23]

It also became known that, in addition to the INS bus scam, García Ábrego had a "special deal" with members of the Texas National Guard who would truck tons of cocaine and marijuana from South Texas to Houston for the cartel.[23]

Garcia Abrego's reach became known when a United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent named Claude de la O, in 1986, stated in testimony against García Ábrego that he received over US$100,000 in bribes and had leaked information that could have endangered an FBI informant as well as Mexican journalists. In 1989 Claude was removed from the case for unknown reasons, retiring a year later. García Ábrego bribed the agent in an attempt to gather more information on U.S. law enforcement operations.[24][25]

Arrest of Ábrego

García Ábrego's business had grown to such length that the FBI placed him on the Top Ten Most Wanted in 1995. He was the first drug trafficker to be on that list.[26] On 14 January 1996, García Ábrego was arrested outside a ranch in Monterrey, Nuevo León.[27] He was quickly extradited to the United States where he stood trial eight months after his arrest. García Ábrego was convicted for 22 counts of money laundering, drug possession and drug trafficking.[28] Jurors also ordered the seizure of $350 million of García Ábrego's assets — $75 million more than what was previously planned.[29] Juan García Ábrego is currently serving 11 life terms in a maximum security prison in Colorado, U.S.[30] In 1996, it was disclosed that García Ábrego's organization paid millions of dollars in bribes to politicians and law enforcement officers for his protection. It was later proven after his arrest that the deputy attorney general in charge of Mexico's federal Judicial Police had accumulated more than US$9 million for protecting García Ábrego.[31]

García Ábrego's arrest was even subject to allegations of corruption. It is believed the Mexican government knew all García Ábrego's whereabouts all along and had refused to arrest him due to information he possessed about the extent of corruption within the government. The arresting officer, a FJP commander, is believed to have received a bullet-proof Mercury Grand Marquis and US$500,000 from a rival cartel for enacting the arrest of García Ábrego.[32]

Further theories put forward to allege the arrest of García Ábrego was to satisfy U.S. demands and meet certification, from the Department of Justice (DOJ), as a trade partner, the vote set to take place on 1 March. García Ábrego was apprehended on 14 January 1996, and Mexico shortly after received certification on 1 March.[33]

- United States v. García Ábrego

Upon his capture outside the city of Monterrey, Nuevo León, the drug lord was flown to Mexico City where U.S. federal agent took him on a private plane to Houston, Texas.[34] Wearing slacks and a striped shirt, García Ábrego was immediately extradited to the United States where he was interviewed by an FBI agent, and confessed to have "ordered people murdered and tortured", bribed top Mexican officials, and smuggled tons of narcotics into the United States.[35] His prosecutors, however, tried García Ábrego as a U.S. citizen because he also had an American birth certificate, although Mexican authorities claimed the certificate was "fraudulent."[36] He also had an official birth certificate that claimed García Ábrego was indeed born in Mexico.[37] According to The Brownsville Herald, García Ábrego went into the courtroom grinning and talking animatedly with his lawyers who helped him translate his words from Spanish into the English language.[38] Hours after the judge told García Ábrego that he was going to spend the rest of his life in prison, the death penalty was out of the question for the prosecutors.[39]

According to the factual documents presented in court on 8 May 1998, the Matamoros-based criminal syndicate of the Gulf Cartel was responsible for trafficking tremendous amounts of narcotics into the United States from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s, and García Ábrego was given eleven life sentences in prison.[40] During the four-week trial, 84 witnesses, ranging from "law enforcement officers to convicted drug smugglers", confessed that García Ábrego smuggled loads of Colombian cocaine on planes and then stored them in several border cities along the Mexico–United States border before being smuggled to the Rio Grande Valley.[41]

In addition, it was brought up that García Ábrego had previously been arrested in Brownsville, Texas for six-year-old auto theft charges, but was released later with no charges whatsoever.[42] Two men from the Rio Grande Valley were charged before the drug lord's arrest for laundering more than $30 million for García Ábrego.[43] He was also held responsible in 1984 for the massacre of 6 people in La Clínica Raya, a hospital where rival drug members were being treated, and was also blamed for the massacre of the Cereso prison in 1991, where 18 prisoners were slain—both in Matamoros, Tamaulipas.[44][45][46]

After García-Ábrego era

Following Ábrego's 1996 arrest by Mexican authorities and subsequent deportation to the United States, a power vacuum was left and several top members fought for leadership.[47]

Humberto García Ábrego, brother of Juan García Ábrego, tried to take the lead of the Gulf Cartel, but ultimately failed in his attempt.[48] He did not have the leadership skills nor the support of the Colombian drug-provisioners. In addition, he was under observation and was widely known, since his surname meant more of the same.[49] He was to be replaced by Óscar Malherbe de León and Raúl Valladares del Ángel, until their arrest a short time later,[50] causing several cartel lieutenants to fight for the leadership. Malherbe tried to bribe officials $2 million for his release, but it was denied.[51] Hugo Baldomero Medina Garza, known as El Señor Padrino de los Tráilers (the lord of the Trailers), is considered one of the most important members in the rearticulation of the Gulf Cartel.[52] He was one of the top officials of the cartel for more than 40 years, trafficking about 20 tons of cocaine to the United States each month.[53] His luck ended in November 2000 when he was captured in Tampico, Tamaulipas and imprisoned in La Palma.[54] After Medina Garza's arrest, his cousin Adalberto Garza Dragustinovis was investigated for allegedly forming part of the Gulf Cartel and for money-laundering, but the case is still open.[55] The next in line was Sergio Gómez alias El Checo, however, his leadership was short-lived when he was assassinated in April 1996 in Valle Hermoso, Tamaulipas.[56] After this, Osiel Cárdenas Guillén took control of the cartel in July 1999 after assassinating Salvador Gómez Herrera alias El Chava, co-leader of the Gulf Cartel and close friend of him, earning his name as the Mata Amigos (Friend Killer).[57]

Osiel Cárdenas Guillén's era

As confrontations with rival groups heated up, Osiel Cárdenas Guillén sought and recruited over 30 deserters of the Mexican Army's elite Grupo Aeromóvil de Fuerzas Especiales (GAFE) to form part of the cartel's armed wing.[58] Los Zetas, as they are known, served as the hired private mercenary army of the Gulf Cartel. Nevertheless, after the arrest and extradition of Cárdenas, internal struggles led to a rupture between the Gulf and the Zetas.[59]

Los Zetas

In 1997 the Gulf Cartel began to recruit military personnel whom Jesús Gutiérrez Rebollo, an Army General of that time, had assigned as representatives from the PGR offices in certain states across Mexico. After his imprisonment a short time later, Jorge Madrazo Cuéllar created the National Public Security System (SNSP), to fight the drug cartels along the U.S.–Mexico border. After Osiel Cárdenas Guillén took full control of the Gulf Cartel in 1999, he found himself in a no-holds-barred fight to keep his notorious organization and leadership untouched, and sought out members of the Mexican Army Special Forces to become the military armed-wing of the Gulf Cartel.[60] His goal was to protect himself from rival drug cartels and from the Mexican military, to perform vital functions as the leader of the most powerful drug cartel in Mexico.[61] Among his first contacts was Arturo Guzmán Decena, an Army lieutenant who was reportedly asked by Cárdenas to look for the "best men possible."[62] Consequently, Guzmán Decenas deserted from the Armed Forces and brought more than 30 army deserters to form part of Cárdenas' new criminal paramilitary wing.[63] They were enticed with salaries much higher than those of the Mexican Army.[64] Among the original defectors were Jaime González Durán,[65] Jesús Enrique Rejón Aguilar,[66] Miguel Treviño Morales,[67] and Heriberto Lazcano,[68] who would later become the supreme leader of the independent cartel of Los Zetas. The creation of Los Zetas brought a new era of drug trafficking in Mexico, and little did Cárdenas know that he was creating the most violent drug cartel in the country.[69] Between 2001 and 2008, the organization of the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas was collectively known as La Compañía (The Company).[70]

