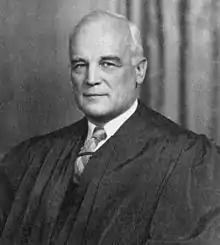

Harold H. Burton

Harold Hitz Burton (June 22, 1888 – October 28, 1964) was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 45th mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, as a U.S. Senator from Ohio, and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Harold H. Burton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office October 1, 1945 – October 13, 1958 | |

| Nominated by | Harry Truman |

| Preceded by | Owen Roberts |

| Succeeded by | Potter Stewart |

| Secretary of the Senate Republican Conference | |

| In office February 25, 1944 – September 30, 1945 | |

| Leader | Wallace White |

| Preceded by | Wallace White |

| Succeeded by | Chandler Gurney |

| United States Senator from Ohio | |

| In office January 3, 1941 – September 30, 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Vic Donahey |

| Succeeded by | James Huffman |

| 45th Mayor of Cleveland | |

| In office 1936–1940 | |

| Preceded by | Harry Davis |

| Succeeded by | Edward Blythin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 22, 1888 Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | October 28, 1964 (aged 76) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Selma Smith (m. 1912) |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | Bowdoin College (AB) Harvard University (LLB) |

| Signature | |

Born in Boston, Burton practiced law in Cleveland after graduating from Harvard Law School. After serving in the United States Army during World War I, Burton became active in Republican Party politics and won election to the Ohio House of Representatives. After serving as the mayor of Cleveland, Burton won election to the United States Senate in 1940. After the retirement of Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts, President Harry S. Truman successfully nominated Burton to the Supreme Court. Burton served on the Court until 1958, when he was succeeded by Potter Stewart.

Burton was known as a dispassionate, pragmatic, somewhat plodding jurist who preferred to rule on technical and procedural rather than constitutional grounds. He was also seen as an affable justice who helped ease tension on the court during an extremely acrimonious time. He wrote the majority opinion in Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath (1951) and Lorain Journal Co. v. United States (1951). He also helped shape the Court's unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Early life

Harold Hitz Burton was born in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, the second son of Anna Gertrude (Hitz) and Alfred E. Burton. His older brother was named Felix Arnold Burton. Harold's father was an engineer and the first Dean of Student Affairs at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1902-1921), reporting to the president. He taught at MIT before being selected as dean. As a former explorer, Burton had accompanied Robert Peary on several expeditions to the North Pole.[1]

Harold's mother died young. In 1906, his father married Lena Yates, a poet and artist from England[2] who later took the name of Jeanne D'Orge. They met that year on a walking trip in France. Yates published children's books as Lena Dalkeith. The couple had three children: Christine, Virginia (1909-1968), and Alexander Ross Burton.[1] The half siblings developed warm relationships over time. Virginia became an author and illustrator.[2]

Burton attended Bowdoin College, where he was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society,[3] was quarterback of the football team, and graduated summa cum laude.[4] His roommate and Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity (Theta chapter) brother was Owen Brewster, later a U.S. Senator from Maine. Burton went on to Harvard Law School, graduating in 1912.

Felix Arnold Burton became an architect after also attending Bowdoin. The Burton brothers and J. Edgar Hoover were second cousins on their mothers' side. Their common great-grandparents were Johannes (Hans) Hitz, first Swiss Consul General to the United States, and his wife Anna Kohler.

Marriage and family

Burton married Selma Florence Smith in 1912. They had four children: Barbara (Mrs. Charles Weidner), William (who served on the USS Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413) during WWII, in the Ohio House of Representatives and was a noted trial lawyer), Deborah (Mrs. Wallace Adler), and Robert (a distinguished attorney and counsel to athletes).

Early career

After graduation and marriage, Burton moved with his wife to Cleveland and began the practice of law there. However, in 1914, he joined his wife's uncle as a company attorney for Utah Power and Light Company in Salt Lake City. He later worked for Utah Light and Traction, and then for Idaho Power Company and Boise Valley Traction Company, both in Boise, Idaho.[5]

When the U.S. entered World War I, Burton joined the United States Army, rising to the rank of Captain. He served as an infantry operations officer in the 361st Infantry Regiment, 91st Infantry Division, and saw heavy action in France and Belgium. He received the Belgian Croix de guerre for gallantry in the push from the Lys and an individual citation from General Pershing for “meritorious and conspicuous services” during the Argonne Offensive.[5] After the war, Burton wrote the official history of his regiment, “600 Days’ Service,” and joined several veterans' organizations, including the Army and Navy Union, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and the American Legion.

Once back in the United States, Burton returned with his family to Cleveland, where he resumed his law practice. He also taught at Western Reserve University Law School.

Politics

In the late 1920s, Burton entered politics as a Republican. He was elected to the East Cleveland Board of Education in 1927 and to the Ohio House of Representatives in 1928. After serving briefly in the Ohio House, he became law director for the City of Cleveland in 1929 before returning to private practice in 1932.[5]

In 1935, Burton was elected mayor of Cleveland. He worked on issues of continuing assimilation of immigrant populations, supporting industry in the city, and dealing with transportation needs. Re-elected twice, he served until entering the U.S. Senate in 1941. For his decorous personal life and opposition to organized crime, he was dubbed "the Boy Scout Mayor."[5]

In 1940, Burton was elected to the U.S. Senate, with 52.3% of the vote, defeating John McSweeney.[6] He served on the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, which monitored the U.S. war effort during World War II. Also on the committee was then-Senator Harry S. Truman.

