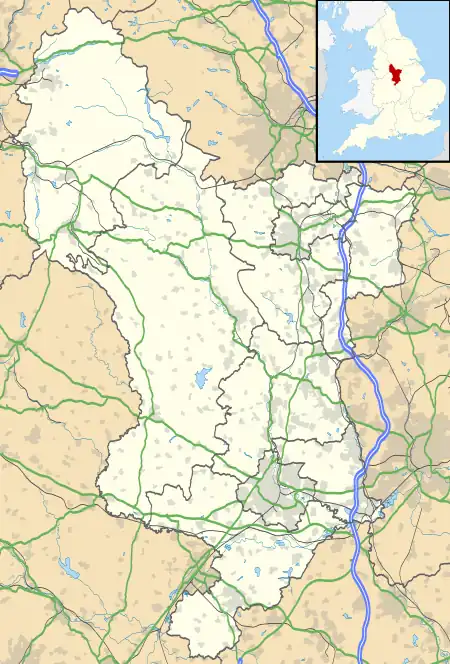

Hartington Middle Quarter

Hartington Middle Quarter is a civil parish within the Derbyshire Dales district, which is in the county of Derbyshire, England. Formerly a part of Hartington parish, for which it is named, it has a mix of a number of villages and hamlets amongst a mainly rural and undulating landscape, and is wholly within the Peak District National Park. It had a population of 379 residents in 2011.[1] The parish is 130 miles (210 km) north west of London, 20 miles (32 km) north west of the county city of Derby, and 5 miles (8.0 km) south east of the nearest market town of Buxton. Being on the edge of the county border, it shares a boundary with the parishes of Chelmorton, Flagg, Hartington Town Quarter, Hartington Upper Quarter, Middleton and Smerrill, Monyash in Derbyshire, as well as Hollinsclough, Longnor and Sheen in Staffordshire.[2]

| Hartington Middle Quarter | |

|---|---|

| Civil parish | |

| |

Hartington Middle Quarter Location within Derbyshire | |

| Area | 6.99 sq mi (18.1 km2) [1] |

| Population | 379 (2011) [1] |

| • Density | 54/sq mi (21/km2) |

| OS grid reference | SK 108658 |

| • London | 130 mi (210 km) SE |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Settlements |

|

| Post town | BUXTON |

| Postcode district | SK17 |

| Dialling code | 01298 |

| Police | Derbyshire |

| Fire | Derbyshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | hartingtonmiddlequarter-pc |

Geography

Location

Hartington Middle Quarter parish is surrounded by the following local locations:[2]

- Buxton, Chelmorton and Sterndale Moor to the north

- Hartington and Pilsbury to the south

- Flagg and Monyash to the east

- Hollinsclough and Longnor in Staffordshire to the west.

It is 6.99 square miles (18.1 km2; 1,810 ha) in area, 7+1⁄2 miles (12.1 km) in length and 2 miles (3.2 km) in width, within the north western portion of the Derbyshire Dales district as well as its most westerly parish, and is to the west of the county. The parish is roughly bounded by land features such as Earl Sterndale and Pomeroy settlements to the north, the River Dove to the west, the A515 road to the east, with Crowdecote, High Peak trail and Parsley Hay in the south.

Settlements and routes

There are a number of villages and hamlets within the parish:

- Earl Sterndale, the largest settlement, is roughly to the central north of the area. It has a two-row road layout, with many of the residences aligned to this.

From Earl Sterndale:

- Crowdecote is in the south of the parish, 1+1⁄3 miles (2.1 km) south east of Earl Sterndale

- Glutton is 1⁄3 mile (0.54 km) to the west

- Glutton Bridge is 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) to the south west

- High Needham is 1+2⁄3 miles (2.7 km) south east

- Hurdlow is to the east, 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) east

- Parsley Hay is 4 miles (6.4 km) south east

- Pomeroy is 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) east

- Sparklow is 2+1⁄3 miles (3.8 km) south east

Outside of these settlements, the parish is predominantly an agricultural and rural area. There are two key routes through the parish:

- The A515 road between Buxton and Ashbourne runs through Pomeroy and Parsley Hay. It forms much of the eastern perimeter of the parish

- The B5053 road spurs off the A515, and passes to the west of Earl Sterndale, through Glutton and Glutton Bridge which is over the River Dove, before entering Staffordshire.

