Hahoetal

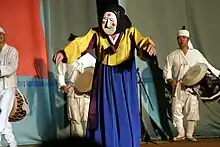

Hahoetal masks (하회탈/河回탈) are the traditional Korean masks worn in the Hahoe Pyolshin-gut t'al nori ceremony dating back to the 12th century.[1] They represent the stock characters needed to perform the roles in the ritual dance dramas included in the ceremony. The masks originated in the Hahoe Folk Village and Byeongsan Village, North Gyeongsang Province, South Korea. They are counted among the treasures of South Korea, and the oldest Hahoe mask is on display in the National Museum of Korea.[2][3] The Hahoetal masks are considered to be among of the most beautiful and well known images representing Korean culture.[4] The South Korean government named the masks "National Treasure #121" and the dance of the Pyolshin-gut Ta'l nori as "important intangible cultural asset #69."[5] The Hahoe Mask Dance Drama Preservation Society performs the dance drama weekly at the Hahoe folk village for tourists, while Andong City hosts an international mask dance festival every October.[6]

| Hahoetal | |

| |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 하회탈 |

| Revised Romanization | Hahoetal |

| McCune–Reischauer | Hahoet'al |

Legend

The exact origin of the Hahoetal masks is not clearly known, although there is a colorful legend about their original construction. It is said that a young man named Hur received instructions in a dream from his local protecting deity to construct the masks. The decree was that he had to create all of the masks in private, completely unseen by any other human being. He closed himself off in his home, hanging straw rope around the house to prevent anyone from entering while he finished his task. A young woman in love with Hur grew impatient after not seeing him for several days. She decided to secretly watch him by making a small hole in his paper window. Once the deities' rules were broken, Hur immediately started vomiting and haemorrhaging blood, dying on the spot. It is said he was working on the final mask of Imae when he died, leaving it unfinished without a chin. The girl then died of guilt and a broken heart. The villagers performed an exorcism allowing for their souls to be raised to the rank of local deity, and they were able to marry in the afterlife. The Hahoe Pyolshin-gut ritual ceremony was developed to honor them and console their tormented souls. [7][8]

Mask construction

Hahoe pyolsin-kut became one of the most popular forms of t'al nori (talchum), which are Korean dance mask dramas. There are over a dozen t'al nori still performed today. T'al nori masks are traditionally made from gourds and paper-mache using Korean mulberry paper called hanji. They are then painted, lacquered and decorated. Most t'al are burned to exorcise any demons inhabiting the masks during and after the performance. The Hahoetal are noticeably different from other Korean masks in that they are carved out of solid pieces of wood. Historically, Hahoetal have been carved from the wood of alder trees. They are painted as needed and lacquer is applied two or three times to color each mask properly. Except for the partial area around the chin, the masks are carved in asymmetry with a view to express a more facial-like expression to boost the satire and fun of the drama, while also representing the typical facial look of the Korean people.[1]

The gaze transforms the shape of the mask owing to its asymmetric structure from left to right and from top to bottom. The angle of the mask when presented to the audience seems to offer a variety of expressions, and some of the masks have detached jaws connected with string or twine allowing for an even larger range of expression. The seeming change of expression is needed to honor the play's social situations and satire: harmony with lack of harmony, symmetry in asymmetry and perfection in imperfection. The Hahoetal are not burned after performances, but returned to their shrines as they are considered sacred objects. If one wants to view the masks, that person has to offer a ritual to the spirits. The Hahoe pyolsin-gut functions to honor the local deities, and therefore earns the permission to use the masks in the ritual dramas, which then are returned to their shrines to await the next ceremony.[9]

The Twelve Masks of the HAHOETAL

The twelve masks of the Hahoetal represent the characters needed to perform all the roles in the Hahoe pyolsin-gut. Of the twelve original masks, nine remain and are counted among the national treasures of Korea. Each mask has a unique set of design characteristics to portray the full range needed in the representation of these stock characters. They are:[1][7]

Chuji (the winged lions): These masks represent two Buddhist winged lions, which act as protectors from evil during the ritual performance. They are long ovals adorned with feathers and often painted red. They are not worn over the face, but held in the hands of the performers.