Supreme Court

Nomination

Justice Owen J. Roberts announced his resignation from the Supreme Court on June 30, 1945, effective July 31, 1945.[7] President Truman decided, as a bipartisan gesture, to appoint a Republican to replace him. He selected Burton as someone whom he knew and respected.[8] Burton's nomination was presented to the Senate Judiciary Committee on September 18, and the Senate unanimously approved it the next day.[9] Burton resigned from the Senate on September 30, 1945,[10] and was sworn in as an associate justice of the Supreme Court on October 1.[11] Burton was the last sitting member of Congress to be appointed to the Court. (Sherman Minton, a former senator, was appointed in 1949.)[12]

Judicial philosophy and working style

According to biographer Eric W. Rise, Burton appeared to lack an overarching judicial philosophy. He favored judicial restraint and most of his decisions were based on narrow procedural grounds rather than the Constitution. His judicial restraint, however, was informed by his political views, not by a legal philosophy, and he tended to defer to legislative and executive branch judgments because he agreed with them personally.[13] This pragmatism won him the respect of his fellow justices,[14] and served as a unifying influence on the Court[15] when the other justices were split on constitutional issues but could come together on technical or procedural grounds.[16]

From 1945 to 1953, Burton was usually in the centrist majority on the court, sometimes finding himself in a slightly more conservative majority on some issues.[17] He was part of the "Vinson bloc", which included Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson and Associate Justices Tom C. Clark, Sherman Minton, and Stanley Forman Reed. These five voted together 75 percent of the time in non-unanimous decisions.[18] However, beginning with the appointment of Earl Warren as Chief Justice in 1953, and more so after the appointment of William J. Brennan Jr. in 1956, Burton found himself increasingly in the minority.[17]

Burton biographer Mary Frances Berry has written that Burton knew "he was not brilliant and that writing came hard", and therefore not only worked very hard on his decisions but attempted to show this work by outlining all the precedents he had considered before reaching a conclusion.[19] Burton insisted on having all precedents researched before writing his opinions, wrote the first draft of his opinions himself,[16] and was well known for working long hours in his office.[20] His hard work earned him respect and praise from his colleagues,[14][21] but his working style also limited his judicial output.[16] Outside the Court, the press and some prominent legal scholars depicted Burton as mediocre, plodding, a weak legal mind, and more concerned with social activities.[16][14]

Burton was also very well-liked by all his colleagues, and his easy-going nature helped to ease tensions on the Court.[22]

Cold War, loyalty oath, and subversion rulings

The Cold War led state and federal governments to enact a wide variety of laws and regulations aimed at curbing espionage and subversion. Burton consistently showed deference to government restrictions on free speech, voting to uphold government action 27 out of 28 times.[18] He also wrote several important decisions. His basic approach toward these questions was judicial deference, as exemplified in his strong dissent in Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U.S. 304 (1946).[23] His first important majority opinion came in Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123 (1951), where a group had challenged the authority of the U.S. Attorney General to unilaterally declare groups to be Communist. Despite a significant split among the justices, Burton wrote a plurality decision in which he disposed of the case on technical grounds.[24] He argued that the listing was technically legal but that in a court of law the Attorney General had to offer evidence of subversion, which he had not.[25]

Burton also joined the majority in three important Fifth Amendment cases. In Emspak v. United States, 349 U.S. 190 (1955), he voted with the majority to extend the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination to testimony before congressional committees.[26][27] He also joined the majority in Ullmann v. United States, 350 U.S. 422 (1956), an important decision which upheld the Immunity Act of 1954 (which stripped the right against self-incrimination from persons given immunity from federal prosecution).[28] Burton's narrow procedural approach proved important in Beilan v. Board of Education, 357 U.S. 399 (1958). Two years earlier, six justices had formed a majority in Slochower v. Board of Higher Education of New York City, 350 U.S. 551 (1956), holding it unconstitutional for a school board to fire an employee for exercising their Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination. In Beilan, a teacher was dismissed not for exercising Fifth Amendment rights but for refusing to answer a question at all. Despite the retirement of Sherman Minton (who had joined his dissent in Slochower), Burton's narrow procedural approach in Beilan won over Justices Felix Frankfurter and John Marshall Harlan II and (with the support of new Justice Charles Evans Whittaker), Burton was able form a majority upholding the school district's action.[29]

At times, Burton's pragmatism could lead to important legislative outcomes. He joined the 7-to-1 majority in Jencks v. United States, 353 U.S. 657 (1957), in which the Court reversed the conviction of a labor leader under federal loyalty laws because the defendant was not given permission to view the evidence against him. Burton agreed with the majority, although he added the caveat that such evidence should first be reviewed by a district court judge to ensure that no national security secrets were revealed. Burton's view was subsequently adopted by Congress with passage of the Jencks Act in 1958.[25]