Landscape

It is primarily farming and pasture land throughout the parish outside the populated areas. The region is feature rich with many hills and slopes, notable points of interest including High Edge, Chrome Hill and Parkhouse Hill (informally known as the Dragon's Back from their rugged appearance),[3] Hitter Hill, High Wheeldon, Dowel and Fox Hole caves, a number of tumulus, and Aldery Cliff by Earl Sterndale, these together culminating in scenic vistas as part of the wider Peak District characterisation.

Geology

Being within the Peak District National Park, much of the parish is of the Bee Low Limestones Formation. This is sedimentary bedrock formed approximately 331 to 337 million years ago in the Carboniferous period. Along the banks of the River Dove, comprises the Bowland Shale Formation which are mudstone, siltstone and sandstone deposits, formed approximately 319 to 337 million years ago in the Carboniferous period. Chrome and Parkhouse hills are remnants of apron reefs when water levels were higher.[4]

Water features

The parish, district and county western edge is formed by the River Dove. There are a few tributaries that start from springs on higher ground, including the Swallow Brook which shapes a north western perimeter of the parish.

Land elevation

The parish has a large range of hills and dales, with the lowest points surrounding the River Dove to the south west, from 245 metres (804 ft). Crowdecote, lying along the banks is slightly higher at 250–255 metres (820–837 ft), Earl Sterndale sits on the edge of a valley between 325–350 metres (1,066–1,148 ft), Parsley Hay at 335 metres (1,099 ft), Hurdlow is 355–370 metres (1,165–1,214 ft) and Pomeroy 375–380 metres (1,230–1,247 ft). The highest point is within the High Edge range to the far north, by a cairn, at 455 metres (1,493 ft). Other notable high peaks include Chrome Hill at 425 metres (1,394 ft), High Wheeldon (422 metres (1,385 ft)), Pilsbury Hill (395 metres (1,296 ft) and Parkhouse Hill (360 metres (1,180 ft)).

History

Toponymy

The name Hartington possibly derived from an Anglo Saxon farmer Heorta in the 6th century,[5][6] and later became Hortedun when recorded in the 1086 Domesday survey. It was in medieval times an extensive parish, and was divided into four townships, with Hartington Middle Quarter centred on Earl Sterndale, becoming a church parish and later a standalone civil parish in 1873.[7]

Parish and environment

The area is rich in historical remains, prehistoric examples including caves with occupational evidence dating from 500000BC such as at Etches near Dowel farm[8] and from 40000BC at Fox Hole.[9] There are several Middle or Late Neolithic period (4000 BC to 2351 BC) and Bronze Age (2350 BC to 701 BC) finds such as a stone axe within High Needham farm,[10] a flint axe at Parsley Hay[11] a bronze axe from Chrome Hill,[12] and an arrowhead[13] with several being placed in Buxton Museum. There are some barrows and cairns throughout the area typically dating from the Bronze Era, such as at Hindlow,[14] close to High Edge,[15] and at Glutton Hill,[16] although a number of others have since been destroyed by later mining and quarrying.[17][18] An iron knife was found in one of the excavated mounds, with a second burial dated approximately between the 1st to 7th century AD.[19] Later evidence during the Roman Britain occupation period (43 AD to 409 AD) include a possible settlement in Dowel Dale,[20] and a road from Derby to Buxton which ran in the east of the parish by Parsley Hay, which was close to and parallel to the present day A515 road.[21]

