Han Feizi

The Han Feizi (simplified Chinese: 韩非子; traditional Chinese: 韓非子; pinyin: Hánfēizi; lit. 'Writings of Master Han Fei') is an ancient Chinese text attributed to the Legalist political philosopher Han Fei.[1] It comprises a selection of essays in the Legalist tradition, elucidating theories of state power, and synthesizing the methodologies of his predecessors.[2] Its 55 chapters, most of which date to the Warring States period mid-3rd century BCE, are the only such text to survive fully intact.[3][2] The Han Feizi is believed to contain the first commentaries on the Dao De Jing.[4][5] Temporarily coming to overt power as an ideology with the ascension of the Qin dynasty,[6]: 82 the First Emperor of Qin and succeeding emperors often followed the template set by Han Fei.[7]

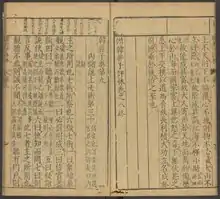

A late 19th century edition of the Hanfeizi by Hongwen Book Company | |

| Author | Han Fei |

|---|---|

| Original title | 韩非子 |

| Country | China |

| Language | Chinese |

| Genre | Chinese classics |

Publication date | 3rd century BCE |

| Han Feizi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 韓非子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 韩非子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "[The Writings of] Master Han Fei" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

Often considered the "culminating" or "greatest" Legalist texts, Han Fei was dubbed by A. C. Graham amongst as the "great synthesizer" of 'Legalism'".[8][9] Sun Tzu's The Art of War incorporates both a Daoist philosophy of inaction and impartiality, and a 'Legalist' system of punishment and rewards, recalling Han Fei's use of the concepts of power and technique.[10]

Among the most important philosophical classics in ancient China,[11] it touches on administration, diplomacy, war and economics,[12] and is also valuable for its abundance of anecdotes about pre-Qin China. Though differing considerably in style, the coherency of the essays lend themselves to the possibility that much was written by Han Fei himself, and are generally considered more philosophically engaging than the Book of Lord Shang.[13] Zhuge Liang is said to have attached great importance to the Han Feizi, as well as to Han Fei's predecessor Shen Buhai.[14]

Introduction

Han Fei describes an interest-driven human nature together with the political methodologies to work with it in the interest of the state and Sovereign, namely, engaging in passive observation, and the systematic use of fa (法; fǎ; 'law', 'measurement') to maintain leadership and manage human resources, its use to increase welfare, and its relation with justice.

Rather than rely too much on worthies, who might not be trustworthy, Han Fei binds their programs (to which he makes no judgement, apart from observances of the facts) to systematic reward and penalty (the 'two handles'), fishing the subjects of the state by feeding them with interests. That being done, the ruler minimizes his own input. Like Shang Yang and other fa philosophers, he admonishes the ruler not to abandon fa for any other means, considering it a more practical means for the administration of both a large territory and personnel near at hand.

Han's philosophy proceeds from the regicide of his era. Goldin writes: "Most of what appears in the Han Feizi deals with the ruler's relations with his ministers, [who] were regarded as the party most likely, in practice, to cause him harm." Han Fei quotes the Springs and Autumns of Tao Zuo: "'Less than half of all rulers die of illness.' If the ruler of men is unaware of this, disorders will be manifold and unrestrained. Thus it is said: If those who benefit from a lord's death are many, the ruler will be imperiled."[15][16]

Elements of Han Fei's philosophy

As suitable to a basic introduction, Sinologist Chris Fraser in the Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy elaborates a modern interpretation of the elements of the fajia (or 'Legalists') as attributable to Han Fei. Following figures like Arthur Waley, the three elements essentially represented the view of the subject as introduced by Feng Youlan (1948) until the work of Sinologist Herrlee G. Creel (1970).

