Harold Keller

Harold Paul Keller (August 3, 1921 – March 13, 1979) was a United States Marine corporal who was wounded in action during the Bougainville campaign in World War II. During the Battle of Iwo Jima, he was a member of the patrol that captured the top of Mount Suribachi and raised the first U.S. flag on Iwo Jima on February 23, 1945. He is one of the six Marines who raised the larger replacement flag on the mountaintop the same day as shown in the iconic photograph Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima.

Harold Keller | |

|---|---|

Harold Keller circa 1945 | |

| Nickname(s) | "Pie" |

| Born | August 3, 1921 Brooklyn, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | March 13, 1979 (aged 57) Grinnell, Iowa, U.S. |

| Buried | Brooklyn Memorial Cemetery, Brooklyn, Iowa |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Marine Corps |

| Years of service | 1942–1945 |

| Rank | Corporal |

| Unit | Company E, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, 5th Marine Division |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Purple Heart |

The first flag flown over Mount Suribachi at the south end of Iwo Jima was regarded to be too small to be seen by the thousands of Marines fighting on the other side of the mountain, so it was replaced by the second one. Although there were photographs taken of the first flag flying on Mount Suribachi, there is no photograph of Marines raising the first flag. The second flag raising became famous and took precedence over the first flag-raising after copies of the second flag-raising photograph appeared in newspapers two days later. The second flag raising was also filmed in color.[1]

Keller was not recognized as one of the second flag-raisers until the Marine Corps announced on October 16, 2019, after an investigation, that he was in the historic photograph taken by combat photographer Joe Rosenthal of the Associated Press. The Marine Corps also stated that Keller was incorrectly identified as Private First Class Rene Gagnon in the photograph, who they determined is not in the photo.[2] Keller is one of three Marines in the photograph who were not originally identified as flag raisers.[3]

The Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia, is modeled after the photograph of six Marines raising the second flag on Iwo Jima.[4]

U.S. Marine Corps

Harold Keller was born on August 3, 1921, in Brooklyn, Iowa. Keller graduated from Brooklyn High School. On January 2, 1942, he enlisted in the Marine Corps and attended training at Camp Elliott in San Diego and later training in Honolulu, Hawaii. Keller was assigned to the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson and was present for the Battle of Midway and took part in the fighting at Guadalcanal. In 1943, Keller was shot through his right shoulder at Bougainville.[5]

In February 1944, the Marine Raiders were disbanded. Keller met and subsequently married his wife, Ruby O'Halloran, while he was home on leave. Keller was next assigned to Easy (E) Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division which was activated at Camp Pendleton in 1944. In September, the division was sent to Camp Tarawa near Hilo, Hawaii, for further training to prepare for the invasion of Iwo Jima. In January 1945, the division left Hawaii and sailed for Iwo Jima. Keller participated in the battle of Iwo Jima, which began on February 19 and ended on March 26. On February 23, he was part of the 40-man patrol that ascended Mount Suribachi and raised the Second Battalion's flag on top. Later that day, he was one of the six Marines that raised a second and larger flag on top.[5]

First flag raising

At 8:00 am on February 23, 1945, Lt. Colonel Chandler W. Johnson, the Second Battalion, 28th Marines, commander, ordered a platoon-size patrol to climb up Mount Suribachi to seize and occupy the crest. Captain Dave Severance, E Company's commander, then assembled the remainder of his Third Platoon and other members of the battalion which included two Navy corpsmen and stretcher bearers. First Lieutenant Harold Schrier, E Company's executive officer, who volunteered to lead the patrol, was to raise the battalion's American flag if possible to signal that the mountaintop was secure. The patrol left at about 8:30. Along the way up which was difficult climbing at times, there was a small number of shots from Japanese snipers. When Lt. Schrier and his men reached the rim of the volcano, there was a skirmish which they soon overcame. After a Japanese iron water pipe was found to use as a flagpole, the battalion's American flag was tied to it by Lt. Schrier, Sergeant Henry Hansen, and Corporal Charles Lindberg.