The Middle Quarter area was a part of the wider Hartington parish and manor, which was reported in 1066 at the time of the Norman invasion by William the Conqueror as under the ownership of Godwin of Tissington[22] and Ligulf. Another place, Soham or Salham had also been recorded in Domesday, and was thought to have been in the vicinity of Earl Sterndale.[23] Both were described as 'waste' with no value. By the time of the survey both manors had been granted to Henry de Ferrers as part of the wider Derbyshire holdings under the Honour of Duffield.[24] There were subsequent improvements by the Ferrers to the manors such that in 1204 a market and fair had been allowed to take place at Hartington, being one of the first in Derbyshire.[25] Also, there was growth throughout the outlying area; in 1244 on public record was details of the surrounding hamlets that had since sprung up, in what would become the Middle Quarter were listed Stenredile (Earl Sterndale),[26] Crudecote (Crowdecote),[27] Salvin (Salham), Nedham (High Needham),[28][29] and Hordlawe (Hurdlow).[30] Others mentioned at the same time included nearby Buckstanes (Buxton).

The same records also outlined an area around the 'forest of Hertingdone and Crudecotes up to the water of Goyt' which was not a true forested area, but a hunting area used by the earls called the Frith,[31] and adjacent to the royal Forest of High Peak. The manor and settlements were held by descendants until 1266 when Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby rebelled against Henry III and, after a defeat at the Battle of Chesterfield, lost his lands and titles. The ownership was granted to Edmund Crouchback, royal prince and Earl of Lancaster. In 1399 the manor was merged back into wider Crown holdings. In 1603 it was given to Sir George Hume but on his death in 1611 the holdings reverted to James I, who requested in 1614 a survey of the manor and the landholdings by William Heyward, including Earl Sterndale. In 1617 Hartington was again granted away, this time to George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham. In 1663, William Cavendish, Earl of Devonshire bought the manor which was held by his descendants until the 20th century.[32][33]

The Hartington parish was a sprawling area covering some 24,000 acres and one of the largest in the country, spanning some 16 miles (26 km) in length, and up to 5 miles (8.0 km) in width.[34] It was split into townships by the 16th century for easier administration,[33] or with the establishment of St Michaels chapel in around the 14th century.[35] It was described by the Parliamentary Survey of Livings, undertaken in 1650, reporting on Hartington and particularly the Middle Quarter: "It is a parish and vicarage of large extent, usually divided into four quarters. The two neather quarters are thought fitt to be continued to ye parish churche. The whole vicarage is worth £19 10s., whereof £10 aryseth out of the gleabe and the two neather quarters. Earl Sterndall is a chapel of ease in the parish of Hartington, a member of the middle quarter, which is thought fitt to be made a parish church, and these hamletts of middle quarter, Harlee, Glutton, Doewall, Crowdicoate, Wheeldontrees, Needham Graunge, Hurdlow, Cronkston, and Sterndale, £2."[36] It is thought that Hurdlow and Needham were more substantial settlements which shrunk in later medieval times and the areas repurposed for farming.[37][29] A formal civil parish was created for the Middle Quarter in 1873.[7]

There is a reputed story that Bonnie Prince Charlie's men came across cattle owned by Cronkstone Grange hidden in a dale, killing them and having a great feast contributing in the process to the name Glutton to the grange,[38] the placename predates those events, being Glotonhous in the 15th century.[39] Abbot's Grove is to the south of Earl Sterndale, it was built atop an earlier residence used by abbots when they were visiting monastery granges, During the 1850s, it was also the location of the local tannery.[38] Nat Gould, the prolific Victorian writer, was descended from the Wheeldon families who in the 16th-17th centuries resided at Cronkstone Grange, and Gould families who lived in Crowdecote[40] and for some centuries at Pilsbury Grange in neighbouring Hartington Town Quarter.[41][42] Hartington Middle Quarter held a workhouse in the 18th century housing 70 inmates, but the management was taken over by Bakewell poor law union in 1834 and a purpose built site erected in Bakewell.[43] A school was built in the grounds of the St Michael's chapel in 1850, while the Wesleyan church was also built in the same year.[38]