One of the first missions of Los Zetas was to eradicate Los Chachos, a group of drug traffickers under the orders of the Milenio Cartel, who disputed the drug corridors of Tamaulipas with the Gulf Cartel in 2003.[71] This gang was controlled by Dionisio Román García Sánchez alias El Chacho, who had decided to betray the Gulf Cartel and switch his alliance with the Tijuana Cartel; however, he was eventually killed by Los Zetas.[72] Once Cárdenas consolidated his position and supremacy, he expanded the responsibilities of Los Zetas, and as years passed, they became much more important for the Gulf Cartel. They began to organize kidnappings;[73] impose taxes, collect debts, and operate protection rackets;[74] control the extortion business;[75] securing cocaine supply and trafficking routes known as plazas (zones) and executing its foes, often with grotesque savagery.[62] In response to the rising power of the Gulf Cartel, the rival Sinaloa Cartel[76] established a heavily armed, well-trained enforcer group known as Los Negros.[77] The group operated similar to Los Zetas, but with less complexity and success. There is a circle of experts who believe that the start of the Mexican Drug War did not begin in 2006 (when Felipe Calderón sent troops to Michoacán to stop the increasing violence), but in 2004 in the border city of Nuevo Laredo, when the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas fought off the Sinaloa Cartel and Los Negros.[78]

In 2002, there were three main divisions of the Cartel, all ruled over by Cárdenas and led by: Jorge Eduardo "El Coss" Costilla Sanchez, Antonio "Tony Tormenta" Cárdenas Guillen, and Heriberto "El Lazca" Lazcano Lazcano.[79]

Upon the arrest of the Gulf Cartel boss Cárdenas in 2003 and his extradition in 2007, the panorama for Los Zetas changed—they started to become synonymous with the Gulf Cartel, and their influences grew within the organization.[80] Los Zetas began to grow independently from the Gulf Cartel, and eventually a rupture occurred between them in early 2010.[81][82]

Standoff with U.S. agents

On 9 November 1999, two U.S. agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and FBI were threatened at gunpoint by Cárdenas Guillén and approximately fifteen of his henchmen in Matamoros. The two agents traveled to Matamoros with an informant to gather intelligence on the operations of the Gulf Cartel.[83][84] Cárdenas Guillén demanded the agents and the informant to get out of their vehicle, but they refused to obey his orders. The incident escalated as Cárdenas Guillén threatened to kill them if they did not comply and as his gunmen prepared to shoot. The agents tried to reason with him that killing U.S. federal agents would bring a massive manhunt from the U.S. government. Cárdenas Guillén eventually let them go and threatened to kill them if they ever returned to his home turf.[83]

The standoff triggered a massive law enforcement effort to crackdown on the leadership structure of the Gulf Cartel. Both the Mexican and U.S. government increased their efforts to apprehend Cárdenas Guillén. Before the standoff, he was regarded as a minor player in the international drug trade, but this incident catapulted his reputation and made him one of the most-wanted criminals.[85] The FBI and the DEA mounted numerous charges against him and issued a US$2 million bounty for his arrest.[86]

Arrest and extradition

The former leader of the Gulf Cartel, Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, was captured in the city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, on 14 March 2003, in a shootout between the Mexican military and Gulf Cartel gunmen.[87] He was one of the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives, which was offering $2 million for his capture.[88] According to government archives, this six-month military operation was planned and carried out in secret; the only people informed were the President Vicente Fox, the Secretary of Defense in Mexico, Ricardo Clemente Vega García, and Mexico's Attorney General, Rafael Macedo de la Concha.[89] After his capture, Cárdenas was sent to the federal, high-security prison La Palma.[90] However, it was believed that Cárdenas still controlled the Gulf Cartel from prison,[91] and was later extradited to the United States, where he was sentenced to 25 years in a prison in Houston, Texas for money laundering, drug trafficking and death threats to U.S. federal agents.[92][93] Reports from the PGR and El Universal state that while in prison, Cárdenas and Benjamín Arellano Félix, from the Tijuana Cartel, formed an alliance. Moreover, through handwritten notes, Cárdenas gave orders on the movement of drugs along Mexico and to the United States, approved executions, and signed forms to allow the purchase of police forces.[94] And while his brother Antonio Cárdenas Guillén led the Gulf Cartel, Cárdenas still made vital orders from La Palma through messages from his lawyers and guards.[94]

The arrest and extradition of Cárdenas, however, caused for several top lieutenants from both the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas to fight over important drug corridors to the United States, especially the cities of Matamoros, Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa, and Tampico—all situated in the state of Tamaulipas. They also fought for coastal cities Acapulco, Guerrero and Cancún, Quintana Roo; the state capital of Monterrey, Nuevo León, and the states of Veracruz and San Luis Potosí.[95] Through his violence and intimidation, Heriberto Lazcano took control of both Los Zetas and the Gulf Cartel after Cardenas' extradition.[96] Lieutenants that were once loyal to Cárdenas began following the commands of Lazcano, who tried to reorganize the cartel by appointing several lieutenants to control specific territories.Morales Treviño was appointed to look over Nuevo León;[97] Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez in Matamoros;[98] Héctor Manuel Sauceda Gamboa, nicknamed El Karis, took control of Nuevo Laredo;[99] Gregorio Sauceda Gamboa, known as El Goyo, along with his brother Arturo, took control of the Reynosa plaza;[100] Arturo Basurto Peña, alias El Grande, and Iván Velázquez-Caballero alias El Talibán took control of Quintana Roo and Guerrero;[101] Alberto Sánchez Hinojosa, alias Comandante Castillo, took over Tabasco.[102] However, continual disagreement was leading the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas into an inevitable rupture. On 18 August 2013, Gulf Cartel leader Mario Ramirez Trevino was captured.[103]

- United States vs Osiel Cárdenas Guillén

In 2007, Cárdenas was extradited to the United States and charged with the involvement of conspiracies to traffic large amounts of marijuana and cocaine, violating the "continuing-criminal-enterprise statute" (also known as the "drug kingpin statute"), and for threatening two U.S. federal officers.[104] The standoff the two agents had with the drug lord in 1999 in the city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas led for the U.S. to indict Cárdenas and pressure the Mexican government to capture him.[105] In 2010 he was finally sentenced to 25 years in prison after being charged with 22 federal charges;[106] the courtroom was locked and the public prevented from witnessing the proceeding.[107] The proceedings took place in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas in the border city of Brownsville, Texas.[108] Cárdenas has been isolated from interacting with other prisoners in the supermax prison he is in.[109]

Nearly $30 million of the former drug lord's assets were distributed among several Texan law enforcement agencies.[110] In exchange for another life-sentence, Cárdenas agreed to collaborate with U.S. agents in intelligence information.[111] The U.S. federal court awarded two helicopters owned by Cárdenas to the Business Development Bank of Canada and the GE Canada Equipment Financing respectively. Both of them were bought from "drug proceeds".[112]

Rupture from Los Zetas

It is unclear which of the two – the Gulf Cartel or Los Zetas – started the conflict that led to their break up. It is clear, however, that after the capture and extradition of Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, Los Zetas outclassed the Gulf Cartel in revenue, membership, and influence.[113] Some sources reveal that as a result of the supremacy of Los Zetas, the Gulf Cartel felt threatened by the growing force of their enforcer group and decided to curtail their influence, but eventually failed in their attempt, instigating a war.[114] According to narco-banners left by the Gulf Cartel in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, and Reynosa, Tamaulipas, the reason for their rupture was that Los Zetas had expanded their operations to include extortion, kidnapping, assassinations, theft, and other actions with which it disagreed.[115] Unwilling to stand for such abuse, Los Zetas responded and countered the accusations by posting their own banners throughout Tamaulipas. They pointedly noted that they had carried out executions and kidnappings under orders of the Gulf Cartel when they served as their enforcers, and they were created by them for that sole purpose.[116] Also, Los Zetas mentioned that the Gulf Cartel also kills innocent civilians, and then blames them for their atrocities.[116]

