Hemosiderin

Hemosiderin or haemosiderin is an iron-storage complex that is composed of partially digested ferritin and lysosomes. The breakdown of heme gives rise to biliverdin and iron.[1][2] The body then traps the released iron and stores it as hemosiderin in tissues.[3] Hemosiderin is also generated from the abnormal metabolic pathway of ferritin.[3]

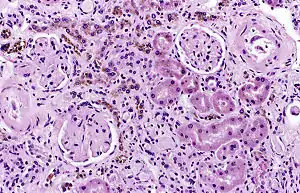

It is only found within cells (as opposed to circulating in blood) and appears to be a complex of ferritin, denatured ferritin and other material.[4][5] The iron within deposits of hemosiderin is very poorly available to supply iron when needed. Hemosiderin can be identified histologically with Perls' Prussian blue stain; iron in hemosiderin turns blue to black when exposed to potassium ferrocyanide.[6] In normal animals, hemosiderin deposits are small and commonly inapparent without special stains. Excessive accumulation of hemosiderin is usually detected within cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) or occasionally within epithelial cells of the liver and kidney.

Several disease processes result in deposition of larger amounts of hemosiderin in tissues; although these deposits often cause no symptoms, they can lead to organ damage.

Hemosiderin is most commonly found in macrophages and is especially abundant in situations following hemorrhage, suggesting that its formation may be related to phagocytosis of red blood cells and hemoglobin. Hemosiderin can accumulate in different organs in various diseases.

Iron is required by many of the chemical reactions (i.e., oxidation-reduction reactions) in the body but is toxic when not properly contained. Thus, many methods of iron storage have developed.

Pathophysiology

Hemosiderin often forms after bleeding (haemorrhage).[7] When blood leaves a ruptured blood vessel, the red blood cell dies, and the hemoglobin of the cell is released into the extracellular space. Phagocytic cells (of the mononuclear phagocyte system) called macrophages engulf (phagocytose) the hemoglobin to degrade it, producing hemosiderin and biliverdin. Excessive systemic accumulations of hemosiderin may occur in macrophages in the liver, lungs, spleen, kidneys, lymph nodes, and bone marrow. These accumulations may be caused by excessive red blood cell destruction (haemolysis), excessive iron uptake/hyperferraemia, or decreased iron utilization (e.g., anaemia of copper toxicity) uptake hypoferraemia (which often leads to iron deficiency anemia).

Cellular iron is found as either ferritin or hemosiderin. It is identified in cells by the Perls or Prussian blue reaction, in which ionic iron reacts with acid ferrocyanide to impart a blue color.<Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology>

Diseases associated with hemosiderin deposition

Hemosiderin may deposit in diseases associated with iron overload.[8] These diseases are typically diseases in which chronic blood loss requires frequent blood transfusions, such as sickle cell anemia and thalassemia.

References

- "Hemosiderin". Definition, Staining, Function and Treatment. 2019-05-04. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- Kalakonda, Aditya; John, Savio (2018-10-27). "Physiology, Bilirubin". NCBI Bookshelf. PMID 29261920. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- Litwack, Gerald (2018). "Micronutrients (Metals and Iodine)". Human Biochemistry. Elsevier. pp. 591–643. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-383864-3.00019-3. ISBN 978-0-12-383864-3. S2CID 90250940.

- Richter, Goetz (1 August 1957). "A Study of Hemosiderosis with Aid of Electron Microscopy". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 106 (2): 203–218. doi:10.1084/jem.106.2.203. PMC 2136742. PMID 13449232.

- Fischbach, FA; Gregory, DW; Harrison, PM; Hoy, TG; Williams, JM (December 1971). "On the structure of hemosiderin and its relationship to ferritin". Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 37 (5): 495–503. doi:10.1016/S0022-5320(71)80020-5. PMID 5136270.

- Kumar, Abbas, Aster, Vinay, Abul K., Jon C. (2015). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 9th Edition. Elsevier. p. 650. ISBN 978-1-4557-2613-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Forensic Pathology".

- "Hereditary haemochromatosis through 150 years". Tidsskrift for den Norske Legeforening. Retrieved 2018-07-14.