During the middle 1800s, the parish was involved in legal dispute, which set a judgement used in future law cases regarding issue estoppel, where the facts decided by an issue during a case cannot be litigated a second time between the same parties. It involved a Levershulme (then in Lancashire) family, the Goulds. In February 1848 a parent, Esther Gould had been moved to a Lancashire asylum, and in October 1849 there was an attempt to formally resettle her two children to Hartington Middle Quarter, where their father and her husband resided. The overseers, Bakewell poor law union notified Chorlton Poor Law Union that the father was actually a resident of Hartington Town Quarter due to it being his place of birth, which was under Ashbourne poor law union and so should have liaised with that authority, however the children were allowed to remain in Middle Quarter. In March 1854 while attempting to recover maintenance expenses for Gould, Chorlton appealed to the courts to determine Gould's last residence, which ascertained the last legal settlement of Gould was in Hartington Middle Quarter due to the location of her family, and thereby ordering Bakewell union to cover costs. Hartington Middle Quarter parish appealed against this order citing the earlier decision, which meant that Chorlton Poor Union was barred from disputing the order.[44][45]

To serve as a memory to those from the parish who served in the World War I conflict but did not return, a village hall was built using local contributions at Pomeroy in 1921. It was used for various local functions, celebrations and held regular Sunday School sessions regularly until the 1980s. It then fell into disuse, instead becoming a storage location for kit used by a local drama society.[46] A trio of pillbox defences were built during World War II in the High Edge and surrounding area, with two of those within the parish, and installed close to or atop cairns which were affected by their construction.[47][48] A German raid on an ammunition dump in Harpur Hill near Buxton in January 1941 was conducted over a wider area, with the bombs falling into the north of the parish and Earl Sterndale area. Although much fell into open countryside, some of those struck barns and outbuildings. The St Michaels' church at Earl Sterndale was also hit, but the registers and communion plate were saved before it burnt down completely, giving it the unenviable distinction of being the only church in Derbyshire destroyed during World War II. It was rebuilt in 1952.[49][50] Earl Sterndale suffered badly in the aftermath of the 1947 winter, becoming cut off from the wider country for seven weeks by the snow drifts.[50] Wheeldon Trees Farm was one of Derbyshire's most expensive properties sold in 2021, at a price of over £1.5 million.[51]

Industry

Although it's unknown how the Hartington and Soham manors were used from an agricultural perspective during prehistoric times to after the Romans, by the time of Domesday were considered to be little more than waste. There were enhancements by the Ferrers to the manors except for the hunting area in the north, but also due to Robert de Ferrers, 2nd Earl of Derby being a great benefactor, founding Merevale Abbey, Warwickshire in 1148 for the Cistercian monks, and endowing it with land grants from his estates in Hartington, where there was much unused land. In the Middle Quarter, Merevale was given land at Cronkston and Pilsbury for the establishment of granges, while at Cotefield another was established by Combermere Abbey in Cheshire.[52] These helped establishing villages such as Earl Sterndale which was only first recorded in 1244, so that labour to tend to the land was nearby and readily available.

Open field methods of farming was more commonplace around Hartington and Earl Sterndale, where arable land was rented out in strips to villeins, who in turn paid rent, fines for breaches in field maintenance, and rendered certain labour services to the lord of the manor. Some arable land was held in demesne, being farmed directly by servants of the lord. Demesne farming included the rearing of sheep, mainly for wool, but over time pastoral farming was more productive than arable. The Cistercians were particularly adept at taking advantage of the trade in selling wool once it became more in demand from the continent in the 13th century, exporting it via ports such as Huil in East Riding of Yorkshire. Later risks in supply, and labour shortages from the Black Death caused the monks to begin leasing their lands to tenants, which continued until the Dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century.

