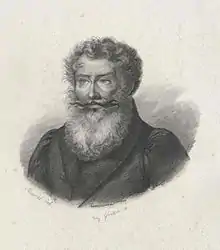

Gustav von Schlabrendorf

Gustav, Count of Schlabrendorf (22 March 1750 – 21 August 1824), described in various sources as a "citizen of the world" ("Weltbürger"), was a political author and an enlightenment thinker. During or shortly before the first part of 1789 he relocated to Paris from where he enjoyed a ringside seat for the unfolding phases of the French Revolution which, initially, he enthusiastically supported. He backed the revolutionary precepts of "Liberty, Equality and Brotherhood". He soon had reason to become mistrustful of the revolution's radicalisation, however, and during the "Terror" ("Terreur") period spent more than 17 months in prison, avoiding a terminal rendezvous with the guillotine only through an administrative oversight. He subsequently wrote several critical works about Napoléon Bonaparte. It was a reflection of his increasingly idiosyncratic lifestyle that by the 1820s he was becoming known as "The Hermit of Paris" (or, in certain more scholarly contemporary sources, "Eremita Parisiensis"): he was happy to endorse the soubriquet, on occasion using it to describe himself.[1][2][3][4]

Gustav von Schlabrendorf | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Richard Gustav von Schlabrendorf(f) 22 March 1750 |

| Died | 21 August 1824 (aged 74) |

| Alma mater | Halle |

| Occupation(s) | Enlightment philosopher Writer Critic-commentator |

| Notable work | "Napoleon Buonaparte and the French People under his Consulate" ("Napoleon Bonaparte und das französische Volk unter seinem Konsulate") |

| Spouse | none |

| Parent(s) | Ernst Wilhelm von Schlabrendorf (1719 – 1769) Anna Carolina von Otterstaedt (1727 – 1784) |

Life

Provenance and early years

Richard Gustav von Schlabrendorf(f) was born in Stettin, at that time a recovering war-ravaged port city in the Prussian Province of Pomerania (and since 1945 a Polish city known internationally by its Polish-language name as Szczecin). He was the third son of Ernst Wilhelm von Schlabrendorf by his marriage to Anna Carolina von Otterstaedt, from the aristocratic Dahlwitz family. The two families had been close for a number of generations. Soon after Gustav's birth, his father was appointed First Minister of Silesia. As a result of the promotion the family moved, in 1755, to the Silesian capital, Breslau (as Wrocław was known at that time). The job of integrating the prosperous and recently annexed Silesian territories into the Kingdom of Prussia was a major challenge, but it was one for which Ernst Wilhelm von Schlabrendorf was apparently well rewarded in various ways. On 20 March 1763 the king made him a special gift of 50,000 Thalers. By the time he died in 1769 his family was, by the standards of the time and place, conspicuously wealthy. Gustav von Schlabrendorf spent most of his childhood in Silesia. He received a thorough and comprehensive schooling from tutors and then, in 1767, moved on to Hochschule (university) level education in Frankfurt am Oder where he remained till 1769. Between 1769 and 1772 he continued his studies at Halle. He had enrolled to study Law, which would have provided a conventional preparation for a career in public administration. Gustav von Schlabrendorf, however, interpreted his curricular opportunities more widely, studying ancient and Modern Languages along with Philosophy and the Arts.[1] He was also drawn to Freemasonry which had arrived in Prussia from England and Scotland earlier that century. In 1777 he was accepted into the "Minerva zu den drei Palmen" ("Minerva of the three palm trees") lodge in Leipzig.[5]

Travels

His father's death at the end of 1769 left Gustav von Schlabrendorf well provided for. Since 1766 he had also been receiving income from a benefice in Magdeburg which his father had set up for him back in 1753. He could therefore afford to broaden his education with a succession of lengthy trips across the German lands, the Swiss Confederacy, France and England. In the end he based himself in England for six years. He was, in particular, intrigued and impressed by the uniqueness of the country, by its constitutional structure, its highly developed industries and, not least by its philanthropic institutions based around its national church For some of his time in England he was accompanied by the distinguished anglophile aristocrat, Baron vom Stein. During this period he also established what would become a long-lasting friendships with the enlightenment philosopher, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi.[1][5] and the radical old-Etonian polemicist Horne Tooke.[3]

