Ham, London

Ham is a suburban[2] district in Richmond, south-west London. It has meadows adjoining the River Thames where the Thames Path National Trail also runs. Most of Ham is in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames and, chiefly, within the ward of Ham, Petersham and Richmond Riverside; the rest is in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames. The district has modest convenience shops and amenities, including a petrol station and several pubs, but its commerce is subsidiary to the nearby regional-level economic centre of Kingston upon Thames.

| Ham | |

|---|---|

| |

.jpg.webp) Housing by Ham Parade | |

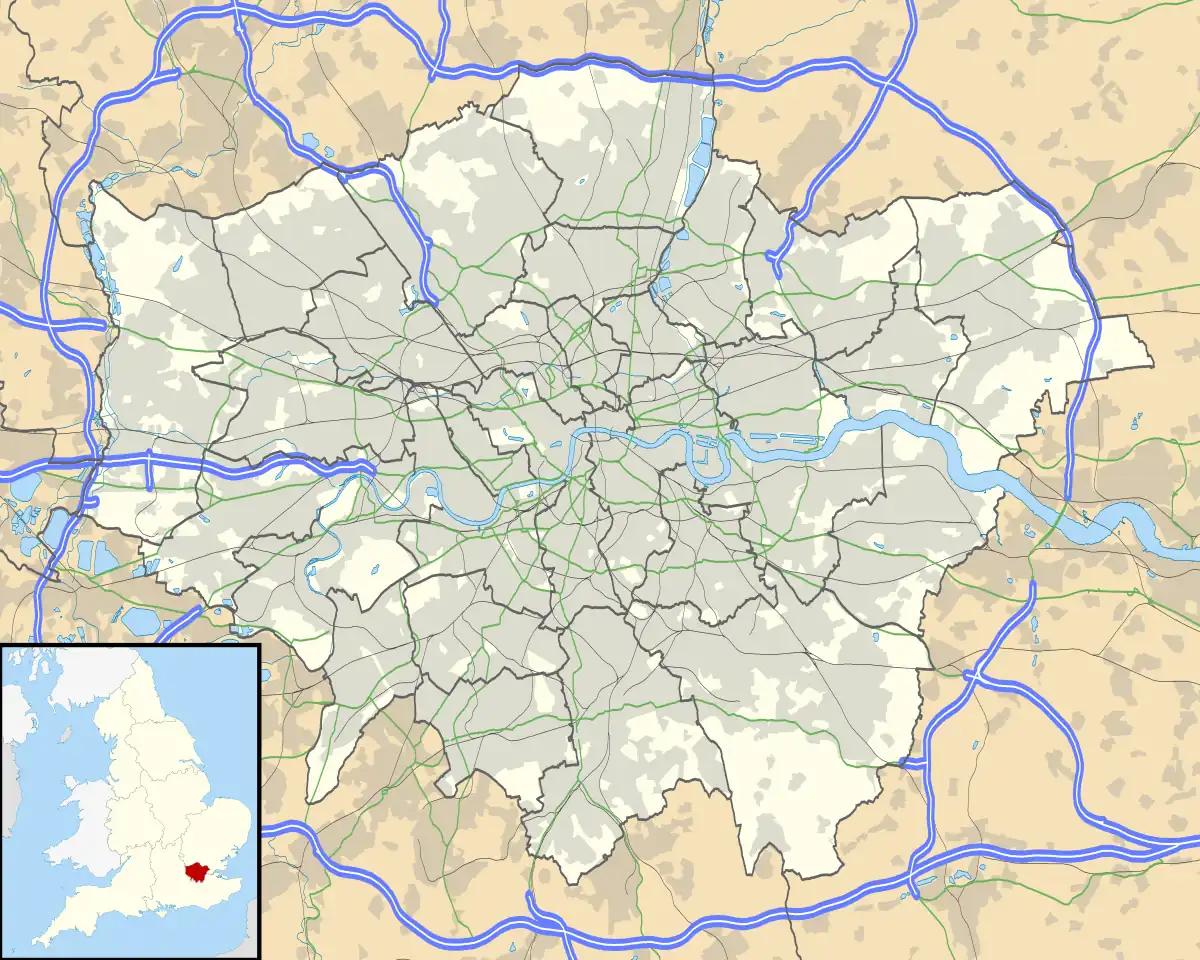

Ham Location within Greater London | |

| Area | 9.26 km2 (3.58 sq mi) |

| Population | 10,317 (Ham Petersham and Richmond Riverside wards 2011)[1] |

| • Density | 1,114/km2 (2,890/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TQ1813673150 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | RICHMOND |

| Postcode district | TW10 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Geography