Lead mining was known in the wider area since at least Roman Britain times, with later records of a grant from William de Ferrers in 1171 to lands surrounding Cotefield Grange, along with a lead mine which was described as old even in that charter. A resurgence of activities took place in the 17th century throughout Hartington parish, much of the output was in the Upper Quarter area near Buxton, but the Middle Quarter also had some mining on a smaller scale, with pits in the Frith, Upper Edge, Chrome Hill, Earl Sterndale, High Needham, Crowdecote, Wheeldon Trees, Cronkstone and Parsley Hay,[4] and of which was mainly worked out by the 19th century. Limestone is abundant, particularly in the High Edge area, and was extensively mined for building as well being converted into lime.[53]

Corn milling was recorded locally; it was first mentioned in Duchy of Lancaster accounts of 1434-1435 when a mill on the River Dove at Crowdecote was granted to John Pole on a ten year lease. The mill was leased by ancestors of Nat Gould in the 17th century,[40] and remained in use beyond enclosure activities of 1800, but had become disused by the early 20th century. The site was partly in use beyond the mill's demise, with the mill race being used as a sheepwash. North and west of the location of the drying oven has for many years been used as a refuse site and has also subject to mechanised ground tilling during the 20th and 21th centuries. Areas of excavation were undertaken, with unknown structural remains being identified along with a corn drying kiln. A stone-flagged floor of limestone from an unknown date, possibly remains of a yard, was found. Dry stone walls, possibly relating to the aforementioned sheepwash, were also discovered.[54]

With the widespread rearing of cattle, in the 1870s a creamery was opened in Glutton to process the output of this produce. The factory was close to Glutton Bridge, southwest of Hitter Hill. It became well known for its dairy products, particularly Wensleydale cheese for Express Dairies. The facility closed in the 1960s.[55] Local occupations recorded in early 19th century censuses included a tannery at Abbot's Grove in Earl Sterndale,[38] also there was a bakery and baker's shop,[50] and post office and up to four public houses, with travelling salesmen providing a number of products such as tools and hardware, clothing and butchery. There was also a blacksmith in Earl Sterndale and Crowdecote.[50][56]

Former railways and stations

The Cromford and High Peak Railway was built through the area, reaching Hurdlow in 1830. Two stations were opened for handling goods, Parsley Hay and Hurdlow both in 1833, and eventually catering to passengers from 1833 until 1877. The Ashbourne Line was joined to this, just south of Parsley Hay in 1899. Traffic – by this time almost exclusively from local quarries, with a handful of day trip excursions – was slowly decreasing during the Beeching era, and the first section of the line was closed in 1963. The rest of the line was fully closed in spring 1967 with the portion of the line within the parish converted into the High Peak Trail, and the station locations becoming stop-off points for the walking route.[57]

Governance and demography

Population

There are 379 residents recorded within the parish for the 2011 census,[1] an increase from 362 (5%) of the 2001 census. The population majority is mainly middle aged and older, with the 18-64 years age bracket taking up 60%. Infants to teenage years are another sizeable grouping of around 24%, with elderly residents (65 years and older) making up a small number (16%) of the parish population.[58]

Labour market

A substantial number of 18 years old locals and above are in some way performing regular work, with 68% classed as economically active. 15% are economically inactive, and 17% are reported as retired. A majority of residents' occupations are in skilled trades, professional, elementary and plant and machine operatives.[58]

Housing

Over 150 residences exist throughout the parish, primarily at Earl Sterndale, the largest settlement. The majority of housing stock is of the fully detached type, with other substantial formats including semi detached or terraced. The vast majority of these (>100) are owner occupied, with other tenure including social and private rentals.[58]

Mobility

The majority of households (>90%) report having the use of a car or van, which is expected with a relatively isolated area with few amenities.[58]

Local bodies

Hartington Middle Quarter parish is managed at the first level of public administration through a parish council.[59]

At district level, the wider area is overseen by Derbyshire Dales district council. Derbyshire County Council provides the highest level strategic services locally.

Community and leisure

Amenities

Bed and breakfast facilities exist throughout the parish at various farms, outbuildings and public houses, catering particularly to tourists visiting the national park.[58]

There are camping sites at Crowdecote and Pomeroy, which also has a caravan site.