Nevertheless, other sources also reveal that Antonio Cárdenas Guillén, brother of Osiel and one of the successors of the Gulf Cartel, was addicted to gambling, sex, and drugs, leading Los Zetas to consider his leadership as a threat to the organization.[117] Other reports mention, however, that the rupture occurred due to a disagreement about who would take on the leadership of the cartel after the extradition of Osiel. The candidates of the Gulf Cartel were Antonio Cárdenas and Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez, while Los Zetas wanted the leadership of their current head, Heriberto Lazcano Lazcano.[118] Other sources, however, mention that the Gulf Cartel began looking to form a truce with their Sinaloa Cartel rivals, and Los Zetas did not want to recognize the treaty settlement, which led them to act independently and eventually break apart.[119] On the other hand, other sources reveal that Los Zetas separated from the Gulf Cartel to ally with Beltrán-Leyva Cartel, which led to conflict between them.[120] Other sources mention that what initiated the conflict between them was when Samuel Flores Borrego, alias El Metro 3, lieutenant of the Gulf Cartel, killed Sergio Peña Mendoza, alias El Concorde 3, lieutenant of Los Zetas, due to a disagreement for the drug corridor of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, whom both protected.[121] Soon after his death, Los Zetas demanded the Gulf Cartel to hand over the killer, but they didn't, and observers believe that triggered the war.[122]

Tamaulipas was mostly spared from the violence until early 2010, when the Gulf Cartel's enforcers, Los Zetas, split from and turned against the Gulf Cartel, sparking a bloody turf war. When the hostilities began, the Gulf organization joined forces with its former rivals, the Sinaloa Cartel and La Familia Michoacana, aiming to take out Los Zetas.[123][124] Consequently, Los Zetas allied with the Juárez Cartel, the Beltrán-Leyva Cartel and the Tijuana Cartel.[125][126]

Antonio Cárdenas Guillén's era

Osiel Cárdenas' brother, Antonio Cárdenas Guillén, along with Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez (El Coss), a former policeman, filled in the vacuum left by Osiel and became the leaders of the Gulf Cartel.[127] The death of Antonio allowed for Costilla Sánchez to become the co-leader of the Gulf Cartel and head of the Metros, one of the two factions within the Gulf Cartel.[128][129] Mario Cárdenas Guillén, brother of Osiel and Antonio, is the other leader of Gulf Cartel and head of the Rojos, the other faction within the Gulf Cartel and the parallel version of the Metros.[130][131]

Costilla was often viewed as the "strongest leader" of the two, but collaborated with Antonio Cárdenas, who acted as representative of his jailed brother.[132] However, Antonio died in an eight-hour shooting with the Mexican government forces on 5 November 2010, in the border city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas.[133] Government sources claimed that this operation—where more than 660 marines, 17 vehicles, and 3 helicopters participated—left 8 dead: three marines, one soldier, and four gunmen, including Antonio Cárdenas.[134] Other sources mention that one news reporter was also killed in the crossfire.[135] This military-led operation was a result of more than six months of intelligence work.[136] Milenio Television mentioned that the Mexican authorities had tried to apprehend Cárdenas Guillén twice before this incident, but that his personal gunmen had distracted the Mexican forces and allowed him to be escorted in his armored vehicle.[137]

The confrontations started around 10:00 am, and extended to 06:00 pm, around the time Cárdenas Guilén was killed. The intense shootings provoked the temporary closure of three international bridges in Matamoros,[138] along with the University of Texas at Brownsville, just across the border.[139] Public transportation and school classes in Matamoros were canceled, along with the suspension of activities throughout the municipality, since the cartel members hijacked the units of public transport and made dozens of roadblocks to prevent the mobilization of the soldiers, marines, and federal police forces.[140] The street confrontations generated a wave of panic among the population and caused the publication and broadcast of messages through social networks like Twitter and Facebook, reporting the clashes between authorities and the cartel members.[141] When the Mexican authorities reached the spot where Antonio Cárdenas (Tony Tormenta) was present, the gunmen received the soldiers and cops with grenades and high-calibre shots. Reports mention that Antonio Cárdenas was being protected by the Los Escorpiones (The Scorpions), the alleged armed wing of the Gulf Cartel and the personal army of Antonio Cárdenas, who was serving as snipers and bodyguards for him.[142] La Jornada newspaper mentioned that over 80 SUV's packed with gunmen fought to protect Cárdenas Guillén, and over 300 grenades were used in the shootout that day.[143] And even after the drug lord was killed, the roadblocks continued throughout the rest of the day.[144]

The Guardian newspaper mentioned that in a YouTube video, a convoy of SUV's filled with gunmen and pickups packed with marines were seen in a chase through the streets of Matamoros, Tamaulipas. And although there wasn't any visible confrontation between the two, the intensity of the situation was clear through the background noises of grenade explosions and automatic gunfire.[145] A news video from Televisa, also on YouTube, shows images from the confrontations of that day.[146] Moreover, several bystanders also recorded the shootouts.[147][148][149]

Nevertheless, according to the newspapers The Brownsville Herald and The Monitor from across the border in Brownsville, Texas and McAllen, Texas, around 50 people were killed in the gunfights.[150][151][152][153][154] Although not confirmed, KVEO-TV, several online sources and witnesses, along with one law enforcement officer who preferred to keep his name anonymous, mentioned that more than 100 people died that day in Matamoros.[155][156][157][158][159][160][161] The death of Antonio Cárdenas Guillen also caused a spiral of violence in Reynosa, Tamaulipas a number of days after he was killed.[162] Moreover, his death also generated a turf war with Los Zetas in the city of Ciudad Mier, Tamaulipas, resulting in the exodus of more than 95% of its population.[163] Banners written by Los Zetas, the Gulf Cartel's former armed wing, appeared all across Mexico, celebrating the death of Cárdenas Guillén.[164][165] United States President, Barack Obama, called the President of Mexico, Felipe Calderón, congratulating him and the Mexican forces for the operation in Matamoros, and reiterated his effort against organized crime.[166]

After this incident, there was a huge division of opinions over the fate of the Gulf Cartel. Some experts believed that the death of Antonio Cárdenas would be dreadful for the Gulf Cartel, and that Los Zetas would overthrow them and eventually take control of Tamaulipas.[167] Others explained how his death allowed Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez to take full directive of the cartel, and that would tighten relations with Colombia and straighten the Gulf Cartel's path, something quite difficult with Antonio Cárdenas as co-leader.[168]

Los Escorpiones

Los Escorpiones, also called Grupo Escorpios,[169] (The Scorpions), was believed to be the mercenary group that protected Antonio Cárdenas Guillén, the former leader of the organization.[170] According to reports by the Mexican government, Los Escorpiones was created by Antonio Cárdenas Guillen and is composed of over 60 civilians, former police officers, and ex-military officials. According to El Universal, there are several music videos on YouTube that exalt the power of this armed group through narcocorridos.[171] After the rupture between the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas (which until then had served as the cartel's armed wing), Los Escorpiones became the armed wing of the entire Gulf organization.[172] The first mention of Los Escorpiones on the media was in 2008, when El Universal wrote an article about some "protected witnesses" from the Gulf Cartel who denounced the alliance between the Beltrán-Leyva Cartel and Los Zetas to the Mexican authorities, and that the Gulf Cartel had created Los Escorpiones to stop and balance the growing hegemony of Los Zetas.[173]

However, his brother Osiel Cárdenas Guillén disapproved the existence of this mercenary group, since he had created Los Zetas, the parallel version of Los Escorpiones, and they had turned against the organization.[174] El Universal reported that Mexican authorities identified the gunmen that were engaging in confrontations against the troops in Matamoros, Tamaulipas as members of the Los Escorpiones group. Along with Antonio Cárdenas, the following members of Los Escorpiones were killed: Sergio Antonio Fuentes, alias El Tyson or Escorpión 1; Raúl Marmolejo Gómez, alias Escorpión 18; Hugo Lira, alias Escorpión 26; and Refugio Adalberto Vargas Cortés, alias Escorpión 42.[175] The arrests of Marco Antonio Cortez Rodríguez alias Escorpión 37 and of Josué González Rodríguez alias Escorpión 43—the two who were hospitalized after the shootout of 5 November 2010—allowed for the Mexican forces to understand the structure of Los Escorpiones.[176]

