Hans Unger

Hans Unger (August 26, 1872 – August 13, 1936) was a German painter[1] who was, during his lifetime, a highly respected Art Nouveau artist. His popularity did not survive the change in the cultural climate in Germany after World War I, however, and after his death he was soon forgotten. However, in the 1980s interest in his work revived, and a grand retrospective exhibition in 1997 in the City Museum in Freital, Germany, duly restored his reputation as one of the masters of the Dresden art scene around 1910.[2]

Hans Unger | |

|---|---|

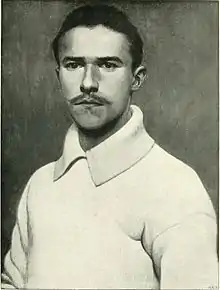

Selbstbildnis im Sweater, around 1899 | |

| Born | Carl Friedrich Johannes Unger August 26, 1872 |

| Died | August 13, 1936 (63 years old) |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | Painting Class in the Royal Dresden Court Theatre Dresden Academy of Fine Arts Académie Julian |

| Known for | Painting Etching Drawing Mosaic Stained glass |

| Notable work | Die Muse Das Welken Mutter und Kind |

| Movement | Art Nouveau Symbolism |

| Awards | bronze medal at Paris World's Fair 1900 title Professor in 1904 bronze medal at St. Louis World's Fair 1904 |

| Patron(s) | Friedrich Preller the Younger Hermann Prell |

Trademark and artistic influences

Unger was a portraitist and a landscape painter but his reputation stems from his paintings, most of them nearly life-size, of "beautiful women dreaming of Arcadia." In fact, it was always the same woman being portrayed: his wife in real life, his muse. Later, his daughter Maja came to share her mother's privileged position. The background to his "Arcadian woman" was quite often a pastoral landscape with high cypresses, a garden or a seaside scene.

In his work he was influenced by some important 19th-century and contemporary artists, among who were: Puvis de Chavannes ("beauty as religion"), Gustave Moreau, Josephin Péladan (the androgyne type), Fernand Khnopff (sphinx-like women, although Unger omitted the lascivious eroticism of Khnopff), William Strang (a British engraver whom Unger met in 1895 in Dresden, and later visited in London) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Other important influences were Edward Burne-Jones, Arnold Böcklin (especially his landscapes) and Max Klinger.[3]

Most important works (and first exhibition)

- Estey Orgeln (poster, 1896)

- Die Muse (The Muse), International Art Exhibition Dresden, 1897

- Das Welken (The Withering), 1902

- Mutter und Kind (Mother and Child), King Albert Museum, Chemnitz, 1912

- Venezianerin (Venetian Woman), Galerie Arnold, Dresden, 1916

Early life

Hans Unger was born into a lower-middle-class family in Bautzen, in the Lausitz in the southeast corner of Germany near Poland and the Czech Republic. His father quickly recognized his son's artistic talent, but since he did not think painting would be a thriving occupation for young Hans, he sent him to trade school. This was not a success and quite soon Unger became a house painter (Anstreicher). In 1887 he took up a training position as a decoration-painter in his hometown. From 1888 to 1893 he was a student in the Painting Class (Malsaal) in the Royal Dresden Court Theatre.

From 1893 to 1895 he studied at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, where his teachers were Friedrich Preller the Younger and Hermann Prell. Unger can be seen as a representative of the Dresdener Jugendstil movement, among whose members were also Sascha Schneider, Selmar Werner and Oskar Zwintscher. In 1894 he spent summer on the island Bornholm where he made a series of watercolors. In 1896 he designed a poster (Plakat) for the Dresden-based organ manufacturing company Estey, which made him internationally famous and launched his career.[4] In all, he published about a dozen posters that feature for the first time his trademark of the beautiful but dreamlike and almost sleepwalking woman, a motif that was so prominent in much Art Nouveau painting.

Early career

In 1897 his painting Die Muse (The Muse) was immediately bought by the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden. From October 1897 to March 1898, he studied at the Académie Julian in Paris where his teachers were Fleury and Lefebvre.[5] Another boost to his career was the commission to design the scenic curtain for the newly built Dresdener Centraltheater, in 1899. Unfortunately, the building was destroyed during the bombing of Dresden by the Allied forces in February 1945.

In 1899 he also took part in the German Art Exhibition (Deutsche Kunstausstellung) in Dresden where he had his own room, decorated with lilac walls and a black wooden rim. Among the works displayed was a Selbstbildnis im Sweater (Self Portrait in Sweater), and Abschied (Farewell), a landscape.

