HMS Greyhound (1780)

HMS Greyhound was a cutter that the British Admiralty purchased in 1780 and renamed Viper in 1781. Viper captured several French privateers in the waters around Great Britain, and took part in a notable engagement. She was sold in October 1809.

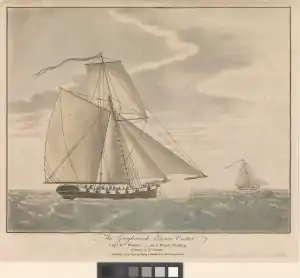

The Greyhound Excise Cutter. Capt Wm Watson - on a wind, chasing[1] | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Greyhound |

| Acquired | 23 June 1780 (by purchase) |

| Renamed | HMS Viper (1781) |

| Honours and awards | Naval General Service Medal with clasp, "29 July Boat Service 1800"[2] |

| Fate | Broken up July 1848 |

| General characteristics [3] | |

| Type | Cutter |

| Tons burthen | 148 (bm) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Sail plan | Schooner |

| Complement | 60 |

| Armament |

|

Anglo-French War

Greyhound was commissioned in June 1780 under Lieutenant Richard Bridge for the Scilly Isles and Irish Sea.[3][4] As Viper, she was in company with Nemesis on 3 January 1781 when they captured the Dutch vessel Catherine.[5] Viper was under the command of Lieutenant Thomas Dickinson.[6] Then in August, Stag and Viper were in company when they recaptured the sloop Peggy and the cutter Hope.[7]

On 16 April 1782, Viper captured the French privateer Brilliant.[6] Later that month, on 28 April, Viper and the brig Antigua brought into Waterford a French privateer lugger and her prize. The prize was a sloop that had been sailing from London to Cork with merchandise when the privateer took her.[8]

Lark and Viper were in company on 22 June when they sighted a cutter off Land's End. They gave chase and by 1 p.m. they caught their quarry. She proved to be the Dutch privateer Sea Lion (or Zeuwsche Water Leuw), of Flushing, but out of Cherbourg. Sea Lion had a crew of 50 men, and was pierced for 12 guns, but was only carrying eight 3-pounders. During this cruise she had taken a sloop between Lyme and Weymouth.[9][lower-alpha 1]

Viper was paid off in June 1783, but immediately recommissioned again under Lieutenant Arthur Webber for the Irish Sea.[4] Lieutenant John Crymes took command in 1784 for Land's End and the Irish Sea.[4] In 1785-86 Viper was off Milford on Sea.[10] She was paid off in August 1786. In January of the next year she was again recommissioned for the Irish Sea,[3] again under Crymes's command,[4] and in July was at Lundy.[11] From 1788 to 1789, she was under the command of Lieutenant S. Rains.[4]

She was recommissioned in November 1791 under Lieutenant Robert Graeme for the Irish Sea, and he remained in command until late 1793. In June Viper and Graeme were at Plymouth.[12]

French Revolutionary Wars

In October 1793 Lieutenant John Pengelley (or Pengelly) assumed command.[3]

France invaded the Netherlands in January 1795. On 19 January 1795, one day after stadtholder William V of Orange fled to England, the Bataafse Republiek (Batavian Republic) was proclaimed, rendering the Netherlands a unitary state. From 1795 to 1806, the Batavian Republic designated the Netherlands as a republic modelled after the French Republic. On 20 January 1795, the Royal Navy seized several Dutch war and merchant vessels then at Plymouth. The British position was that the ships were not prizes, but were being held in trust for the stadtholder. until formally seized a year or so later. The naval vessels were the Zeeland (64 guns), the Brakel (54 guns), the Tholen (36 guns), the brig Pye, the sloop Mierman, and the cutter Pye. In addition, there were seven homeward and two outward bound Dutch Indiamen, and from 50 to 60 merchant vessels, all lying in Plymouth Sound. The ships were ordered round to Hamoaze where, after landing their powder, they were allowed to keep their colours flying. In time, the vessels became prizes. All the British vessels at Plymouth on 20 January 1795, including Viper, shared in the prize money arising from the seizure.[13]

In October 1796 Dryad captured the French privateer Vautour. The letter transmitting Captain Beauclerk's letter remarked that Viper and Hazard had twice chased Vautour off the coast.[14]

Nuestra Señora de la Piedad

On 13 March 1797, Pengelley and Viper were about seven leagues north-west from Alboran, as they were returning to Gibraltar from Algiers when she sighted a Spanish privateer. As they approached, Pengelley fired a gun, which the Spaniard answered, first with a shot and then a broadside after he hove to. At half-past one Viper closed alongside the brig. The ensuing action lasted until 3:10 p.m., when the Spaniard hauled down his colours. During the action, the Spanish several times attempted to start fires on Viper by throwing over flasks filled with powder and sulphur.