Present-day

Metros and Rojos infighting

.jpg.webp)

In the late 1990s, Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, the former leader of the Gulf cartel, had other similar groups besides Los Zetas established in several cities in Tamaulipas.[177] Each of these groups were identified by their radio codes: the Rojos (The Red ones) were based in Reynosa; the Metros were headquartered in Matamoros; and the Lobos (The wolves) were established in Laredo.[177] The infighting between the Metros and the Rojos of the Gulf cartel began in 2010, when Juan Mejía González, nicknamed El R-1, was overlooked as the candidate of the regional boss of Reynosa and was sent to the "Frontera Chica", an area that encompasses Miguel Alemán, Camargo and Ciudad Mier – directly across the U.S.–Mexico border from Starr County, Texas. The area that Mejía González wanted was given to Samuel Flores Borrego, suggesting that the Metros were above the Rojos.[177]

Unconfirmed information released by The Monitor indicated that two leaders of the Rojos, Mejía González and Rafael Cárdenas Vela, teamed up to kill Flores Borrego.[177] Cárdenas Vela had held a grudge on Flores Borrego and the Metros because he believed that they had led the Mexican military to track down and kill his uncle Antonio Cárdenas Guillén on 5 November 2010.[177][178] Other sources indicate that the infighting could have been caused by the suspicions that the Rojos were "too soft" on the Gulf cartel's bitter enemy, Los Zetas.[179] When the Gulf cartel and Los Zetas split in early 2010, some members of the Rojos stayed with the Gulf cartel, while others decided to leave and join the forces of Los Zetas.[180]

InSight Crime explains that the fundamental disagreement between the Rojos and the Metros was over leadership. Those who were more loyal to the Cárdenas family stayed with the Rojos, while those loyal to Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez, like Flores Borrego, defended the Metros.[179]

Originally, the Gulf cartel was running smoothly, but the infighting between the two factions in the Gulf cartel triggered when Flores Borrego was killed on 2 September 2011.[177] When the Rojos turned on the Metros, the largest faction in the Gulf cartel, firefights broke throughout Tamaulipas and drug loads were stolen among each other, but the Metros managed to retain control of the major cities that stretched from Matamoros to Miguel Alemán, Tamaulipas.[181]

Some experts have found it difficult to argue that the Gulf Cartel does not impose a direct threat to the state since they "do not seek political change", and that they only want to be left alone with their business. Observations indicate that the Gulf Cartel controls territories and imposes its own rules—often violent and bloody—over the population. And in doing so, they inherently become a "competitor" with the state, who also claims sovereignty over its territories.[182] Like other drug trafficking organizations, the Gulf Cartel also subverts government institutions, particularly at state and local levels, by using their large profits to bribe officials.[183]

Presence in the U.S.

The Gulf Cartel has important cells operating inside the United States—in Mission, Roma, and Rio Grande City—for example, and their presence is expanding.[184] Thomas A. Shannon, a U.S. diplomat and ambassador, stated that criminal organizations like the Gulf Cartel have "substantially weakened" the institutions in Mexico and Central America, and have generated a surge of violence in the United States.[185] The U.S. National Drug Threat Assessment mentioned that the drug trafficking organizations like the Gulf Cartel tend to be less structured in U.S. than in Mexico, and often rely on street gangs to operate inside the United States.[186] The arrest of several Gulf Cartel lieutenants, along with the drug-related violence and kidnappings, have raised concerns among Texas officials that the drug war in Mexico and the drug cartels are taking hold in Texas.[187] The strong ties the Gulf Cartel has with the prison gangs in the United States have also raised concern to American officials.[188] Reports mention that Mexican drug cartels operate in more than 1,000 cities in the United States.[189] In 2013, high ranking Gulf Cartel member Aurelio Cano Flores became the highest cartel member to be convicted by a U.S. jury in 15 years[190] In January 2020, high-ranking U.S. Gulf Cartel member Jorge Costilla-Sanchez pleaded guilty to an international drug trafficking conspiracy to distribute cocaine and marijuana into the United States.[191]

Presence in Europe

The Gulf Cartel is believed to have ties with the 'Ndrangheta, an organized crime group in Italy that also has ties with Los Zetas.[192] Reports indicated that the Gulf Cartel was using the BlackBerry smartphones to communicate with 'Ndrangheta, since the texts are "normally difficult to intercept".[193] In 2009, the Gulf organization concluded that expanding their market opportunities in Europe, combined with the euro strength against the U.S. dollar, justified establishing an extensive network in that continent. The main areas of demand and drug consumption are in Eastern Europe, the successor states of the Soviet Union. In Western Europe, the primarily increase has been in the use of cocaine.[194] Along with the market in the United States, the drug market in Europe is among the most lucrative in the world, where the Mexican drug cartels are believed to have deals with the mafia groups of Europe.[195]

Presence in Africa

The Gulf Cartel and other Mexican drug trafficking groups are active in the northern and western parts of Africa.[196] Although cocaine is not grown in Africa, Mexican organizations, such as the Gulf Cartel, are currently exploiting West Africa's struggling rule-of-law caused by war, crime and poverty, to stage and expand supply routes to the increasingly lucrative European illegal drug market.[197][198]

Gulf Cartel vs. Los Zetas

The rumors of the broken alliance between the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas began on blogs and mass emails in September 2009, but it remained pretty much the same throughout that year—a rumor. But on 24 February 2010, hundreds of trucks marked with C.D.G, XXX, and M3 (the insignias of the Gulf Cartel) began to hit the streets of northern Tamaulipas.[199] The clash between these two groups first happened in Reynosa, Tamaulipas and then expanded to Nuevo Laredo and Matamoros.[200] The war then spread out through 11 municipalities of Tamaulipas, 9 of them bordering the state of Texas.[201] Soon, the violence generated between these two groups had spread to Tamaulipas' neighboring states of Nuevo León and Veracruz.[202][203] Their conflict has even occurred on U.S. soil, where the Gulf Cartel killed two Zeta members in Brownsville, Texas on 5 October 2010.[204] In the midsts of violence and panic, local authorities and the media tried to minimize the situation and claim that "nothing was occurring", but the facts were impossible to cover up.[205] Confrontations between these two groups have paralyzed entire cities in broad daylight.[206] Several witnesses claimed that many of the municipalities throughout Tamaulipas were "war zones", and that many businesses and houses were burned down, leaving areas in "total destruction".[207] The bloodbath in Tamaulipas has caused thousands of deaths, but most of shootings and body counts often go unreported.[208] The complexity and territorial advantage of Los Zetas forced the Gulf Cartel to seek for an alliance with the Sinaloa Cartel and La Familia Michoacana; in addition, Stratfor mentioned that these three organizations also united because they hold a "profound hate" for Los Zetas.[209] Consequently, Los Zetas joined forces with the Beltrán Leyva Cartel and the Tijuana Cartel to counterattack the opposing cartels.[210]

On 10 November 2014, a document from the Mexican government was released to the media and claimed that Los Rojos faction of the Gulf Cartel was planning to ally with Los Zetas. The potential alliance was conducted by Juan Reyes Mejía González (alias "R1"), from the Gulf Cartel; and Rogelio González Pizaña (alias "Z-2"), from Los Zetas. The latter was released from prison months earlier even though he was scheduled to serve 16-years behind bars in January. Authorities believe that González Pizaña reincorporated in organized crime and decided to join with the Gulf Cartel to end the war with Los Zetas, and bring back the "old school" ways when they were together.[211]

Fragmentation

In June 2020, Insight Crime journalist Victoria Dittmar claimed that the Gulf Cartel had undergone "fragmentation" at some point in time.[212] Los Pelones emerged as an independent cartel during this fragmentation as well.[212] However, remnants still exist in Tamaulipas.[212]