In one of his last opinions in the area, Burton voted to limit the application of the Smith Act in Yates v. United States, 354 U.S. 298 (1957). The majority had overturned the conviction of seven individuals using the "clear and present danger" First Amendment doctrine by concluding they had advocated violent overthrow of the government as an abstract doctrine, not as advocacy to action. Burton wrote an opinion concurring in the outcome, but cast his vote on narrow procedural grounds.[28]

Church and state

Generally, Burton favored a strict separation of church and state.[25] But his pragmatic approach to law sometimes caused him to dissent from majorities favoring a strict separation. For example, in Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947), Justice Hugo Black's 5-4 majority opinion held that while the Constitution required a strict separation between church and state, it was constitutionally permissible for a school district to reimburse parents when their children rode public school buses to religious schools so long as all such parents and religions were treated equally. Burton initially was predisposed to declare the law constitutional. Heavy lobbying from justices Felix Frankfurter, Robert H. Jackson, and Wiley Blount Rutledge changed his mind.[30] Burton dissented in the case not because he disagreed with Black's emphasis on the strict separation between church and state but because he believed that the state law violated the strict separation doctrine laid out by Black.[25]

The following year, Burton joined Black in the majority in McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U.S. 203 (1948). At issue was a state law which gave students "release time" to attend religious instruction on school grounds during the school day. The majority struck down the law as a violation of the First Amendment. Burton joined the majority only after Black agreed not to extend his ruling to release time programs that involved off-site religious instruction.[25][31]

Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S. 306 (1952), was factually similar to McCollum, although there was no instruction on school grounds. Although Burton's law clerks argued that the school was tacitly instructing children to attend religious classes, Burton disagreed, characterizing the dismissal as akin to excusing a child from school for a doctor's appointment. Burton joined the 6-to-3 majority.[32]

Criminal procedure

Burton was deferential to the state on criminal procedure and law-and-order issues.[25] Beginning with Betts v. Brady, 316 U.S. 455 (1942), the Supreme Court had ruled in a wide range of cases that except in cases of illiteracy, mental incapacity, or especially complicated cases, defendants did not have an absolute right to be informed of their right to counsel or to have counsel appointed for them by the state.[33] The Court had opportunity to revisit Betts in Bute v. Illinois, 333 U.S. 640 (1948), where a felon appealed his conviction because the trial court had not advised him of his right to counsel and because the plaintiff felt he had been rushed to trial, claims he felt violated constitutional guarantees to a fair trial and due process of law. Burton wrote for a 5-to-4 majority that the Constitution did not require a state to advise a defendant about his rights to counsel, or to provide such counsel, if the crime is not a capital offense.[34] Applying the 14th Amendment to the states in this area "would disregard the basic and historic power of the states to prescribe their own local court procedures," Burton wrote.[24] Yet, Bute was notable for carving out a capital-case exemption to Betts. Much criticized at the time for being inconsistent with Betts,[34] the Bute decision unintentionally established grounds for the Supreme Court to whittle away at Betts, so that by 1962 some legal scholars were already arguing the Court had effectively overruled Betts.[35] Betts and Bute were unanimously overruled in Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963).[36]

Another case decided the same year as Bute illustrates Burton's reliance on personal views as a guide to court action. Gilbert Thiel suffered a mental breakdown and leapt from a moving Southern Pacific Railroad passenger car, severely injuring himself. Thiel argued that railway personnel should have stopped him. The trial court blocked hourly-wage workers from being selected for the jury, which Thiel alleged biased the jury against him. Burton was powerfully motivated by a need to protect the Supreme Court's reputation, which he felt would be sullied if it approved such a distasteful practice. The majority in Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1946), narrowed its opinion to address only the facts regarding jury selection, and therefore did not decide whether the jury actually was biased against Thiel. This helped to win Burton's approval as well.[37]

Burton's belief that criminal procedure should be left to the states influenced his views in other cases as well. In Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956), a majority held that an indigent criminal defendant could not be denied transcripts of the trial. Burton wrote a dissent, joined by justices Minton, Harlan, and Reed, in which he strongly defended the federal nature of criminal procedure.[28] Burton also wrote a stinging dissent in Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947). The state of Louisiana attempted to execute convicted murderer Willie Francis on May 3, 1946, but the employee and assistant were both drunk while setting up the electric chair, and Francis did not die. The state sought to execute him again, but Francis claimed this violated the Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment.[38] The state's failure to execute Francis the first time should mark the end of the attempt, Burton wrote. Additional attempts constituted cruel and unusual punishment: "It is unthinkable that any state legislature in modern times would enact a statute expressly authorizing capital punishment by repeated applications of an electric current separated by intervals of days or hours until finally death shall result."[24] It was an opinion that showed "considerable foresight" regarding the Supreme Court's future capital punishment jurisprudence.[39]

