Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens

Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens, also known as Headingley Zoo and later Leeds Royal Gardens, was open between 1840 and 1858 in Headingley, Leeds, West Yorkshire, approximately two miles out of the city centre and covering the area now occupied by Cardigan Road. It was established following an idea by Dr Disney Thorpe, designed by William Billinton, a Wakefield architect, and built by public subscription during the 1830s.

The zoo was never particularly successful; only part of the envisioned landscape plan was built and it remained in debt for the whole of its existence. The Gardens closed for the first time in December 1848 but were auctioned and then operated for a further ten years before final closure. The site was redeveloped for the construction of Cardigan Road and large villas. There are very few traces of the zoo and gardens now, but remaining artefacts include the Bear Pit, much of the original stone perimeter wall along Chapel Lane, which are both Grade II listed, and many mature trees in what are now private gardens.

History

Founding

Following the industrialisation of England, the newly-dense cities and towns such as Leeds began to find problems with a lack of green spaces for their expanding populations to recreate in. The learned and political classes feared this would lead to increased pursuits like alcohol and gambling, and began to see a risk to public order. It was in these circumstances that the 1833 Select Committee on Public Walks was convened by Parliament to look into the availability of public parks and gardens. One of the people who gave evidence to the committee was the industrialist and Headingley resident John Marshall, who stated that in Leeds, a town which now had a population of 72,000, Woodhouse Moor, Holbeck Moor and Hunslet Moor were the only public open spaces. The recommendation of the select committee was that all towns should build walks at their fringes, funded either by rates or, like many projects of the time, by voluntary subscription. This recommendation was not adopted by Leeds Corporation, but with inter-city rivalries of such concern in the era - botanical gardens were being opened in Sheffield, Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham - individuals within the elite saw the opportunity for a private venture in Leeds.[1]

The idea to establish a pleasure park was proposed in 1836 by Dr Disney Thorpe, a physician at Leeds General Infirmary, who held the vision of inspiring people to spend their leisure time in the fresh country air. In a letter to the Leeds Mercury on 24 December 1836, he wrote:

No one can have failed to have observed that whilst the wealth, importance and population of this town have gradually increased, the opportunities for public recreation have in ratio diminished ... [Enclosures and the spread of buildings] render it everyday more difficult for the labourer and artisan to breath in pure and uncontaminated atmosphere.[1]

Thorpe produced a proposal to raise money for the project via £10 shares in a commercial company. A public meeting to discuss the founding of a Leeds Botanical Gardens was held at the Court House, Park Row, on 22 May 1837, convened by the clerk to the corporation, Edwin Eddison. Thorpe's scheme was agreed at the meeting, with a minimum of £10,000 and a maximum of £20,000 to be raised through shares, and that work would begin once £7,500 (equivalent to £725,000 in 2021) had been raised.[1][2]

During the following week, share sales reached £8,000, more than enough to commence planning for the gardens. The subscription list of 1,100 shows many wealthy Leeds families purchased shares, including two hundred by John Marshall and his son, but also that the majority were ordinary citizens who owned only a small number of shares each. The shareholders elected a committee of 21 to run the scheme day-to-day but had formal authority over the company at its annual general meeting. Though share purchases soon slowed, the project was set in motion as four fields were purchased for £5,000 (equivalent to £483,400 in 2021). Open fields were all that covered the southern slopes of Headingley Hill in the early 19th century, Headingley still at that point being a village separate to the town of Leeds. The four which were chosen for the gardens were formerly part of the Bainbrigge estate, although two were owned by Thorpe himself.[1]

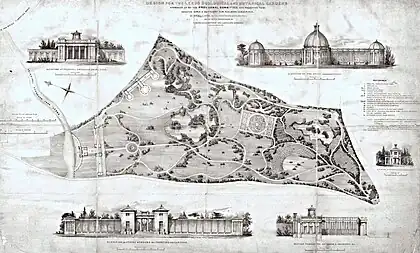

The competition for designs and cost estimates was launched in September 1837, which was marked by the committee and received seventeen designs. The winner was chosen at the end of that year to be William Billinton, a civil engineer and architect from Wakefield, who worked with Edward Davies, a botanist and landscape gardener.[2] Their elaborate plan for the site took substantial inspiration from the leading garden planner John Claudius Loudon, who had designed the Birmingham Botanical Gardens less than a decade earlier, by using a combination of formal elements - such as Classical entrance lodges and glass conservatories - and relaxed scenic elements like a lake, paths, bridges and fountains. Fenced areas for zoological specimens were also included in the plan.[2]