Paris

Shortly before the outbreak of the French Revolution von Schlabrendorf relocated to Paris. He took a room in the "Hôtel des Deux Siciles" to which his carriage driver had delivered him. As matters turned out this hotel would become his home for the next thirty years.[5] Several high-profile French intellectuals associated with the enlightenment ideals underpinning the unfolding revolution which von Schlabrendorf anticipated with enthusiasm became personal friends. These included the Marquis de Condorcet, Louis-Sébastien Mercier and Jacques Pierre Brissot.[5] (Two of these three would be dead by the end of 1795.) In addition, he quickly became a part of the network of politically aware German expatriates living in the city. Among these exiled democrats and revolutionaries were the writer-polymath Georg Forster, the Schwabian physician and commentator Johann Georg Kerner, the political journalist from Silesia, Konrad Engelbert Oelsner and more briefly, the youthful revolutionary Adam Lux. Von Schlabrendorf was older and richer than most of the others: he tended to take a lead in offering advice and looking after the material needs of his German radical friends in Paris.[1][4]

Victim of the revolution

Gustav von Schlabrendorf greeted the outbreak of the French revolution as "die Erlöserin des rein Menschlichen" (loosely "the salvation of all humanity").[6] His circle greeted the Storming of the Bastille with enthusiasm. Government, especially in Bourbon France, was out of touch with the increasingly prevalent enlightenment precepts in which they believed. However, as the revolution unfolded on the streets of Paris the "moderate" revolutionaries found themselves marginalised after the Girondins were replaced by better organised Jacobin hardliners. Gustav von Schlabrendorf and his circle found themselves under intensifying suspicion. In the summer of 1793 von Schlabrendorf was arrested. At about the same time he broke off his brief but passionate engagement with Jane, the sister of the Scots-born reformist Thomas Christie.[1][7] In prison he found that the inmates divided into "two classes of men: men of rank and foreigners". Determined to keep a low profile, he "shunned the former and associated wholly with the latter", attempting to be identified as a sort of transnational member of the revolutionary "Sans-culottes" faction.[3] He continued to be a generous benefactor to needy friends and fellow inmates.[3] He was able to entrust his wealth to Oelsner, who had been able to avoid imprisonment and probable execution by escaping to Switzerland Oelsner was now able to conserve von Schlabrendorf's property and, later, to return it despite his own financial difficulties. Meanwhile von Schlabrendorf awaited his execution with evident equanimity. Various reports later surfaced as to how he managed to avoid death at this stage: the most colourful contends that on the morning when his name appeared on the list of prisoners to be placed on the cart for transportation to the guillotine he was unable to find his shoes.[3][8] According to the anecdote that later emerged, on account of this difficulty his jailor agreed that it was unreasonable that he should be executed without his boots on his feet, and he was accordingly left off that day's cart, in order to be taken with the next day's batch for execution instead.[3] However, on the next day, as he awaited the call, duly prepared and booted, his name was not called.[3] His execution had evidently been forgotten, and although he feared being summoned for death each day thereafter, in the end he was able to leave the prison alive.[8] That happened only after the fall of Robespierre, at which point a large number of surviving detainees were released. Gustav von Schlabrendorf, who by this time had been imprisoned for almost eighteen months, now returned to his room at the "Hôtel des Deux Siciles" in the fashionable Rue de Richelieu, where he would live out the rest of his life.[1][5]