Antitrust

Burton's greatest contribution to Supreme Court jurisprudence came in the area of antitrust law.[24] In American Tobacco Co. v. United States, 328 U.S. 781 (1946), Burton wrote for a near-unanimous court (Justice Rutledge had written a separate concurrence) that the Sherman Antitrust Act barred the mere existence of combinations or conspiracies which created monopolistic or oligopolistic market power, regardless of whether that power was actually used.[40] Legal scholar Eugene V. Rostow declared Burton's decision would usher in a new era of swift, effective antitrust enforcement.[40] But Burton's analysis cut both ways. In United States v. Columbia Steel Company, 334 U.S. 495 (1948), the same reasoning was used to allow U.S. Steel to buy out the much smaller Columbia Steel. Even though Columbia Steel was the largest steel manufacturer on the West Coast, Burton joined the majority in holding that the acquisition did not violate the Clayton Antitrust Act because Columbia Steel represented such a small percentage of overall American steel production.[41] The Columbia Steel decision shocked antitrust advocates.[42]

Yet, in Lorain Journal Co. v. United States, 342 U.S. 143 (1951), Burton wrote for a unanimous court that a monopoly could not use its power to retain its monopoly position. In that case, the Lorain Journal newspaper attempted to use its market power to prevent advertisers from placing ads with a new, competing radio station.[43] The case became noted for extending the federal government's antitrust power to local markets.[24] In Times-Picayune Publishing Co. v. United States, 345 U.S. 594 (1953), the majority held that the Times-Picayune newspaper did not violate the Sherman Antitrust Act by forcing advertisers to buy space in both its evening and morning editions. Burton (joined by Black, Douglas, and Minton) strongly dissented. The Sherman Act barred all monopolistic market power, he argued, whether it was used to create or maintain a monopoly, or whether it was used to harm the public (through monopolistic pricing) or users (as in the Times-Picayune "must buy" case).[44]

Burton wrote the lone dissent in Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc., 346 U.S. 356 (1953). A majority of the justices had disposed of the case in a per curiam decision, citing the ruling in Federal Baseball Club v. National League, 259 U.S. 200 (1922). Citing extensive statistics about the farm system, broadcasting revenues, and national advertising campaigns, Burton concluded it was unreasonable to claim that major league baseball was not engaged in interstate commerce. He strongly criticized the majority for incorrectly construing Federal Baseball Club, and said the majority was wrong to assume that because the Sherman Antitrust Act did not explicitly cover baseball that baseball was intended to be exempt.[45][46]

A notable exception to the broad application of antitrust law[24] came in Burton's dissent in United States v. E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 353 U.S. 586 (1957). The DuPont chemical company had purchased a substantial bloc of stock in General Motors. Subsequently, General Motors purchased most of its paints and fabrics from DuPont. A majority of the court held that this vertical integration constituted a violation of the Clayton Antitrust Act.[47] Burton, dissenting, was highly skeptical that the Clayton Act applied to vertical integration, and strongly criticized the majority's logic concerning market power. Burton found that DuPont simply didn't have the market power the majority claimed it did.[48] The dissent drew widespread praise from legal scholars.[24]

Racial segregation

Burton's other major contribution to Supreme Court jurisprudence came in the area of racial segregation.[24] Burton had been a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People from 1941 to 1945,[25][49] and was a dependable vote for civil rights on the high court.[50] One of the exceptions was his first civil rights case on the Court, Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 (1946). Burton was the lone dissenter in the case, which involved the racial segregation of interstate buses with curtains. Burton argued that, in the absence of a federal statute, each state should be free to establish its own laws on racial segregation.[17][51]

After his vote in Morgan, Court observers believed that Burton could not be counted on to vote to expand or protect civil rights.[52] It surprised legal analysts, then, when Burton joined the unanimous majority in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 US 1 (1948), a landmark case that held courts could not enforce racially-restrictive real estate covenants.[53]

In a string of votes over the next three years, Burton voted to undermine the "separate but equal" doctrine in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896). He joined the unanimous majority in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, in 1950, which held that "separate but equal" professional legal education was unconstitutional. Heman Marion Sweatt, an African American man, was refused admission to the all-white University of Texas School of Law. One of the first cases to find that "separate but equal" was not equal, the case deeply influenced the Court's opinion in Brown v. Board of Education four years later.[50] During the Sweatt deliberations, Burton came to the conclusion that Plessy v. Ferguson should be reversed.[54] He informed the other justices about his conclusion the during post-oral argument conference on Sweatt.[55] The same year, Burton joined the unanimous majority in McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637, which racially desegregated all graduate schools in the United States on essentially the same grounds as Sweatt.[17] Burton subsequently wrote the unanimous majority opinion in Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816 (1950).[54] The case involved interstate travel on a passenger train. Henderson, an African-American federal worker, held a ticket that cost the same and allegedly provided the same level of service as a ticket sold to a white passenger. Nevertheless, Henderson was denied seating in the dining car after attendants seated white passengers at the tables reserved for blacks. Although the Sweatt and McLaurin courts had ruled on constitutional grounds, Burton hesitated to do so if there were procedural or technical grounds available.[16] In Henderson, Burton was able to form a unanimous majority by basing his decision on the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, rather than the 14th Amendment.[16]