In 1902 he became a member of the newly established German Artists' Union (Deutsche Künstlerbund) and travelled to the North Sea, the Baltic, Italy and Egypt, where he made many watercolors and pastel paintings. Unger was a passionate traveler to the South all his life and the powerful colors in his work reflect this. A testimony to this trait is found in the book Reisebilder aus dem Süden mentioned in the bibliography.

In 1905 Unger designed a mosaic for the tower of the Ernemann Reisekamera factory in Dresden, portraying a Lichtgöttin (Light Goddess). The tower still exists on the Schandauerstrasse. In 1898 and 1910, Unger designed the cover illustration for issues of the magazine Jugend. He also illustrated issues of the magazine Pan.[6]

The apex

Around 1910, Unger's style changed notably. His strokes become bolder; his colors lose their intensity, and his choice of motif becomes increasingly monotonous. The dreamlike female figure that around the turn of the century was captivating and fresh became a cliché. Her face had turned harsh and without expression. However, in his portraits and landscapes Unger remained as powerful as he had ever been.

In 1912, the newly built City Museum in his hometown Bautzen opened and celebrated Unger by giving him his own room. He was at the apex of his fame and was called Dresden's letzter Malerfürst ("The Last Painting Prince of Dresden") by the press.

The outbreak of World War I in November 1914 forced many young artists to join the military and fight at the front, but Unger was already so prominent in his profession that he was spared this fate and could continue to devote himself to his art.

In 1917 Unger participated in the exhibition of the Dresdner Kunstgenossenschaft (Dresden Artists Society). He designed the catalogue's cover image and featured six paintings, among them Salome and Liegende Mädchen (Girls Lying), and six drawings. In 1918 the Dresdner Kunst Ausstellung (Dresden Art Exhibition) featured Unger with another 11 paintings and 10 drawings. attesting to his popularity and renown in the artistic community. His poster for the concerts of his friend, the composer and director Jean-Louis Nicodé, won him a prize in England for "best German poster".

A lost world

In 1918, Germany lost the war, and it also lost the monarchy. The young artists, returning from the front, were disillusioned and wanted only one thing, which was Change, moving even further away from impressionism and copying reality as they had done in the years prior to World War I. Unger's world of idealized women in soothing landscapes had been overhauled by the Zeitgeist and his work was relegated to the background. Nonetheless, he was still one of the wealthiest artists in Dresden, and he continued to travel to Italy, Dalmatia, Spain, Portugal and Africa. Unger's visits to Egypt resulted in an exhibition in the Galerie Baumbach in Dresden in 1927 and in King Fuad I of Egypt becoming one of his patrons.

In 1933 the Sächsischer Kunstverein (Art Association of Saxony) organized an exhibition on the occasion of his 60th birthday. The arts journalist Felix Zimmermann wrote an honorary article on Unger in the Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten of August 25, 1932.

Meanwhile, his health deteriorated. What later turned out to be a kidney disease was treated too late and Hans Unger died in his home in Loschwitz, a suburb of Dresden, on 9 August 1936. He was buried in Loschwitz Cemetery, where his grave still exists. History had certainly caught up with him. Adolf Hitler was already in power for more than three years, the economy was in the worst state of the entire 20th century and the days of Art Nouveau and fin de siècle were certainly over.

Renewed interest

However, the resurging interest in Jugendstil art in the 1960s brought Unger's work back to the attention of the art connoisseurs. In 1987, the City Museum in Bautzen organized an exhibition to commemorate the 125th anniversary of his birth. In 1997 a retrospective exhibition on Unger was held in the City Museum in Freital, Germany. In 2013, an exhibition in Bielefeld titled Beauty and Mystery. German symbolism featured some of his works along with artists that influenced him such as Franz von Stuck, Max Klinger and Arnold Böcklin.[7]

Personal life

Unger married his wife Marie Antonia in 1899. She was to become his muse, his model and the main subject of his works. She is said to have been quite beautiful and the centre of attention of the many friends in the artistic circles in Dresden, especially musicians and writers, which Unger invited to his house.

In 1902, Unger designed his own villa in Loschwitz. His prominence as a daring young artist and his popularity among the Dresden upper class as a portraitist had made him a wealthy man. Unger also designed the entire interior decoration himself. This however was removed during a renovation in the early 1970s. The villa, on the Kügelgenstrasse no. 6, still exists and offers a view on the river Elbe and, further away, on the Dresden city centre.

In 1903, his only child, his daughter Maja, was born, who had clearly inherited her mother's looks. Her godfather was Sascha Schneider, a lifelong friend of Unger. After her death in 1973, Unger's estate was sold and scattered.