Fraser defines Han Fei's Fa as clear, explicit, specific, publicly promulgated standards of conduct encompassing laws, satisfactory job performance, military and bureaucratic promotion, and regulation of the general population. Han Fei aims to replace inherited moral teachings and sage kings with Fa and its officials. Fa prevent deception of the ruler, their transparency prevents official corruption or abuse, and their exactness and public knowledge prevent bending or violation, controlling the population and limiting official power. Fa eliminates differences in treatment between the population and the bureaucracy or aristocracy.

Fraser defines Han Fei's shu as managerial arts or techniques constituting undisclosed and un-codified methods. They include merit-based appointment, strict accountability in relation to job titles, and the employment of reward and punishment ensuring the performance of duties. Officials are assigned duties according to their administrative proposals, whose doctrine under Han Fei is called Xing-Ming. As essentially a private variety of fa, shu is in part an inheritance of the Mohists who advocated meritocracy, and the doctrine of the rectification of names, which is shared with the Confucians and others.

Fraser elaborates shi as connoting institutional power or advantageous position, wielded to implement the standards of conduct and administrative techniques. Based on the idea of the average ruler, it contrasts with the Confucian ideal of rule by moral worth and moral authority, which Han Fei sees as "foolishly unrealistic", condemning the state to constant misgovernment awaiting a sage king. It is secondly based on the idea of ruling and controlling a large number of people, which power and position can accomplish, but charisma cannot. Shi renders moral worth redundant. From a position of power, the ruler employs Fa, wields the handles of life and death, and uses techniques to manage the administration.[17]

Wu wei

Devoting the entirety of Chapter 14, "How to Love the Ministers", to "persuading the ruler to be ruthless to his ministers", Han Fei's enlightened ruler strikes terror into his ministers by doing nothing (wu wei). The qualities of a ruler, his "mental power, moral excellence and physical prowess" are irrelevant. He discards his private reason and morality, and shows no personal feelings. What is important is his method of government. Fa require no perfection on the part of the ruler.[18]

If the Han Fei's use of wu wei was derivative of a proto-Daoism, its Dao nonetheless emphasizes autocracy ("Tao does not identify with anything but itself, the ruler does not identify with the ministers"). Accepting that Han Fei applies wu wei specifically to statecraft, professor Xing Lu argues that Han Fei still considered wu wei a virtue. As Han Fei says, "by virtue [de] of resting empty and reposed, he waits for the course of nature to enforce itself."[19][20]

Tao is the beginning of the myriad things, the standard of right and wrong. That being so, the intelligent ruler, by holding to the beginning, knows the source of everything, and, by keeping to the standard, knows the origin of good and evil. Therefore, by virtue of resting empty and reposed, he waits for the course of nature to enforce itself so that all names will be defined of themselves and all affairs will be settled of themselves. Empty, he knows the essence of fullness: reposed, he becomes the corrector of motion. Who utters a word creates himself a name; who has an affair creates himself a form. Compare forms and names and see if they are identical. Then the ruler will find nothing to worry about as everything is reduced to its reality.

Tao exists in invisibility; its function, in unintelligibility. Be empty and reposed and have nothing to do-Then from the dark see defects in the light. See but never be seen. Hear but never be heard. Know but never be known. If you hear any word uttered, do not change it nor move it but compare it with the deed and see if word and deed coincide with each other. Place every official with a censor. Do not let them speak to each other. Then everything will be exerted to the utmost. Cover tracks and conceal sources. Then the ministers cannot trace origins. Leave your wisdom and cease your ability. Then your subordinates cannot guess at your limitations.