Ham is centred 9.25 miles (14.89 km) south-west of the centre of London. Together with Petersham, Ham lies east of the bend in the river almost surrounding it on three sides, 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Richmond and 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Kingston upon Thames. Its elevation mostly ranges between 6m and 12m OD but reaches 20m in the foothill side-streets leading to Richmond Park. It has the Thames Path National Trail and is connected to Teddington by a large Lock Footbridge at Teddington Lock. During the summer months a pedestrian ferry, Hammerton's Ferry, links it to Marble Hill House, Twickenham.

The neighbouring land is semi-rural Petersham, Richmond Park, and the town of Kingston. On the opposite side of the river is Teddington and Twickenham (including Strawberry Hill).[3]

Ham is bounded on the west, along the bank of the River Thames, by ancient communal river meadows forming a Local Nature Reserve called Ham Lands.[4] Part of this former pasture land was used for gravel extraction. The last remnant of these gravel pits now forms an artificial lake, connected to the river by a lock. In this area is the Thames Young Mariners 10 acres (0.04 km2) site, operated as a water activity centre by Surrey County Council.[5] The area along the riverside is preserved as a public amenity and nature reserve.

Mostly on low-lying river terrace, Ham today is bounded to the east by Richmond Park, where the land rises at the escarpment of the Richmond and Kingston hills. Small streams that drain this higher ground flow into a watercourse that flows south–north along the foot of the hill, known as Latchmere Stream[6] to the south and Sudbrook to the north. Now subterranean for most of its course, it emerges in Ham Common, near Ham Gate and flows briefly through Richmond Park and exits into Sudbrook Park Golf Course, returning underground before discharging into the Thames at Petersham.[7]

Geology

Ham lies within the London Basin and its London clay bedrock. The low-lying flood plains to the west consist of fluvial gravels, sands and clay. To the east, within Richmond Park, a more erosion-resistant fluvio-glacial deposit of gravels laid down in the interglacial period between 240,000 and 400,000 years ago forms the escarpment ridge that runs north–south between the Richmond and Kingston hills.[8][9]

Toponymy

The name derives from the Old English word Hamme meaning "place in the bend of a river".[10]

Archaeology

The Thames Valley has been inhabited since the Palaeolithic period and finds of Palaeolithic flints near White Lodge, Richmond Park show that Ham was part of early human territory. Later, Mesolithic, flints found at Ham dip, Dann's Pond and Pen Ponds within the park are also evidence of early habitation as are Neolithic barrows on the ridge of the hill overlooking Petersham, Ham and Kingston. These have not been excavated, so it is impossible to date them precisely, but barrows are known to span the period from 3500BC to 900BC.[11] Several surface finds of flint tools, axes, adzes, scrapers, awls chisels and knives as well as arrowheads, hammer stones and flint shards were made during gravel workings in Ham Fields at Coldharbour, near the present day Thames Young Mariners site (51.438655°N 0.325586°W) and further east in maize fields now covered by housing.[9] These finds are made from high quality flint from the North Downs rather than local river-borne flints from the Thames Valley, implying human transportation and a settled rather than nomadic lifestyle in the area. Many of these artifacts are part of the Edwards Collection and housed in the Museum of Richmond. Other finds from Ham are held at the Museum of London including an early Bronze Age collared urn, also from the Edwards Collection.[12][13]

A few finds of Romano-British pottery from the late Iron Age, mid 1st and early 2nd centuries AD show that the area remained inhabited to some extent, though the closest indications of modest Roman settlements are further south in the Canbury area of North Kingston.[12]

The first early Saxon settlement found in the Greater London area was a pit-house, or Grubenhaus, excavated at Ham in the early 1950s. Along with pottery finds dated to the 5th century AD, this suggests the area was amongst the first colonised by Saxon settlers.[12][14]

History

Ham does not appear in Domesday Book of 1086, the nearest entries being Petersham to the north and Coombe to the south-east, all, including the area of Ham, within the hundred of the town of Kingston to the south.[15]

