Hartog Plate

Hartog Plate or Dirk Hartog's Plate is either of two pewter plates, although primarily the first, which were left on Dirk Hartog Island during a period of European exploration of the western coast of Australia prior to European settlement there. The first plate, left in 1616 by Dutch explorer Dirk Hartog, is the oldest-known artifact of European exploration in Australia still in existence. A replacement, copying the text of the original plus some new text, was left in 1697 – the original dish returned to the Netherlands, where it is on display in the Rijksmuseum. Further additions at the site, in 1801 and 1818, led to the location being named Cape Inscription.

Dirk Hartog, 1616

Dirk Hartog was the first confirmed European to see Western Australia, reaching it in his ship the Eendracht. On 25 October 1616, he landed at Cape Inscription on the very northernmost tip of Dirk Hartog Island, in Shark Bay. Before departing, Hartog left behind a pewter dinner plate, nailed to a post and placed upright in a fissure on the cliff top.

The plate bears the inscription:

1616, DEN 25 OCTOBER IS HIER AENGECOMEN HET SCHIP D EENDRACHT

VAN AMSTERDAM, DEN OPPERKOPMAN GILLIS MIBAIS VAN LVICK SCHIPPER DIRCK HATICHS VAN AMSTERDAM

DE 27 DITO TE SEIL GEGHM (sic) NA BANTAM DEN

ONDERCOOPMAN JAN STINS OPPERSTVIERMAN PIETER DOEKES VAN BIL Ao 1616.

Translated into English:

1616, on the 25th October, arrived here the ship Eendracht of

Amsterdam; the upper merchant, Gilles Mibais of Luyck; Captain Dirk

Hartog of Amsterdam; the 27th ditto set sail for Bantam; undermerchant

Jan Stein, upper steersman, Pieter Doekes from Bil, A[nn]o 1616.[1]

Willem de Vlamingh, 1697

Eighty-one years later, in 1697, the Dutch sea captain Willem de Vlamingh also reached the island and discovered Hartog's pewter dish with the post almost rotted away. He removed it and replaced it with another plate which was attached to a new post. The new post was made of a cypress pine trunk taken from Rottnest Island.[2] The original dish was returned to the Netherlands, where it is still kept in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. De Vlamingh's replacement dish contains all of the text of Hartog's original plate as well as listing the senior crew of his own voyage. It concludes with:

1697. Den 4den Februaij is hier aengecomen het schip de GEELVINK voor

Amsterdam, den Comander ent schipper, Willem de Vlamingh van Vlielandt,

Adsistent Joannes van Bremen, van Coppenhagen; Opperstvierman Michil Bloem vant

Sticgt, van Bremen De Hoecker de NYPTANGH, schipper Gerrit Colaart van

Amsterdam; Adsistent Theodorus Heirmans van dito Opperstierman Gerrit

Gerritsen van Bremen, 't Galjoot t' WESELTJE, Gezaghebber Cornelis de

Vlamingh van Vlielandt; Stvierman Coert Gerritsen van Bremen, en van hier

gezeilt met onse vlot den voorts net Zvydtland verder te ondersoecken en

gedestineert voor Batavia.

Translated into English:

On the 4th of February, 1697, arrived here the ship

GEELVINCK, of Amsterdam; Commandant Wilhelm de Vlamingh, of Vlielandt;

assistant, Jan van Bremen, of Copenhagen; first pilot, Michiel Bloem van

Estight, of Bremen. The hooker, the NYPTANGH, Captain Gerrit Collaert, of

Amsterdam, Assistant Theodorus Heermans, of the same place; first pilot,

Gerrit Gerritz, of Bremen; then the galliot WESELTJE, Commander Cornelis

de Vlaming, of Vlielandt; Pilot Coert Gerritz, from Bremen. Sailed from

here with our fleet on the 12th, to explore the South Land, and

afterwards bound for Batavia.[3]

Emmanuel Hamelin, 1801

In 1801, the French captain of the Naturaliste, Jacques Félix Emmanuel Hamelin, second-in-command of an expedition led by Nicolas Baudin in the Geographe entered Shark Bay and sent a party ashore. The party found Vlamingh's plate, even though it was half buried in the sand, as the post had rotted away with the ravages of the weather. When they took the plate to the ship, Hamelin ordered it to be returned, believing its removal would be tantamount to sacrilege. He also had a plate, or similar, of his own prepared and inscribed with details of his voyage (dating to 16 July 1801) and he had both erected at the Vlamingh site, even adding a small Dutch flag to the plaque. It was then named Cape Inscription.[2]

Louis de Freycinet, 1818

In 1818, in the Uranie, French explorer Louis de Freycinet, who had been an officer in Hamelin's 1801 crew, sent a boat ashore to recover Vlamingh's plate and substituted a lead plate, which has never been found.[2] His wife Rose de Freycinet, who was on board, having stowed away with her husband's assistance, recorded the event in what was in effect a diary of her circumnavigation.[4] After being shipwrecked in the Falkland Islands the plate and other materials from the Uranie voyage were later transferred to another ship and taken to France, where the plate was presented to the Académie Française in Paris.[5]

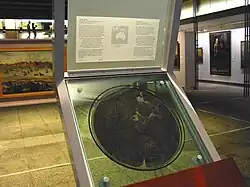

After being lost for more than a century, the Vlamingh plate was rediscovered in 1940 on the bottom shelf of a small room, mixed up with old copper engraving plates.[6] In recognition of Australian losses in the defence of France during the two world wars, the plate was eventually returned to Australia in 1947 and is currently housed in the Western Australian Maritime Museum in Fremantle, Western Australia.[7]

Cape Inscription Lighthouse plaques

Marking the location in 1938, the Commonwealth government commemorated Dirk Hartog's landing with a brass plaque.

Just short of 60 years later, on 12 February 1997, the then-premier of Western Australia Richard Court unveiled a bronze plaque to mark the tricentennial of Vlamingh's visit.[7]

The lighthouse and plaques are located at 25°28′55″S 112°58′19″E.

See also

References

- Vlamingh, Willem de (1976). Schilder, Günter G. (ed.). De ontdekkingsreis van Willem Hesselsz De Vlamingh in de jaren 1696–1697. Werken uitgegeven door de Linschoten-Vereeniging; 78–79. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 9024718775.

- "Dirck Hartogh". Perth, Western Australia: VOC Historical Society. 23 July 2003. Archived from the original on 3 July 2005. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Favenc, Ernest (February 2003) [First published 1888]. "Introduction Part I". The History of Australian Exploration from 1788 to 1888. Sydney: Turner and Henderson – via Project Gutenberg of Australia.

- Rivière, M.S., 1996, A Woman of Courage: The journal of Rose de Freycinet on her voyage around the world 1817–1820. National Library of Australia. Canberra.

- The Uranie Voyage Archived 4 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine at Western Australian Marine Museum, Fremantle

- "Early European History". History. Dirk Hartog Island. Archived from the original on 24 June 2005. Retrieved 29 July 2006.

- Playford, Phillip E. (1998). "A story of two plates". Voyage of discovery to Terra Australis by Willem de Vlamingh in 1696–97. Perth, Western Australia: Western Australian Museum. pp. 51–60. ISBN 0-7307-1221-4. OCLC 39442497.