A Paris Diogenes

Even though from now on he showed a growing reluctance ever to leave his hotel, von Schlabrendorf quickly resumed his role as a support and focus of intellectual ideas, both through face to face discussion and through his habit of making generous financial provision to those who turned to him whether they deserved it or (in the view of at least one biographer) not.[1] In his city-centre hotel room he himself led an existence of bizarre austerity. His increasingly eccentric lifestyle led to him being described by friends and admirers as a "Parisian Diogenes" ("Diogenes von Paris"),[5] a soubriquet which according to some observers he rather liked. He was also a regular letter writer. Letters survived, which is one of several reasons that he made a major contribution to the detailed knowledge and understanding of the French revolution across Germany as the nineteenth century progressed towards a more democratic future. That was important because German reformers and revolutionaries who set forth their proposals in 1848, not just in 1848 but also during the decades that followed, drew much of their understanding of the French revolution from the writings of Gustav von Schlabrendorf.[2][4]

Women

Unusually for those times, but significantly in the context of twentieth century developments, many of his interlocutors and correspondents were women. One who has left a particularly large footprint in history for English-language readers was Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), like him an enthusiastic backer, at the outset, of the French revolution who at the end of 1792 came to Paris in order better to understand what was happening.[9] She quickly came into contact with von Schlabrendorf's circle of mainly foreign-born intellectuals during the period of more than two years that she spent in Paris.[10] According to one of Wollstonecraft's biographers "the rich Silesian Count von Schlabrendorff ... was living 'on almost nothing' in order to avoid adverse comment on his wealth".[9] Subsequently von Schlabrendorf would recall her "charming grace ... [and face] ... full of expression.... There was enchantment in her glance, her voice and her movement.... [She was] the noblest, purest and most intelligent woman I ever met".[9] A [female] biographer quoting von Schlabrendorf's reaction also points out that he was "a susceptible man and was [at the time]... engaged to Jane Christie".[9] Indeed there were famously plenty of men who were charmed by Mary Wollstonecraft, and no doubt there will have been other woman to whom von Schlabrendorf was attracted. But there is no record that large numbers of women visited him during his eighteen months in prison awaiting the guillotine: according to an entry in Wilhelm von Humboldt's diaries, Mary Wollstonecraft often did.[6][11]

Long war

He was constantly troubled by the erosion of his hopes, and those of his friends, in the positive power of the revolution, and devoted much energy and resource to charitable and humanitarian ventures. A devout protestant, he backed a bible society and the protestant minority more generally, committing resources to the education and welfare of the poor.[11] Meanwhile he took a lively interest in events back in his homeland. Prussia was under sustained attack from the French revolutionary armies. After Napoleon's successful power grab in 1799 the French military machine became increasingly effective. In 1806 the Prussian government would be forced to abandon Berlin. The king took refuge in East Prussia. Meanwhile, in Paris von Schlabrendorf spent generously to improve the conditions of compatriots who had been taken prisoners of war by French troops. In 1803 he received an "invitation" from the Prussian government to return "home" to Silesia, since he was Silesian vassal [of the King of Prussia]. When he failed to comply he was threatened with confiscation of his substantial Silesian landholdings. The confiscation was then formally enacted, on 7 September 1803, by means of a confiscation decree enacted by the Silesian authorities, based at this stage in Glogau on account of the disruption caused by the war.[1] Wilhelm von Humboldt's diaries report that throughout this time he paid close attention to current issues and developments, engaging constantly in intense political discussions, providing inspiration, and endlessly displaying to friends and visitors alike a singular flair for finding unexpected counter-arguments.[3][11]