Tamaulipas: State corruption

Political corruption

The drug violence and political corruption that has plagued Tamaulipas, the home state of the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas, has fueled thoughts of Tamaulipas becoming a "failed state" and a haven for drug traffickers and criminals of all kinds.[213] The massacre of the 72 migrants and the clandestine mass graves with more than 250 bodies in San Fernando, Tamaulipas,[214][215] mounted with the assassination of the governor candidate Rodolfo Torre Cantú (2010),[216] the increasing violence generated between drug groups, and the state's inability to ensure tranquility, has led specialists to conclude that "neither the regional nor federal government have control over the territory of Tamaulipas."[217]

Although drug-related violence has existed since the early beginnings of the Gulf Cartel, it often happened in low-profile levels, while the government agreed to "look the other way" while the drug traffickers went about their business—as long as they behaved.[218] Back in the days of the 71-year rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), it was believed that they ran exactly that show: if the drug cartels got off the line, the Mexican government would conduct some arrests, make some disappearances, and the drug lords would get their people straight and back on the line again.[219] After the PRI lost the presidency in 2000 to the National Action Party (PAN), the arrangement between the government and the cartels was lost, as well the pax mafiosa.[220][221] Moreover, the state of Tamaulipas was no exception; according to Santiago Creel, a PAN politician and pre-candidate for the 2012 presidency, the PRI in Tamaulipas has protected the Gulf Cartel for years.[222][223] In addition, El Universal newspaper mentions that the narco-corruption in Tamaulipas is due to the fact the opposing political parties, the PAN and the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), rarely win an election and "practically do not exist".[224] PRI's main opposition party, the PAN, claimed that government elections in Tamaulipas are likely to encounter an "organized crime influence."[225]

The Excélsior newspaper reported that the former governors of Tamaulipas, Manuel Cavazos Lerma (1993–1999), Tomás Yarrington (1999–2004), and Eugenio Hernández Flores (2005–2010) have had close ties with the Gulf Cartel.[226] On 30 January 2012, the Attorney General of Mexico issued a communiqué ordering the past three governors of Tamaulipas and their families to remain in the country as they are being investigated for possible cooperation with the Mexican drug cartels.[227][228] The municipal president of Tampico, Tamaulipas, Óscar Pérez Inguanzo, was arrested 12 November 2011, due to his "improper exercise of public functions and forgery" of certain documents.[229] In addition, La Jornada mentions that the Gulf Cartel owns "all of Matamoros", where they act as the State itself and conduct all forms of criminal activities.[230] In mid-2010, Eugenio Hernández Flores, the governor of Tamaulipas and Óscar Luebbert Gutiérrez, the mayor of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, both members of the PRI, were criticized for claiming that there were no armed confrontations in Tamaulipas and that the violence was "only a rumor."[231] Months later, Hernández Flores finally recognized that several parts of Tamaulipas were "being overrun by organized crime violence."[232] Luebbert Gutiérrez later recognized the work of the federal troops and acknowledged that his city was experiencing "an escalation in violence."[233]

On 5 June 2016, citizens from Tamaulipas elected a governor from the opposition party, Fransico Javier Garcia Cabeza de Vaca member of Accion Nacional (National Action). It is the first time in 87 years, a governor from the opposition wins in the state.[234] He won under the slogan "winds of change are coming" to Tamaulipas.[235] While his election did not have that much substance in a public policy perspective, its rhetoric of a peaceful transition, enabled him to defeat by double digits the candidate from the ruling party, Baltazar Manuel Hinijosa Ochoa.[236]

Both candidates have and continue to face accusations of receiving illicit money from the Gulf Cartel while being mayors of two border towns. In 1986, according to Proceso, Cabeza de Vaca was arrested for stealing weapons under the orders for a Drug Trafficking Organization (DTOs) of the Gulf Cartel.[237] Cabeza de Vaca is accused by a Bloomberg/El Financiero of having a big and unexplained wealth of 951 million pesos.[238] Cabeza de Vaca is accused of not reporting its total wealth and having properties both in Texas, Tamaulipas, and Mexico City. Cabeza de Vaca has been for 11 years a public servant, which questions according to El Financiero, the origin of its wealth. Balatazar Hinojosa Ochoa is also accused of coopting with DTOs of the Gulf Cartel while being mayor of Matamoros in 2006. In goes into the extent, in a recent book called Tamaulipas; La casta de los narcogobernadores: un eastern mexicano is accused of being present while former governor Tomas Yarrington, also accused of involvements with DTOs of the Gulf Cartel, received illicit money from the Gulf Cartel to finance its campaign for governor.[239] Also according to Proceso, Baltazar Hinojosa is under investigation by the United States Department of Treasury for laundering money through the Panama Papers target, the law firm Mossack Fonseca. According to the media outlet, Baltazar Hinojosa brother in law, owns a shell company created by the law firm, where its board of directors' members is his wife and three daughters.[240]

Prison breaks

On 25 March 2010, in the city of Matamoros, 40 inmates escaped from a federal prison.[241] Authorities are still trying to understand how the prisoners escaped.[242] The authorities mentioned that the incident is "under investigation", but did not give further information.[243] In the border city of Reynosa, 85 inmates escaped from a prison on 10 September 2010.[244] Reports first indicated that there were 71 fugitives, but the correct figures were later released.[245] On 5 April 2010, in the same prison, a convoy of 10 trucks filled with gunmen broke into the cells and liberated 13 inmates, and the authorities later mentioned that 11 of them were "extremely dangerous."[246] In Nuevo Laredo on 17 December 2010, about 141 inmates escaped from a federal prison. At first, estimates mentioned that 148 inmates had escaped, but later counts gave the exact figures.[247] The federal government "strongly condemned" the prison breaks and said that the work by the state and municipal authorities of Tamaulipas "lack effective control measures" and urged them to strengthen their institutions.[248] A confrontation inside a maximum security prison in Nuevo Laredo on 15 July 2011, left 7 inmates dead and 59 escaped.[249] The 5 guards that were supposed to supervise have not been found, and the Federal government urged the state and municipal authorities to strengthen the security of their prisons.[250] Consequently, the federal government did not hesitate to assign the Mexican Army and the Federal Police to vigilate the prisons until further notice; they were also left in charge of searching for the fugitives.[251] CNN mentioned that the state government of Tamaulipas later recognized "their inability to work with the federal government."[252] In a prison in the state of Zacatecas, on 16 May 2009, an armed commando liberated 53 Gulf Cartel members using 10 trucks and even a helicopter.[253]

According to CNN, more than 400 prison inmates escaped from several prisons in Tamaulipas from January 2010 to March 2011 due to corruption.[254]

Police corruption

The Excélsior newspaper mentioned that the police forces in the state of Tamaulipas are the "worst paid in Mexico" despite being "one of the states hardest hit by violence."[255] They also reported that in Aguascalientes, a state where violence levels are much lower, policemen are paid five times more than in Tamaulipas. In fact, they are paid around $3,618 pesos (about US$260) a month in all of Tamaulipas.[256] As a result, most of the police forces in Tamaulipas are believed to be "corrupt" due to their low wages and the presence of organized crime, who can easily bribe them.[257]

On 9 May 2011, the Mexican government, along with Sedena, disarmed all police forces in the state of Tamaulipas, beginning with the cities of Matamoros and Reynosa.[258] In June 2011, the state government of Tamaulipas requested the federal government to send in troops to combat the drug cartels in the area, to "consolidate actions on public safety" and "strengthen the capacity of their institutions."[259] The Joint Operation Nuevo León-Tamaulipas issued in 2007, along with several other military-led operation by the federal government, have brought thousands of troops to restore order in Tamaulipas.[260] CNN mentioned that the troops "replaced half of the policemen" in the state of Tamaulipas.[261] On 7 November 2011, about 1,660 policemen were released from their duties because they had either failed their control tests or refused to take them.[262]

Although there have been efforts by the federal government to wipe out police corruption, Terra Networks published an article of a witness who said that the police forces in Matamoros work as "informants for the Gulf Cartel" and report on the activity of the Mexican military, and even "wave at [the cartel members]" when they see them in the streets.[263] El Universal released an article which said that the National Public Security System (SNSP) has condemned the cops' salaries, and demanded the state and municipal authorities to create better paying programs for the policemen so they can have a "just wage" for themselves and their families.[264] The federal government is also constructing three military bases in Tamaulipas: in Ciudad Mier, San Fernando and Ciudad Mante.[265]