Once the flag was tied on, the flagstaff was raised about 10:30 by Lt. Schrier, Platoon Sergeant Ernest Thomas, Sgt. Hansen,[6] and Cpl. Lindberg. Seeing the raising of the national colors immediately caused loud cheers from the Marines, sailors, and Coast Guardsmen on the south end of Iwo Jima and from the men on the ships near the beach. Due to the terrific winds and soft ground on the mountaintop, Private Phil Ward and Navy corpsman John Bradley pitched in afterwards to help keep the flagstaff vertical. Staff Sergeant Lou Lowery, a Marine photographer for "Leatherneck Magazine" and the only photographer who accompanied the patrol, took several photos of the first flag before and after it was raised. The last photo he took on the mountaintop was before a Japanese grenade caused him to fall several feet down the side of the crater and break his camera (his film was not damaged). The Marine Corps did not allow any of his photos to be published until 1947, in Leatherneck Magazine. Platoon Sgt. Thomas was killed on March 3 and Sgt. Hansen on March 1. Cpl. Lindberg was wounded on March 13.

Second flag raising

Two hours after the first flag was raised on Mount Suribachi, Marine Corps leaders decided that in order for the American flag to be better seen on the other side of Mount Suribachi by the thousands of Marines fighting there to capture the island, another larger flag should be flown on Mount Suribachi (Lt. Col. Johnson also wanted to secure the flag for his battalion). Under Lt. Col. Johnson's orders, Captain Severance ordered Sergeant Michael Strank a rifle squad leader from Second Platoon, to take three of his Marines to the top of Mount Suribachi and raise the second flag. Sgt. Strank chose Corporal Harlon Block, Private First Class Ira Hayes, and Private First Class Franklin Sousley. Private First Class Rene Gagnon, a Second Battalion runner (messenger) for E Company, was ordered to take the replacement flag up the mountain and return the first flag to the battalion adjutant.[7]

When Sgt. Strank with his three Marines got to the top with communication wire (or supplies), Pfc. Hayes and Pfc. Sousley found a Japanese steel pipe to attach the flag on. After they took the pipe to Sgt. Strank and Cpl. Block, the replacement flag was attached to the pipe which was near the other flag. As the four Marines were about to raise the flagstaff, Sgt. Strank and Cpl. Block called out to two nearby Marines from Lt. Schrier's patrol, Private First Class Harold Schultz and Private First Class Keller, to help them raise the flagstaff.[8] Lt. Schrier then ordered the six Marines to raise the second flag while Pfc. Gagnon and three Marines lowered the first flagstaff.[3] In order to keep the flagstaff in a vertical position, Sgt. Strank and his three Marines held it while rocks were added by Pfc. Keller, Pfc. Schultz, and others around the base of the flagstaff. The flagstaff then was stabilized with three guy-ropes.

Associated Press combat photographer Joe Rosenthal had climbed up the mountain with two Marine photographers (Marine Sergeant Bill Genaust and Private Robert Campbell) in time to photograph the first flag while it was still up. This also enabled him to take the famous black-and-white photograph of the second-flag raising; Rosenthal's second flag raising photograph started appearing in newspapers on Sunday, February 25, 1945. Other combat photographers, including Pfc. George Burns, an army photographer (from Yank Magazine) and a Coast Guard photographer, also climbed up Mount Suribachi after the first flag raising to take pictures including some of each flag flying. Lt. Colonel Johnson was killed on Iwo Jima on March 2 and Sgt. Bill Genaust, who filmed the second flag-raising in color, was killed in a cave on March 4. Sgt. Strank and Cpl. Block were killed on March 1 and Pfc. Sousley was killed on March 21.

Post-war life

Harold Keller survived the war and returned to his wife Ruby in Iowa. They raised two boys and one girl.