There were already many mature trees in the area, and the land also had several natural watercourses that would help fill up the proposed lakes. A new access road was to be built to the park - Spring Road would be named after these natural springs. If these plans could be realised, then Leeds would have had one of the finest public gardens. However, only around £11,000 was ever raised in shares, forcing much of the design to remain unbuilt. This was compounded by the cost of laying the garden out being four times the estimate, costing £2,000, as the whole site required draining and planting.[2] Other early difficulties included a fire in June 1838 which caused the destruction of one of the buildings and the workshop. As expenses mounted, in February 1840 the committee considered selling or letting the site as a graveyard, for which there was local need, but decided against this, choosing instead to open to the public as soon as possible and hope to recoup funds through general admission.[2]

The formal opening of the gardens took place on 8 July 1840, and featured a crowded ceremony attended by 2,000 people, with flags, bands, and a live demonstration of birds of prey. Reports from contemporaneous local newspapers took different angles on the new gardens; the Leeds Intelligencer disparaged the fountain which had no water and the display with the hawks, which involved the shredding of live birds to show the hawks' natural behaviour.[1] On the other hand, the Leeds Mercury's adulatory report made no mention of those, saying:

Surrounded by a high wall within which on the west, south and east, is a plantation of trees in proper botanical arrangement, and on the north are fruit trees trained against a wall. Beautiful slopes of grass, tasteful parterres and shrubberies, with winding walks, two very handsome ponds with islands and a beautiful fountain. Near the entrance to the grounds from Headingley is a conservatory containing a beautiful collection of geraniums and a variety of exotic plants and flowers. The general appearance of the gardens is exceedingly beautiful, interesting, and lively, and though we hope to see their attractions heightened by the addition of the aviary, conservatories, &c originally intended, yet even at present they form a most attractive place of resort. Great credit is due to the Council, but especially to Mr. Eddison, the Secretaries, and the Curators, who have had nearly all the arrangements on their own shoulders.[3]

An inaugural attraction featuring fireworks and a hot air balloon flight, a popular display of the time, was scheduled to occur on 7 October, but was cancelled due to it taking too long to fill the balloon from the nearest gas supply in Kirkstall.[2]

Operation

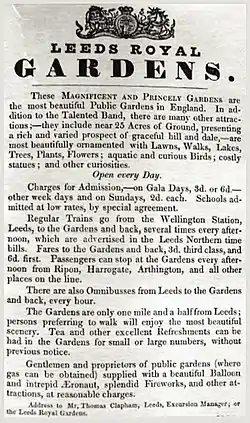

The Gardens charged non-subscribers entry at 6d for adults and 3d for children and servants.[3] This was inexpensive for middle-class visitors, but was a considerable expenditure for workers on an average weekly wage of less than a pound. A number of other factors conspired to keep visitor numbers low; firstly the distance between Leeds and Headingley (with the price of an omnibus augmenting the cost), but mainly the fact it initially did not open on Sundays, which was the only day off for the working classes. Observance of the Sabbath - a day reserved for church, not leisure - was important to the religious moral reformers behind the project's founding and the decision to close on Sundays had been taken in February 1838 at the society general meeting, passing 369 to 202. Some vocal opposition to the move was expressed at the meeting, with a Dr Williamson saying "evils to be apprehended far exceeded any amount of good that could arise from keeping the gardens open".[2]

As the matter went on to affect attendance at the gardens – low visitor numbers made the park suffer heavy losses and ensured no dividends were ever paid – a debate grew in the local newspapers, finally leading to a special general meeting of shareholders in August 1841 at the Philosophical Hall, Bond Street, to consider allowing Sunday opening. A thorough report of the meeting by the Leeds Mercury described the motion discussed, which came with the caveats of only opening after 4 o'clock, and that Sunday tickets should only be available to buy on weekdays. One committee member claimed that not having Sunday opening was the reason for the failure of a recent drive to attract more shareholders, and argued that the choice now lay between allowing Sunday opening or closing the Gardens. However, people who were against it raised issues of the effects on peace, and that it might force servants and cab drivers to work on Sundays. The motion was passed 388 to 34 at the meeting and the Gardens opened on Sundays thereafter.[4]

The Gardens relied for the majority of their income on shows, festivals and galas, such as the annual shows of the Leeds Horticultural and Floral Society, and the Grand County Archery Fete, which was held for two years in the late 1840s.[1] A June 1843 diary entry by Reuben Gaunt, a worsted spinner from Pudsey, reads "Went to the Zoological Gardens, Leeds, to a temperance festival, partook a good tea and after hearing the Trial of John Barleycorn, played various rural sports."[5]