Alliances

In 2003, the arrest of several high-profile cartel leaders, including the heads of the Tijuana Cartel and Gulf Cartel, Benjamín Arellano Félix and Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, turned the war on drugs into a trilateral war. While in prison, Cárdenas and Arellano formed an alliance to defend themselves from the Sinaloa and Juarez Cartels,[266] who had also allied with each other, and were planning to take over the smuggling routes and territories of the Gulf and Tijuana Cartel.[267] After a dispute, however, Cárdenas ordered Arellano beaten, and the Gulf-Tijuana alliance ceased to exist at that point. It was reported that after the fallout, Cárdenas ordered Los Zetas to Baja California to wipe out the Tijuana Cartel.[268]

The Sinaloa-Juarez alliance ceased to exist as well due to an unpaid debt in 2007, and now the Sinaloa and Juarez Cartel are at war against each other.[269] Since February 2010, the major cartels have aligned in two factions, one integrated by the Juárez Cartel, Tijuana Cartel, Los Zetas and the Beltrán-Leyva Cartel;[270] the other faction integrated by the Gulf Cartel, Sinaloa Cartel, La Familia Cartel (now extinct) and the Knights Templar Cartel.[271][272]

Structure

The rupture from Los Zetas left Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez and Antonio Cárdenas Guillén in full control of the Gulf Cartel. However, Ezekiel died in a shooting with the Mexican Marines in Matamoros, Tamaulipas in 2010,[273] and Costilla Sanchez became the sole head of the cartel until his arrest in September 2012.[274] Mario Cárdenas Guillén, brother of both Osiel and Antonio, became one of the top lieutenants in the organization after his release from prison in 2007.[275] In addition, within the Gulf Cartel there is believed to be two groups—the Rojos and the Metros.[276] The modus operandi ("mode of operation") of the Gulf Cartel changes whenever the United States attempts to strengthen their domestic policy in reinforcing the borders. When drug trafficking tightens, they usually invest in more sophisticated methods to smuggle drugs, recruit new members, corrupt more officials, seek new ways to remove obstacles that impede the immediate success of the organization, along with many others.[277] Below is the basic structure of the cartel:

- Falcons (Halcones): Considered the "eyes and ears" of the streets, the falcons are the lowest rank position in any drug cartel. They are responsible for supervising and reporting on the activities of the Mexican military and of their rival groups.[278]

- Hitmen (Sicarios): They are the armed group within the drug cartel; they are responsible for carrying out assassinations, kidnappings, thefts, extortions, operating protection rackets, and defending their plaza from the rival groups and the military.[279][280]

- Lieutenants (Lugartenientes): The second-highest position in the drug cartel organization; they are responsible for supervising the sicarios and halcones within their territory. They are allowed to carry low-profile executions without permission from their bosses.[281]

- Drug lords (Capos): This is the highest position in any drug cartel; they are responsible supervising the entire drug industry, appointing territorial leaders, making alliances, and planning high-profile executions.[282]

It's worth noting that there are other operating groups within the drug cartels. For example, the drug producers and suppliers,[283] although not considered in the basic structure, are critical operators of any drug cartel, along with the financers and money launderers.[284][285][286] In addition, the arms suppliers operate in a completely different circle,[287] and are technically not considered part of the cartel's logistics.

In June 2019, Carlos Abraham Ríos Suárez, also known as El Oaxaco, was arrested. He served as head of cartel's operations in Oaxaca.[288]

Modus operandi

Protection racketeering Organized crime groups opt for protection racketeering in an effort to control markets and "maintaining internal order."[289] It is generally seen as a way where criminals change the legal face of security and provide their own form of "insurance".[290] This practice of extorting money from people is also seen in the human trafficking business in Mexico; the cartels threaten smugglers to pay a fee for using the corridors, and if they refuse to pay, drug traffickers respond in a deadly form.[291] The Gulf Cartel operates in a similar way, and often extorts businesses for protection money in the areas where it operates, pledging to kill those who do not agree to pay the fee.[292] In addition, the Mexican drug cartels also tax several Mexican businesses inside the United States and threaten them with property damage and murder if they do not comply.[293]

Kidnappings The Gulf Cartel, along with their rival group Los Zetas, have been the two drug cartels with the most kidnappings in all of Mexico, and "more than half of the country's kidnappings are attributed to them."[294] And, there are several kidnapping rings of the Gulf Cartel throughout several parts of Tamaulipas.[295] The Mexican military mentioned that in the states of Tamaulipas and Nuevo Leon, where the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas fight for territory, abductions are carried out very commonly. An intelligence agency mentioned that the Gulf Cartel kidnaps for three reasons:

- To increase the ranks of their cartel after the deaths or arrests of their members;

- To exterminate members of their rival gangs;

- To kidnap people for money and other ransom.[296]

In April 2011 in the border city of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, 68 kidnapped victims from different parts of Mexico and Central America were found in a safe house of the Gulf Cartel.[297][298] Omar Ortiz, best known for his nickname El Gato, was a former soccer star from C.F. Monterrey who was arrested in January 2012 for working in a kidnapping ring within the Gulf Cartel.[299] The Mexican Lucha libre wrestler Lázaro Gurrola, known as the Estrella Dorada (Golden Star), was also arrested for kidnapping people for the Gulf Cartel.[300]

In the United States, the Gulf Cartel has been responsible for several kidnappings, primarily in the McAllen metropolitan area.[301][302][303] Investigators believe that more unreported kidnappings have occurred in nearby locations.[304] When victims are kidnapped by the drug cartels on American territory, kidnappers usually hide them in the trunk of a car and take them to Mexico.[305] FBI investigators said that victims are "kidnapped, threatened, assaulted, drugged and transported into Mexico to meet with Cartel members."[306] Reports indicated that kidnappers working for the Gulf Cartel train with paintball equipment "to practice simulated kidnapping schemes in order to prepare for the actual kidnapping they intended to commit."[307] In one reported incident, Isaac Sanchez Gutierrez, a man from Palmview, Texas, said he faced an ultimatum: pay $10 million to the Gulf Cartel, or transport 50 drug loads from Mexico into the U.S. in order to free his kidnapped brother.[308]

Human trafficking

Before 2010, it was not clear whether the Gulf Cartel controls the human trafficking business in its territory or whether it simply taxes operators for using their smuggling corridors.[309] La Jornada mentioned that before the rupture with Los Zetas in 2007, the corridor of Reynosa, Tamaulipas was often used for human smuggling.[310] People smuggling is currently controlled by a cell within the Gulf Cartel known as Los Flacos, dedicated to the kidnapping and smuggling of undocumented migrants as far as South America to the United States.[311] It operates primarily on the Tabasco–Veracruz–Tamaulipas corridor.[312] Human trafficking in the Rio Grande Valley has become "ground zero" and was considered the "new Arizona" in December 2011 by the Homeland Security Today.[313]

A U.S. agent mentioned that the drug cartels that operate on the Mexico–United States border, and principally across from Texas, are "in control of not only the narcotrafficking, but also the human smuggling."[314]

Extortion In August 2007, La Maña gang, an alleged sub-group of the criminal group Los Zetas and the Gulf Cartel, was reported to have controlled the extortion business in Matamoros, Tamaulipas.[315] The newspaper La Vanguardia mentioned that the Gulf Cartel receives "large sums of money by extorting businesses" all around Tamaulipas.[316] Many of the extortions are first carried out on the phone.[317] --> Critics say that the strategy of capturing drug kingpins often resulted in the increase in extortion, as the cartels look for other sources of money.[318]