The bright ruler is undifferentiated and quiescent in waiting, causing names (roles) to define themselves and affairs to fix themselves. If he is undifferentiated then he can understand when actuality is pure, and if he is quiescent then he can understand when movement is correct.[21]

The Han Feizi's commentary on the Daodejing asserts that perspective-less knowledge – an absolute point of view – is possible. But scholarship has not generally believed that Han Fei wrote it, given differences with the rest of the text.[22]

Performance and title (Xing-Ming)

Han Fei was notoriously focused on what he termed xing-ming,[23] which Sima Qian and Liu Xiang define as "holding actual outcome accountable to ming (speech)."[13][24][25] In line with both the Confucian and Mohist rectification of names,[26] it is relatable to the Confucian tradition in which a promise or undertaking, especially in relation to a government aim, entails punishment or reward,[26] though the tight, centralized control emphasized by both his and his predecessor Shen Buhai's philosophy conflicts with the Confucian idea of the autonomous minister.[27]

Possibly referring to the drafting and imposition of laws and standardized legal terms, xing-ming may originally have meant "punishments and names", but with the emphasis on the latter.[28] It functions through binding declarations (ming), like a legal contract. Verbally committing oneself, a candidate is allotted a job, indebting him to the ruler.[25][29] "Naming" people to (objectively determined) positions, it rewards or punishes according to the proposed job description and whether the results fit the task entrusted by their word, which a real minister fulfils.[30][26]

Han Fei insists on the perfect congruence between words and deeds. Fitting the name is more important than results.[30] The completion, achievement, or result of a job is its assumption of a fixed form (xing), which can then be used as a standard against the original claim (ming).[31] A large claim but a small achievement is inappropriate to the original verbal undertaking, while a larger achievement takes credit by overstepping the bounds of office.[25]

Han Fei's 'brilliant ruler' "orders names to name themselves and affairs to settle themselves."[25]

"If the ruler wishes to bring an end to treachery then he examines into the congruence of the congruence of hsing (form/standard) and claim. This means to ascertain if words differ from the job. A minister sets forth his words and on the basis of his words the ruler assigns him a job. Then the ruler holds the minister accountable for the achievement which is based solely on his job. If the achievement fits his job, and the job fits his words, then he is rewarded. If the achievement does not fit his jobs and the job does not fit his words, then he will be punished.[25][32][33][34]

Assessing the accountability of his words to his deeds,[25] the ruler attempts to "determine rewards and punishments in accordance with a subject's true merit" (using Fa).[35][25][36][37][38] It is said that using names (ming) to demand realities (shi) exalts superiors and curbs inferiors,[39] provides a check on the discharge of duties, and naturally results in emphasizing the high position of superiors, compelling subordinates to act in the manner of the latter.[40]

Han Fei considers xing-ming an essential element of autocracy, saying that "In the way of assuming Oneness names are of first importance. When names are put in order, things become settled down; when they go awry, things become unfixed."[25] He emphasizes that through this system, earlier developed by Shen Buhai, uniformity of language could be developed,[41] functions could be strictly defined to prevent conflict and corruption, and objective rules (fa) impervious to divergent interpretation could be established, judged solely by their effectiveness.[42] By narrowing down the options to exactly one, discussions on the "right way of government" could be eliminated. Whatever the situation (shi) brings is the correct Dao.[43]

Though recommending use of Shen Buhai's techniques, Han Fei's xing-ming is both considerably narrower and more specific. The functional dichotomy implied in Han Fei's mechanistic accountability is not readily implied in Shen's, and might be said to be more in line with the later thought of the Han dynasty linguist Xu Gan than that of either Shen Buhai or his supposed teacher Xun Kuang.[44]

The "Two Handles"

Though not entirely accurately, most Han works identify Shang Yang with penal law.[45] Its discussion of bureaucratic control is simplistic, chiefly advocating punishment and reward. Shang Yang was largely unconcerned with the organization of the bureaucracy apart from this.[46] The use of these "two handles" (punishment and reward) nonetheless forms a primary premise of Han Fei's administrative theory.[47] However, he includes it under his theory of shu (administrative techniques) in connection with xing-ming.[26]

As a matter of illustration, if the "keeper of the hat" lays a robe on the sleeping Emperor, he has to be put to death for overstepping his office, while the "keeper of the robe" has to be put to death for failing to do his duty.[48] The philosophy of the "Two Handles" likens the ruler to the tiger or leopard, which "overpowers other animals by its sharp teeth and claws" (rewards and punishments). Without them he is like any other man; his existence depends upon them. To "avoid any possibility of usurpation by his ministers", power and the "handles of the law" must "not be shared or divided", concentrating them in the ruler exclusively.

