Healthcare in Mexico

Healthcare in Mexico is provided by public institutions run by government departments, private hospitals and clinics, and private physicians. It is largely characterized by a special combination of coverage mainly based on the employment status of the people. Every Mexican citizen is guaranteed no cost access to healthcare and medicine according to the Mexican constitution and made a reality with the “Institute of Health for Well-being”, or INSABI.[1]

The Mexican Federal Constitution places main responsibility on the state in providing national health to the population.[2] This segmentation in the system has allowed private organizations and offices run by physicians to offer a variety of healthcare options to people who can afford it and are willing to pay for it.[3] With Jorge L. León-Cortés research of the background into Mexico's past, it was noted that (2012-2018) there has been an intense uprising of transmittable diseases and very long-term illnesses in the Mexican population with their current life expectances and mortality rate.[4] The overall structure of the Mexican health system is in a continually developing and heterogenous state, and this is reflected in national health statistics and accessibility standards observed in the country.[5][6]

History

In Mexico, the sixteenth century Badianus Manuscript described medicinal plants available in Central America.[7] Dr. Erick Estrada Lugo, Researcher-Professor in Phytotechnics at the State of Mexico's Chapingo Autonomous University, told the National Autonomous University of Mexico’s digital magazine that “at least 90% of the population uses medicinal plants,” citing figures from Mexico's Secretariat of Health. These include plants like Aloe vera, Arnica, and Valeriana.[8]

Hospitals were established in Mexico in the early 16th century, including ones exclusively for Indians. Some were established by the crown, others by private endowment, but most by the Catholic Church. Bishop Vasco de Quiroga established hospital complexes in Michoacan in the sixteenth century. In Mexico City, conqueror Hernán Cortés established the Hospital de Jesús Nazareno for Indians, which still functions as a hospital.[9][10][11]

The Hospicio Cabañas in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, was founded in 1791. It is still functioning and is now a World Heritage Site. It is one of the oldest and largest hospital complexes in Latin America. The complex was founded by the Bishop of Guadalajara to combine the functions of a workhouse, hospital, orphanage, and almshouse.

The Mexican healthcare program, as we know it today, has its base on the creation of several health codes that ran during the first part of the 20th century.[12] In 1943, the Mexican Secretariat of Health and Assistance was established to merge the Department of Public Sanitation and the Secretariat of Public Assistance. In that same year, the Mexican Social Security Institute and the Mexican Children's Hospital were founded, during the presidency of Manuel Avila Camacho.[13] After this, several and important changes came, aiming to provide better health for the population. In 1959, the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE) was formed as a way of more effectively covering the health services of individuals employed in government institutions. The Seguro Popular, or Popular Health Insurance, was implemented countrywide in 2003 after the creation of the Social System during the presidency of Vicente Fox Quesada. In the world's largest randomized health policy experiment, Seguro Popular was evaluated at arm's length by a team at Harvard University, which concluded that "programme resources reached the poor," an unusual result for any country.[14] In 2020 was replaced by the Institute of Health for Welfare (INSABI), which was replaced in 2023 by the IMSS-Bienestar.

Public health

Public health issues were important for the Spanish Empire during the colonial era. Epidemic disease was the main factor in the decline of indigenous populations in the era immediately following the sixteenth-century conquest era and was a problem during the colonial era. The Spanish crown took steps in eighteenth-century Mexico to bring in regulations to make populations healthier.[15] In the late nineteenth century, Mexico was in the process of modernization, and public health issues were again tackled from a scientific point of view.[16][17][18] As in the U.S., food safety became a public health issue, particularly focusing on meat slaughterhouses and meatpacking.[19]

Even during the Mexican Revolution (1910–20), public health was an important concern, with a text on hygiene published in 1916.[20] During the Mexican Revolution, feminist and trained nurse Elena Arizmendi Mejia founded the Neutral White Cross, treating wounded soldiers no matter for what faction they fought. In the post-revolutionary period after 1920, improved public health was a revolutionary goal of the Mexican government.[21][22] The Mexican state promoted the health of the Mexican population, with most resources going to cities.[23][24]

Concern about disease conditions and social impediments to the improvement of Mexicans' health were important in the formation of the Mexican Society for Eugenics. The movement flourished from the 1920s to the 1940s.[25] Mexico was not alone in Latin America or the world in promoting eugenics.[26] Government campaigns against disease and alcoholism were also seen as promoting public health.[27][28]

The Mexican Social Security Institute was established in 1943, during the administration of President Manuel Avila Camacho to deal with public health, pensions, and social security.

