Harold T. Pinkett

Harold Thomas Pinkett (April 7, 1914 – March 13, 2001)[1] was an African-American archivist and historian. In 1942, he became the first African-American archivist employed at the National Archives of the United States.[2] He was also the first African-American to become a fellow of the Society of American Archivists and to be editor of the journal The American Archivist. He was an expert in agricultural archives, and served as president of the Agricultural History Society.

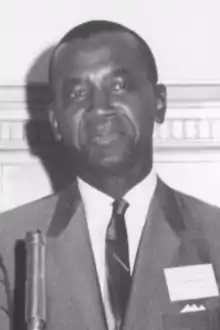

Harold T. Pinkett | |

|---|---|

Harold T. Pinkett, July 1969 | |

| Born | April 7, 1914 |

| Died | March 13, 2001 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Archivist |

Personal life

Ancestry

Pinkett's ancestors were free blacks in Maryland as early as 1820, including Pinkett's great-grandfather, Denard Pinkett.[2] Denard worked as a free laborer on a slaveowner's farm in Somerset County and later married one of his slaves, Mary, with whom he had twelve children. All twelve of these children were born slaves under a Maryland slave law that stated slave status came from the mother.[2] Adam Pinkett was one of Denard's children and was Harold T. Pinkett's grandfather.

Adam fought for the Union Army in the American Civil War from 1863 to 1866. After the war, he was fortunate to become literate and own both land and a house. He helped found his local Methodist Episcopal church and soon became licensed as a pastor.

Harold's father, Levin Wilson Pinkett, lacked a formal education and worked as a custodian and gardener.[2] Levin, like his father, Adam, advanced to become a pastor in the local Methodist Episcopal church.

Early life and education

Harold T. Pinkett was born on April 7, 1914, to Levin Wilson Pinkett and Catherine Pinkett. He was born in the segregated area of Salisbury ravaged by Jim Crow vigilantism. Between 1889 and 1918, whites committed seventeen lynchings and the area was named "Mississippi on the Chesapeake."[2] Throughout his life, he remained committed to education, religion, and personal achievement.

As a boy, Pinkett was a newsboy for the Afro-American and also distributed issues of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People's The Crisis. Pinkett later wrote for the publication.

When he was sixteen, Pinkett enrolled in Morgan College, a Methodist institution.[2] He was able to garner a Maryland state scholarship to pay for his tuition and he waited tables each summer to cover his rent. While at Morgan, he pledged to Omega Psi Phi, Zeta Sigma Pi and Alpha Kappa Mu. He graduated in 1935 with highest honors.[3]

Pinkett wanted to pursue a graduate education in history, but the University of Maryland was still segregated. So in the fall of 1935, Pinkett began his graduate work at the University of Pennsylvania.[2] He lived with family nearby to save money and also worked for the New Deal's National Youth Administration as a social investigator in the Public Defender's Office.[2]

After just one year, he began teaching Latin at a Baltimore high school, where he stayed for a year and a half. The experience gave him the ambition to return to the University of Pennsylvania to finish his master's degree in 1938.[2] However, he was struggling financially and after graduation, he returned south to teach at Livingstone College. He was appointed as a sabbatical fill-in for the 1938–1939 school year. After his appointment was over, he wanted to return to school for his doctorate. The University of Maryland remained closed to African Americans so he enrolled in Columbia University.

After just one year at Columbia, Pinkett began to struggle financially and turned to teaching again. From 1940 to 1941, he was a faculty member at Florida Normal and Technical Institute in St. Augustine and taught history, government and geography.[2]

In 1941, Pinkett returned to teach at Livingstone. He also began to court Lucille Cannady and they married in the spring of 1943. Lucille also worked with the federal government, working with the Department of Labor for 33 years.[2]

After the war, Pinkett returned to graduate school for his doctorate. In 1948, he began his work at American University.[2] He graduated in 1953 with a PhD in history and archival administration. His dissertation was entitled “Gifford Pinchot and the Early Conservation Movement in the United States," which went on to be published by the University of Illinois Press and won the Agricultural History Society's book of the year award in 1968.[2]

Career

1940s & WWII

In 1941, while he was still at Florida Normal College, Pinkett published his first article in the Journal of Negro History.[2] He also began reviewing books for the journal, often addressing race and ethnicity under the umbrella of American democracy.