In practice, this means that the ruler must be isolated from his ministers. The elevation of ministers endangers the ruler, from whom he must be kept strictly apart. Punishment confirms his sovereignty; law eliminates anyone who oversteps his boundary, regardless of intention. Law "aims at abolishing the selfish element in man and the maintenance of public order", making the people responsible for their actions.[18]

Han Fei's rare appeal, among Legalists, to the use of scholars (law and method specialists) makes him comparable to the Confucians, in that sense. The ruler cannot inspect all officials himself, and must rely on the decentralized (but faithful) application of fa. Contrary to Shen Buhai and his own rhetoric, Han Fei insists that loyal ministers (like Guan Zhong, Shang Yang, and Wu Qi) exist, and upon their elevation with maximum authority. Though Fa-Jia sought to enhance the power of the ruler, this scheme effectively neutralizes him, reducing his role to the maintenance of the system of reward and punishments, determined according to impartial methods and enacted by specialists expected to protect him through their usage thereof.[49][50] Combining Shen Buhai's methods with Shang Yang's insurance mechanisms, Han Fei's ruler simply employs anyone offering their services.[51]

Comparisons and views

Apart from the influence of Confucianist Xun Zi, who was his and Li Si's teacher, because of the Han Feizis commentary on the Daodejing, interpreted as a political text, the Han Feizi has sometimes been included as part of the syncretist Huang-Lao tradition, seeing the Tao as a natural law that everyone and everything was forced to follow, like a force of nature.

Being older than more recent scholarship, translator W. K. Liao (1960) described the world view of the Han Feizi as "purely Taoistic", advocating a "doctrine of inaction" nonetheless followed by an "insistence on the active application of the two handles to government", this being the "difference between Han Fei Tzŭ's ideas and the teachings of the orthodox Taoists (who advocated non-action from start to finish)." Liao compares Han Fei's thought to Shang Yang, "directing his main attention... to the issues between ruler and minister... teaching the ruler how to maintain supremacy and why to weaken the minister."[52]

Phan Ngọc in his foreword to the Han Feizi praised Han Fei as a knowledgeable man with sharp, logical and firm arguments, supported by large amount of practical and realistic evidence. Han Fei's strict methods were appropriate in a context of social decadence. Phan Ngọc claimed that Han Fei's writings has three drawbacks, however: first, his idea of Legalism was unsuited to autocracy because a ruling dynasty will sooner or later deteriorate. Second, due to the inherent limitation of autocratic monarchy system, Han Fei did not manage to provide the solutions for all the issues that he pointed out. Third, Han Fei was wrong to think that human is inherently evil and only seeks fame and profit: there are humans who sacrificed their own profit for the greater good, including Han Fei himself.[53] Trần Ngọc Vương considered the Han Feizi to be superior to Machiavelli's Prince, and claimed that Han Fei's ideology was highly refined for its era.[54]

Although considering the Han Feizi rich and erudite, Chad Hansen views it as "more polemical than reasoned", and with unjustified assumptions. Hansen does not consider Han Fei particularly original, philosophical or ethical, being almost purely practical, with cynicism recognizable "from all self-described realists" that "rests on the familiar sneering tone of superior realistic insight."[55]: 346

Translations

- Liao, W. K. (1939). The Complete Works of Han Fei Tzu. London: Arthur Probsthain.

- ——— (1959). The Complete Works of Han Fei Tzu, Volume II. London: Arthur Probsthain.

- Watson, Burton (1964). Han Fei Tzu: Basic Writings. New York: Columbia University Press.