Confiscations

In Silesia, despite the order to confiscate von Schlabrendorf's lands having come into effect, there are signs that at least some in the government were keen to minimise unpleasantness. A letter dated 3 November 1803, from Count Hoym, the Prussian Minister for Silesia,[12] urged von Schlabrendorf to lose no time in visiting his homeland, even if he would only stay for four weeks, in order to demonstrate his respect for The king's wishes.[lower-alpha 1] The letter concludes with a personal postscript: "I repeat my very simple request. Take care for your own interests and make then small sacrifice of a brief change in your usual lifestyle."[1][lower-alpha 2] But Schlabrendorf remained unmoved, pleading ill-health. Nevertheless, following intercessions made on his behalf, the authorities decided to substitute a temporary sequestration of his property. The Prussian ambassador in Paris, Girolamo Lucchesini, was mandated to visit von Schlabrendorf to plead with him to accede to the request that he return, if only briefly, to Silesia. A meeting took place in February 1804, but von Schlabrendorf had by now, he indicated, become convinced that the entire matter resulted from family intrigues orchestrated by his relatives, and again refused to leave Paris. Later that year, during the summer, von Schlabrendorf persuaded the Prussian authorities that he really was keen to return home, but he made a plea that he might be granted a further brief deferral. The king was reportedly persuaded, and on 26 August 1804 granted a six week extension. Somehow at the end of the six week period Gustav von Schlabrendorf was still in Paris, however. One source, possibly having regard to something von Schlabrendorf himself subsequently asserted, indicates that he wanted to return to his homeland and take part in the wars of liberation in his homeland but did not receive the necessary exit documentation from the French authorities.[5] In 1805 matters became more serious, when the Prussian authorities deprived him of the benefice income he had been receiving from Magdeburg since 1766. He had, in fairness, not been diligent in fulfilling his benefice commitments. By a cabinet decree of 24 September 1805, the lifting of the sequestration of his Silesian land was made expressly conditional upon his returning "home". Still von Schlabrendorf was unmoved, his own lifestyle being frugal, but he was nevertheless concerned that he was no longer able to be as generous as before to others.[1]

Following a succession of crushing military defeats the Treaties of Tilsit in July 1807 left Prussia much diminished territorially. A massive monetary "tribute" was also levied. French armies had captured Berlin the previous year, forcing the Prussian king to move the court to Königsberg. Nevertheless, Prussia still had an army which enforced a measure of respect among the great powers, and towards the end of 1807 the king's younger brother, the soldier-diplomat Prince William arrived in Paris on a mission to try and persuade the emperor to ameliorate the terms imposed at Tilsit. The size of the "tribute" levied on Prussia was indeed reduced in 1808, though opinions differ over how far this represented a personal achievement by Prince William. For Gustav von Schlabrendorf Prince William's time in Paris was certainly not wasted. The prince was accompanied to Paris by the celebrity-polymath Alexander von Humboldt who had recently returned from a five year trip through "the Americas". Von Humboldt was, like von Schlabrendorf, a committed letter writer, and the two were friends. It was arranged that Gustav von Schlabrendorf, who was evidently incentivised by the prospect of meeting the king's brother to leave his hotel room, should be presented to the prince. The prince was greatly entertained and charmed by this erudite Prussian: during his stay in Paris, von Schlabrendorf became a frequent guest at the prince's table. Von Schlabrendorf was able to use his new friendship with the king's younger brother to have the confiscation of his Silesian states revoked.[1]

On Napoleonic France and Europe

Gustav von Schlabrendorf's best known work, which appeared - initially without attribution - in 1804 was entitled "Napoleon Buonaparte and the French People under his Consulate" ("Napoleon Bonaparte und das französische Volk unter seinem Konsulate"). Longer than a political pamphlet but shorter than many books of the period, for a long time the powerfully written criticism was widely, if incorrectly, attributed to the musician Johann Friedrich Reichardt, another disillusioned former backer of the revolution who by this stage was making no secret of his hostility to the Bonapartist régime. It was indeed von Schlabrendorf's friend, Reichardt who smuggled the manuscript out of France and saw to its publication.[3]

Gustav von Schlabrendorf, who once had so admired the French revolution seemed to have become an uncompromising francophobe during the intervening fifteen years, leading one biographer to puzzle over his reluctance to return to Silesia. Taking some of the observations in this publication at face value, one can be driven to conclude that there was nothing to keep him in Paris apart from inertia driven by a powerful disinclination to submit to changes in his routine.[1] The French, he wrote, were a fundamentally rotten nation (...eine "grundausverdorbene" Nation) characterised by a complete return to "the great all-consuming tyranny of sensuality and egotism in the heart of every individual [which] renders all laws powerless and ineffective".[1][lower-alpha 3]