Private healthcare delivery

The private healthcare sector makes up a substantial portion of the Mexican healthcare system with respect to both spending and activity. Recently, higher activity within the private sector of the Mexican healthcare system has been observed in comparison to its public counterpart. Overall spending being attributed to the private institutions accounts for approximately 52% of total health spending in the country. Furthermore, this proportion appears to be subject to a sustained increase in recent years.[29] The services provided by private institutions and private physicians in their offices are afforded by a part of the population, either by contracting a private insurance or by paying directly for the services obtained. It is estimated that around 6.9% of the Mexican population has private insurance coverage, mainly paid as an out-of-pocket expenditure. Generally, utilization of this sector of the healthcare system is limited to Mexicans of higher socioeconomic status.[30]

To meet the needs of the population, relationships between the private and public healthcare sectors are beginning to form in various capacities.[31] Recently however, studies have shown little coordination between this system and the other public sector institutions. The high fragmentation of the system has been observed to affect spending trends as well as the services received from beneficiaries.[30]

Private healthcare delivery is a heterogenous institution, with varying levels of regulation, quality, and government association being observed within the institutions which compose it.[32] Mexico has around 28.6 private facilities per 1 million inhabitants, which account for two thirds of all hospitals in Mexico, with 2,988 institutions.[33]

The increased use of the private healthcare sector may be attributed to the association of public forms of healthcare with restriction in accessibility and quality. The belief that these services are superior in quality appears to widespread—many patients depend heavily upon these forms of healthcare, even though public services are at times provided at no cost.[34] Private services tend to be associated with shorter wait times, less crowding, a stronger and more satisfying patient-provider interaction, and higher quality equipment and medications. Additionally, the duration of a visits in a private hospitals tend to be more than double that of their public counterparts.[35] The quality of services performed in these institutions, however, is of debate.[36] Especially in the field of prenatal care, disparities in quality exist among private and public institutions.[37]

In addition to members of the Mexican populace, some individuals with connections to Mexico—including citizens, undocumented immigrants residing in the U.S., and even permanent U.S. residents with Mexican ties—associate private Mexican institutions with convenience, affordability, and efficacy, even rating them above their American public counterparts. This, in turn, has created a phenomenon, known as medical returns, in which select populations, such as migrants, preferentially return to Mexico in order to receive medical treatment.[38]

Additionally, Mexican providers, especially in the private sector, but also in its public counterpart, appear to be less restricted by the possibility of lawsuit in their practice, especially when compared to their equivalent American counterparts, which may contribute to a higher perceived standard of care.[38]

Public healthcare delivery

Public healthcare has an elaborate provisioning and delivery system instituted by the Mexican government. It is provided to all Mexican citizens, as guaranteed by Article 4 of the Constitution.[39]

Public care is fully or partially subsidized by the federal government, depending upon the person's employment status. All Mexican citizens are eligible for subsidized healthcare regardless of their work status via a system of health care facilities operating under the federal Secretariat of Health (formerly the Secretaría de Salubridad y Asistencia, or SSA) agency through the program called INSABI which offers coverage to Mexicans who do not have formal employment.[39] The program currently protects over 57 million inhabitants and covers all conditions, services and medicine free of charge. This public insurance scheme, coupled with Social Security, represents 95% of the insured population in Mexico.[40] Funding for INSABI is derived from the federal government, the Secretariat of Health, and the individuals who form a part of this system. However, approximately 20% of individuals in this system, representing the poorest covered sector, are exempt from this.[41]

Employed citizens and their dependents, however, can use the program administered and operated by the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) (English: Mexican Social Security Institute). The IMSS program is a tripartite system funded equally by the employee, the private employer, and the federal government. There are more than 65 million people covered through IMSS and its programs.[42] Further, within IMSS there exists the IMSS-Opportunidades, a program established out of the Program to Combat Poverty, which is specifically targeted towards aiding the poorest individuals in the country in both the health and educational fields. This program is completely funded by the government.[41]

The IMSS does not provide service to public employees, who instead are serviced by the Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado (ISSSTE) (English: Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers), which attends to the health and social care needs of government employees at the local, state, and federal levels. Nearly 9 million people are covered by the ISSSTE.[42]

The state governments of Mexico also provide health services independently of those that are provided by the federal government programs. In most states, the state government has established free or subsidized healthcare to all of its citizens.[43]

The Secretariat of Health is the largest public healthcare institution, operating 809 hospitals throughout the country. The IMSS grants hospital care and services to employed citizens and their dependents and had 279 hospitals affiliated to it. The ISSSTE grants hospital care and services to government employees and has 115 affiliated hospitals. The other 279 hospitals are affiliated with 9 government dependencies, including State Facilities, Secretariat of National Defense (Secretaria de Defensa Nacional), Mexican Navy (Secretaria de Marina), Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), and the Red Cross (Cruz Roja).[44] The health systems associated with SEDENA, SEMAR, and PEMEX cover over one million individuals combined.[41]

In 2007, there were a total of 23,858 health units within the Mexican state. Approximately 27% of these were contained in the public sector.[41]