Kaksi (the young woman/bride): This mask represents a goddess in the first play of the cycle and a young bride in later episodes. This mask has a closed mouth and closed downward lowered eyes, indicating that she is both shy and quiet. Her eyes are not symmetrical, and the mask is carved and painted to have long black hair. The mask is constructed from one solid piece of wood.

Chung (the Buddhist monk): Monks held a great deal of power and influence, and were therefore susceptible to corruption, greed and mockery from the lower classes. Chung is therefore portrayed as a lecherous and gluttonous character in the plays. The mouth of the mask is a separate piece from the top and attached with cords, allowing for movement to represent laughter. The eyes are narrow, and there is a small horn-like bump on the forehead. The mask is often painted red to represent middle-age.

Yangban (the aristocrat): The character with the most power, and therefore the object of extreme mockery in the plays. The eyes are painted closed, with deep dark eyebrows and wrinkles surrounding them. The chin is a separate piece from the top of the mask, and the actors can lean forward and back to make the mask smile or frown as needed.

Ch'oraengi (the aristocrat's servant): The wise fool, this character mocks and ridicules his master, providing much of the comedy for the plays. He has a crooked mouth with his sharp teeth showing and bulging eyes set in a deep socket with a solid dark eyebrow. The expression of the mask shows stubbornness, anger and a mischievous and meddling nature.

Sonpi (the teacher/scholar): Another character holding high social status, the mask has flared nostrils and sharply defined cheekbones to show an air of disapproval, conceit and disdain. The mask is wider at the top, coming almost to a point at the chin to represent and mock the large brain of the know-it-all scholar. The mask has a separate jaw attached with a chord or string.

Imae (the scholar's servant): This character is portrayed as a jolly fool, with a drooping eyes to express foolishness and naivety. The forehead and cheeks are slanted and there are many wrinkles around the entire face and eyes. It is the only mask without a chin.

Punae/Bune (the concubine): Punae is a forward and sexual character, appearing in the plays as the concubine of either the scholar or the aristocrat. The mask is symmetrical and made of one solid piece of wood. She has a very small mouth with red rouged lips, cheeks and forehead. Her eyes are closed and she has a general look of happiness and good-humor. The mask is constructed with black hair painted on the top of her head and 2 cords/strings hanging from the sides of the mask.

Paekjung (the butcher): The mask has narrow eyes and a separate jaw, allowing the mask to have an evil grin when the actor leaned forward, and appear to be in maniacal laughter when leaning back. The hair and eyebrows are painted black and the mask is covered with wrinkles. The brow is slanted to represent an ill-tempered nature.

Halmi (the old woman): The mask has wide round eyes and an open mouth, both surrounded by wrinkles. The forehead and chin are both pointed to represent a character without the blessings of heaven above or the promise of good fortune later in life. The mask is one solid piece of wood.

Ttoktari (the old man): This mask is lost.

Pyolch'ae (the civil servant/tax collector): This mask is lost.

Ch'ongkak (the bachelor): This mask is lost.

Hahoe pyolsin-gut and T'al nori in performance

Hahoe pyolsin-gut ceremony functioned to honor local deities and perform the rites of exorcism over evil spirits, therefore bringing prosperity to the village. Beyond the original shamanistic functions, the plays offered a chance for the oppressed lower classes to gather and mock the Yangban ruling class. The humor was base and sexually taboo, especially for the ethics of the Yangban, offering a carnivalesque entertainment for the masses. T'al nori generally dealt with three themes from village to village: the hypocrisy and greed of the ruling class, the lecherous behavior or the monks and the servants complaining of the dim-wittiness of their masters.[10]