Though Keller virtually never spoke of the war, Marine researchers found evidence that he acknowledged the fact that he was one of the second flag raisers at least twice: first, in a letter to Ruby written from Iwo Jima in February or March 1945; and decades later, circa 1977, in a newsletter of his employer (a company called Surge) in which his participation is stated unambiguously. Additionally, Keller's private scrapbook contained a strongly-worded letter from Major General Philip H. Torrey, dated 17 September 1945, which suggests that Keller might have attempted to correct the record but was silenced.[3][Note 1]

Keller worked a series of jobs in his hometown and was also a member of the volunteer fire department in Brooklyn for 30 years, eventually becoming the fire chief. He died of a heart attack on March 13, 1979. He was buried in the Brooklyn Memorial Cemetery.[5]

Marine Corps War Memorial

The Marine Corps War Memorial (also known as the Iwo Jima Memorial) in Arlington, Virginia, was dedicated on November 10, 1954.[9] The monument was sculptured by Felix de Weldon from the photograph of the second flag raising on Mount Suribachi. Since October 23, 2016, Harold Keller is depicted as the second Marine figure from the base of the flagstaff on the memorial.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower sat upfront during the dedication ceremony with Vice President Richard Nixon, Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson, Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Anderson, and General Lemuel C. Shepherd, the 20th Commandant of the Marine Corps. Ira Hayes, one of the three surviving flag raisers (Hayes, Schultz, and Keller) depicted on the monument, was also seated upfront with John Bradley (incorrectly identified as a flag raiser until June 23, 2016),[8] Rene Gagnon (incorrectly identified as a flag raiser until October 16, 2019),[2] Mrs Martha Strank, Mrs. Ada Belle Block, and Mrs. Goldie Price (mother of Franklin Sousley).[10] Those giving remarks at the dedication included Robert Anderson, Chairman of Day; Colonel J.W. Moreau, U.S. Marine Corps (Retired), President, Marine Corps War Memorial Foundation; General Shepherd, who presented the memorial to the American people; Felix de Weldon; and Richard Nixon, who gave the dedication address.[11] Inscribed on the memorial are the following words:

- In Honor And Memory Of The Men of The United States Marine Corps Who Have Given Their Lives To Their Country Since 10 November 1775

Second flag-raising corrections

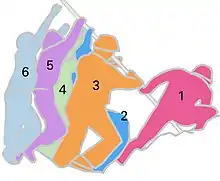

#1, Cpl. Harlon Block (KIA)

#2, Pfc. Harold Keller

#3, Pfc. Franklin Sousley (KIA)

#4, Sgt. Michael Strank (KIA)

#5, Pfc. Harold Schultz

#6, Pfc. Ira Hayes

On March 20, 1945, President Roosevelt ordered the flag-raisers in Rosenthal's photograph to Washington D.C. after the battle. Pfc. Gagnon was ordered to Washington and arrived on April 7. He was questioned the same day by a Marine public information officer about all the identities of the flag raisers in the photograph. He identified the six flag raisers as Sgt. Strank, Pfc. Sousley, Navy corpsman John Bradley, Pfc. Ira Hayes, and Sgt. Henry Hansen, and himself. He also said Sgt. Strank, Sgt. Hansen, and Pfc. Sousley were killed on Iwo Jima.[8] After Pfc. Gagnon was questioned, Pfc. Hayes and PhM2c. Bradley were ordered to Washington. Bradley, who was recovering from his wounds at Oakland Naval Hospital in Oakland, California, was transferred to Bethesda Naval Hospital at Bethesda, Maryland, where he was shown Rosenthal's flag-raising photograph and was told he was in it. Both Bradley (on crutches) and Hayes arrived in Washington on April 19. They reported to the same officer and were questioned separately. PhM2c. Bradley agreed with all of the identities of the flag-raisers named by Pfc. Gagnon in the photograph including his own. Pfc. Hayes agreed with all of the identities named by Pfc. Gagnon except Sgt. Hansen, saying that Cpl. Block was at the base of the flagstaff. The Marine lieutenant colonel told Pfc. Hayes that the identities had already been made public and would not be changed and to not mention anything in public (that officer would later deny that Pfc. Hayes told him of the mis-identification).[3][12]

A Marine Corps investigation of the identities of the six second flag-raisers began in December 1946 and concluded in January 1947, confirming Pfc. Hayes' claim that Cpl. Block, not Sgt. Hansen, was in the photograph, and that no one party was responsible for the mis-identification.[3] The identities of the other five second flag-raisers were confirmed.