Animals and attractions

Although the Gardens were landscaped and filled with lawns, parterres and shrubberies, the zoological features never reached the size, range, or exoticism of rival zoos of the period. On the day of opening in 1840, the Leeds Mercury reported "The Zoological department as yet is confined to a fine pair of swans and some other fowl, monkeys and tortoises."[3]

When setting up the park in 1838, the committee had explored options for purchasing large animal exhibits, with a budget of £1,000 (equivalent to £95,800 in 2021). One of the people they consulted was George Wombwell, a famous menagerie exhibitor, who was able to advise that for this price, any elephants would be impossible, though it would be viable to buy a pair of lions. He also stressed for the committee that feeding them and employing keepers would mean costs continuing to escalate. Lions were never subsequently purchased. It took until 1843, three years after opening and with disappointing visitor numbers, for the Gardens to obtain their first and only large animal exhibit, a brown bear, which resided in a turretted pit in the middle of the park.[1] It was described as "a very well-bred, decently behaved brown bear"; the eventual collection of animals amounted, in addition to those above, to a raccoon, alligator, guinea pigs, an owl, a peacock, and two parrots.[2]

Demise

Being consistently under-funded and dogged by problems, the Gardens were closed for the first time in December 1848, only eight years after inauguration. A Leeds banker named John Smith bought the site at auction that month for £6,010,[6] with an intention to develop housing, but he sold it again to Henry Cowper Marshall, who had been Mayor of Leeds 1842–43, and the fourth son of the industrialist John Marshall who had given evidence at the original Select Committee and subscribed to the setting up of the gardens.[7]

Another of the original investors, Thomas Clapham, offered to take over running the Zoological and Botanical Gardens and leased them from Marshall. Clapham, originally of Keighley, was 30 years old with fresh ideas for making the park a success.[8] The basis of Clapham's strategy was to change the emphasis of the site from education to entertainment and show, and to take advantage of the new Leeds & Thirsk Railway, which opened in 1849 and brought passengers from Harrogate and Ripon to Leeds, passing right by the Gardens. He renamed the park Royal Gardens and persuaded the railway company to open a station of this name at the southern entrance of the park in Burley.[9] Additionally, Clapham took measures including reducing admission prices to 2d, allowing people to hire it for private occasions, and moving back Sunday opening to 1 o'clock.[1] Despite Clapham's efforts, the reopened park still refused to become profitable and was forced to close for good in 1858. Everything including the land, equipment and even the elderly bear were auctioned off,[8] and the railway station closed, although a new station called Burley Park was built on the same site in 1988 by British Rail. Clapham went on to run another similar attraction next to Woodhouse Moor he named the Royal Park, which also closed due to debts in 1871.[8]

The landowner, Henry Cowper Marshall, returned to the previous plan of developing houses across the site. It was divided into building plots and sold off, with Cardigan Road, which runs from Burley Road to Kirkstall Lane, being driven through the centre of the former zoo in 1868; it was wider and faster than the old Chapel Lane. Villas with large gardens were erected on either side in what was known as the "Old Gardens Estate",[10] resisting the dense back-to-back type of development further down in Hyde Park during this era, with high-quality mansions in every plot by 1893.[11] Several notable local architects designed the villas, including Thomas Ambler, Charles Fowler, George Corson, Edward Birchall, and F W Bedford, making it a rather exclusive development with bespoke houses for prosperous clients. Several have subsequently been demolished and replaced with 1970s apartment buildings.[12]

Present day

.jpg.webp)

Though the substantial structures of the park such as the botanical conservatories were demolished, the lakes infilled, and more roads and buildings built across the site, large areas of the land once owned by the Zoological and Botanical Gardens remains undeveloped in comparison to the surrounding areas, with a more leafy and affluent character compared to Burley and Hyde Park which directly abut the site.[2] The old gardens continue to have an effect on the character, through the tall boundary walls to Chapel Lane, and the retention of deep front garden of the Victorian villas of Cardigan Road. The villa properties are of considerable stature in both height and width, but there are several examples of contemporary infill developments, extensions, conversions and new-build developments in the area.

A number of artefacts remain which can be linked to this relatively brief period in the site's life:

- Parts of the retaining wall by the northern entrance are visible in two places on Spring Road, with one part having been built into the side of a house and the other listed at Grade II and now forming part of a garden wall.[13] Its style of stonework with recessed panels and shallow pilasters can be seen as the "Principal entrance from Leeds" on the illustrated plan (main image).