Health Reform/Coverage

León-Cortés, Fernández, and Sánchez-Pérez noted that before the health reform plan of 2012–2018, the E. Peña Nieto's administration took action to help the Mexican population, which was facing a large health crisis. Sustainability of life was at an all-time low and impacted many. The Administration had high hopes that the health reform plan would offer better healthcare for the lower income population of Mexico with the idea of providing better healthcare deals when it came to health issues.[4] The population of Mexican families in poverty struggled with healthcare benefits due to their labor status. At the end of 2018, the Sistema de Protección Social en Salud (SPSS – Social Health Protection System) gave most of the lower income families of Mexico access to better benefits.[45] Health reform in Mexico was developing as they learned from trial and error. Many public healthcare facilities were changing this reform by providing greater healthcare services. There was much investment into completely reforming many of its original foundations which included advancing medical technology and better resources for the healthcare facility members.[46]

Health statistics

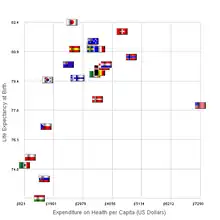

Mexico has seen an overall improvement in almost every aspect of health trend.[5] However, Mexico lags well behind other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries in health status and availability.[47]

| 2016 | |

|---|---|

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | 77.5* |

| Life expectancy at birth, male (years) | 75.1* |

| Life expectancy at birth, female (years) | 79.9* |

| Maternal mortality ratio

(reported, per 100,000) |

36.7 |

| Mortality rate from communicable diseases (age-adjusted per 100,000) | 52.1 |

| Mortality rate from non-communicable diseases (age-adjusted per 100,000) | 469.6 |

| Mortality rate from external causes

(age-adjusted rates per 100,000) |

56.6 |

| Mortality from breast cancer, female

(age-adjusted rates per 100,000) |

11.2 |

| Mortality from lung cancer

(age-adjusted rates per 100,000) |

6.4 |

| Mortality from ischemic heart diseases

(age-adjusted rates per 100,000) |

83.2 |

| Mortality from cerebrovascular diseases

(age-adjusted rates per 100,000) |

30.0 |

| Mortality from homicide

(age-adjusted rates per 100,000) |

35.5 |

| Tobacco consumption among adults

(age adjusted, %) |

14.2 |

| Alcohol consumption among adults

(liters/per person/year) |

6.5 |

| Overweight and obesity, male

(age-adjusted, %) |

63.6 |

| Overweight and obesity, female

(age-adjusted, %) |

66.0 |

| Overweight and obesity in children aged < 5 years (%) | 5.2** |

| Hospital births (%) | 92.7 |

| Antenatal care coverage by skilled birth attendants of 4+ visits (%) | 89.5 |

| Number of physicians (per 10,000 population) | 24.0 |

| Number of nurses (per 10,000 population) | 29 |

| Number of dentists (per 10,000 population) | 1.9 |

| *Data from 2018

**Data from 2012 | |

| Cause | Deaths (per 100,000) |

Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular diseases | 127.82 | 22.74% |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 102.15 | 18.18% |

| Neoplasms | 76.86 | 13.68% |

| Digestive diseases | 49.39 | 8.79% |

| Self-harm and interpersonal violence | 40.19 | 7.15% |

| Neurological diseases | 32.72 | 5.82% |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 27.11 | 4.82% |

| Respiratory infections and Tuberculosis | 19.44 | 3.46% |

| Other non-communicable diseases | 17.32 | 3.08% |

| Unintentional injuries | 17.03 | 3.03% |

| Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation [49] |

Health expenditure

Total health expenditure represented around 5% of GDP in 1995, which went up to around 6.2% in 2012; however, in 2015 it declined to 5.6%. Historically, out-of-pocket expenditure has been a big portion of health expenditure, going from around 56% in 1995 to below 50% since 2008, with the most recent data being 40.6% in 2015.[5][48] Recent reform has seen the establishment of new special funding programs, as well as more progressive limits on patient contribution was also included. Funding was restructured in a manner that both promoted coverage through incentives directed towards state-level governments and reassessment of funding on a need-level basis.[50]

Health demographics

According to recent international statistics, Mexico has an estimated population of 130 millions of inhabitants, with a reported annual population growth rate of 1.2%. Since 1990 there was an increment of about 45 million people.[5]

Demographic transition have been notorious in the last 7 decades in Mexico. Life expectancy at birth (general) changed from being 45 years in 1950 to 71.5 years in 1990, and to actually reach 77.5 years, close to some high-income countries in America and the World.[48][51] Child mortality rate, as one of the major health trends, have improved most notoriously after 1950, when an average of 252 children under-five years were dead per 1000 live births, decreasing to 44.5 in 1990 and reaching 14.6, in 2018.[48][51] Finally, after 1970, at least 20 years after the major changes in life expectancy and child mortality rate, there was a decrease in fertility rate. In 1950 it was estimated that for every woman, around 6.67 babies were born; in 1970, it increased to 6.8 and then, steadily decreased to 3.4 in 1990 to finally end in 2.1, which is below the world average.[48][51]