There were good reasons why von Schlabrendorf might have been hesitant about acknowledging authorship of the work. According to several commentators, von Schlabrendorf's "open criticism of Napoleon" triggered no adverse consequences [in Paris] because the authorities did not regard this quirky eccentric as a serious opponent.[5] The failure of the French censors to take him seriously may very well have saved his life. The fact that Schlabrendorf wrote and voiced his opinions chiefly For German expatriates and readers, using the German language, while censors based in Paris and the public opinion for which they cared tended to be affected primarily by what was uttered and written in French, was no doubt also a factor. On the far side of the Rhine his published views on Napoleon's actions drew plenty of attention. The book's German readers, including Goethe,[lower-alpha 4] Karl Böttiger and Johannes von Müller[13][14] were confronted — in many cases for the first time — with a book written in Paris, at the heart of the Napoleonic project, that uncompromisingly insisted that far from promoting the democratic development of Europe, Napoleon was in the process becoming a major threat. Several further editions quickly appeared in both German and English.[3] The book was a sensation with readers because of the way in which, as early as 1804, it exposed the brutality of the authoritarian Napoleonic tyranny, even before the relaunch of his régime as the French Empire in May 1804. Between the book's appearance during 1804 and Napoleon's fall ten years later, von Schlabrendorf's warnings proved prescient. In the characteristic phraseology of von Schlabrendorf's biographer, Karl August Varnhagen von Ense, von Schlabrendorf's trenchant opinions were "like a shining meteor in a politically gloomy sky of that time".[lower-alpha 5][15]

It was also in 1804 that he produced his "Letter to Bonaparte". The tone was even more shrill, though the text was again in German. The 65 page unattributed "letter" was sent, it said, from "one of [the emperor's] formerly most ardent supporters in Germany". On the title page, where normally the author, printer and/or publisher would have been identified, was written simply "Deutschland, Anfangs Juny, 1804" ("Germany, early June 1804"). In it von Schlabrendorf condemned Napoleon's hypocrisy and murderous cruelty:

- "Are you so delusional as to think that Europe and France do not see through your 'love of justice', whereby you seek to deceive but also to save your own skin? The raw butchery of the Maroccan power broker, at his personal whim hacking the heads off his subjects, each of whom has so much more honour than a wretchedly hypocritical European government, which has already condemned them with the slime of its quasi-judicial outpourings. ... Hey, just get on with your killing! It will serve your perverted ends better than all this intolerable hypocrisy".[16][17][lower-alpha 6]

More eccentric yet

- "There was also the famous Paris expatriate, Count Schlabrendorf, in whose sepulchral room the great social earthquake was left to unfold in a vast global tragedy; uncontested, contemplated, evaluated and not infrequently tweaked. Intellectually he stood so high above everyone else that he could at any time clearly see through the significance and direction of the intellectual battle, without being touched by all their muddying noise. This magisterial prophet arrived on the wider stage when he was still a young man, and the catastrophe had barely played out by the time his raddled beard had reached down to his belt."

- "So auch der berühmte Pariser Einsiedler Graf Schlabrendorf, der in seiner Klause die ganze soziale Umwälzung wie eine große Welttragödie unangefochten, betrachtend, richtend und häufig lenkend, an sich vorübergehen ließ. Denn er stand so hoch über allen Parteien, daß er Sinn und Gang der Geisterschlacht jederzeit klar überschauen konnte, ohne von ihrem wirren Lärm erreicht zu werden. Dieser prophetische Magier trat noch jugendlich vor die große Bühne, und als kaum die Katastrophe abgelaufen, war ihm der greise Bart bis an den Gürtel gewachsen."[18]