See also

References

Footnotes

- Encyclopedia of World Biography

- Lévi (1993), p. 115.

- Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.),

- (Goldin 2013)

- Pines, Yuri (2014), Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri (eds.), "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2023-08-29

- Lu, Xing (1998). Rhetoric in Ancient China, Fifth to Third Century, B.C.E.: A Comparison with Classical Greek Rhetoric. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-216-5.

- Bishop, Donald H. (September 27, 1995). Chinese Thought: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120811393.

- Kenneth Winston p. 315. Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2005] 313–347. The Internal Morality of Chinese Legalism. http://law.nus.edu.sg/sjls/articles/SJLS-2005-313.pdf

- Yu-lan Fung 1948. p. 157. A Short History of Chinese Philosophy. https://books.google.com/books?id=HZU0YKnpTH0C&pg=PA157

- Eno, Robert (2010), Legalism and Huang-Lao Thought (PDF), Indiana University, Early Chinese Thought Course Readings

- Hu Shi 1930: 480–48, also quoted Yuri Pines 2013. Birth of an Empire

- Goldin (2011), p. 15.

- Chen, Chao Chuan and Yueh-Ting Lee 2008 p. 12. Leadership and Management in China

- Pang-White, Ann A. (2016). The Bloomsbury Research Handbook of Chinese Philosophy and Gender. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4725-6986-8.

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- Pines, Yuri (2014-12-10). "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Zhuge Liang ref Paul R. Goldin 2013. Dao Companion to the Han Feizi p.271. https://books.google.com/books?id=l25hjMyCfnEC&dq=%22han+fei%22+%22zhuge+liang%22&pg=PA271 Guo, Baogang (2008). China in Search of a Harmonious Society. p38. https://books.google.com/books?id=UkoStC-S-AMC&pg=PA38 Pines, Yuri (10 December 2014). "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy". Epilogue: Legalism in Chinese History. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/chinese-legalism/ Current Shen Buhai reference is less strong, but Han Feizi is rooted in Shen's administrative doctrine regardless; Shen does not imply Han Fei, but Han Fei implies Shen

- "Home | East Asian Languages and Civilizations". ealc.sas.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- 2018 Henrique Schneider. p.vii. An Introduction to Hanfei's Political Philosophy: The Way of the Ruler.

- Garfield, Jay L.; Edelglass, William (2011-06-09). The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-532899-8.

- Chen, Ellen Marie (December 1975). "The Dialectic of Chih (Reason) and Tao (Nature) in The Han Fei-Tzu". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 3 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6253.1975.tb00378.x.

- Xing Lu 1998. Rhetoric in Ancient China, Fifth to Third Century, B.C.E.. p. 264.

- Roger T. Ames 1983. p. 50. The Art of Rulership.

- http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/saxon/servlet/SaxonServlet?source=xwomen/texts/hanfei.xml&style=xwomen/xsl/dynaxml.xsl&chunk.id=d2.5&toc.depth=1&toc.id=0&doc.lang=bilingual

- HanFei, "The Way of the Ruler", Watson, p. 16

- Han Fei-tzu, chapter 5 (Han Fei-tzu chi-chieh 1), p. 18; cf. Burton Watson, Han Fei Tzu: Basic Writings (New York: Columbia U.P., 1964)

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mark (1997). "Chia I's 'Techniques of the Tao' and the Han Confucian Appropriation of Technical Discourse". Asia Major. 10 (1/2): 49–67. JSTOR 41645528.

- Huang Kejian 2016 pp. 186–187. From Destiny to Dao: A Survey of Pre-Qin Philosophy in China. https://books.google.com/books?id=bATIDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA186

- LIM XIAO WEI, GRACE 2005 p.18. LAW AND MORALITY IN THE HAN FEI ZI

- Hansen, Chad (2000). A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought (reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 371. ISBN 9780195134193.

- Creel, 1974. Shen Pu-hai: A Chinese Political Philosopher of the Fourth Century B.C.