- Most of the stone boundary wall survives, although cut down considerably in places, and is most intact along Chapel Lane and the length of Back Norwood Terrace[1][10]

- The base of a fountain remains in the garden of Cardigan House[1]

- One of the former lakes leaves a depression within the grounds of Valley Court (flats)[1]

- A small triangle of land bounded by Chapel Lane, Cardigan Road and Spring Road has remained neglected and overgrown due to its unknown ownership. It is now known as Sparrow Park, and was compulsorily purchased by Leeds City Council in 2013, and now has a community group dedicated to maintaining it.[14]

- Many of the large, mature trees along Cardigan Road date back to the existence of the Gardens

The Bear Pit

The most recognisable remnant of the gardens is the Bear Pit, which fronts Cardigan Road. The Victorian structure, a sham castle facade constructed of rock-faced masonry, consists of two circular castellated turrets with round-arched entrances, linked by a wall with a gateway. On the inside, the circular bear pit is brick-lined and is linked to the facing by two tunnels. The bear was viewed by visitors by climbing spiral steps to the tops of the turrets,[15] Metal railings would have been fixed around the pit, and the bear also had a wooden pole to climb up to be fed sandwiches and buns. It was the only large animal exhibit, although there were also smaller cages which housed birds, tortoises and monkeys.[16] Bear-baiting had recently been outlawed by the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835, so they were kept only for display and scientific study.[17][18]

Purchase and restoration of the Bear Pit was one of the first acts of the Leeds Civic Trust, established in 1965.[19] It was purchased for £128 in 1966 and restored at a cost of £1,000 by 1968.[20][21]

The Bear Pit is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a Grade II listed building, having been designated on 5 August 1976.[15] Grade II is the lowest of the three grades of listing, and is applied to "buildings that are nationally important and of special interest".[22]

In 1983, the Civic Trust applied for planning permission to turn the Bear Pit into an open-air theatre, but this proposal was withdrawn.[23] As of September 2016, the Trust had undertaken major rubbish clearance and Japanese knotweed treatment,[24] however the structure remains as a folly, serving no use beyond a casual heritage attraction.

The Bear Pit, Cardigan Road

The Bear Pit, Cardigan Road Inside the overgrown circular pit which contained the bear

Inside the overgrown circular pit which contained the bear

References

- Douglas, Janet (15 February 2018). "The Zoological & Botanical Gardens". Headingley. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Thomason, Kyle (3 January 2020). "Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens: A Brief History". The Secret Library. Leeds Libraries. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Opening of the Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens". The Leeds Mercury. No. 5560. 11 July 1840. p. 5. OCLC 32428267.

- "Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens: Proposed Partial Opening on Sundays". The Leeds Mercury. No. 5619. 14 August 1841. p. 7. OCLC 32428267.

- "Reuben Gaunt, manufacturer of Pudsey, diary". The National Archives. 1841–1854.

- "Sale of the Leeds Public Gardens". Yorkshire Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 30 December 1848. p. 6 col.5. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- Gilleghan, John (2001). "Marshall, John". Leeds: A to Z of local history. Kingsway Press. pp. 166–167. ISBN 0-9519194-3-1.

- Bradford, Eveleigh (February 2014). "They Lived in Leeds: Tommy Clapham (1817-1895)". North Leeds Life. p. 8. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Train". Headingley. 15 February 2018. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Tyler, Richard. "The Old Gardens" (PDF). Headingley Development Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Wrathmell, Susan (2005). Leeds (Pevsner Architectural Guides). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-300-10736-4.

- Trowell 1982, p. 81-85.

- Historic England. "Retaining wall to Leeds Botanical and Zoological Gardens (1256036)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Bolam, Chris (18 June 2013). "Report to Chief Planning Officer: Sparrow Park, Headingley - Proposed Compulsory Purchase Order and subsequent S106 Green space enhancement project". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Historic England. "The Old Bear Pit (1255678)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Johnson, Kristian (22 March 2020). "The crumbling bear pit that still stands on the site of ancient 200 year old Leeds zoo". Leeds Live. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "1835: 5 & 6 William 4 c.59: Cruelty to Animals Ac". The Statutes Project. 3 December 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "The Leeds Zoo: The story of a failed tourist attraction". The Yorkshire Post. 22 September 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "How the Civic Trust shaped Leeds". Yorkshire Evening Post. 21 October 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Historic England (1 April 2017). "Fashionable Fakery: 8 Fantastical Follies". Heritage Calling. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Blyth, Ray (2018). "Leeds". Fabulous Follies. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Listed Buildings, English Heritage, archived from the original on 26 January 2013, retrieved 26 July 2014

- Planning application H26/349/83/ - access via leeds.gov.uk

- "Annual Report 2015/16" (PDF). Leeds Civic Trust. September 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Trowell, Frank (May 1982). Nineteenth-Century Speculative Housing in Leeds (PDF) (PhD). Vol. 1. University of York.

External links

Media related to Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Bear Pit, Headingley at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bear Pit, Headingley at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)