Historically, Ham covered a larger area. The boundaries shown in the tithe map of 1843 are believed to have changed little, if at all, for centuries. The southern boundary between Ham and Kingston spanned the width of the hundred, from near present-day Canbury Gardens on the Thames, about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) eastwards crossing Richmond Park to Beverley Brook. The northern boundary returned through Richmond Park from Beverley Brook, south of White Lodge through the northern Pen Pond, across Sudbrook Park westwards towards Ham Street then veering north back to the Thames.[16]

The earliest known written record of Ham as a separate village dates from the 12th century when Hamma was included in the royal demesne as a member of Kingston, contributing 43s. 4d. in 1168 towards the marriage of Matilda, the eldest daughter of Henry II.[note 1][19]

Between the royal courts at Richmond and Hampton Court, Ham's predominantly agricultural area developed from the beginning of the 17th century, with the construction of Ham House in 1610, the best-preserved survivor of the period. The related history of the Earls of Dysart dominated the development of Ham and Petersham for the following four centuries.

When the park was enclosed by Charles I in 1637, Ham parish lost the use of most of the affected land, over 800 acres (3.2 km2) stretching towards Robin Hood Gate and Kingston Hill, almost half of which was common land. In return for this, a deed was struck which has effectively protected most of the remaining common land, Ham Common, to the present day. The enclosed land, whilst lost to agriculture, remained within Ham's administrative boundaries.

The whole area was referred to as Ham cum Hatch, or Ham with Hatch, until late Victorian times.[20] The enclosure of Richmond Park disrupted the former common land link between the settlements near the present Upper Ham Road and an ancient small settlement near the park's Robin Hood Gate and A3, London road. Local historian, Evelyn Pritchard, assumed that the Robin Hood lands settlement was the location of Hatch, but more detailed examination of Petersham, Ham and Canbury manorial land records by John Cloake provides evidence that Hatch was a hamlet centred around the north-east area of Ham Common, whilst Ham itself lay to the west and north-west of the present common, on the Ham Street approach to the Thames.[21]

Between 1838 and 1848, Ham Common was the site of a Utopian spiritual community and free school called Alcott House (or the "Ham Common Concordium"), founded by educational reformer and "sacred socialist" James Pierrepont Greaves and his followers. Hesba Stretton (real name Sarah Smith), the evangelical children's writer, retired to Ivycroft, Ham Common in 1892 and died there in 1912.[22]

There is a memorial bench outside the Sainsbury's store (formerly Barclays Bank) at Ham Parade to commemorate Angela Woolliscroft, who was murdered in 1976 during a bank robbery.

Government

Since 1965 Ham has been mostly in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames.[23] The rest is in London Borough of Kingston upon Thames. The boundaries between these two boroughs have changed slightly since they were first established.

As the system of hundreds and manors declined, Ham from 1786 was administered by a local "vestry", but as Ham lacked a church of its own until 1832 (and a true vestry until it was enlarged in 1890), it met in the New Inn.[24]

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 established a Board of Guardians, comprising 21 elected guardians for Kingston and its surrounding parishes. Ham always had one or two representatives, but sent very few of its poor to the workhouse, mainly assisting them locally in almshouses.[25] Ham Common Local Government District was formed under the Local Government Act 1858 and was governed by a local board of eight members.[26] However, the vestry system continued in practice until the formation of a local government board in 1871.[27] The Local Government Act 1894 reconstituted the area as Ham Urban District, with an elected urban district council of ten members replacing the local board. It consisted of the civil parish of Ham with Hatch, which was renamed "Ham" in 1897.[28]

The urban district was abolished in 1933, when a county review order included it in an enlarged Municipal Borough of Richmond.[29] The main impact on Ham was that the northern area was linked with Petersham to create a Sudbrook ward, whilst the boundary with Kingston was moved further north to more or less its present limit with Ham "losing" the factories and surrounding land and housing. This substantial boundary change makes meaningful demographic analysis very difficult. The ward itself is now Ham, Petersham and Richmond Riverside. This contains the largest proportion of Richmond Park and of all six main wards which adjoin it.[30]