By 1953, Burton's thinking on racial segregation had evolved to embrace a constitutional attack on Plessy. That year, the Supreme Court took up Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461, a case in which a whites-only private political club dominated the local Democratic primary election in an electoral district where Republicans were not competitive. This system served to disenfranchise black voters. The federal district and appellate courts had upheld the constitutionality of the system, persuaded that the club was purely private and thus no state action was involved. At the first post-oral argument conference held by the justices, Burton was adamant that the Supreme Court reverse and declare the practice unconstitutional.[56] The justices took a widely varying approach to the case. The opinion of the Court was authored by Hugo Black, and joined only by Burton and Douglas. Frankfurter, personally at odds with Black, authored a separate opinion agreeing with Black's, but which he refused to have listed as "concurring". Clark authored a concurrence, which was joined by Vinson, Reed, and Jackson. Surprisingly, Burton joined Black in declaring the whites-only club in violation of the 15th Amendment. Black won over all but one justice (Minton) by agreeing to remand the case to the district court for a solution, but not specifying what that solution should be.[56]

Role in Brown v. Board of Education

Burton played a crucial role in the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). Several cases alleging unconstitutional racial discrimination in elementary and secondary public schools were coming before the court in 1952. In the first sign that Burton was ready to reverse Plessy, on June 7 he voted with Clark and Minton to grant certiorari to both Brown and another case, Briggs v. Elliott, 342 U.S. 350 (1952).[57] The Supreme Court subsequently agreed to also hear Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954), Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 103 F. Supp. 337 (1952), and Gebhart v. Belton, 91 A.2d 137 (Del. 1952). Oral argument in all five cases was heard in early December 1952.[58] The justices held their first post-oral argument judicial conference on the cases on December 13.[59] Burton, Black, Douglas, and Minton had all come out against racial segregation in the public schools during the conference.[60] Clark seemed unsure, but it appeared that he could be persuaded to join the majority.[61] Burton himself noted in his diary that he felt the court was likely to vote 6-to-3 to bar racial discrimination in schools, but not on constitutional grounds.[62] Other justices were not so sure. William O. Douglas believed that five justices would vote to uphold Plessy: Vinson, Clark, Frankfurter, Jackson and Reed. Among these, Frankfurter and Jackson exhibited the most doubt about Plessy.[63] Douglas even worried that a 5-to-4 decision would be reached in which schools would be given a decade or more to bring unequal African American schools up to par.[64] Vinson was a fence-sitter of a different kind: he was deeply troubled by the effect a desegregation order would have on the nation. It was likely that, even if Vinson joined a majority in barring "separate but equal" in public schools, he would do so only on narrow, technical grounds—leading to a plurality decision, a fragmented court, and a ruling lacking in legal and moral weight.[65][64] Frankfurter, who personally believed racial segregation to be "odious",[66] argued for the cases to be held over to the next term and reargued.[67] A majority of the court agreed. Some hoped for changes in the political landscape that would make a decision easier, while others worried about the effect a divided opinion would have.[64] On June 8, the Supreme Court issued its order, scheduling reargument for October 12, 1953.[67]

Chief Justice Fred Vinson died unexpectedly of a heart attack on September 8, 1953.[68] On September 30, President Eisenhower nominated Earl Warren, the outgoing Republican governor of California, to replace Vinson as Chief Justice.[69] The news was not unexpected; Warren had declined a fourth term as governor on September 2, and he had long been seen as a favorite for a Supreme Court nomination.[70] Warren's was a recess appointment, which meant he would have to give up his seat unless the Senate confirmed him before the end of its next session. Warren was sworn in as Chief Justice on October 5.[71] Warren's nomination was sent to the Senate on January 11, 1954. Senator William Langer, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, kept the nomination bottled up for seven weeks in order to hold hearings on unsubstantiated charges that Warren was a Marxist and controlled by the California liquor lobby.[72] Warren's nomination was forwarded to the Senate on February 24 on a favorable 12-to-3 vote,[73] and the Senate confirmed him on March 1 on a voice vote after just eight minutes of discussion.[72]

Even before oral reargument, Warren was convinced that Plessy had to be reversed and racial discrimination in public education ended.[74] Warren perceived Burton as a key ally in overturning Plessy. Immediately after his swearing-in ceremony, Warren worked hard to become as friendly as possible with Burton, quietly seeking him out before any of the more senior justices. (Had Warren's actions become widely known, he would have offended court tradition and the other justices.)[75]

Reargument in Brown and the other cases was set for early December 1953.[76] The first post-oral reargument conference was held December 12,[77] at which time Warren made it very clear he would join Black, Burton, Douglas, and Minton in voting to overturn Plessy. Warren believed a unanimous decision in Brown was necessary to win public acceptance for the decision.[78][79] Stanley Forman Reed appeared to Warren to be the justice most comfortable with segregation and Plessy, but even Reed admitted on December 12 that what was constitutional in 1896 might not be in 1953, due to changing circumstances.[77] Warren went to work on Reed immediately. During the lunch break on December 12, Warren invited Reed to lunch, accompanied by Burton, Black, Minton, and Douglas. The social pressure on Reed continued for the next five days, as he lunched daily with Warren, Burton, Black, and Minton.[80] Burton wholeheartedly supported Warren's attempt to forge a unanimous majority,[16] and Warren accurately judged Burton to be his most valuable ally. Burton not only pushed for pragmatic solutions, which helped win over Reed, but proved to be articulate, passionate, and persuasive[81]—which few on the Court expected.[19] As the justices continued to debate its approach to Brown and the other cases in conferences, in memoranda, and privately among themselves, Burton worked to alleviate fears about implementation by talking freely about his experiences as mayor of Cleveland. Burton had ended racial discrimination in healthcare by hiring African American nurses to work in whites-only hospitals. This had gone relatively smoothly, and black nurses earned widespread respect among white citizens for their professionalism.[82]