But in the beginning of 1942, Pinkett was approached by the National Archives who were looking for someone with experience in Negro history. On April 16, 1942, Pinkett began his professional position with the National Archives, the first African American to be hired as a professional with the Archives.

As he began work with the Archives, he noticed that he was the only African American doing professional or clerical work: all other black workers were employed as laborers, messengers, custodians and elevator operators.[2] Not only that, but southerners dominated the Archives. He later referred to this as the "Era of the Confederate Archives."[2]

Only Dwight Hillis Wilson and Roland C. McConnell followed Pinkett into professional careers at the Archives, and they were both only there temporarily due to the war. (McConnell left the Archives in 1947 to teach at Morgan College and Wilson left in 1946 to work in Italy with the Allied Force Records Administration.)

While he was "a curiosity" at the Archives, his social life was strained with segregated restaurants and other areas that restricted his presence.[2]

In 1943, Pinkett applied for a position in the Division of Agriculture Archives and earned the position, beating out all the other white candidates. His strong work here garnered him a promotion as an archivist, which he held from 1942 to 1948.[2]

Also in 1943, Pinkett joined the Society of American Archivists, which had been established in 1936. Although the society was led by white men until the 1960s, he was named an SAA Fellow in 1962, elected to the SAA Council in 1971, and was appointed editor of the American Archivist from 1968 to 1971.[2]

However, that December, Pinkett got his draft notice. He was inducted on December 9 and served in Maryland, Massachusetts, France, Belgium, and Japan in teaching and administration positions.[2] He achieved the rank of technical sergeant in the army and earned the Good Conduct Medal, the American Theater Ribbon, the European, African, Middle Eastern Theater Ribbon, the Atlantic-Pacific Theater Ribbon, the Army Occupation Medal (Japan) and the World War II Victory Ribbon.[2]

While serving in the war, Pinkett struggled with the racism of the segregated army.[2] He tried to transfer units twice, being rejected both times. He also declined to be trained as an officer as he "had no wish to risk life and limb for a country that abrogated his civil rights."[2]

He also continued to write while in service, for both academia and popular consumption, on topics such as race, war, the media's portrayal of African Americans, segregation and history. Near the war's end, he wrote about his experiences, saying that "most Army Jim Crow is entirely unnecessary."[2]

1950s & 1960s

Pinkett left the army in 1946, continuing his work at the National Archives that June. He continued to write for several publications and was named supervisory archivist in 1948, where he stayed until 1959.[2] He also completed six inventories for the National Archives and continued to advocate for the research uses of oral history and film.

In his tenure at the Archives, he assisted scholars such as Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Merle Curti, Samuel P. Hays, Donald C. Swain, Roderick Nash, and James Harvey Young.[2]

In 1959, Pinkett applied for chief of the Agriculture and General Services Branch. He was the only black person among 25 candidates. He was promoted, but nevertheless believed it to be belated. From 1959 to 1962, Pinkett supervised the branch's archival and administrative operations.[2] He played a pivotal role in which records were kept and which were destroyed. His work in advising researchers and government officials earned him a Commendable Service Award in 1964.[2]

In 1968, after being passed over for other roles, Pinkett was promoted to Divisional Deputy Director. This is also when he took on editorial responsibilities with the American Archivist. From 1970 to 1972, Pinkett also served as a member on the editorial board of the new Prologue: Journal of the National Archives, as well as contributing articles.[2] In 1970, he served as co-director of the National Archives Conference on Research in the Administration of Public Policy to encourage the collaboration of archivists and historians.[2]

1970s & SAA

In 1971, Pinkett took on the leadership duties of the newly created Natural Resources Records Branch.[2] This transfer made him the highest-ranking African American in the General Services Administration.[2]

By the early 1970s, African American history was an incredibly popular area of study among academies and archives. The Civil Rights Movement continued to grow and Pinkett shared the goals of younger advocates, but with different means. Pinkett continued to write articles, edit and review journals and even present at conferences.

