Harry John Lawson

Henry John Lawson, also known as Harry Lawson,[1] (23 February 1852–12 July 1925) was a British bicycle designer, racing cyclist, motor industry pioneer, and fraudster. As part of his attempt to create and control a British motor industry Lawson formed and co floated The Daimler Motor Company Limited in London in 1896. It later began manufacture in Coventry. Lawson organised the 1896 Emancipation Day drive now commemorated annually by the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run on the same course.

Early years

Lawson was born on February 23, 1852, in the City of London the son of Thomas Lawson, a Calvinistic Methodist minister and brass turner and his wife Anne Lucy Kent.[2]

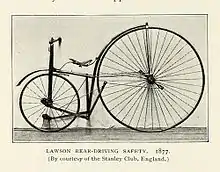

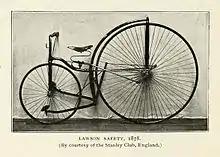

In 1873 the family moved to Brighton and Lawson designed several types of bicycle. His efforts were described as the "first authentic design of safety bicycle employing chain-drive to the rear wheel which was actually made" and has been ranked alongside John Kemp Starley as an inventor of the modern bicycle.[3][4][5]

In 1879 he married Elizabeth Olliver (b.1850) in Brighton. They went on to have four children, two sons and two daughters.[2]

In the early 1880s he moved to Coventry.

Motor promoter

Lawson saw great opportunities in the creation of a motor car industry in Britain and sought to enrich himself by garnering important patents and shell companies.

In 1895, as one of many attempts to promote his schemes and lobby Parliament for the elimination of the Red Flag Act, Lawson and Frederick Simms founded the Motor Car Club of Britain.

Lawson and the Motor Car Club organised the first London to Brighton car run, the "Emancipation Run", which was held on 14 November 1896 to celebrate the relaxation of the Locomotives Act 1865 (the Red Flag Act), which eased the way for the start of the development of the British motor industry.[6]

Lawson attempted to monopolise the British automobile industry through the acquisition of foreign patents. He acquired exclusive British rights to manufacture De Dion-Bouton and Bollée vehicles. He founded a succession of promotional companies including: The British Motor Syndicate — not to be confused with British Automobile Commercial Syndicate Limited. BMS was the first of many of Lawson's schemes to collapse in 1897. Lawson also founded British Motor Company, British Motor Traction Company, The Great Horseless Carriage Company, Motor Manufacturing Company, and with E. J. Pennington forming Anglo-American Rapid Vehicle Company. With his one great success, The Daimler Motor Company Limited, he bought in the rights of Gottlieb Daimler though this company too was to be reorganised in 1904. After a succession of business failures, British Motor Syndicate was reorganised and renamed British Motor Traction Company in 1901, led by Selwyn F. Edge.

Legal problems

Many of Lawson's patents were not as defining as he had hoped, and from 1901 a series of legal cases saw the value in his holdings eroded. Lawson's patent rights were subsequently eroded through successful lawsuits by Automobile Mutual Protective Association. In 1904 Lawson, along with Ernest Terah Hooley, was tried in court for fraudulently obtaining money from his shareholders and, after representing himself in court, he was found guilty and sentenced to one year's hard labour.[7]

Lawson was completely out of the automobile industry by 1908[8] and disappeared from the public gaze for some years.

He reappeared as a director of Blériot Manufacturing Aircraft Company Ltd., the English branch of Louis Blériot's aircraft company. Lawson secretly acquired control of the company just before a public subscription to help expand its wartime effort in the First World War but the company soon found itself in breach of its contract with Blériot. When this came to light, the company was wound up and its director found guilty of fraud and dishonesty.[9]

Lawson survived being torpedoed on the ferry "Sussex" crossing the English Channel in March 1916.[10]

He retired from the public gaze and died at his home in Harrow, London on 12 July 1925 aged 73.[10] After Lawson's death, Herbert Osbaldeston Duncan, former Commercial Manager of his British Motor Syndicate, described him thus:

"He was neither a greedy man nor an egoist. On the contrary he was always fair and extremely generous. He paid largely and was most liberal in the golden days of his success. A cheque was always ready to be handed over with a kindly smile to friends who assisted him with his dealings or company-promoting schemes. Lawson was a clever man. Perhaps his greatest misfortune was in not being supported properly in his business by others equally intelligent." (Duncan, Herbert Osbaldeston The World on Wheels, thrilling true tales of the Cycle & Automobile Industry, vol 2. Self-published, 1926)

See also

References

Notes

- 'Henry John Lawson' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- "Grace's Guide to British Industrial History". Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- Storey, Richard (2004). Lawson, Henry John (1852–1925).

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Lawson's 'Bicyclette', 1879". The Science Museum. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

Patented by Henry Lawson in 1879, this bicycle represents the first step in the evolution of the modern safety cycle. Although like the ordinary or penny-farthing bicycle, the front wheel remained larger than the rear, the difference in size was not so exaggerated, making it lower, and therefore safer than its forerunner. Lawson's Bicyclette also featured the innovation of a chain drive to the rear wheel.

- Tony Hadland and Hans-Erhard Lessing (2014). Bicycle Design, An Illustrated History. MIT Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-262-02675-8.

Lawson's 1879 Bicyclette.

- Setright, L. J. K. (2004). Drive On!: A Social History of the Motor Car. Granta Books. ISBN 1-86207-698-7.

- "Central Criminal Court, Dec. 17. The Hooley-Lawson Case: Verdict". The Times. 19 December 1904.

- James J. Flink. The Automobile Age. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1988. p. 22.

- "Winding Up Of An Aircraft Company., In Re Bleriot Manufacturing Aircraft Company (Limited)". The Times. 20 January 1916.

- Burgess-Wise, David (2006). Brighton Belles. Marlborough UK: Crowood Press. ISBN 1-86126-764-9.

Bibliography

- Flink, James J. (1988), The Automobile Age, MIT Press

Further reading

- Saul, S. B. (December 1962), "The Motor Industry in Britain to 1914", Business History, 5 (5): 22–38, doi:10.1080/00076796200000003