Besides this demographic transition, there have been major changes in the principal causes of death and morbidities among Mexicans. Epidemiological transition has been notorious in the history of Mexico when it comes to Disability-adjusted life year (DALY) but not when comparing causes of death, with most data coming since 1990.[52][53] According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, in 1990 the leading causes of death in the country were also cardiovascular diseases, neoplasms and diabetes, which remain the same until recent data. Some infectious diseases (respiratory infections, tuberculosis and enteric infections) were also among the most common causes in the 90's, which were displaced for other non-communicable diseases in 2017. Taking into consideration the burden of disease according to the years lost due to disability (DALY), in 1990, the three most common causes of disability were communicable and maternal diseases (maternal and neonatal disorders, respiratory infections, tuberculosis and enteric infections). In 2017, these 3 diseases were replaced by diabetes and kidney diseases, cardiovascular diseases and self-injuries, displacing most of the communicable diseases out of the top ten.[49][52]

Diabetes

The prevalence of diabetes is rapidly increasing on a global scale. One of the countries in which such precipitous growth has been observed is in Mexico. The proportion of the country with diagnosed diabetes mellitus increased roughly four times from 1993 to 2006, where it directly affected close to a quarter of the population. The impact of this disease on overall mortality increased by over twenty times in the same thirteen-year period, and future projections see this figure only increase.[54] In 2011 alone, health spending attributed to diabetes in the country amounted to almost eight billion dollars. A staggering amount of this spending is in the form of out-of-pocket expenses. This economic burden is most strongly pronounced on the uninsured population. The prominence of this disease in national healthcare system, and especially the financial implications derived from this are significant. A study conducted by Arredondo and Reyes found that the financial aspects of this alone have been observed to generate independent health disparities.[54] Additionally, a large proportion of severe health complications, such as heart attacks and renal disease, can be determined to stem directly from this epidemic. In Mexico, where the health system is subject to unique segmentation, this issue poses an amplified public health and economic challenge. The public healthcare system is overwhelmingly utilized in the management of this disease and its secondary developments— with only ten percent of population depending on the private sector for care.[54]

Accessibility

The Mexican healthcare system remains a continually expanding and progressive structure. Mexico first began enacting initiatives to extend health coverage, particularly in rural communities in 1979. Data from a national survey in 2012 demonstrated that a majority of Mexicans maintain a positive perception on the quality of their primary care.[55] In 2013, a report by the Ministry of Health projected that over 90% of the population was covered.[56] There are some areas, though, were inequities in accessibility can be seen. Results from a national survey conducted by Arredondo and Najera (2008) revealed stark disparities in accessibility despite expansion of services and coverage association, demonstrating that despite enhancements to the national health systems, inequities in accessibility of institutions, care, diagnostic services, medication, and travel were pronounced, especially as it related to rural and impoverished communities. These include insurance coverage, cost reduction, primary care association, and specialized services accessibility.[6][55][57][58]

Insurance coverage

Insurance coverage rates across Mexico have been marked by a recent period of large growth. The induction of Seguro Popular (Popular Health Insurance), the coverage program targeted at individuals who do not receive coverage under IMSS or ISSSTE,[40] in 2003 spurred massive growth in insurance coverage across Mexico. A couple years after the plan was introduced, Seguro Popular became the second largest health institution by coverage in the nation. Within this, the percentage of insured poor families increased by five times— to include more than a third of this demographic. Inequities between public and private expenditure, as well as the distribution of these expanded services, began to lessen.[50] In 2015, it was projected that the proportion of the Mexican population with no access to health insurance decreased by close to seventy percent across this period, with only about 18% of the population falling under this group currently. This effect has been particularly effective in treating the older demographics.[57] Furthermore, in 2012, it was observed that 4.3 million households in the nation possessed no health coverage of any kind, with an additional 7.6 million households associated with partial coverage of some members only.[40]

In Mexico, where government-sponsored health insurance coverage remains a stark limitation characteristic of the system, self-medication is observed in increased proportions. Over 30 million Mexicans, especially those associated with older, uneducated, and low socioeconomic backgrounds. This may be indicative of societal attitudes toward the current system. This notion is furthered by the large proportions of residents which postpone reception of initial services, have little-to-no connection to a preventative care specialist, and heavily utilize alternative medicinal practice. Over 500 over-the-counter drugs are available in the Mexican market. This enhanced availability of over-the-counter drugs has also contributed to this phenomenon.[59]