The efforts of Warren and Burton paid off. The Supreme Court handed down a unanimous decision in Brown on May 17, 1954. Pragmatically, Warren declined to overturn Plessy, but argued that it did not apply to the field of public education. Implementation of the decision was left up to district courts, at a later date.[83]

During part of his time on the Supreme Court, Burton kept notes on all judicial conferences as well as a diary in which he documented the discussions he had with other justices. Burton's diary has proven to be an invaluable resource in understanding how Earl Warren achieved unanimity on Brown.[54]

Resignation

By June 1957, Burton began suffering from significant shaking in his hands. As the October 1957 term began, his handwriting became difficult to read, and he began taking longer afternoon naps.[84] He was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. The shaking in his left arm had become so severe by the start of 1958 that he decided to retire from the Supreme Court. He informed President Dwight D. Eisenhower of his decision in March. Worried about other domestic and international events, Eisenhower asked Burton to consider staying one more year, and make no public announcement. Burton agreed. In the meantime, arrangements were made to give Burton's law clerks positions at the United States Department of Justice should Burton retire before the end of the October 1958 Supreme Court term.[85]

Burton's condition worsened, and in June 1958 he was advised by his doctors to retire. Burton informed Chief Justice Earl Warren of his decision, and Warren urged him to stay on the Court at least until September 30. A week later, Attorney General William P. Rogers met with Burton to discuss rumors that Burton was retiring. Once more, Burton reiterated his desire to leave the Court, and Rogers, too, asked him to remain until September 30.[84] Various crises and events conspired to keep Burton from meeting with the president until July 17,[84] at which time Burton privately informed Eisenhower of his intention to resign. (Burton had turned 70 years old on June 22, enabling him to retire at full pay.)[85]

Eisenhower asked Burton to keep the resignation private for a time. In part, this was because Eisenhower wanted time to consider a replacement without public pressure. Additionally, Eisenhower was worried that a resignation now might create unnecessary complications for the Supreme Court, which had agreed to hear Cooper v. Aaron.[85] This case concerned the Little Rock Nine, a group of African American students barred from enrolling at Little Rock Central High School by Orval Faubus, the Governor of Arkansas. William G. Cooper and other members of the Little Rock school district board of education had alleged they could not implement the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), because of public hostility and the opposition of Governor Faubus and the state legislature.[85] The case was clearly headed for the Supreme Court: A local court had ruled in favor of the school district, and the NAACP had appealed both to an Arkansas circuit court and the U.S. Supreme Court (which, on June 30, declined to hear the appeal until the circuit court had ruled but which also had advised the circuit court to rule swiftly—before the school year began).[86]

The Supreme Court held a special summer session on September 11 and issued its decision on September 29,[87] after which Burton informed his law clerks and the rest of the Supreme Court of his decision to retire.[88]

Burton publicly announced his retirement from the Supreme Court on October 6, 1958.[89] Burton publicly announced that he was suffering from Parkinson's disease. He retired on the advice of physicians, who said the condition might improve without the stress from his Court position.[90] His last day at the Supreme Court was October 13.[91]

Retirement

Following his retirement from the Supreme Court, Burton sat by designation for several years on panels of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

He died on October 28, 1964, in Washington, D.C., from complications arising from Parkinson's disease, kidney failure, and pulmonary trouble. His remains were interred at Highland Park Cemetery in Cleveland.[92][93]

Legacy

Cleveland's Main Avenue Bridge was renamed in his honor in 1986.

His papers and other memorabilia are primarily in four collections. Bowdoin College has 750 items including documents concerning 47 judicial opinions.[94][95] The Hiram College Archives collection holds 69 items. The Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress has 187 ft. (120,000 items) consisting mainly of correspondence and legal files. The Western Reserve Historical Society has 10 linear ft. relating mainly to his tenure as mayor of Cleveland; the collection contains correspondence, reports, speeches, proclamations, and newspaper clippings relating to routine administrative matters and topics of special interest during Burton's mayoralty. Other papers repose at various institutions around the country, as part of other collections.[95]

See also

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 8)

- List of members of the American Legion

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Stone Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Vinson Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Warren Court

References

- Barbara Elleman, Virginia Lee Burton: A Life in Art, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2002, pp. 7-9

- "Virginia Lee Burton", Gloucester Lyceum & Sawyer Free Library

- Supreme Court Justices Who Are Phi Beta Kappa Members Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Phi Beta Kappa website, accessed Oct 4, 2009

- HAROLD HITZ BURTON: MAYOR, SENATOR, & SUPREME COURT JUSTICE Archived January 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 2, 2011.