Economy

Agriculture

Ham was an agricultural community for centuries, with meadow and pasture land mostly along the river, and common grazing. The tithe map of 1842 showed a total area of 1,920 acres (780 ha), but when adjusted for the land in Richmond Park, 449 acres (182 ha) were arable, 290 acres (120 ha) meadow or pasture, 216 acres (87 ha) was common land, and only 1 acre (0.40 ha) woodland. The crops were mainly wheat, barley and oats. with some flax, potatoes, turnips and mangel wurzels. Livestock included cows, sheep, pigs, goats, ducks and chickens as well as horses and donkeys – many of which grazed the common land.[31] Ham had three farms at the time, all on land owned by the Earl of Dysart. Unusually, these remained very little enclosed and the open field system survived in use until the late 19th century.[32] Improvement in transport and the growth of London led to a shift from general mixed agriculture to market gardening by the early 20th century.[33] Ultimately, the same growth fuelled demand for housing land, and this factor along with the greater profitability of gravel extraction on land that could not be used for housing, meant that agriculture in Ham had ceased by the mid-1950s.[34]

Gravel

In 1904 William Tollemache, 9th Earl of Dysart leased part of the farmland to the Ham River Grit Company Ltd to extract sand and ballast. A dock was constructed in 1913 and a lock in 1921, parts of which remain as the Thames Young Mariners water activity centre. A narrow-gauge railway linked the site to the main road. During the Second World War the flooded pits were reputed to have been used to store sections of the Mulberry harbour. After the war, most of the pits were filled with bomb-damage rubble from London. The pits operated until 1952, after which some of the land was used for subsequent housing development. Local resistance to further development led to the area being designated Metropolitan Open Land, preserving Ham Riverside Lands as a nature reserve. It has notably unusual vegetation due to the underlying alkaline rubble instead of the more acidic fluvial deposits.[35][36]

Engineering

Towards the end of World War I, Lord Dysart sold some land south of Ham Common to the Ministry of Munitions for the construction of an aircraft factory on land adjoining what was then still called Upper Ham Road. National Aircraft Factory No. 2 was built in 26 weeks during the winter of 1917. The factory was leased to the Sopwith Aviation Company, based a mile to the south in Canbury Park Road, Kingston, and the company were able to increase greatly its production of Snipe, Dolphin and Salamander fighter planes as a result. At the end of the war, demand ceased. Sopwith tried to buy the factory outright but the government refused. Sopwith Aviation went into voluntary liquidation and reformed in 1920 as H. G. Hawker Engineering at their original Kingston base.[37]

The remaining Ham Factory lease was sold to Leyland Motors, which initially used it to recondition ex-War Department lorries for civilian use. It was then used to produce under licence the Trojan Utility Car between 1922 and 1928.[38] During the 1930s, the factory produced Leyland Cub trucks. World War II shifted production to military vehicles, fire engines, other equipment and munitions. After the war the site produced the chassis for Leyland's trolleybus.[39]

In 1948 the site was sold back to Hawker Aircraft Ltd and it became the main base for Kingston's aviation industry. The Hawker Hunter was produced there in large numbers, driven by cold war demand. The profits allowed the site to be redeveloped as Hawker's UK headquarters and the factory gained an imposing frontage by 1958 in a building that closely linked design and production.[37] The Ham factory played an integral part in the development of the Hawker Kestrel and Hawker Harrier planes. Following the nationalisation of the aircraft industry in 1977. British Aerospace continued to build Harriers and missile kits at the site. Following privatisation in 1985, the site's closure was announced in 1991. It was demolished in 1993 and replaced by further housing development.[39]

Paint and varnish

In 1929 the site on the opposite side of the road to the Leyland factory was developed for the Cellon Doping Company, originally producing Cellon aircraft dope, a synthetic varnish used to waterproof aircraft fabric.[40] The company became part of Pinchin Johnson and was acquired by Courtaulds in 1960, continuing under the International Paint group banner from 1968.[41][42] The factory closed in the 1980s and the site was redeveloped as a small industrial estate.

Today

Apart from one plant nursery, local community, retail and small scale offices, Ham today is predominately a commuter residential area dependent on employment outside the immediate area.

Landmarks

The main feature in Ham is Ham Common which has a cricket pitch, a pond and a woodland.

A straight tree-lined path leads from Ham Common to Ham House, the most significant house in Ham. The section of the path from Ham Common to Sandy Lane is called Great South Avenue and the section from Sandy Lane to Ham House is called Melancholy Walk.