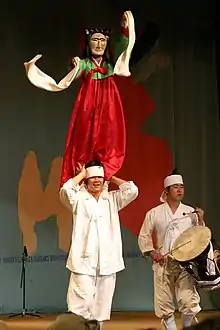

The t'al nori start with a dance followed by a ceremony honoring the hosting deity who protected that village. Once the ceremony is performed, the plays are performed. Dances also ended the celebration, framing the plays which could be performed in any order. Acrobats were often showcased between chapters of the play cycle as well. Most performances of t'al nori included a Yangban episode, an old woman episode and a monk episode, but otherwise varied greatly from village to village. Performances did not need a formal stage, but could be performed anywhere with the space to allow for a band, a changing area for the actors, room for the performance and a place to put the audience. Performances were most often held in village courtyards in front of the altar to the local deity who protected that village, called a songangdae. In larger towns, performances were often staged at the bottom of hills to allow the audience raked viewing, and some of the largest towns built temporary formal stages for the performances.[12]

A small band would accompany performances, providing the varying rhythms and melodies needed to perform the dances within the plays. Percussion is traditionally provided by the janggo, which is a drum in the shape of an hourglass, and various versions of a buk, which is a Korean wooden drum skinned to play at both ends. A kkwaenggwari, or small, hand-held flat gong, is also used throughout the performance. Melody is traditionally provided by the daegum, which is a large bamboo flute and the piri, which is a large double reed oboe also made from bamboo. The haegeum, which is a double-stringed "fiddle" rounds out the band. The rhythms and tempo of the band match the status or actions of the characters as well as providing the base for the formalized dances. For example, slow rhythms and melodies would show and accompany elegance, while fast music would underscore comedic antics or excitement.[13]

The Episodes of the Pyolshin-gut t'al nori

When the Pyolshin-gut t'al nori ceremony is performed in its entirety, it consists of ten "episodes." They are:

Opening rituals/"Piggyback" episode: The ceremony begins with a forty to fifty foot pole being erected to honor the village's guardian deity. The pole has five brightly colored pieces of fabric and a bell on top. A second, smaller pole is built for the "Deity of the Home-site," also with five pieces of fabric on the top. The villagers and audience then prays for the Gods to descend and bless the proceedings, and the bell on top the larger pole rings to signify their approval. The villagers then throw pieces of clothing at the poles, trying to have them drape over them. Success would ensure personal blessings of prosperity. The master of ceremonies and performers then start marching down to the performance site followed by the audience, playing music and dancing along the way. The performer wearing the Kaksi bride mask is carried to the performance, as she is representing the deity of the girl form the legend of the masks, and deities cannot touch the ground. This action earns the deity's blessing for the proceedings.

The Winged Lions Dance: Two performers carry the Chuji masks and dance around the playing space, loudly opening and closing the mouths of the masks. The purpose of this dance is to ensure the safety of the playing space and actors by expelling evil spirits and demonic animals, which would be scared of the winged lions. Once the dance is done, the stage has been purified.

The Butcher Episode: Paekjung, the butcher, dances around and taunts the audience. He kills a bull and then starts trying to sell the heart and other organs to the audience. The audience refuses and he shows frustration at the lack of success in selling off the parts by throwing tantrums and shouting at the audience. He then raises the game by making an energetic attempt to sell the bull's testicles. He runs through the audience trying desperately to finish his task.

The Old Widow Episode: Halmi, the old woman, tells the story of losing her husband the day after their wedding, and expresses her grief at having been a widow since she was fifteen. She sings a song at her loom telling her tale.

The Corrupt Monk Episode: Chung, the Buddhist monk, watches Punae/Bune dance around the stage. She then urinates on the ground, Chung scoops up the wet earth and smells it and is instantly taken over with lust. The two dance a lascivious dance - unknowingly being watched by Sonpi and Yangban. They then run off together to the disapproval of the scholar, aristocrat and their servants.

The Aristocrat and the Scholar Episode: Sonpi, the scholar, and Yangban, the aristocrat, fight over their shared desire for Punae/Bune, the concubine. They argue about their worthiness, citing examples of their education and desire, and then compete to buy the bull testicles from the butcher as a sign of virility to win Punae's affection. The three come to amiable terms and all dance together. Their servants, Ch'oraengi and Imae, mock their actions directly to the audience. Once they overhear the mockery and disdain expressed by the servants who also tell them the tax collector is coming, Yangban, Sonpi and Punae scatter.