In addition to his participation in the Civil Rights Movement, he was also deeply involved with the Society of American Archivists. As Alex H. Poole explains, "many younger members viewed SAA as sexist, elitist and homogenous: they lobbied for diversity in the profession as well as in collections."[2]

Pinkett decided to run for Vice President of the SAA, although he lost by seventeen votes. But he still remained active with the SAA, serving on the Nominating Committee (1973–974), the Urban Archives Committee (as chair) (1975–1976), the Awards Committee (as chair) (1977–1978), and the American Historical Association–Organization of American Historians–SAA Joint Committee (1977–1980).[2] He also continued to write and review for several publications.

Also in the 1970s, Pinkett served on the Agricultural History Society's executive committee (1972–1975) and the editorial board (1977–1979). He also remained active in the Forest History Society, serving on its board of directors for two decades (1971–1991) and was elected president, serving from 1976 to 1978.[4] Pinkett was named a Fellow of the Forest History Society in 1975, the Society's highest honor.[5]

He also taught at Howard University from 1970 to 1976 and at American University from 1976 to 1977.[2]

At the end of the 1970s, Pinkett saw a decrease in professionalism and scholarly investment at the National Archives and chose to retire. He later received an Exceptional Service Award.[2] Pinkett later said he was "not bitter" about his lack of progression at the Archives, although he worked harder than non-black employees who received recognition and promotion. As fellow archivist Wilda Logan said, Pinkett “probably had to walk on water twice” to achieve his professional positions.[2]

1980s, 1990s & Retirement

Although he retired from the National Archives, he stayed involved in archival work. In 1980, he helped Howard University establish its University Archives and worked as an archival consultant for African American organizations such as the National Business League (1981, 1983), the United Negro College Fund (1982, 1984), the National Urban League (1982), The Links, Inc. (1986), and the NAACP (1986–1987).[2] He also worked with Cheyney University and contributed to The American Archivist and the American Library Association World Encyclopedia of Library and Information Services.[2]

He remained an integral member of the Agricultural Historical Society and served in the executive committee from 1983 to 1986.[2] He also presided over the society from 1982 to 1983. He wrote journal articles for the AHS journal, Agricultural History, and continued to write book reviews for several publications.

Pinkett worked as a consultant for many universities and institutions throughout his retirement, including Atlanta University and the Eugene and Agnes Meyer Foundation.

Legacy

Throughout his career, Pinkett fought for minority representation throughout the archival profession, especially in the SAA and the National Archives. He suggested that minorities serve on the Society's committees and boards, that they recruit minorities to projects and that they publicize the findings of their Task Force on Diversity.[2] Before the Task Force disbanded, they formed the Minorities Roundtable, later the Archivists and Archives of Color Roundtable.

In 1999, The Society of American Archivists award for minority graduate students was named after Pinkett.[6] He died on March 31, 2001, just shy of his 87th birthday.[7] He left open more doors for his predecessors than he had when he began archival work over 60 years earlier. Archivist Wilda Logan called him "the Martin Luther King, Jr. of archivists," and he is considered the father of African American archivists and archival work.[2]

References

- Helms, Douglas (2001). "Obituary: [Dr. Harold T. Pinkett]". Agricultural History. 75 (3): 349–351. doi:10.1525/ah.2001.75.3.349. JSTOR 3745135.

- Poole, Alex H. (2017-09-01). "Harold T. Pinkett and the Lonely Crusade of African American Archivists in the Twentieth Century". The American Archivist. 80 (2): 296–335. doi:10.17723/0360-9081-80.2.296. ISSN 0360-9081.

- "Harold Pinkett: An Archivist and Scholar". Pieces of History. 2016-02-18. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- Poole, Alexander (Spring–Fall 2018). "Biographical Portrait: Harold T. Pinkett (1914-2001)" (PDF). Forest History Today. pp. 47–58. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- "FHS Fellows". Forest History Society. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- "Harold T. Pinkett Minority Student Award". www2.archivists.org. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- Ligon (2014-06-17). "Dr. Harold T. Pinkett, The First African-American Archivist at the National Archives". Rediscovering Black History. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

External links

- Harold Pinkett Papers at the Moorland Spingarn Research Center, Howard University