Gallery

Die Muse (The muse) (1897)

Die Muse (The muse) (1897) Sonne (Sun)

Sonne (Sun) Weiblicher Akt mit Papagei (Female nude with parrot)

Weiblicher Akt mit Papagei (Female nude with parrot) Liegendes Mädchen (Reverie) (1917)

Liegendes Mädchen (Reverie) (1917) Plakat für Estey Orgeln (Poster for the Estey organ factory) (1896)

Plakat für Estey Orgeln (Poster for the Estey organ factory) (1896) Mutter und Kind (Mother and child) (around 1909)

Mutter und Kind (Mother and child) (around 1909).jpg.webp) Sommer (Summer) (around 1920)

Sommer (Summer) (around 1920) Windstoss (Gust of wind) (1916)

Windstoss (Gust of wind) (1916) Meereslandschaft Tryptichon (Seaside landscape triptych) (before 1910)

Meereslandschaft Tryptichon (Seaside landscape triptych) (before 1910) Lichtgöttin (Light goddess) (around 1905)

Lichtgöttin (Light goddess) (around 1905) Weiblicher studienkopf (Female head, study) (1896)

Weiblicher studienkopf (Female head, study) (1896) Frauenkopf, en face (Female head, frontal view) (1897)

Frauenkopf, en face (Female head, frontal view) (1897) Das Welken (Withering) (1902)

Das Welken (Withering) (1902).jpg.webp) Erwachen (Awakening) (1926)

Erwachen (Awakening) (1926)

Bibliography

- Jutta Hülsewig-Johnen, Schönheit und Geheimnis. Der deutsche Symbolismus – Die andere Moderne, Bielefeld: Kerber Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86678-810-7

- A. Dehmer, M. Giebe, K. Krüger, '"Die Muse" von Hans Unger im Klingersaal: Bild und Rahmen im neuen Licht', Dresdener Kunstblätter, 4 (2010), p. 239-244

- Rolf Günther, Hans Unger. Leben und Werk mit dem Verzeichnis der Druckgraphik, Dresden: Neumeister Art Auctioneers, 1997 published at the occasion of the Hans Unger memorial exhibition in the Stadtmuseum of Freital from September 7 to October 26, 1997

- Hans-Günther Hartmann, Hans Unger, Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 1989, ISBN 3-364-00165-0

- Henner Menz, Hans Unger. Reisebilder aus dem Süden, Dresden: [sn], 1955[8]

- Eva Schmidt, "Hans Unger" in Katalog der Gemäldesammlung des Stadtmuseums Bautzen, 1954, pp. 117–118

- John Knittel, Hans Unger. Sonderausstellung Sächsischer Kunstverein, Dresden, 25. Januar-Mitte März 1933, Dresden [Brühlsche Terrasse]: Sächsischer Kunstverein, 1933

Much contemporary information on Hans Unger can be found in the German art magazine Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration,[9][10] now available on-line.[11] There is no complete survey of Unger's works. Some paintings are known only from photos, made and collected by Unger himself. Of some other paintings, the present whereabouts are unknown. The best source is the book by Günther quoted above.

References and sources

- Benezit Dictionary of Artists

- This article is based mainly on the exhibition catalogue by Günther from 1997, mentioned in the Bibliography section, and various articles in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration as mentioned also in this section. I submitted this article to Rolf Günther and he agreed with its contents.

- (de)galerie- schueller.de, profile

- The Estey Orgeln poster is mentioned in http://www.all-art.org/history661_posters.html

- (de)arcadja

- (de)munzinger.de, Hans Unger

- "Schönheit und Geheimnis der deutsche Symbolismus 24 03 13 07 07 13Beauty and MysteryGerman Symbolism 24 03 13 07 07 13 | Kunsthalle Bielefeld".

- in the library of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam

- ISSN 2195-6308

- See a.o. Maler Hans Unger - Loschwitz, by Richard Stiller, vol. 30 (1912), pp. 80-90

- NN (2011). "Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration". Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration: Illustr. Monatshefte für Moderne Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, Wohnungskunst U. Künstlerisches Frauen-Arbeiten. doi:10.11588/DIGLIT.6383.

On the 1997 exhibition in Freital, see the following articles:

- Hans Unger. Ein Künstler der Jahrhundertwende in Dresden, Weltkunst (vol. 18), September 15, 1997, pp. 1862–1864

- Erinnerung an Dresdens Malerfürsten, Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten, September 19, 1997

- Mäuschen Salome. Die Wiederentdeckung des Jugendstilmalers Hans Unger, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, September 25, 1997

- Der Traum von Arkadien, Städtische Zeitung Freital, October 17, 1997