Cost

Cost of healthcare services in Mexico is variable and dependent on the nature of the service and the institution utilized. Generally, health costs associated with use of the public healthcare sector are higher than their private counterparts.[41] Furthermore, individuals not insured under any current health insurance scheme most often utilize private doctors instead of public institutions. A study conducted in 2015 by Doubova et al. determined that roughly four percent of the uninsured population was faced with catastrophic expenditure of some sort at some point. Additionally, it was found that over half of uninsured individuals had not accessed care despite having a health issue due to financial issues.[57] Additionally, a report by Munoz (2013) established that in the period following the implementation of the new 2003 health reform to the end of the decade, out-of-pocket patient expenditures, related to hospitalization, visit, medicine, diagnostic tests, alternative options, dental care, prolonged treatments, among others, had remained relatively similar.[57]

Comparative analysis of the cost of Mexican healthcare services costs has been performed by analysts. In 1992, the New York Times reported that residents of the United States living near the Mexican border routinely crossed into Mexico for medical care.[60] Popular specialties included dentistry and plastic surgery. In 2007, The Washington Post reported that Mexican dentists charged 20-25% of US prices,[61] and other procedures typically cost a third of the US price.[60]

Problems of lack of access to healthcare

Factors that have demonstrated influence on the magnitude of accessibility available to healthcare include sparse distribution of institutional resources, and lack of specialized care services in isolated populations.[58][62] Case studies involving clinical management of diarrheic disease in rural communities have emphasized concerns relating to the quality and range of services available to more isolated populations.[62] Accessibility as it relates to rural communities has been a heavily studied topic and work here has revealed the existence of great disparities in breadth and effectiveness of services offered. Issues related to accessibility of specialized services, especially institutions offering forms of care related to mental health, are prevalent in rural communities. Factors such as location, transportation, and the economic cost of implementation are the main factors associated with this.[58]

Mental health

The 1990 Regional Conference for the Restructuring of Psychiatric Care in Latin America established guidelines that the Mexican government has sought to keep.[63] The Caracas Declaration, issued during the conference, recognized the need to protect the rights of individuals with non-physical disabilities and called for mental health to be integrated with primary care.[63] Created with the goal of aligning Mexico with global recommendations issued by the World Health Organization, the National Council on Mental Health (Consejo Nacional de Salud Mental) was created as part of the federal Health Ministry in 2004.[64] Although the restructuring of psychiatric care began in the 1990s with the Regional Conference for the Restructuring of Psychiatric Care in Latin America, psychiatric care was found to be inadequate and in need of a larger budget.[65] Though it mentioned mental health care, the 2004 Seguro Popular did not succeed in its goals of improving access to health insurance or mental health care for low-income individuals.[66] In 2003, it was projected that up to a quarter of the population was afflicted with some form of mental illness. Rural populations made up especially large proportions of this demographic.

Rural remoteness

Due to political and socioeconomic factors, Mexico's Indigenous communities are one of the groups that has faced inequities in mental health care. Indigenous communities are likely to live in remote areas where they may be unable to access health services, exposed to pollution, and live in areas being exploited for their natural resources.[67] Although studies have found that it is socio-economic status as opposed to ethnicity that influences the use of programs like SP, Indigenous communities are more likely to live in extreme poverty.[68] Treatment for mental health in Indigenous communities also encounters a cultural barrier. Although the need for services exists, treatment has been typically conducted by community "healers".[64] The negative stigma that mental health carries is seen to prevent treatment carried during early indication periods.[64]

Urban populations are also subject to unique issues and conflicts, mostly related to delivery and the ability of the institutions to service the large populations they are associated with.[32]

Preventative care

Preventative care is still an under-focused area across the country. A 2015 projection model found that almost a quarter of the Mexican population did not have a regular primary care provider or institution that year.[55]

Mexico is facing a steady incline of cancer across their low-income population, mostly with breast cancer and health facilities were taking a major hit to combat it. As more advanced technology for cancer development was released, studies showed a huge decrease in breast cancer related deaths as health facilities insisted more people to get regular checkups.[69] Many people of Mexico are continuing to move into larger cities in which the smaller rural and urban comminutes are becoming increasingly overcrowded. With the new growth in population the cities are struggling to build and provide housing only for this to skyrocket air pollution rates. Calderón-Garcidueñas noted that many of the young children's nervous systems were under attack which alarmed many not just over children's overwhelming health concerns, but adult health issues as well.[70] Even though the Mexican Healthcare system has improved greatly over many years of reform, it has been incredibly unattainable with the cost for healthcare when it comes to out-of-pocket situations. International Journal for Equity in Health explained that this is not the only problem the population of Mexico is facing, many of the hospitals are delivering low quality services, not enough medicine to treat illnesses, and mistreatment. [71]

Universal health care

On December 1, 2006, the Mexican government created the Health Insurance for a New Generation (also called "Life Insurance for Babies").[72][73][74] It was followed by a February 16, 2009, announcement by President Felipe Calderon, who stated that at the current rate, Mexico would have universal health coverage by 2011,[75] and a May 28, 2009 announcement of universal coverage for pregnant women.[76] In August 2012 Mexico achieved universal healthcare coverage.[77]

See also

References

- Bienestar, Instituto de Salud para el. "Instituto de Salud para el Bienestar". gob.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Gutiérrez, N. Mexico: Availability and Cost of Health Care-Legal Aspects Archived 2020-04-06 at the Wayback Machine. The Law Library of Congress; 2014.