- Harold Hitz Burton biography at the Ohio Judicial Center Archived May 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 2, 2011

- Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives, Statistics of the Presidential and Congressional Election of November 5, 1940, p. 24

- "The President's News Conference," July 5, 1945. Harry S. Truman". The American Presidency Project. 2017. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- Walker 2012, p. 159.

- McMillion, Barry J. (January 28, 2022). Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2020: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- "Huffman Named Senate By Lausche". The Plain Dealer. October 8, 1945. pp. 1, 4.

- "Supreme Court To Seat Burton As First Task". The Washington Post. October 1, 1945. p. 6.

- Rutkus 2009, p. 19.

- Rise 2006, p. 101.

- Smith 2005, p. 116.

- West's Encyclopedia of American Law 1998, p. 175.

- Rise 2006, p. 103.

- Hall 2001, p. 336.

- Kluger 2004, p. 587.

- Berry 1978, pp. 48–49.

- Hoffer, Hoffer & Hull 2007, p. 286.

- Newton 2006, p. 264.

- Newton 2006, p. 263.

- Cantor 2017, p. ix.

- "Harold H. Burton Is Dead at 76". The New York Times. October 29, 1964. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- Rise 2006, p. 102.

- Atwell 2002, pp. 71–72.

- "Constitutional law... contempt of Congress". American Bar Association Journal. September 1955. p. 849. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- Atwell 2002, p. 72.

- Rise 2006, pp. 101–102.

- Dickson 2001, p. 402.

- Dickson 2001, p. 404.

- Dickson 2001, p. 405.

- Israel 1975, pp. 91–93.

- Israel 1975, pp. 111–112.

- Israel 1975, p. 122.

- Israel 1975, pp. 93–95.

- Dickson 2001, pp. 562–564.

- King, Gilbert (July 19, 2006). "The Two Executions of Willie Francis". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- Dickson 2001, p. 101.

- Peritz 2001, pp. 175–176.

- Peritz 2001, pp. 176–177.

- Peritz 2001, p. 176.

- Hixson 1989, p. 72.

- Hixson 1989, p. 75.

- Banner 2013, pp. 118–120.

- Dickson 2001, p. 146.

- Alese 2016, p. 496.

- Ross 1993, p. 377.

- "Burton Was Hard Worker for City, U.S.". The Plain Dealer. October 29, 1964. p. 8.

- Lavergne 2010, p. 270.

- Kluger 2004, p. 242.

- Kluger 2004, p. 248.

- Dickson 2001, pp. 698–699.

- Atwell 2002, p. 71.

- Dickson 2001, p. 643.

- Dickson 2001, pp. 839–840.

- Kluger 2004, p. 541.

- Cottrol, Diamond & Ware 2003, p. 248.

- Emanuel 2011, p. 157.

- Newton 2006, p. 311.

- Patterson 2002, p. 64.

- Patterson 2002, p. 56.

- Zelden 2013, pp. 78–79.

- Wrightsman 2008, p. 119.

- Zelden 2013, pp. 79–80.

- Zelden 2013, p. 79.

- Coleman & Bliss 2010, p. 143.

- "Chief Justice Vinson Dies of Heart Attack in Capital". The New York Times. September 8, 1953. pp. 1, 18.

- Reston, James (October 1, 1953). "Eisenhower Names Warren to be Chief Justice of U.S.". The New York Times. pp. 1, 14.

- Davies, Lawrence E. (September 4, 1953). "Warren Bars 4th Term Bid". The New York Times. pp. 1, 8.

- Huston, Luther A. (October 6, 1953). "Warren Sworn In". The New York Times. pp. 1, 21.

- "Senate Confirms Warren By Voice Vote". The New York Times. March 2, 1954. p. 13.

- Huston, Luther A. (February 25, 1954). "Committee Backs Warren By 12 to 3". The New York Times. pp. 1, 14.

- Zelden 2013, p. 80.

- Newton 2006, p. 277.

- Kluger 2004, p. 790.

- Zelden 2013, p. 83.

- Jost 1998, p. 310.

- Kluger 2004, pp. 689–701.

- Newton 2006, p. 313.

- Dickson 2001, p. 646.

- Dickson 2001, pp. 646, 653.

- Zelden 2013, p. 85.

- Ward 2003, p. 163.

- Smith 2005, pp. 116–117.

- Whittington 2004, pp. 16–18.

- Whittington 2004, p. 17.

- Smith 2005, p. 117.

- Folliard, Edward T. (October 7, 1958). "Justice Burton Retiring From Supreme Court". The Washington Post. p. A1.

- "Ailment Affects Arm Of Burton". The Washington Post. October 9, 1958. p. A2.

- "Burton Leaves Court With Justices' Praise". The Washington Post. October 14, 1958. p. B6.

- "Christensen, George A. (1983) Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices, Yearbook". Archived from the original on September 3, 2005. Retrieved April 26, 2010. Supreme Court Historical Society at Internet Archive.

- Christensen, George A., "Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited", Journal of Supreme Court History, Volume 33 Issue 1, Pages 17–41 (Feb 19, 2008), University of Alabama.

- "Harold Hitz Burton Papers at Bowdoin College". Archived from the original on January 4, 2004. Retrieved March 24, 2004.

