Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum

The Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum is the presidential library and resting place of Harry S. Truman, the 33rd president of the United States (1945–1953), his wife Bess and daughter Margaret, and is located on U.S. Highway 24 in Independence, Missouri. It was the first presidential library to be created under the provisions of the 1955 Presidential Libraries Act, and is one of thirteen presidential libraries administered by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

| Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

Interactive map showing the location of Truman Presidential Library | |

| General information | |

| Location | 500 West U.S. Highway 24 Independence, Missouri, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 39°06′12″N 94°25′15″W |

| Named for | Harry S Truman |

| Inaugurated | Dedicated on July 6, 1957 |

| Cost | $1,700,000 |

| Management | NARA |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Edward Neild (primary), Gentry and Voskamp |

| Website | |

| https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/ | |

History

Built on a hill overlooking the Kansas City skyline, on land donated by the City of Independence, the Truman Library was dedicated July 6, 1957. The ceremony included the Masonic Rites of Dedication and attendance by former President Herbert Hoover (then the only living former president other than President Truman), Chief Justice Earl Warren, and former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.[1]

Here, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Medicare Act on July 30, 1965.

The museum has been victimized by significant burglaries twice.

John Wesley Snyder, Truman's Treasury Secretary and close friend, donated his personal collection of 450 rare coins to the museum in March 1962. That November, burglars stole the entire collection. None of the stolen coins have been recovered. Snyder helped coordinate an effort among 147 coin collectors to reconstruct the collection, which went back on display in 1967, at a ceremony attended by Truman.[2]

While serving as president, Truman had received gifts of jewel encrusted swords and daggers from Saud of Saudi Arabia, then the crown prince, and Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran. He turned these items over to the National Archives and Records Administration as required by law, and they were displayed at the museum. According to the museum curator, they "had embedded diamonds and rubies and sapphires, a number of precious stones in their hilts and in their scabbards".[3] In March 1978, burglars broached the front door of the museum, smashed showcases, and stole the three swords and two daggers, which were valued at US$1 million at that time. None of the stolen items have been recovered. In 2021, the FBI offered a reward of up to $1 million for return of the items.[3]

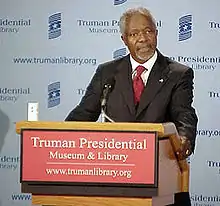

On December 11, 2006, Kofi Annan gave his final speech as Secretary-General of the United Nations at the library, where he encouraged the United States to return to the multilateralist policies of Truman.

Design

The lead architect of the project was Edward F. Neild of Shreveport, Louisiana. Truman had picked Neild in the 1930s, during his time as presiding judge of Jackson County, to design the renovation of the old county courthouse in Independence and to oversee the construction of the new courthouse in Kansas City, after being favorably impressed by Neild's work on the courthouse in his native Caddo Parish.[4][5] Neild was also one of the architects involved in the reconstruction of the White House during Truman's presidency.

Neild died July 6, 1955, at the Kansas City Club while working on the design.[6] The work was completed by Alonzo H. Gentry of Gentry and Voskamp, the firm that designed Kansas City's Municipal Auditorium.[7][8]

Truman had initially wanted the building to resemble his maternal grandfather Solomon Young's house in Grandview, Missouri.[9]

In response to a New York Times review that recalled Frank Lloyd Wright influences in the library's horizontal design, Truman was reported to have said, "It's got too much of that fellow in it to suit me."[9]

Architects Gould Evans designed a $23 million renovation of the entire facility, unveiled in 2001.[10] The changes included the extensive use of glass in the relatively windowless structure and a significant change to the space between Truman's grave and the museum.[11]

Truman's activities on the premises

Truman actively participated in the day-to-day operation of the Library, personally training museum docents and conducting impromptu "press conferences" for visiting school students. He frequently arrived before the staff and would often answer the phone to give directions and answer questions, telling surprised callers that he was the "man himself."

His visitors included incumbent Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, former President Hoover, Jack Benny, Ginger Rogers, Robert F. Kennedy, Thomas Hart Benton, and Dean Acheson.