The Spanish brig was Nuestra Señora de la Piedad. She was armed with six 4-pounder and four 6-pounder guns, and eight swivels, and had a crew of 42 men. The two vessels were thus relatively evenly matched. Nuestra Señora de la Piedad had one man killed and seven dangerously wounded, one of whom died; Viper suffered no casualties.[15]

In 1799, Viper visited Sierra Leone, leaving on 1 April in company with Triton,[16] and returning on 3 August. Pengelly reported that he had run down the coast and found the settlements very healthy.[17]

Viper and Furet

On 26 December 1799, at 10:15 a.m. Viper was seven or eight leagues south of the Dodman, serving as escort to a convoy of three merchant vessels, a sloop, a brig, and a three-masted ship,[18] when she sighted a suspicious vessel sailing towards her. Realising that the approaching vessel was an enemy, Pengelley sailed towards him. The French captain thought that Viper was maneuvering with such timidity that he could prevail.[18] The engagement commenced at 10:45 a.m. The close action continued for three-quarters of an hour, when casualties on board the privateer caused the majority of the crew of the privateer to panic, forcing the captain of the enemy vessel to take flight.[18] A running fight of an hour and a half ensued as Viper pursued her opponent. Eventually, Viper got close enough to be able to pour two broadsides into her enemy, who then struck his colours.[19]

The enemy turned out to be the French privateer Furet, of fourteen 4-pounder guns and 57 men under the command of Citizen Louis Bouvet. Furet was two days out of Saint Malo and had earlier that day put a seven-man prize crew aboard a vessel that she had taken. In the battle with Viper, Furet had four men killed and her first and second captains and six men wounded, four dangerously;[lower-alpha 2] Viper had one man wounded, with Pengelley also being slightly injured. Because both captor and captive were much damaged in their sails and rigging, Pengelley put into Falmouth, from where he intended to sail to Plymouth as soon as he could.[19] The French wounded were transferred to the hospital of Mill Prison. Some weeks later the British paroled Bouvet and sent him in the cartel John to Morlaix.[18]

This was a sufficiently notable single-ship action that in 1847, the Admiralty awarded the Naval General Service Medal with clasp "Viper 26 Decr. 1799" to the one surviving claimant from the action.[20]

Morbihan

In March 1800 Lieutenant Matthew Forester replaced Pengelley.[3] Viper joined Sir Edward Pellew's squadron at Morbihan on 5 June,. Then on 6 June, the boats of the squadron attacked Morbihan itself. The British were able to cut out five brigs, two sloops, and two gun vessels, and to capture 100 prisoners. The British burned the corvette brig Insolente, of 18 guns, as well as several small craft. They also destroyed the guns there and blew up the magazine.[21] On 27 June Viper was in company with Excellent when they recaptured Lord Duncan.[22]

Because Viper was part of Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren's squadron, her crew was entitled to share in the proceeds from the squadron's recapture of Lancaster on 28 June.[23] Similarly, Viper shared in the proceeds of Vigilant, Menais, Industry (salvage for recapture), wreck of a vessel sold, Insolent, and Ann.[23] Lastly, she shared in the squadron's capture of the French privateer Guêppe on 30 August.[24][lower-alpha 3]

Cerbère

At some point in mid-1800, Lieutenant Jeremiah Coghlan (acting) assumed command. In July 1800, Coghlan, who had been watching Port-Louis, Morbihan, proposed to Pellew that he, Coghlan, take some boats into the harbour to cut out one of the French vessels there. Pellew acceded to the proposal and gave Coghlan a cutter from Impetueux, Midshipman Silas H. Paddon, and 12 men. Coghlan added in six men and a boat from Viper, and a boat from Amethyst. On 29 July the boats went into the port after dark, targeting a brig. During the run-up to the attack the boats from Viper and Amethyst fell behind, but Coghlan in the cutter persisted.[25]

Coghlan's initial attempt at boarding failed and he himself received a pike wound in the thigh. The French repelled a second attempt too. Finally, the British succeeded in boarding, killing and wounding a large number of the French brig's crew, and taking control. The two laggard boats came up and the British then brought the brig out of the harbour and back to the fleet.

The brig was Cerbère, of three 24-pounder and four 6-pounder guns, with a crew of 87 men, 16 of them soldiers, all under the command of lieutenant de vaisseau Menagé. The attack cost the British one man killed (a seaman from Viper), and eight men wounded, including Coghlan and Paddon. The French lost five men killed and 21 wounded, including all their officers; one of the wounded men died shortly thereafter.[25]

The Royal Navy took Cerbère into service under her existing name. Pellew's fleet waived their right to any prize money as a gesture of admiration for the feat.[25] Pellew also recommended Coghlan's promotion to Lieutenant, which followed, though Coghlan had not served the requisite time in grade.[26] Earl St. Vincent personally gave Coghlan a sword worth 100 guineas,[26] in order to "prevent the city, or any body of merchants, from making him a present of the same sort".[27] In 1847 the Admiralty awarded the Naval General Service Medal with clasp, "29 July Boat Service 1800" to the four then surviving claimants from the action.