Public houses exist at Crowdecote, Earl Sterndale and Sparklow. There is a site at Pomeroy, but it is within the portion of the settlement that is in the parish of Chelmorton.

Car parks accessible by the public are at Parsley Hay and Hurdlow.

The parish has few facilities otherwise; shopping for some basic everyday items generally requires travelling to Longnor, Hartington or Buxton.

Recreation

The medium distance Peak District walking route Tissington Trail follows the now unused Ashbourne railway line, which routes from north to south within the parish.

Route 68 of the National Cycle Network (NCN) overlays this trail and continues via Earl Sterndale to Buxton and beyond.

NCN Route 54 meets the trail in the very south of the parish, overlain by the High Peak Trail which ends just outside the parish by Dowlow.

NCN Route 548 comes from Hartington and meets the High Peak Trail.

The National Park Authority operates cycle hire facilities at Parsley Hay.

The Pennine Bridleway also overlays the High Peak trail.

Aldery Cliff, south of Earl Sterndale, offers abseiling opportunities.[60]

There is a cricket field in the parish.[58]

Education

There is a school at Earl Sterndale village adjacent to the church, Earl Sterndale CofE Primary.[62]

Landmarks

Listed buildings

There are 14 listed buildings of architectural merit throughout the parish with statutory listed status at Grade II,[63] including the 19th-century Church of St Michael in Earl Sterndale.[64]

National park

The parish is wholly contained within the Peak District national park.

War memorials

A monument is at Earl Sterndale church graveyard, commemorating locals who served in both World War I and WWII conflicts.[65]

There is a village hall built at Pomeroy village in 1921 commemorating locals who served in but did not return from the World War I conflict.[66]

Religious sites

St Michael and All Angels in Earl Sterndale is an Anglican place of worship which dates from the 14th century but was rebuilt in the mid-19th century.[67] There is also a Methodist church in Earl Sterndale.[68]

Notable people

- Roy Fisher (1930–2017), English poet and jazz pianist

References

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Hartington Middle Quarter parish (E04002761)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics.

- "Hartington Middle Quarter". Ordnance Survey.

- "Walk: Parkhouse Hill and Chrome Hill, Derbyshire". Countryfile.com. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- Heathcote, C (Summer 2012). "A HISTORY AND GAZETTEER OF THE LEAD MINES WITHIN HARTINGTON LIBERTY, DERBYSHIRE: 1191 - 1890". Mining History: The Bulletin of the Peak District Mines Historical Society. Vol. 18, no. 3. Peak District Mines Historical Society. pp. 23, 28–34.

- "Hartington :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "Hartington Neighbourhood Plan" (PDF).

- GENUKI. "Genuki". www.genuki.org.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR112 - Etches' Cave, north-west of Dowal Hall farm, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR119 - Fox Hole Cave, north-east of Green Lane Cottage, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR13227 - Neolithic axe head, High Needham Farm, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR1445 - Flint axe and flakes, Parsley Hay, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR135 - Bronze Axe, Chrome Hill, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR1453 - Barbed and Tanged Arrowhead, Waggon Low, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR117 - Round barrow (site of), (3 of 4), Hindlow, Hartington Upper Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR71 - Cairn and Type FW3/23 Pillbox, New High Edge Raceway, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR90 - Round barrow, Glutton Hill, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR114 - Anglian round barrow (lost, approximate site of), Earl Sterndale, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR84 - Brier Low barrow (site of), Hartington Upper Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR1435 - Bowl Barrow, Pilsbury, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR98 - Possible Romano-British Settlement, Dowel Dale, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MDR1230 - Roman Road, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "Godwin". Open Domesday Book. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "Soham". Open Domesday Book. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "Hartington". Open Domesday Book. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- Samantha Letters (18 June 2003). "Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs to 1516: Derbyshire". archives.history.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "Earl Sterndale :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "Crowdecote :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "High Needham :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "MDR1223 - Possible Shrunken medieval village, High Needham (Needham Grange) - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- "Hurdlow Town :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "The Frith :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "The following information includes the entire trawl for historic references pertaining to Pilsbury Castle which was undertaken as part of thePilsbury Castle Archaeological Survey 2001-2002". studylib.net. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Weston, Ron (2000). Hartington: A Landscape History from the earliest times to 1800. Derbyshire County Council - Libraries and Heritage Department. ISBN 0-903463-58-X.