Truman's office

When Truman left the White House in 1953, he established an office in Room 1107 of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City at 925 Grand Avenue. When the library opened in 1957, he transferred his office to the facility and often worked there five or six days a week.[12] In the office, he wrote articles, letters, and his book Mr. Citizen.

In 2007, the Truman Library Institute announced a $1.6 million preservation and restoration of his working office to preserve the artifacts it contains and allow for easier public viewing.[13] The three-stage project completed in 2009 and features an enclosed limestone pavilion for better access and viewing and an updated climate control system. The office appears today just as it did when Harry Truman died on December 26, 1972.[14]

Long a favorite of museum visitors, the office was viewed through a window from the library's courtyard. The pavilion will also allow for an interpretive exhibit describing the office.[13]

Truman's funeral services

Funeral services for Truman were held in the Library auditorium and burial was in the courtyard. His wife, Bess Truman, was buried at his side in 1982. Their daughter, Margaret Truman Daniel, was a longtime member of the Truman Library Institute's board of directors. After her death in January 2008, Margaret's cremated remains and those of her late husband, Clifton Daniel (who died in 2000), were also interred in the Library's courtyard. The president's grandson, Clifton Truman Daniel, is currently honorary co-chair of the institute's board of directors.

Exhibits and program

Two floors of exhibits show his life and presidency through photographs, documents, artifacts, memorabilia, film clips and a film about Truman's life.

The library's replica of the Oval Office is a feature that has been copied by the Johnson, Ford, Carter, Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Clinton, and George W. Bush libraries.

In an educational program called The White House Decision Center, school students take on the roles of President Truman and his advisors facing real-life historical decisions in a recreation of the West Wing of the White House.

Art

The mural Independence and the Opening of the West by Thomas Hart Benton adorns the walls of the lobby entrance. The mural, completed in 1961, was painted on site by Benton over a three-year span.

Visitors

Visitors after 1972 include incumbent Presidents Ford, Carter, and Clinton and Presidential Nominees John Kerry and John McCain.

References

- Dedication. Warren, Hoover, Hail New Truman Library, 1957/07/08 (1957). Universal Newsreel. 1957. Retrieved 2012-02-22.

- Bozarth, Victor (January 18, 2022). "The Truman Library Snyder Coin Collection Robbery and Other Recollections". CoinWeek. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- Reid, Cat; McCormick, Lisa (May 6, 2021). "Mystery at the museum: Inside the hunt for Truman's treasures". KSHB. Kansas City, Missouri. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- "Jackson County Courthouse". University of Missouri Extension. May 1981. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- "Historic Courthouse". Parish of Caddo. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- "Edward F. Nield, Sr". The New York Times. 7 July 1955. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- "Alonzo H. Gentry, Architect, Is Dead". Kansas City Times. February 7, 1967.

- Mertens, Randy (January 2012). "A Concrete Pedigree: A bit of Boss Tom's history lives in the Ag Building". CAFNR News. University of Missouri College of Agriculture, Food & Natural Resources. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- Burnes, Brian (November 2003). Harry S Truman: His Life and Times. Kansas City Star Books. ISBN 0-9740009-3-0. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- "GouldEvans". GouldEvans. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- "Renovation Information". Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- "Truman Places: Federal Reserve Building". Trumanlibrary.org. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- "Truman Library Receives $125,000 Save America's Treasures Grant to Preserve Truman's Working Office" (Press release). Truman Library and Museum. January 24, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- "Preservation of Harry Truman's Office at the Truman Library". Truman Library and Museum. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

Further reading

- McCray, Suzanne, and Tara Yglesias, eds. Wild about Harry: Everything You Have Ever Wanted to Know about the Truman Scholarship (University of Arkansas Press, 2021), how to work at this Library. online

External links

- Official website

- Newsreel clip of dedication of Truman Library, from the Internet Archive

- Harry Truman and Independence, Missouri: "This is Where I Belong", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- "Life Portrait of Harry S. Truman", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, broadcast from the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum, October 18, 1999

.jpg.webp)