- ManattJones Global Strategies. Mexican Healthcare System Challenges and Opportunities Archived 2020-04-06 at the Wayback Machine. Washington: ManattJones Global Strategies; 2015.

- León-Cortés, Jorge L.; Leal Fernández, Gustavo; Sánchez-Pérez, Héctor J. (2019-02-07). "Health reform in Mexico: governance and potential outcomes". International Journal for Equity in Health. 18 (1): 30. doi:10.1186/s12939-019-0929-y. ISSN 1475-9276. PMC 6367748. PMID 30732653.

- "Health in the Americas+, 2017 Edition. Summary: Regional Outlook and Country Profiles". Scientific and Technical Publication. 642. September 2017. hdl:10665.2/34321. ISBN 9789275119662.

- Arredondo, Armando; Nájera, Patricia (December 2008). "Equity and accessibility in health? Out-of-pocket expenditures on health care in middle income countries: evidence from Mexico". Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 24 (12): 2819–2826. doi:10.1590/S0102-311X2008001200010. PMID 19082272.

- Gimmel Millie (2008). "Reading Medicine In The Codex De La Cruz Badiano". Journal of the History of Ideas. 69 (2): 169–192. doi:10.1353/jhi.2008.0017. PMID 19127831. S2CID 46457797.

- DANIA VARGAS AUSTRYJAK. "5 MEXICAN PLANTS TO KEEP YOU HEALTHY". mexiconewsnetwork. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- David Howard, The Royal Indian Hospital of Mexico City, Tempe: Arizona State University Center for Latin American Studies, Special Studies 20, 1979.

- Venegas Ramírez, Carmen (1973). Régimen hospitalario para indios en la Nueva España. OCLC 253838189.

- Josefina Muriel, Hospitales de la Nueva España. 2 vols. Mexico 1956-60.

- "Antología de la Atención a la Salud en México, 1902-2002". PAHO. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- Hawley, Chris (31 August 2009). "Mexico's health care lures Americans". USA Today. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- King, Gary; Gakidou, Emmanuela; Imai, Kosuke; Lakin, Jason; Moore, Ryan T; Nall, Clayton; Ravishankar, Nirmala; Vargas, Manett; Téllez-Rojo, Martha María; Ávila, Juan Eugenio Hernández; Ávila, Mauricio Hernández; Llamas, Héctor Hernández (2009). "Public policy for the poor? A randomised assessment of the Mexican universal health insurance programme". The Lancet. 373 (9673): 1447–1454. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60239-7. PMID 19359034.

- Donald Cooper, Epidemic Disease in Mexico City, 1761–1813: An Administrative, Social, and Medical History. Austin: University of Texas Press 1965.

- Agostoni, Claudia. Monuments of Progress: Modernization and Public Health in Mexico City, 1876–1910. Calgary: University of Calgary Press; Boulder: University of Colorado Press; Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricos 2003.

- Soto Laveaga, Gabriela; Agostoni, Claudia (2011-04-20), Beezley, William H. (ed.), "Science and Public Health in the Century of Revolution", A Companion to Mexican History and Culture, Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 561–574, doi:10.1002/9781444340600.ch33, ISBN 978-1-4443-4060-0

- Alexander, Anna Rose, City on Fire: Technology, Social Change, and the Hazards of Progress in Mexico City, 1860–1910. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 2016.

- Pilcher, Jeffrey M. The Sausage Rebellion: Public Health, Private Enterprise, and Meat in Mexico City, 1890–1917. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2006.

- Pani, Alberto J. (1916). La higiene en México (in Spanish). Mexico: Imprenta de J. Ballescá.

- Bliss, Katherine (1999-02-01). "The Science of Redemption: Syphilis, Sexual Promiscuity, and Reformism in Revolutionary Mexico City". Hispanic American Historical Review. 79 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1215/00182168-79.1.1. PMID 21162337.

- Ernesto Aréchiga Córdoba, "Educación, propaganda o 'Dictadura sanitaria'. Estrategias discursivas de higiene y salubridad pública en el México posrevolucionario, 1917–1934". Dynamis 25, 2005, pp. 117–143.

- Anthony J. Mazzaferri, "Public Health and Social Revolution in Mexico." PhD dissertation, Kent State University 1968.

- David Sowell, Medicine on the Periphery: Public Health in Yucatán, 1870–1960. Lanham: Lexington Books 2015.