Several notable period houses in Ham cluster around the Common including the Cassel Hospital, Langham House and Ormeley Lodge, which is currently owned by Lady Annabel Goldsmith. Victorian buildings include Latchmere House. Beaufort House in Ham Street, dating from 18C, is Grade II listed and was the home of Lady Juliana Penn from 1795 to her death in 1801.[43] In the grounds of Grey Court School is the Georgian, grade II listed Grey Court House, now called Newman House after Cardinal Newman, who lived there as a child in the early 19th century.[44]

In contrast, Langham House Close, to the west of Ham Common, completed in 1958, is an early example of brutalist architecture. Parkleys, the first large-scale residential development by the pioneering SPAN Developments Ltd of Eric Lyons and Geoffrey Townsend, was begun in 1954 and completed in 1956: it lies just to the north of Ham Parade.[45]

There are four churches: Ham Christian Centre, St Andrew's Church, St Thomas Aquinas Church and St Richard's Church.

Transport

Ham is served by three bus routes: the 65, 371 and K5. All link the town with Kingston upon Thames, with the first two serving Richmond.

Sport

The Ham and Petersham Cricket Club was established in 1815 and cricket is still played on Ham Common.

The Ham Polo Club is at the end of a driveway off the Petersham Road. Though the club has been in existence since 1926 it was in 1954 that the old orchard of Ham House was converted into a polo ground for the club.

The Ham and Petersham Lawn Tennis Club has courts on the south avenue to Ham House in conjunction with Grey Court School.[46]

The former meadow land along the Thames near Ham House became the location of a King George's Field in the 1930s. Covering 10 acres (4.0 ha), it provides cricket, football and tennis facilities. Several sports clubs and activities are based on and nearby.[47][48]

The Ham and Petersham Rifle and Pistol Club, dating from 1907 or perhaps earlier, is near Ham House, with both indoor and outdoor ranges and caters for archery, pistol and rifle shooting.[49]

The Kew and Ham Sports Association provides football and baseball facilities on the playing fields between Ham House and Thames Young Mariners.[50]

The Richmond Baseball and Softball Club plays its home games during the summer season at Connare Field and Flood Field in Ham.

The Thames Young Mariners provides sailing, canoeing, open-water swimming and other sport and outdoor activity facilities.[5]

Demography and housing

| Ward | Detached | Semi-detached | Terraced | Flats and apartments | Caravans/temporary/mobile homes/houseboats | Shared between households[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ward) | 461 | 688 | 1,368 | 1,918 | 0 | 15 |

| Ward | Population | Households | % Owned outright | % Owned with a loan | hectares[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ward) | 10,317 | 4,174 | 31 | 29 | 926 |

Notable people

Living people

- Mitch Benn (born 1970), musician, comedian and author, lives in Ham.[51]

- Christian Furr (born 1966), royal portrait painter and artist, lives in Ham.[52]

- Lady Annabel Goldsmith (born 1934) lives in Ormeley Lodge, a Georgian mansion on the edge of Richmond Park where she brought up the three children she had by Sir James Goldsmith: Jemima Khan, writer and campaigner; Zac Goldsmith, Tory life peer and MP for Richmond Park; and Ben Goldsmith, financier and environmentalist.[53][54]

- Stephen Jakobi, crime fiction writer and human rights lawyer who founded Fair Trials Abroad, lives in Ham.[55]

- Tony Lit, managing director of Sunrise Radio, lives in Ham.[56]

Historical figures

- Princess Marie of Orléans was born in Ham in 1865.

- Claude Bowes-Lyon, Lord Glamis and Cecilia Cavendish-Bentinck, lived at Forbes House on Ham Common.[57] Their daughter, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, married the Duke of York in 1923 and became Queen Elizabeth in 1936 when the duke came to the throne as King George VI. Her elder sister, Violet Hyachinth Bowes-Lyon (1882–1893), died of diphtheria at Forbes House and is buried at St Andrew's Church, Ham.

- Nigel Dempster (1941–2007), British journalist, author and broadcaster, lived at Ensleigh Lodge, Ham Common.[58][59]

- George Gale (1929–2003), cartoonist, lived in Ham and on Little Green, Richmond.[60]

- James Goldsmith (1933–1997), billionaire financier, and his family lived at Ormeley Lodge.[53]

- Emily Hornby (1833–1906), mountaineer and travel writer, died at the Manor House in 1906.