The Wedding Episode: Villagers compete to present the couple with their personal mat to be used for their wedding night. It is believed that anyone successfully adding their mat to the pile will be blessed with prosperity. A small wedding ceremony is then performed on a collection of mats piled from the offerings of the audience.

The Wedding Night/Bridal Chamber: Ch'ongkak, the bachelor, ceremoniously removes Kaksi's robe and they lay down together on their pile of wedding mats, acting out the consummation of their marriage. Afterwards, the couple falls asleep and Chung jumps out of a wooden chest and murders Ch'ongkak.This scene is played at midnight, and due to its graphic nature women and children were forbidden to attend.[1][7]

Performance today

The Hahoe pyolsin-kut ceremony stopped being performed in the Hahoe Village in 1928 due to the demands of Japanese rule.[14] Under the leadership of Master Han-sang Ryoo, the Hahoe Mask Dance Drama Preservation Society organized all existing manuscripts for the ceremony, and from 1974-1975 meticulously recreated the ritual performance. They continue to perform the dances domestically and internationally, as well as training and passing on the traditions to younger generations.[15] A six play version is performed most weekends in the Hahoe Village for locals and tourists, and the full length version is performed annually. The Andong Maskdance Festival is held each year in Andong City, North Gyeongsang Province, South Korea, of which Hahoe Village is a part. Starting late September and running over a week, it features performances by many Korean and international mask dance companies, as well as contests, plays, mask making workshops and concerts to name a few of the available attractions. It is part of the Korean Folk Arts festival, which celebrated its 45th anniversary in 2016.[16]

External links

- Hahoe Mask Dance Drama: short article featuring several photos of the ritual in performance

- Hahoe Mask Museum: images and detailed descriptions of each of the Hahoetal

- Hahoetal Preservation Society: website of the group dedicated to preserving the Hahoe pyolsin-kut ceremony

- https://sknsk.wordpress.com/2015/01/20/hahoe-byeolsingut-talnori-a-traditional-masked-drama/: article with link to videos on YouTube

- https://web.archive.org/web/20100113163001/http://www.maskdance.com/: official website for the Andong Maskdance Festival

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1324: Photos and information about Hahoe and Yangdong village

References

- Cho, Oh-kon (1998). Traditional Korean Theater. Berkeley, California: Asian Humanities Press. ISBN 0-89581-876-0.

- Kdata.co.kr

- "Hahoe Mask museum". Archived from the original on 2012-02-09. Retrieved 2013-01-23.

- 한국의 대표 이미지, 하회탈 Inside life. Chosun.com

- Local specialty of Andong Andong city tour

- Hahoe Mask Dance Drama Koreatimes.co.kr-Culture

- Jang, Mikyung (2013). "Analytical Psychological Meaning of Masks in the Hahoe Pyolshin Gut Tal (Mask) Play Dance in Korea". Journal of Symbols & Sandplay Therapy. 4 (1): 16–20. doi:10.12964/jsst.130003.

- Min-jeong, Kim. "Masks Play Many Parts in Korean Culture: Colorful Images Have Been Used for Warding off Evil Spirits and as Costumes in Comedy" – via Korea Times June 07, 1995.

- Saeji, Cedarbough T (2012). "The Bawdy, Brawling, Boisterous World of Korean Mask Dance Dramas". Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review. 1 (2): 439–468. doi:10.1353/ach.2012.0020.

- Lee, Youngkhill (1995). "Talch'um: Searching for the meaning of play". Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance. 66 (8): 28–31. doi:10.1080/07303084.1995.10607136.

- Julie (2008-05-25), Hahoe mask, retrieved 2016-12-16

- "A Study of Performativity in Korean Mask-Dance Theatre". Journal of Korean Theatre Studies Association (42): 5–27.

- Kim, Joo-Yeon (2006). "Talchum: Korean masked dance". knutimes.com.

- Regular Performance for Hahoe Mask Dance, 2012

- Hahoe maskdance drama

- "Andong Maskdance Festival". Archived from the original on 2010-01-13.