- Stern, Alexandra Minna (1999). "Responsible mothers and normal children: eugenics, nationalism, and welfare in post-revolutionary Mexico, 1920-1940". Journal of Historical Sociology. 12 (4): 369–398. doi:10.1111/1467-6443.00097. PMID 21987856.

- Nancy Leys Stepan, The Hour of Eugenics: Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press 1991.

- Pierce, Gretchen (2011-04-20), Beezley, William H. (ed.), "Fighting Bacteria, the Bible, and the Bottle: Projects to Create New Men, Women, and Children, 1910-1940", A Companion to Mexican History and Culture, Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 505–517, doi:10.1002/9781444340600.ch30, ISBN 978-1-4443-4060-0

- T. Mitchell, Intoxicated Identities: Alcohol's Power in Mexican History and Culture. Routledge 2004.

- Carvalho, Regina R. P.; Fortes, Paulo A. C.; Garrafa, Volnei (April 2014). "[Reflections on public-private participation in healthcare]". Salud Publica de Mexico. 56 (2): 221–225. PMID 25014429.

- Juan López, Mercedes; Martínez Valle, Adolfo; Aguilera, Nelly (2015-04-03). "Reforming the Mexican Health System to Achieve Effective Health Care Coverage". Health Systems & Reform. 1 (3): 181–188. doi:10.1080/23288604.2015.1058999. PMID 31519078. S2CID 71031857.

- Rudman, Andrew (20 October 2016). "Mexico's Healthcare Opportunities: Growing Demand for Private Sector Alternatives". Lexology. Manatt Phelps & Phillips LLP.

- Barraza-Lloréns, Mariana; Bertozzi, Stefano; González-Pier, Eduardo; Gutiérrez, Juan Pablo (May 2002). "Addressing Inequity In Health And Health Care In Mexico". Health Affairs. 21 (3): 47–56. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.47. PMID 12026003. S2CID 9902063.

- OECD (June 30, 2005). Estudios de la OCDE sobre los Sistemas de Salud: México 2016 [OECD Studies on Health Systems: Mexico 2016] (in Spanish). OECD Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 978-92-64-26552-3.

- Das, Jishnu; Hammer, Jeffrey; Leonard, Kenneth (2008-03-01). "The Quality of Medical Advice in Low-Income Countries". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 22 (2): 93–114. doi:10.1257/jep.22.2.93. PMID 19768841. S2CID 39190175.

- Finkler, Kaja (June 1994). "Sacred Healing and Biomedicine Compared". Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 8 (2): 178–197. doi:10.1525/maq.1994.8.2.02a00030.

- Barber, Sarah L. (2006-08-01). "Public and private prenatal care providers in urban Mexico: how does their quality compare?". International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 18 (4): 306–313. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzl012. PMID 16675474.

- Villar, José; Valladares, Eliette; Wojdyla, Daniel; Zavaleta, Nelly; Carroli, Guillermo; Velazco, Alejandro; Shah, Archana; Campodónico, Liana; Bataglia, Vicente; Faundes, Anibal; Langer, Ana (June 2006). "Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America". The Lancet. 367 (9525): 1819–1829. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68704-7. PMID 16753484. S2CID 42532286.

- Horton, Sarah; Cole, Stephanie (June 2011). "Medical returns: Seeking health care in Mexico". Social Science & Medicine. 72 (11): 1846–1852. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.035. PMID 21531062.

- Gómez, C. The Health System in Mexico. Mexico: Revista Conamed, Vol. 22 Núm 3; 2017.

- Urquieta-Salomón, José E; Villarreal, Héctor J (February 2016). "Evolution of health coverage in Mexico: evidence of progress and challenges in the Mexican health system". Health Policy and Planning. 31 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1093/heapol/czv015. PMID 25823751.

- Castro, Roberto (2014). "Health Care Delivery System: Mexico". The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Health, Illness, Behavior, and Society. pp. 836–842. doi:10.1002/9781118410868.wbehibs101. ISBN 978-1-118-41086-8.

- Secretaría de la Función Pública. Confronta al primer trimestre 2016 de los padrones del Sistema Nacional de Salud: Resumen Ejecutivo. Mexico: Secretaría de la Función Pública; 2016.

- Quienes Somos. Archived 2009-07-21 at the Wayback Machine Secretaria de Salud. Federal Government of Mexico. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- National Health Information System, "SINAIS" Archived 2015-01-25 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- Rabiul Islam, Md.; Hasan, Moynul; Rahman, Mohammad Saydur; Rahman, Md. Ashrafur (September 2022). "Monkeypox outbreak – No panic and stigma; Only awareness and preventive measures can halt the pandemic turn of this epidemic infection". The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 37 (5): 3008–3011. doi:10.1002/hpm.3539. ISSN 0749-6753.