- John Minter Morgan (1782–1854), writer and philanthropist, lived on Ham Common in what is now the Cassel Hospital.[61]

- John Henry Newman, later Cardinal Newman (1801–1890), spent some of his early years at Grey Court, Ham Street, Ham. The site is marked by a blue plaque.[62]

- Beverley Nichols (1898–1983), an English writer and playwright, lived at Sudbrook Cottage from 1958 until his death,[63] with the actor and director Cyril Butcher (1909–1987).[64]

- Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811–1878), an English Gothic revival architect, lived at the Manor House in Ham Street.[65][66]

- Hesba Stretton (real name Sarah Smith; 1832–1911), the evangelical children's writer, retired to Ivycroft, Ham Common in 1892 and died there in 1911.[22]

In popular culture

The 2014 television film The Boy in the Dress, based on the novel by David Walliams, was largely filmed in Ham.[67] For example, the local newsagent's shop used in the film is opposite St Richard's Church, Ham, and other scenes were filmed at Grey Court School.[68]

Scenes from the 2016 film Now You See Me 2 were also filmed in Ham.[69]

Notes

- Lysons attributed a grant of land in 931 by Æthelstan to his minister, Wulfgar, as relating to Ham, London.[17] This is now believed to relate to Ham, Wiltshire.[18]

References

- "Key Statistics; Quick Statistics: Population Density". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 11 February 2003. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- A City of Villages: Promoting a sustainable future for London's suburbs (PDF). August 2002. ISBN 1-85261-393-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Grid square map Ordnance survey website

- "Park Details – Ham Lands". London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- "Thames Young Mariners". Surrey County Council. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- Hawkins, Duncan; Green, Christopher (2007). "A product of its environment: revising Roman Kingston" (PDF). London Archaeologist. 11 (8): 199–203.

- Wilkie, Kim; Battaggia, Marco; Batey, Mavis; Lambert, David; Buttery, Henrietta; Pearce, Jenny; Goode, David; Bentley, David (1994). Landscape Character Reach No 8: Ham. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - McDowall 1996, p. 18.

- Cowie, Robert (2001). "Prehistoric Twickenham" (PDF). London Archaeologist. London Archaeologist Association. 9 (9): 245–252. doi:10.5284/1000168.

- Pritchard 2000, p. 2.

- McDowall 1996, pp. 15–21.

- Barber, Sue (15 June 2011). "The Archaeology of Ham" (PDF). Ham & Petersham magazine. pp. 4–5.

- Lacaille, A.D. (1966). "Mesolithic Facies in the Transpontine Fringes" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. Surrey Archaeological Society. 63: 21–29.

- Merrifield, Ralph (1 January 1983). London, City of the Romans. University of California Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-520-04922-2.

- "Kingston Hundred". Open Domesday. 1086. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- Pritchard 1999, p. 3.

- Lysons, Daniel (1792). "Kingston upon Thames". The Environs of London: volume 1: County of Surrey. Institute of Historical Research. pp. 212–256. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "Event: Charter-witnessing, Grant and GiftS416 – Athelstan 18 granting land to Wulfgar 10". Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- Malden, H. E., ed. (1911). "Kingston-upon-Thames: Manors, churches and charities". A History of the County of Surrey. Institute of Historical Research.

- Pritchard 1999, p. 6.

- Cloake, John (2006). "The Robin Hood Lands, the Hamlet of Hatch and the Manor of Kingston Canbury". Richmond History: Journal of Richmond Local History Society (27): 74–76.

- Demers, Patricia. "Smith, Sarah (1832–1911)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36158. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Richmond upon Thames Registration District". UKBMD. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Pritchard 1999, p. 53.

- Pritchard 2000, p. 11.

- Kelly's Directory of Kent, Surrey & Sussex. Historical Directories. 1891. p. 1327. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- Pritchard 2000, p. 10.

- Kelly's Directory of Surrey. Historical Directories. 1913. p. 234. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- Youngs, Frederic A Jr (1979). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England. Vol. I: Southern England. London. ISBN 978-0-86193-127-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pritchard 2000, p. 25.