On 1 November Viper recaptured Diamond.[28]

On 1 February 1801, Viper captured Mont Blanc.[29] Mont Blanc was advertised for sale in April. She was a schooner of 10869⁄94 and had been captured as she was sailing from Cayenne to Lorient. Her cargo was for sale too, including 19 elephants' teeth, as were six brass guns and four iron guns.[30]

Next, Viper and Brilliant captured Petit Felix on the 15th of the month.[29] Petit Felix was a new Chasse-marée of 5310⁄94 tons (bm). Her cargo, for exportation, consisted of brandy, red and white wine, castile soap, tar, twigs, and whisk brooms.[30]

Also on 15 February Viper captured Jupiter.[31]

On 1 April, Viper was in company with Atalante when they encountered four French privateers off Land's End. Three of the privateers escaped. Nevertheless, Atalante pursued one and after a chase of 17 hours captured her. She turned out to be the brig Héros, of Saint Malo. She was armed with 14 guns and had a crew of 73 men under the command of her master, Renne Crosse.[32]

Viper shared in the proceeds of the capture of Adelaide and a brig on 8 August as part of Pellew's squadron.[33] Viper was then paid off in October 1801.

Napoleonic Wars

In September 1803 Lieutenant Robert Jump assumed command of Viper.[3] On 8 May 1806, Viper detained and sent into Plymouth the ship Hercules.[34] In 1806 Lieutenant Daniel Carpenter replaced Jump. Viper, under Carpenter, detained Hetty on 6 August and Diana on 27 August.[35]

Fate

The Commissioners of the Royal Navy put Viper up for sale on 13 October 1809 at Plymouth.[36] She was sold that year.

Notes

- At the time (1780-84), Britain and the Dutch Republic were embroiled in the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War.

- Bouvet later recalled losing two dead and eight wounded.[18]

- A first-class share of the proceeds of the hull, stores, and head money was worth £42 19s 6½d; a fifth-class share, that of a seaman, was worth 1s 9½d.[24]

Citations

- "The Greyhound Excise Cutter. Capt Wm Watson - on a wind, chasing - National Maritime Museum".

- "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 246.

- Winfield (2008), p.353.

- "NMM, vessel ID 378537" (PDF). Warship Histories, vol iv. National Maritime Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "No. 12395". The London Gazette. 7 December 1782. p. 2.

- "No. 12432". The London Gazette. 15 April 1783. p. 5.

- "No. 12396". The London Gazette. 10 December 1782. p. 5.

- "No. 12293". The London Gazette. 4 May 1782. p. 1.

- "No. 12309". The London Gazette. 29 June 1782. p. 2.

- O'Byrne (1849), Vol. 1, p.281.

- North Devon magazine: containing the cave and lundy review, Volumes 1-2, pp.56-62.

- Naval Chronicle, Vol. 1, p.429.

- "No. 15362". The London Gazette. 5 May 1801. p. 504.

- "No. 13945". The London Gazette. 29 October 1796. p. 1029.

- "No. 14023". The London Gazette. 27 June 1795. pp. 614–615.

- Naval Chronicle, Vol. 1, p.441.

- Naval Chronicle, Vol. 2, p.259.

- Fabre (1886), pp.9-12.

- "No. 15218". The London Gazette. 31 December 1799. p. 4.

- "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 239.

- "No. 15267". The London Gazette. 14 June 1800. p. 665.

- "No. 15386". The London Gazette. 14 July 1801. p. 843.

- "No. 15541". The London Gazette. 14 December 1802. p. 1335.

- "No. 15434". The London Gazette. 8 December 1801. p. 1466.

- "No. 15282". The London Gazette. 5 August 1800. pp. 897–898.

- Long (1895), pp. 219–20.

- Littell (1844), Vol. 1, p.237.

- "No. 15526". The London Gazette. 23 October 1802. p. 1126.

- "No. 15422". The London Gazette. 27 October 1801. p. 1307.

- "Advertisements & Notices." Trewman's Exeter Flying Post [Exeter, England] 23 April 1801: n.p.

- "No. 15563". The London Gazette. 1 March 1803. p. 232.

- "No. 15352". The London Gazette. 7 April 1801. p. 382.

- "No. 15481". The London Gazette. 18 May 1802. p. 508.

- "No. 16088". The London Gazette. 17 November 1807. p. 1544.

- "No. 16354". The London Gazette. 10 March 1810. p. 447.

- "No. 16300". The London Gazette. 23 September 1809. p. 1543.

References

- Fabre, Eugène (1886) Voyages et combats, Volume 2. (Berger-Levrault et Cie).

- Littell, Eliakim (1844) The living age. (Littell, Son and Co.).

- Long, William H. (1895). Medals of the British navy and how they were won: with a list of those officers, who for their gallant conduct were granted honorary swords and plate by the Committee of the Patriotic Fund. London: Norie & Wilson.

- O’Byrne, William R. (1849) A naval biographical dictionary: comprising the life and services of every living officer in Her Majesty's navy, from the rank of admiral of the fleet to that of lieutenant, inclusive. (London: J. Murray), vol. 1.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 978-1861762467.

This article includes data released under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported UK: England & Wales Licence, by the National Maritime Museum, as part of the Warship Histories project.