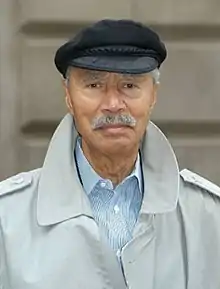

Hans Massaquoi

Hans-Jürgen Massaquoi (January 19, 1926 – January 19, 2013[1]) was a German-American journalist and author. He was born in Hamburg, Germany, to a German mother and a Liberian father of Vai ethnicity, the grandson of Momulu Massaquoi, the consul general of Liberia in Germany at the time.

Hans-Jürgen Massaquoi Sr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 19, 1926 Hamburg, Weimar Republic |

| Died | January 19, 2013 (aged 87) Jacksonville, Florida, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | German, English |

| Citizenship |

|

| Notable work | Destined to Witness |

| Children | 2 |

He wrote his autobiography Destined to Witness. Growing up Black in Nazi Germany, published in 1999. The German translation of it was published the same year, as Neger, Neger, Schornsteinfeger. Meine Kindheit in Deutschland. The title references a racist rhyme that schoolboys taunted him with in 1932. The German version was adapted as a film Destined to Witness and released in 2006.[2] He later published a second autobiography, only in German: Hänschen klein, ging allein … Mein Weg in die Neue Welt (2004).

Childhood in Germany

In his autobiography, Destined to Witness, Massaquoi describes his childhood and youth in Hamburg during the Nazis' rise to power. His autobiography provides a unique point of view: he was one of the very few German-born children of German and African descent. He was often shunned, but escaped Nazi persecution. This duality remained a key theme throughout his early life until he witnessed racism as practiced in colonial Africa and later in the Jim Crow American South.

Massaquoi enjoyed a relatively happy childhood with his mother, Bertha Baetz, who had arrived in Hamburg from Nordhausen and earlier from Ungfrungen. His father, Al-Haj Massaquoi, was a prince of the Vai people who was in Dublin studying law and only occasionally lived with the family at the consul general's home in Hamburg. Eventually, his grandfather Momulu, the first African posted to the diplomatic corps in Europe, was recalled to Liberia. Hans Massaquoi and his mother remained in Germany.

Massaquoi was not aware of any other mixed race children in Hamburg, and like most German children his age he was lured by Nazi propaganda into thinking that joining the Hitler Youth was an exciting adventure of fanfares and games.[3] There was a school contest to see if a class could get a 100% membership of the Deutsches Jungvolk, a subdivision of Hitler Youth, and Massaquoi's teacher devised a chart on the blackboard showing who had joined and who had not. The chart was filled in after each boy joined, until Massaquoi was pointedly the sole student left out. He recalled saying, "But I am German ... my mother says I'm German just like anybody else."[3] His later attempt to join his friends by registering at the nearest Jungvolk office was also met with contempt. The denial of this rite of passage reinforced his perception that he was being ostracized because he was deemed "Non-Aryan" despite his German birth and mostly traditional German upbringing.

After the Nuremberg Laws were passed in 1935, Massaquoi was officially classified as non-Aryan and barred from pursuing a course of education leading to a professional career. Instead he was forced to embark on an apprenticeship as a laborer. A few months before he completed school, Massaquoi was required to go to a government-run job center, where his assigned vocational counselor was Herr von Vett, a member of the SS. Upon seeing the "telltale black SS insignia of dual lightning bolts in the lapel of his civilian suit",[4] Massaquoi expected humiliation. Instead, he was surprised when he was greeted with "a friendly wink", offered a seat and asked to present something he had made. After showing Von Vett an axe and discussing his experience working for a local blacksmith, Massaquoi was informed that he could "be of great service to Germany one day" because there would be a great demand for technically trained Germans to go to Africa to train and develop an African workforce when Germany reclaimed its African colonies.[5] Before Massaquoi left the interview, Von Vett invited him to shake his hand, an unusual move not in keeping with the behavior of other Nazi officials Massaquoi had encountered outside of his neighborhood.[6]

Though he was barred from dating "Aryans", Massaquoi courted a white girl. They had to keep their relationship a secret, especially as her father was a member of the police and the SS. Such relationships were forbidden and classified as Rassenschande (race defilement) under the Nuremberg Laws. They met only in the evenings, when they would go for walks. As he dropped his girlfriend off at her house one night, he was stopped by a member of the SD, the intelligence branch of the SS. He was taken to the police station as he was believed to be "on the prowl for defenseless women or looking for an opportunity to steal".[7] However, he was recognized by a police officer as living in the area and working: "This young man is an apprentice at Lindner A.G., where he works much too hard to have enough energy left to prowl the streets at night looking for trouble. I happen to know that because of the son of one of my colleagues apprentices with him."[7] The SD officer closed the case and gave the Nazi salute, and Massaquoi was allowed to leave the station.[7]

Increasingly as he matured, Massaquoi came to despise Hitler and Nazism. His skin color made him a target for racist abuse, he was often targeted by Nazi employers, he was denied citizenship and subsequently excluded from serving in the armed forces, much to his frustration. This by-fact of the Nuremberg laws, which were expanded in November 1935 to cover Afro-Germans, may however have saved him due from the devastating casualties, especially on the Eastern Front.