Following the publication of his attacks on Napoleon, von Schlabrendorf's behaviour became, year by year, more idiosyncratic than ever. Several more German-language passionate diatribes against Napoleon were published, and it may reflect von Schlabrendorf's growing awareness of the threat of arrest that he took greater care than before to conceal his authorship. In his 1806 offering "Napoleon Buonaparte wie er leibt und lebt und das französische Volk unter ihm" (loosely, "Napoleon Buonaparte: how he lives and how the French people live under him") - ostensibly published in "Petersburg" by an unidentified publisher and, again, scripted by an unidentified author - he used the Corsican spelling of the emperor's name which might have been a quiet device for emphasizing Napoleon's non-French provenance and may also have been an attempt to distance the publication from others that he had recently had published.[3] In a further subterfuge the book was described as a "translation from the English" though in fact, when the English version did appear, it was a translation from the German original text undertaken by von Schlabrendorf's East Anglian friend, the lawyer diarist Henry Crabb Robinson.[3] In any event, the French authorities had already concluded that von Schlabrendorf was "more mysterious than alarming" and the French censors still failed to pounce.[3]

His hotel room continued to be a focus for German and French intellectuals, artists and diplomats, but the occupant's quirky habits and absence of personal hygiene began to feature in letters and reports from some of his visitors, along with speculation as to whether or not he ever bothered to wear any appropriate undergarments.[1][3][5] His beard simply grew and grew. Alexander von Humboldt would recall, in a letter to his brother, that during his later years Gustav von Schlabrendorf would eat nothing except fruit.[5] Nor, it would appear, did he waste money on heating his room. "That overcoat is undoubtedly still the one that we knew in the last century", confided Wilhelm von Humboldt after a visit to the "Hôtel des Deux Siciles" in 1813.[19] Von Humboldt's relationship with von Schlabrendorf may have been affected by the fact that Caroline von Humboldt, his wife was (and is) widely believed to have been Gustav von Schlabrendorf's mistress since as early as 1804.[20] (Wilhelm and Caroline von Humboldt operated what was, even by the standards of those times, a famously "open" marriage.[20])

Fame

By the time allied armies took Paris in March 1814 Gustav Schlabrendorf's authorship from Paris of a series of German-language polemical yet scholarly anti-Napoleon books and tracts was no secret. In Prussia and the westerly German speaking lands that had been part of the French empire till 1813 he was something of a celebrity. The advancing Prussian forces greeted him with enthusiasm and the invitation to return "home" to Prussia was renewed. (However, somehow he was unable to obtain the necessary travel documents.) After the coalition armies entered Paris, it is reported that the assistance he rendered the military was so important that The king awarded him the (recently inaugurated) Iron Cross.[1]

Later years

After the Napoleonic Wars ended, Gustav con Schlabrendorf lived on for nearly ten years, as far as visitors could tell under ever more reduced circumstances, any available funds being spent on scholarship or charity. He nevertheless remained in the city-centre "hermitage" he had created for himself over the previous twenty years. Paris had become an international city: there were more visiting foreign diplomats and politicians, writers and artists, Germans and Frenchmen. His pungent book-lined hotel room was busier than ever. Many sought advice. Some sought and received "financial support". According to a recollection attributed to his friend Konrad Engelbert Oelsner, at one point, surrounded by his books and manuscripts, he remained in his hotel room without a break for nine years.[lower-alpha 7] He frequently renewed his assurances that he intended to come "home" to Prussia, but that never happened. Inertia prevailed.[1] His recurring mistress, Caroline von Humboldt, had named one of the von Humboldts' eight recorded children after him back in 1806[lower-alpha 8] and remained a regular visitor and companion ten years later. She would later describe Gustav von Humboldt as "simply the most human human being I ever knew"[lower-alpha 9][22]

In the aftermath of the war, with his Silesian estates restored to him, von Schlabrendorf was able to resume his generous giving to friends in need, prisoners of war rendered destitute and other good causes, but it is not clear that his fortune held out for as long as he did. During his final few years he set out to try and crystallise his ideas on paper: the focus was increasingly on his writing. He engaged intensively on creating a "general languages" teaching theory and on etymological studies more broadly.[6] This never led to any published conclusions, but traces of his theories and conclusions found their way into the public realm via papers and books produced subsequently by his friends.[1][6]