- "Federal Judicial Center, Resources, Harold Hitz Burton". Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

Bibliography

- Alese, Femi (2016). Federal Antitrust and EC Competition Law Analysis. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781138262287.

- Atwell, Mary Welek (2002). "Burton, Harold Hitz". In Schultz, David A. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of American Law. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 9781438109916.

- Banner, Stuart (2013). The Baseball Trust: A History of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199389728.

- Berry, Mary Frances (1978). Stability, Security, and Continuity: Mr. Justice Burton and Decision-Making in the Supreme Court (1945–1958). Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780837197982.

- Cantor, Milton (2017). The First Amendment Under Fire: America's Radicals, Congress, and the Courts. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412863414.

- Coleman, William T.; Bliss, Donald T. (2010). Counsel for the Situation: Shaping the Law to Realize America's Promise. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 9780815704881.

- Cottrol, Robert J.; Diamond, Raymond T.; Ware, Leland (2003). Brown v. Board of Education: Caste, Culture, and the Constitution. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700612888.

- Dickson, Del (2001). The Supreme Court in Conference, 1940-1985: The Private Discussions Behind Nearly 300 Supreme Court Decisions. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195126327.

- Emanuel, Anne (2011). Elbert Parr Tuttle: Chief Jurist of the Civil Rights Revolution. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820339474.

- Hall, Timothy L. (2001). Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 9780816041947.

- Hixson, Richard F. (1989). Mass Media and the Constitution: An Encyclopedia of Supreme Court Decisions. New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 9780824079475.

- Hoffer, Peter Charles; Hoffer, William James; Hull, N.E.H. (2007). The Supreme Court: An Essential History. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700615384.

- Israel, Jerold H. (1975). "Gideon v. Wainright: The "Art" of Overruling (1963)". In Kurland, Philip B. (ed.). The Supreme Court and the Judicial Function. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226464015.

- Jost, Kenneth (1998). The Supreme Court A-Z. New York: Routledge. ISBN 1-57958-124-2.

- Kluger, Richard (2004). Simple Justice: The History of 'Brown v. Board of Education' and Black America's Struggle for Equality. New York: Knopf. ISBN 9780375414770.

- Lavergne, Gary M. (2010). Before Brown: Herman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall, and the Long Road to Justice. Austin, Tex.: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292742956.

- Newton, Jim (2006). Justice for All: Earl Warren and the Nation He Made. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781436247412.

- Patterson, James T. (2002). Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195156324.

- Peritz, Rudolph J.R. (2001). Competition Policy in America: History, Rhetoric, Law. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195144093.

- Ross, Stephen F. (1993). Principles of Antitrust Law. Westbury, N.Y.: Foundation Press. ISBN 9781566620031.

- Rutkus, Denis Steven (May 6, 2009). Supreme Court Appointment Process: Roles of the President, Judiciary Committee, and Senate. 09-RL-31989 (Report). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress.

- Rise, Eric W. (2006). "Harold Hitz Burton". In Urofsky, Melvin I. (ed.). Biographical Encyclopedia of the Supreme Court: The Lives and Legal Philosophies of the Justices. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. ISBN 9781933116488.

- Smith, Craig Alan (2005). Failing Justice: Charles Evans Whittaker on the Supreme Court. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN 9780786421978.

- Walker, Samuel (2012). Presidents and Civil Liberties From Wilson to Obama: A Story of Poor Custodians. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107677081.

- Ward, Artemus (2003). Deciding to Leave: The Politics of Retirement From the United States Supreme Court. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9781417523979.

- West's Encyclopedia of American Law. Volume 2. Minneapolis: West Publishing Co. 1998. ISBN 9780314055385.

- Whittington, Keith E. (2004). "The Court As the Final Arbiter of the Constitution". In Ivers, Gregg; McGuire, Kevin T. (eds.). Creating Constitutional Change: Clashes Over Power and Liberty in the Supreme Court. Charlottesville, Va.: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 9780813923024.

- Wrightsman, Lawrence (2008). Oral Arguments Before the Supreme Court: An Empirical Approach. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195368628.

- Zelden, Charles (2013). Thurgood Marshall: Race, Rights, and the Struggle for a More Perfect Union. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415506427.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J., Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court. 3d. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992). ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare, The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies,1789–1995 (2nd ed.) (Supreme Court Historical Society), (Congressional Quarterly Books, 2001) ISBN 1-56802-126-7; ISBN 978-1-56802-126-3.

- Forrester, Ray. (October 1945) "Mr. Justice Burton and the Supreme Court" New Orleans: Tulane Law Review.

- Frank, John P., The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions (Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, editors) (Chelsea House Publishers: 1995) ISBN 0-7910-1377-4, ISBN 978-0-7910-1377-9.

- Martin, Fenton S. and Goehlert, Robert U., The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography, (Congressional Quarterly Books, 1990). ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

External links

- Ohio Judicial Center, Harold Hitz Burton.

- Harold Hitz Burton, in Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography

- Harold Hitz Burton, Timeline of the Court at

- Harold Hitz Burton at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- United States Congress. "Harold H. Burton (id: B001150)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.