During the period following the Allies' near-destruction of Hamburg, he befriended the family of Ralph Giordano, a half-Jewish acquaintance of the surreptitious jazz devotees known as the Swing Kids. The Giordanos, who managed to survive the war in hiding, helped Massaquoi and his mother to secure a nearby basement after their Hamburg neighborhood was destroyed. Giordano, a lifelong friend, became a renowned journalist as well.

Emigration

In 1948 Massaquoi's father, Al-Haj, secured his passage for residency in Liberia. Massaquoi was fascinated and chagrined by Africa. While appreciative that his father made possible his escape from post-World War II Germany, he eventually grew estranged from his father, whom he considered arrogant and somewhat tyrannical. However, the two reconciled just before his father's death which preceded Massaquoi's reconnecting with his maternal family in the United States.

Massaquoi emigrated to the United States in 1950. He served two years in the army as a paratrooper in the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division and fought in the Korean War. He later became a naturalized U.S. citizen. His GI bill helped fund his journalism degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and he worked on his masters at Northwestern University until the impending birth of his first son catapulted into his career at Jet magazine and then Ebony magazine, where he became managing editor. His position allowed him to interview many historical figures of the arts, politics and civil rights movement in America and Africa. He was interviewed in turn by Studs Terkel for his oral history The Good War, and related his unique experiences in Germany under the Nazi government.

Beginning in 1966, Massaquoi visited family and friends in Germany many times, always cognizant of Germany's complex history as the country of his childhood.

Personal life

Massaquoi died on January 19, 2013, his 87th birthday. At the time of his death, Massaquoi was married to Katharine Rousseve Massaquoi. He had two sons by a previous marriage, Steve and Hans Jr., who also survived him.[8]

References

- "Hans Massaquoi, Former Editor Of Ebony Magazine, Who Grew Up Black In Nazi Germany Dies". digtriad.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- Mieder, Wolfgang. 2022. “BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL” Hans-Jürgen Massaquoi’s Proverbial Autobiography Destined to Witness. Proverbium 2022, vol. 39.

- Massaquoi, H J: Destined to Witness, page 80. Fusion Press, 2002

- Massaquoi, H J: Destined to Witness, page 118. Fusion Press, 2002

- Massaquoi, H J: Destined to Witness, page 119. Fusion Press, 2002

- Massaquoi, H J: Destined to Witness, page 118-119. Fusion Press, 2002

- Massaquoi, H J: Destined to Witness, page 136. Fusion Press, 2002

- Hans Massaquoi family

Relevant literature

- Lindhout, Alexandra E. "Hans J. Massaquoi’s "Destined to Witness" as an Autobiographical Act of Identity Formation. Current Objectives of Postgraduate American Studies 7 (2006). open access

- Martin, Elaine. “Hans J. Massaquoi: Destined to Witness: Growing Up Black in Nazi Germany.” Colloquia Germanica, vol. 34, 2001, pp. 91-94.

- Massaquoi, Hans-Jürgen. “A Journey into the Past. Parts I and II.” Ebony (February), 1966, pp. 91-99, and (March), 1966, pp.102-111.

- Massaquoi, Hans-Jürgen.“Hans Massaquoi [autobiographical sketch].” In “The Good War”: An Oral History of World War Two, edited by Studs Terkel, New York: Pantheon Books, 1984, pp. 496-504.

- Mehring, Frank. “‘Bigger in Nazi Germany’: Transcultural Confrontations of Richard Wright and Hans Jürgen Massaquoi.” The Black Scholar vol. 39, 2009, pp. 63-71.

- Mehring, Frank. “Afro-German-American Dissent: Hans J. Massaquoi.” The Democratic Gap: Transcultural Confrontations of German Immigrants and the Promise of American Democracy, edited by Frank Mehring, Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter, 2014, pp. 255-300.

- Nganang, Patrice. “Autobiographies of Blackness in Germany.” Germany’s Colonial Pasts. Eds. Eric Ames, Marcia Klotz, and Lora Wildenthal. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2005, pp. 227-239.

- Walden, Sara. Die Analyse der Sozialisation von Hans-Jürgen Massaquoi an Hand von ausgewählten Aspekten. München: Grin Verlag, 2004.