Bribery When the Gulf Cartel was moving tons of cocaine to the United States and moving millions of dollars in cash along the border in the 1970s, Juan García Ábrego decided that he needed more protection. Court documents indicated that García Ábrego was bribing several law enforcement officials, prosecutors, and politicians on both sides on the border to keep himself impune and untouched.[319] His former friends and associates mentioned that the drug lord was paying one of Carlos Salinas de Gortari's deputy attorneys general more than $1.5 million a month for his protection.[320] He is allegedly reported to have been protected by a large private army of gunmen.[321] A retired FBI agent and expert in drug trafficking explained that the Gulf Cartel "relied on bribery" to build its drug empire and consolidate its prominence.[322]

FBI agents have claimed that the Gulf Cartel moves millions of dollars in cash through the Rio Grande Valley each month, a tempting amount for many U.S. officials.[323] Much of the money stays in the area, which has caused several officials—both federal and state—to succumb to the "easy money aspect" the drug money has to offer.[324] The Gulf Cartel also bribes journalists to persuade them not to mention any violent incidents in the media.[325] In addition, due to the low-paying salaries of many policemen, the Gulf Cartel often "buys" many law enforcement officers in Mexico.[326]

Theft Stealing oil from PEMEX and selling it illegally has been one of the many funding activities of the Gulf Cartel.[327] They were reported to have stolen around 40% of the oil products in 2011 in northern Mexico and then selling it illegally in Mexico and in the American black market.[328] One leader of the Gulf Cartel confessed after his apprehension that "drug trafficking is their main business, but due to the difficulties they have been encountering, oil theft has been an important financial cushion" for the cartel.[329] They have also been reported to steal vehicles.[330]

Money laundering Some of the revenue of the Gulf Cartel is often laundered in several bank accounts, properties, vehicles, and gasoline stations.[331] Bars and casinos are often the hubs for money laundering of the drug cartels.[332] Top leaders of the Gulf organization, like Juan García Ábrego, Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez and Antonio Cárdenas Guillén, among others, have been charged by the U.S. government for laundering millions of dollars.[333] Bank accounts inside the United States also launder millions of dollars for the drug lords of the Gulf Cartel.[334] The Economist mentioned in 1997 that the drug money from the Gulf Cartel in the Rio Grande Valley was perhaps moving about $20 billion, and that around 15% of the retailers' gains were from drug money.[335]

Arms trafficking For the most part, the arms trafficking circles of the Gulf Cartel operate directly across the border in the United States, just like most of the criminal groups in Mexico.[336][337][338] Nonetheless, there are indeed circles within the Gulf Cartel that coordinate the arms trafficking routes inside Mexico.[339] Arms trafficking from the U.S. to Mexico, however, is often carried out individually, and there is no criminal group in Mexico or an international organization that is solely dedicated to this activity.[340]

Jesús Enrique Rejón Aguilar, a top-tier Los Zetas boss, was caught on 3 July 2011, and claimed in an interview that was aired on national television that the Gulf Cartel, unlike Los Zetas, has an "easier and quicker access to arms in the United States", and probably works "with some people in the government" to traffic weapons south of the U.S. border.[341]

Prostitution network Prostitution circles are believed to be used by the Gulf Cartel to persuade journalists to favor them in the media.[342] Prostitutes are also used as informants and spies, and provide their sexual favors to extract information from certain targets.[343]

Counterfeiting The Mexican criminal organizations like the Gulf Cartel launder money through counterfeiting, since they are free from taxes and more accessible to people who cannot buy original products.[344] The products sold can be clothing, TVs, video games, music, computer programs, and movies.[345] In 2008 in the state of Michoacán, the Gulf Cartel was reported to have controlled the counterfeit business, where it produced and sold millions of fake CDs and movies.[346]

Police impersonation Reports indicate that gunmen from the Gulf Cartel often impersonate law enforcement officers, using military uniforms to confuse rival drug gangs and move freely through city streets.[347]

Transportation Due to the Gulf Cartel's territory in northern Tamaulipas, primarily in the border cities of Reynosa and Matamoros, they have been able to establish a sophisticated and extensive drug trafficking and distribution network along the U.S.–Mexico border in South Texas.[348] The Mexican drug cartels that operate in the area are currently employing gang members to distribute drugs and conduct other criminal activities on their behalf.[349] Among these gangs, that range from street gangs to prison gangs, are the Texas Syndicate, the Latin Kings, the Mexican Mafia, Puro Tango Blast (Vallucos), the Hermandad de Pistoleros Latinos, and the Tri-City Bombers—all based in the Rio Grande Valley and Webb County, Texas.[350]

While the entire Mexico–United States border has experienced high levels of drug trafficking and other illegal smuggling activities for decades, this activity tends to be concentrated in certain sectors within Texas. Two such sectors are the Rio Grande Valley and West Texas, near the El Paso–Juárez metropolitan area. The high level of legitimate travel and movement of goods and services between border cities in the U.S. and Mexico facilitates the drug business in the area. The majority of the commerce between the United States and Mexico passes through the state of Texas.[351] Due to its multifaceted transportation networks and proximity to major production areas right across the border in Mexico, Texas is a major hub for drug trafficking. According to the National Drug Intelligence Center, drug traffickers commonly use private vehicles and commercial trucks to traffic narcotics throughout the state. The drug organizations usually use the Interstates 10, 20, 25, 30, and 35, as well as U.S. Highways 59, 77, 83, and 281.[352] The Gulf of Mexico also presents a danger to the flow of drugs to Texas; the Port of Houston and the Port of Brownsville enable traffickers to use small vessels and pleasure craft to transport illicit drugs into and from southern Texas.[353]

Illicit drugs also are smuggled into and through Texas via commercial aircraft, cars, buses, passenger trains, pedestrians, and package delivery services. Narcotics are also smuggled through the railroads that connect the U.S. and Mexico. Moreover, the Mexican drug traffickers often use small boats to transport drugs through the coastal areas of South Texas, usually operating at night to prevent them from being spotted by law enforcement officials.[354] Another avenue that they have implemented is to construct tunnels to get their product across the border. By constructing a tunnel, the cartel can get their product across the tight border security with the possibility of no detection.[355] Apart from using these common ways, once the product is across the border, common cars and trucks are used for faster distribution in different cities. To use the seas, the cartel also implemented the use of narco submarines.[356][357][358]

Indictments

On 21 July 2009, the United States DEA announced coordinated actions against the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas drug trafficking organizations. Antonio Cárdenas Guillén, Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez, Heriberto Lazcano Lazcano and 15 of their top lieutenants, have been charged in U.S. federal courts with drug trafficking-related crimes,[359][360] while the U.S. State Department announced rewards totaling US$50 million for information leading to their capture.[359]

In May 2013, Aurelio Cano Flores (alias El Yankee) was sentenced to 35 years in prison for conspiring to import multi-ton quantities of marijuana and cocaine into the United States. Cano Flores, also known as "Yeyo", was a former Mexican police officer and is the highest-ranking Gulf Cartel member to be convicted by a U.S. jury in 15 years.[361]

On 30 June 2019, Mario Alberto Cárdenas Medina, the son of Osiel's brother Mario, was arrested in the state of Mexico.[362][363] He was arrested with a female companion identified as Miriam "M" and is accused of being responsible for recent violence in Tamaulipas[364]

In March 2023, a splinter faction from the Gulf Cartel called the Scorpions Group publicly accepted responsibility for an incident where four Americans were kidnapped, which ended in two of the victims being killed. Following the incident, the gunmen responsible for the kidnapping were reportedly handed over to the authorities and the cartel made a public apology.[365]

In popular culture

In Sicario: Day of Soldado (2018) the CIA framed the "Matamoros Cartel" for killing the antagonist's men to intentionally start a cartel war between rivals.

The Gulf Cartel during the late 1980s and early 1990s era is briefly portrayed in Netflix's Narcos: Mexico series (2018 - 2021) with Mexican actor Jesús Ochoa playing Juan Nepomuceno Guerra and Flavio Medina playing as nephew Juan García Ábrego.

See also

References

- Greig, Charlotte (2006). Evil Serial Killers: In the Minds of Monsters. Arcturus. p. 88. ISBN 9780572030896.