- Pritchard 1999, p. 8.

- Pritchard 1999, pp. 10–18.

- Pritchard 2000, p. 19.

- Pritchard 2000, p. 26.

- Green & Greenwood 1980, p. 17.

- "The Ham River Grit Company & The Ham Lands". The Arcadian Times. 7 May 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Sopwith and Hawker at the Ham Factory, North Kingston" (PDF). Kingston Aviation Centenary Project. 9 July 2012.

- "Early history". Trojan Owners' Club. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Adlam, James (5 December 2003). "Ham's past as a centre of industry". Surrey Comet.

- "Aviation Industry Suppliers in Kingston" (PDF). Kingston Aviation Centenary Project. 9 July 2012.

- "Cellon". Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Pinchin, Johnson and Co". Grace's Guide. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- "BEAUFORT HOUSE". Historic England.

- "NEWMAN HOUSE". Historic England.

- "Character Appraisal & Management Plan Conservation Areas – Petersham no.6, Ham Common no.7, Ham House no.23 & Parkleys Estate no.67" (PDF). London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. July 2008. p. 23. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- "Ham and Petersham LTC is a friendly tennis club". Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- "Park details – King Georges Field – London Borough of Richmond upon Thames". London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- "Area analysis Ham and Petersham" (PDF). London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2012.

- "WELCOME to Ham & Petersham Rifle & Pistol Club!". Ham and Petersham Rifle and Pistol Club. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Kew and Ham Sports Association – Home". Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Ham comic raises money for charity" (PDF). Ham and Petersham Magazine: 4. Spring 2013.

- "Bus shelter revolution!" (PDF). Ham and Petersham Magazine. Summer 2011. p. 7. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- Berens, Jessica (13 April 2003). "Young, gifted and Zac". The Observer. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Berridge, Vanessa (2007). "Portrait of a Lady". The Lady. London. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- "MP backs Ham based human rights charity". News Shopper. 28 May 2002. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- Frot, Mathilde (28 December 2018). "All the south west Londoners awarded an MBE this year". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- White, Geoffrey & Cokayne, G. E. (1953). The Complete Peerage. Vol. 12. London: St Catherine's Press. pp. 402–403.

- "I have left my Ham home, Nigel Dempster reveals after divorce hearing". Richmond and Twickenham Times. 5 November 2002.

- "Daily Mail's Nigel Dempster, doyen of newspaper diarists, dies aged 65". Evening Standard. 12 July 2007.

- "Cartoonist who was 'a very nice guy'". Richmond and Twickenham Times. 26 September 2003. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- Boase, George Clement (1894). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 39. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 22–23.

- "Blue Plaques in Richmond upon Thames". Visit Richmond. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Fison, Vanessa (2009). The Matchless Vale: the story of Ham and Petersham and their people. Ham and Petersham Association. pp. 53, 54, 112–117. ISBN 978-0-9563244-0-5.

- "Beverley Nichols' will". The Observer. 22 January 1984. p. 5. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- "The Manor House, Ham (1864–9, 1872–5)". Gilbert Scott org. 5 April 2018.

- Historic England (23 March 2000). "Tomb of Albert Henry Scott in the Churchyard of St Peter's Church (1380183)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- "Film Richmond Newsletter" (PDF). London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. 2015.

- "The Boy in the Dress (2014 TV Movie) Filming & Production". IMDb.

- "Now You See Me 2 (2016) Filming & Production". IMDb.

Sources

- Fison, Vanessa (2009). The Matchless Vale: the story of Ham and Petersham and their people. Ham and Petersham Association. ISBN 978-0-9563244-0-5.

- Green, James; Greenwood, Silvia (1980). Ham and Petersham as it was. Richmond Society History Section. ISBN 0-86067-057-0.

- McDowall, David (1996). Richmond Park: The Walker's Historical Guide. David McDowall. ISBN 0-9527847-0-X. OCLC 36123245. OL 8477606M.

- Pritchard, Evelyn (1999). A Portrait of Ham in Early Victorian times 1840–1860 (2nd ed.). Alma Books. ISBN 978-0-9517497-5-3.

- Pritchard, Evelyn (2000). "The historical background". In Chave, Leonard (ed.). Ham and Petersham at 2000. Ham Amenities Group. pp. 2–28. ISBN 0-9522099-4-2.