During the summer of 1824 Gustav von Schlabrendorf fell seriously ill. With great difficulty his doctor succeeded in prising him away from his hotel room and he moved to Batignolles which at that time was a country village to the north of the city. The purpose of the move was to enable his health to benefit from the clean country air. However, the move came late in the day, and on 21 August 1824 he died at Batignolles. His final big project had involved collating his writings concerning the French revolution. He intended to bequeath this to a Prussian university. A will setting forth his intentions had been prepared but, not for the first time in the life of Gustav von Schlabrendorf, stated intentions had not been followed through: the legal requirements for validation of the document had not been completed. When he died his most recent valid will dated from 1785, and his death was followed by disputatious exchanges between his relatives even though, apart from his books and papers, he had managed to die bereft of worldly assets. The Prussian embassy had to pay most of the costs associated with his funeral.[1][6] His papers were sold off: the whereabouts of most of them is unknown.

Afterlife

His body was buried at the "Père Lachaise Cemetery" (as Paris's largest cemetery has subsequently become known). Some time later the remains were moved to the "Chemin Bohm" cemetery and reinterred close to the tomb of the Prussian soldier-ambassador Heinrich von der Goltz (1775 – 1822). There (in 2019) they remain. The main tombstone was removed sometime around 1900 but parts of the grave's stone surround can still be seen and the grave plot has not yet been recycled.[6]

Notes

- "...auf eine ganz kurze Zeit, wenn auch nur auf 4 Wochen, sein Vaterland zu besuchen, um dadurch seine Achtung gegen den Willen des Königs an den Tag zu legen."[1]

- "Ich wiederhole meine ganz einfache Bitte“, schließt der Minister, „das Wohl der Ihrigen zu beherzigen und diesem das kleine Opfer einer kurzen Veränderung Ihrer gewohnten Lebensweise zu bringen."[1]

- "...die große Alles verschlingende Tyrannei der Sinnlichkeit und des Egoismus in dem Herzen jedes Einzelnen alle Gesetze entkräftet und vernichtet".[1]

- Goethe indeed reviewed "Napoleon Bonaparte und das französische Volk unter seinem Konsulate" for the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. He identified a "certain tendentiousness" in it. Other readers were evidently more easily persuaded, especially as the French empire expanded and consolidated.[3]

- "...zu seiner Zeit am trüben politischen Himmel wie ein Lichtmeteor erschien".[15]

- "Wähnst Du, Europa und Frankreich durchschauen nicht Deine pfiffige Gerechtigkeitsliebe, womit Du zu täuschen, im Grunde aber auch nur Dich und Deinen Leib zu sichern suchst? Die rohen platten Metzeleien des maroccanischen Machthabers, der nach Lust und laune seinen Unterthanen selbst die Köpfe abhakt, ist in der That viel achtbarer, als die elende Heuchelei einer europäischen Regierung, die den schon voraus Verurtheilten, noch mit ihrem juristischen Schleim einspinnt. (...) Ei, so morde kurzweg! Es wird Dir besser frommen, als das unerträgliche Heucheln."[16][17]

- "Einen Umstand [habe ich] außer Acht gelassen, nämlich den, daß Graf Schlabrendorff neun Jahre lang nicht von seinem Zimmer gekommen ist. Schon zu Ende 1814 fing er an einzusitzen.[21]"

- Sadly, Gustav von Humboldt (7 Januar 1806 – 12 November 1807) died in early infancy.