- "Home Page". Hartington Church. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- "The Andrews Pages : Earl Sterndale, Derbyshire: Kelly's Directory, 1891". www.andrewsgen.com. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- "Churches of Derbyshire: The Chapelry of Hartington, J. Charles Cox, 1877". places.wishful-thinking.org.uk. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- "MDR1226 - Shrunken medieval settlement, Hurdlow Town, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- The Derbyshire Village Book. Derbyshire Federation of Women's Institutes & Countryside Books. 1991. ISBN 1-85306-133-6.

- "Glutton :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- "William Gould 1655-1725". Nat Gould. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- "John Wheeldon 1709-1780". Nat Gould. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- "Nat Gould". Nat Gould. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- "The Workhouse in Bakewell, Derbyshire". www.workhouses.org.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- Bench, Great Britain Court of King's; Ellis, Thomas Flower; Blackburn, Colin Blackburn Baron; Chamber, Great Britain Court of Exchequer (1856). Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Queen's Bench: And the Court of Exchequer Chamber on Error from the Court of Queen's Bench. With Tables of the Names of the Cases Argued and Cited, and the Principal Matters. S. Sweet.

- Bigelow, Melville (1872). "A treatise on the law of estoppel and its application in practice" (PDF). pp. 23–24.

- "'Do you remember Pomeroy War Memorial Hall in better times?'". Leek Post & Times. 6 November 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2022 – via PressReader.

- "MDR14996 - World War II Pillbox, High Edge, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- "MDR71 - Cairn and Type FW3/23 Pillbox, New High Edge Raceway, Hartington Middle Quarter - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- GENUKI. "Genuki: Earl Sterndale, Derbyshire". www.genuki.org.uk. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- "Peak Advertiser 8.7.13 by Peak Advertiser - Issuu". issuu.com. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- "The 10 most expensive properties sold across Derbyshire in 2021". DerbyshireLive. 28 December 2021. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- SWIFT, ELEANOR (1938). A FERRERS DOCUMENT OF THE TWELFTH CENTURY. p. 162.

- "Hartford - Hartlington". British History Online. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- "MDR14880 - Crowdecote Watermill Complex, Crowdecote - Derbyshire Historic Environment Record". her.derbyshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- Eardley, Denis (2010). Villages of the Peak District. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-3191-2.

- "White's 1857 Directory of Derbyshire - pages 415-428". freepages.rootsweb.com. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- "RAILWAY & CANAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY RAILWAY CHRONOLOGY SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP A Chronology of the CROMFORD & HIGH PEAK RAILWAY" (PDF).

- "Peak National National Park - Hartington Middle Quarter parish statement" (PDF).

- "Hartington Middle Quarter Parish Council – Serving the Residents of Earl Sterndale, Crowdecote, High Needham, Pilsbury and Hurdlow". hartingtonmiddlequarter-pc.org. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "Aldery Cliff". www.ukclimbing.com. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- "Earl Sterndale Flower Festival August 23-25". Hartington Village. 18 August 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- "Home". Earl Sterndale CE Primary School. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "Listed Buildings in Hartington Middle Quarter, Derbyshire Dales, Derbyshire". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Historic England. "Church of St Michael (Grade II) (1109268)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- "Earl Sterndale". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "Pomeroy Memorial Hall". www.warmemorialsonline.org.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "St Michael & All Angels, Earl Sterndale". www.achurchnearyou.com. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "Earl Sterndale Methodist Church, Earl Sterndale, Derbyshire, Church History". churchdb.gukutils.org.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2022.