- Smith, Benjamin T. (1 October 2018). "The Mexican Press and Civil Society, 1940-1976: Stories from the Newsroom, Stories from the Street". The University of North Carolina Press - Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data. Westchester Publishing Services. ISBN 9781469638119. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- Newspapers, Mcclatchy (22 April 2009). "Mexican cartels funneling shipments to Italian mafia through Texas". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- "Cocaine Comrades: The Balkan Ties of a Fallen Colombian Drug [Trafficker". 6 December 2021.

- "Monte Escobedo, Zacatecas: Cartel del Golfo Burns Captured Combatants". Borderland Beat. 21 June 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- "La lucha entre 'golfos' y 'zetas' desgarra a Tamaulipas". La Vanguardia. 16 August 2010.

- "El cártel del Golfo echa a Los Zetas de Tamaulipas". Milenio Noticias. 5 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2 August 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "Gulf Cartel". Insight: Organized Crime in the Americas. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- "U.S. AND MEXICAN RESPONSES TO MEXICAN DRUG TRAFFICKING ORGANIZATIONS" (PDF). UNITED STATES SENATE CAUCUS. May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011.

- Beittel, June S. (7 September 2011). "Mexico's Drug Trafficking Organizations: Source and Scope of the Rising Violence" (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- Campbell, Howard (2009). Drug war zone: frontline dispatches from the streets of El Paso and Juárez. University of Texas Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-292-72179-1.

- McCAUL, MICHAEL T. "A Line in the Sand: Confronting the Threat at the Southwest Border" (PDF). HOUSE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- Warner, Judith (2010). U.S. Border Security: A Reference Handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 381. ISBN 978-1-59884-407-8.

- Grillo, Ioan (2011). El Narco: Inside Mexico's Criminal Insurgency. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-60819-504-6.

- Correa-Cabrera 2017, p. 267.

- "Narcotics Rewards Program". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 28 November 2017.

- Peralta González, César (12 July 2001). "Falleció el fundador del cártel del Golfo". El Universal. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- Lira Saade, Carmen (15 March 2003). "La historia del cártel del Golfo". La Jornada.

- "FBI Adds International Drug Dealer to "Most-Wanted" List". National Drug Strategy Network.

- Vindell, Tony (15 October 1994). "Reputed drug lord's brother under arrest". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- Smith, Peter H. (1997). "Drug Trafficking in Mexico". Coming together?: Mexico-United States relations. Brookings Institution Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8157-1027-1.

- Jordan, David C. (1999). Drug politics: dirty money and democracies. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 288. ISBN 978-0-8061-3174-0.

gulf cartel in U.S.

- Weinberg, Bill (2000). Homage to Chiapas: The New Indigenous Struggles in Mexico. Verso Publishers. pp. 371. ISBN 978-1-85984-372-7.

- "At Drug Trial, Mexican Suspect Faces Accuser". The New York Times. 20 September 1996. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- Dillon, Sam (4 February 1996). "Mexican Drug Gang's Reign of Blood". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- "Juan García Abrego – Top Ten Most Wanted Fugitives". TIMES Magazine. 23 June 2011. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010.

- Muñoz, Juan Miguel (16 January 1996). "México detiene y entrega a Estados Unidos a su principal narcotraficante". El País.

- "Mexican "Gulf Cartel" Leader Juan Garcia Abrego Convicted on U.S. Drug Charges". National Drug Strategy Network.

- Fineman, Mark (17 October 1996). "Mexican Drug Cartel Chief Convicted in U.S." Los Angeles Times.

- Fitzpatrick, Laura (23 June 2011). "Juan Garcia Abrego". TIME Special | CNN.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010.

- Abadinsky, Howard (2009). Organized Crime. Cengage Learning. pp. 462. ISBN 978-0-495-59966-1.

gulf cartel.

- Bailey, John J; Roy Godson (2001). Organized Crime and Democratic Governability: Mexico and the U.S.-Mexican Borderlands. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8229-5758-4.

- Harrison, Lawrence E. (1997). The Pan-American Dream: Do Latin America's Cultural Values Discourage True Partnership with the United States and Canada?. Westview Press. pp. 227, 228. ISBN 978-0-8133-3470-7.

- Schiller, Dane (16 January 1996). "Legendary Juan Garcia Abrego in U.S. custody". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- "At Drug Trial, Mexican Suspect Faces Accuser". The New York Times. 20 September 1996. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Tedford, Deborah (2 July 1996). "Garcia Abrego is U.S. citizen, officials insist". The Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Schiller, Dane (19 January 1996). "Expulsion may have broken the law". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Langford, Terri (1 February 1997). "Life in jail for drug lord". The Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Schiller, Dane (17 January 1996). "Juan Garcia Abrego arraigned in U.S. FBI fugitive could spend life in prison". The Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- "UNITED STATES v. GARCIA ABREGO". United States Court of Appeals: Fifth Circuit. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Taylor, Marisa (17 October 1996). "Jury: Abrego guilty". The Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Robbins, Maro (27 August 1995). "Garcia Abrego was allowed to go free". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Schiller, Dane (30 November 1995). "Peña: Garcia Abrego hurt by huge bust Agents seize $22 million load of coke". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Pérez González, Jorge (22 February 2009). "Mentes perversas". Hoy Tamaulipas. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Vindell, Tony (24 January 1996). "El Profe welcomes Garcia Abrego's downfall". The Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Althaus, Dudley (2009). "Texas-Mexico Borderlanconfrontads: The Slide Toward Chaos" (PDF). The International Journal of Continuing Social Work Education. 12 (10974911): 57. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- "Historia y estructura del Cártel del Golfo". Terra Noticias. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Castillo, Gustavo (2 May 2009). "Desplazan a los García Ábrego en liderato del cártel del Golfo". La Jornada.

- Alzaga, Ignacio (1 May 2009). "Relegan a familia de García Ábrego en cártel del Golfo". Milenio Noticias. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011.

- Weiner, Tim (19 January 2001). "Mexico Agrees To Extradite Drug Suspect To California". The New York Times.

- Lupsha, Peter. "A Chronology | Murder, Money, & Mexico". University of New Mexico.

- Medellín, Alejandro (4 February 2011). "Medina Garza en 'La Palma'". El Universal. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- Zendejas, Gabriel. "Detectan a poderoso capo del Cártel del Golfo". La Prensa. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- Ruiz, José Luis (3 April 2001). "Caen 21 miembros de cártel del Golfo". El Universal. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- "Indagan a familiar de El Señor de los Tráileres". Milenio Noticias. 18 November 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012.

- Ramírez, Ignacio (10 April 2000). "La disputa del narcopoder". El Universal. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- "Desde las entrañas del Ejército, Los Zetas". Blog del Narco. 23 May 2010. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010.

- ""Los Zetas" se salen de control". El Universal. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- "DEA: acuerdan 3 cárteles alianza contra Los Zetas". Milenio. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- "¿Quienes son los Zetas?". Blog del Narco. 7 March 2010. Archived from the original on 29 July 2011.

- "Cártel de 'Los Zetas'". Mundo Narco. 15 January 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2011.

- Grayson, George W. (2010). Mexico: narco-violence and a failed state?. Transaction Publishers. p. 339. ISBN 978-1-4128-1151-4.

- Tobar, Hector (20 May 2007). "A cartel army's war within". Los Angeles Times.

- "Los Zetas and Mexico's Transnational Drug War". Borderland Beat. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Los 'grandes capos' detenidos en la guerra contra el narcotráfico de Calderón". CNN México. 6 November 2010. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012.

- "Video Interrogatorio de Jesús Enrique Rejón Aguilar "El Mamito"". Mundo Narco. 5 July 2011. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011.

- "DEA Fugitive: TREVINO-MORALES, MIGUEL". U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012.

- "Heriberto Lazcano Lazcano "El Verdugo"". Blog del Narco. 3 March 2010. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011.

- Ware, Michael (6 August 2009). "Los Zetas called Mexico's most dangerous drug cartel". CNN World. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011.

- Sherman, Chris (25 January 2012). "Texas jury convicts alleged Mexican cartel hit man". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- "Surge nuevo 'narcoperfil". El Universal. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.