- "...den menschlichsten Menschen, den ich je kannte."[22]

References

- Colmar Grünhagen (1890). "Schlabrendorf: Gustav Graf v. S., philanthropischer Sonderling, 1750 bis 1824". Allgemeine deutsche Biographie. Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, München. pp. 320–323. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Hellmut G. Haasis (10 April 1992). "Betrogene Liebe". Der "Anti-Napoleon": Hans Magnus Enzensbergers schlampige Edition (book review). Die Zeit (online). Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Philipp Hunnekuhl. "Literary transmission, exile and oblivion: Gustav von Schlabrendorf and Henry Crabb Robinson" (PDF). Litteraria Pragensia: Studies in Literature and Culture. Charles University, Faculty of Arts Press, Prague. pp. 47–59. ISSN 0862-8424. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Hans Hoyng (26 January 2010). "Der Salon des Grafen". Ein Adliger aus altem märkischem Geschlecht diente als Pariser Nachrichtenbörse für revolutionsbegeisterte Deutsche. Viele kamen nach Frankreich, um zu lernen, wie sie die Heimat befreien könnten. Der Spiegel online (SPIEGEL GESCHICHTE 1/2010). Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Alexander Süß (November 2011). "Richard Gustav Graf von Schlabrendorf (1750-1824): Kosmopolit - Publizist - Exzentrike" (PDF). Minerva zu den drei Palmen e.V., Leipzig. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- "Gustav Graf von Schlabrendorf". Omnibus salutem!. Klaus Nerger (Schriftsteller CXLV), Wiesbaden. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Rachel Hewitt (5 October 2017). Neck or nothing. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-84708-575-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Karl August Varnhagen von Ense (1847). Footnote: Gustavus Count von Schlabrendorf ... pp. 193–194.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Janet Todd (30 July 2014). How silent is now Versailles!. pp. 225–226. ISBN 978-1-4482-1346-7. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Gisela Müller (1 March 2011). "Gelebte Gleichberechtigung vor 200 Jahren? Caroline und Wilhelm von Humboldt nach Hazel Rosenstrauch, Wahlverwandt und ebenbürtig" (PDF). Literarische Gesellschaft Lüneburg e.V. p. 19. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Dirk Grathoff. Kleists Geheimnisse: Unbekannte Seiten einer Biographie.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Carl Eduard Vehse (1851). Geschichte der deutschen Höfe seit der Reformation. Hoffmann und Campe. pp. 245–246.

- Friedemann Pestel (2009). Kulturtransfer. Die Emigranten und das Ereignis Weimar-Jena. pp. 142–257. ISBN 978-3-86583-423-2. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Sylvia Böning (6 May 2013). "Erste Deutschlandreise 1803/1804". Weiblichkeit, weibliche Autorschaft und Nationalcharakter.Die frühe Wahrnehmung Mme de Staëls in Deutschland (1788–1818). Philosophische Fakultät der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena. pp. 112–153. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Karl August Varnhagen von Ense: Graf Schlabrendorf, amtlos Staatsmann, heimathfremd Bürger, begütert arm. Züge zu seinem Bilde. In: Historisches Taschenbuch (Friedrich von Raumer, Hrsg.). Dritter Jahrgang, Leipzig 1832, pp. 247–308.

- Sendschreiben an Bonaparte. Von einem seiner ehemaligen eifrigsten Anhänger in Deutschland. June 1804.

- Gustav von Schlabrendorf (1804). Sendschreiben an Bonaparte. publisher not identified. pp. 51–52.

- Joseph von Eichendorff; Joseph Kürschner (series editor-compiler); Max Koch (producer-editor) (1857). Deutsches Adelsleben am Schlusse des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts .... Erlebtes. pp. 19, 5–27.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help);|work=ignored (help) - Dagmar von Gersdorff: Caroline von Humboldt. Eine Biographie. Berlin 2013, p. 75.

- Carola Muysers (15 April 2016). "Berlin-Women: Caroline von Humboldt (23.02.1766-26.03.1829) Networkerin und Kunstmäzenin". Berlin-Woman. Bees & Butterflies. Agentur für kreative Unternehmen. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- An unattributed report in: Preußische Jahrbücher vol. 1, 1858, p. 85.

- Dagmar von Gersdorff: Caroline von Humboldt. Eine Biographie. Berlin 2013, pp. 75, 116–118.