- Hansen, Chad (2000-08-17). A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535076-0.

- Creel 1970, What Is Taoism?, 87, 104

- Makeham, John (1990). "The Legalist Concept of Hsing-Ming: An Example of the Contribution of Archaeological Evidence to the Re-Interpretation of Transmitted Texts". Monumenta Serica. 39: 87–114. doi:10.1080/02549948.1990.11731214. JSTOR 40726902.

- A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought.

- Creel 1970, What Is Taoism?, 83

- Lewis, Mark Edward (1999-03-18). Writing and Authority in Early China. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4114-5.

- Makeham, John (1994). Name and Actuality in Early Chinese Thought. SUNY Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-7914-1984-7.

- Graham, A. C. (15 December 2015). Disputers of the Tao. ISBN 9780812699425.

- Makeham, John (1994-07-22). Name and Actuality in Early Chinese Thought. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1984-7.

- Makeham, John (1994). Name and Actuality in Early Chinese Thought. SUNY Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7914-1984-7.

- Hansen, Chad (2000). A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation. Oxford University Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-19-535076-0.

- Graham, A. C. (2015). Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. Open Court. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-8126-9942-5.

- Makeham, John (1994). Name and Actuality in Early Chinese Thought. SUNY Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7914-1984-7.

- Hansen, Chad (2000). A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation. Oxford University Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-19-535076-0.

- Śarmā, Rāma Karaṇa (1993). Researches in Indian and Buddhist Philosophy: Essays in Honour of Professor Alex Wayman. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 978-81-208-0994-9.

- Goldin, Paul R. (March 2011). "Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese 'Legalism'". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 38 (1): 88–104. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6253.2010.01629.x.

- Creel, 1959 p. 202. The Meaning of Hsing-Ming. Studia Serica: Sinological studies dedicated to Bernhard Kalgren

- Creel 1970, What Is Taoism?, 86

- Creel, 1959 p. 206. The Meaning of Hsing-Ming. Studia Serica: Sinological studies dedicated to Bernhard Kalgren

- "Philosophy of Language in Classical China". philosophy.hku.hk. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- Gernet, Jacques; GERNET, JACQUES AUTOR; Gernet, Professor Jacques (1996-05-31). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- Hansen, Chad (2000-08-17). A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535076-0.

- Makeham, John (1994-07-22). Name and Actuality in Early Chinese Thought. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1984-7.

- Creel, What Is Taoism?, 100

- Creel 1970, What Is Taoism?, 100, 102

- Dehsen, Christian von (2013-09-13). Philosophers and Religious Leaders. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-95109-2.

- Tamura, Eileen (1997-01-01). China: Understanding Its Past. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1923-1.

- Yuri Pines, Submerged by Absolute Power, 2003 pp. 77, 83.

- (Chen Qiyou 2000: 2.6.107)

- A History of Chinese Civilization.

- "XWomen CONTENT". www2.iath.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- Vietnamese translation, 2011, Nhà Xuất bản Văn Học

- "PGS – TS Trần Ngọc Vương: Ngụy thiện cũng vừa phải thôi, không thì ai chịu được!". Báo Công an nhân dân điện tử. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- Hansen, Chad (August 17, 2000). A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195350760 – via Google Books.

Works cited

- Knechtges, David R. (2010). "Han Feizi 韓非子". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part One. Leiden: Brill. pp. 313–317. ISBN 978-90-04-19127-3.

- Lévi, Jean (1993). "Han fei tzu 韓非子". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California Berkeley. pp. 115–24. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Nivison, David Shepherd (1999). "The Classical Philosophical Writings". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 745–812. ISBN 0-521-47030-7.

External links

- Full text of Han Feizi in English and Classical Chinese

- Full text of Han Feizi in Classical Chinese

- Han Feizi at PhilPapers

- Han Feizi 《韓非子》 Chinese text with matching English vocabulary