In June 2016, the Marine Corps review board announced that John Bradley had incorrectly been identified in the photograph.[8] The person initially ascribed to Bradley (fourth from left) was that of Sousley, while the person in Sousley's former position (second from left) was Harold Schultz.[8][3] The identities of the other five flag-raisers were confirmed. Schultz had never publicly mentioned that he was a flag-raiser or was in the photograph.[13][14]

A third Marine Corps investigation into the identities of the six second flag-raisers concluded in October 2019, that Keller was in the Rosenthal's photograph in place of Rene Gagnon (fifth from left).[15] Gagnon, who carried the larger second flag up Mount Suribachi, helped lower the first flagstaff and removed the first flag at the time the second flag was raised.[3] Photos and video footage showed that the person (Keller) who had been thought to have been Gagnon was wearing a wedding ring; at the time, Keller was married and Gagnon was not. The person (Keller) also did not have a facial mole; Gagnon did. The Marine Corps photo taken by Private Robert Campbell which showed both flags on top of Mount Suribachi verified that Keller was actually the person thought to have been Gagnon.[3] The identities of the other five flag raisers including Schultz were confirmed. Like Schultz, Keller never publicly mentioned that he was a flag-raiser or that he was in the photograph.

Notes

- "...Any unproved and malicious gossip about any member of our Marine Corps is a direct reflection on you as a member or former member of our Corps. Nothing is more malicious and indecent than the tearing down of characters and lives through the spreading of untruths..."

References

- Shooting Iwo Jima. Military History. Retrieved March 14, 2020 – via YouTube.

- "Warrior in iconic Iwo Jima flag-raising photo was misidentified, Marines Corps acknowledges". NBC News. 2019-10-16. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- Robertson, Breanne, ed. (2019). Investigating Iwo: The Flag Raisings in Myth, Memory, and Esprit de Corps (PDF). Quantico, Virginia: Marine Corps History Division. pp. 243, 312. ISBN 978-0-16-095331-6.

- "Joe Rosenthal and the flag-raising on Iwo Jima". The Pulitzer Prizes.

- "Meet the Marine the world just learned helped raise the flag at Iwo Jima in World War II". USA Today. 2019-10-22. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- Rural Florida Living. CBS Radio interview by Dan Pryor with flag raiser Ernest "Boots" Thomas on February 25, 1945 aboard the USS Eldorado (AGC-11): "Three of us actually raised the flag"

- The Man Who Carried the Flag on Iwo Jima, by G. Greeley Wells. New York Times, October 17, 1991, p. A 26

- USMC Statement on Marine Corps Flag Raisers, Office of U.S. Marine Corps Communication, 23 June 2016

- The Marine Corps War Memorial Marine Barracks Washington, D.C.

- "Memorial honoring Marines dedicated". Reading Eagle. Pennsylvania. Associated Press. November 10, 1954. p. 1.

- "Marine monument seen as symbol of hopes, dreams". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Washington. Associated Press. November 10, 1954. p. 2.

- Bradley, James. Flags of Our Fathers. p. 417.

- Jackie Mansky (June 23, 2016). "The Marines Have Confirmed That One of the Men in the Iconic Iwo Jima Photo Has Been Misidentified for 71 Years". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

2nd Paragraph, "the marine never publicly revealed his role"

- Jim Michaels (June 23, 2016). "Marines misidentified one man in iconic 1945 Iwo Jima photo". azcentral.com.

went through life without publicly revealing his role

- "Marines correct 74-year-old Iwo Jima error". NBC News.