- Frenk, Julio (October 25, 2006). "Comprehensive reform to improve health system performance in Mexico".

- Country profile: Mexico. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (July 2008).

- Pan American Health Organization (2018). Health Situation in the Americas. Core Indicators 2018. Washington, DC: PAHO. hdl:10665.2/49511.

- "GBD Compare". Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Seattle, WA: University of Washington. 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- Frenk, Julio; González-Pier, Eduardo; Gómez-Dantés, Octavio; Lezana, Miguel A; Knaul, Felicia Marie (October 2006). "Comprehensive reform to improve health system performance in Mexico". The Lancet. 368 (9546): 1524–1534. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69564-0. PMID 17071286. S2CID 16441856.

- "Gapminder Data". Gapminder. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- Gómez-Dantés, Héctor; Fullman, Nancy; Lamadrid-Figueroa, Héctor; Cahuana-Hurtado, Lucero; Darney, Blair; Avila-Burgos, Leticia; Correa-Rotter, Ricardo; Rivera, Juan A.; Barquera, Simon; González-Pier, Eduardo; Aburto-Soto, Tania (2016-11-12). "Dissonant health transition in the states of Mexico, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". The Lancet. 388 (10058): 2386–2402. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31773-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 27720260. S2CID 30999811.

- Stevens, Gretchen; Dias, Rodrigo H.; Thomas, Kevin J. A.; Rivera, Juan A.; Carvalho, Natalie; Barquera, Simón; Hill, Kenneth; Ezzati, Majid (2008-06-17). "Characterizing the Epidemiological Transition in Mexico: National and Subnational Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors". PLOS Medicine. 5 (6). e125. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050125. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 2429945. PMID 18563960.

- Arredondo, Armando; Reyes, Gabriela (2013-07-12). Folli, Franco (ed.). "Health Disparities from Economic Burden of Diabetes in Middle-income Countries: Evidence from México". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e68443. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...868443A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068443. PMC 3709919. PMID 23874629.

- Doubova, Svetlana V; Guanais, Frederico C; Pérez-Cuevas, Ricardo; Canning, David; Macinko, James; Reich, Michael R (September 2016). "Attributes of patient-centered primary care associated with the public perception of good healthcare quality in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and El Salvador". Health Policy and Planning. 31 (7): 834–843. doi:10.1093/heapol/czv139. PMID 26874326.

- Secretaria de Salud. (2013). Programa Nacional De Desarrollo 2013-2018. Retrieved from http://www.conadic.salud.gob.mx/pdfs/sectorial_salud.pdf

- Doubova, Svetlana V; Pérez-Cuevas, Ricardo; Canning, David; Reich, Michael R (July 2015). "Access to healthcare and financial risk protection for older adults in Mexico: secondary data analysis of a national survey". BMJ Open. 5 (7): e007877. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007877. PMC 4513520. PMID 26198427.

- Salgado-de Snyder, V Nelly; Díaz-Pérez, Ma de Jesús; González-Vázquez, Tonatiuh (January 2003). "Modelo de integración de recursos para la atención de la salud mental en la población rural de México". Salud Pública de México. 45 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1590/S0036-36342003000100003. PMID 12649958.

- Pagán, José A.; Ross, Sara; Yau, Jeffrey; Polsky, Daniel (January 2006). "Self-medication and health insurance coverage in Mexico". Health Policy. 75 (2): 170–177. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.03.007. PMID 16338480.

- Hilts, Philip J. (1992-11-23). "Quality and Low Cost of Medical Care Lure Americans to Mexican Doctors". The New York Times. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- Roig-Franzia, Manuel (2007-06-18). "Discount Dentistry, South of The Border". Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- Reyes, H.; Tomé, P.; Gutiérrez, G.; Rodríguez, L.; Orozco, M.; Guiscafré, H. (July 1998). "[Mortality for diarrheic disease in Mexico: problem of accessibility or quality of care?]". Salud Publica de Mexico. 40 (4): 316–323. doi:10.1590/S0036-36341998000400003. PMID 9774900.

- Caldas de Almeida, José Miguel; Horvitz-Lennon, Marcela (2010-03-01). "Mental Health Care Reforms in Latin America: An Overview of Mental Health Care Reforms in Latin America and the Caribbean". Psychiatric Services. 61 (3): 218–221. doi:10.1176/ps.2010.61.3.218. ISSN 1075-2730. PMID 20194395.

- Duncan, Whitney L. (2017). "Psicoeducación in the land of magical thoughts: Culture and mental-health practice in a changing Oaxaca". American Ethnologist. 44 (1): 36–51. doi:10.1111/amet.12424. ISSN 1548-1425.

- Berenzon Gorn, Shoshana; Saavedra Solano, Nayelhi; Medina-Mora Icaza, María Elena; Aparicio Basaurí, Víctor; Galván Reyes, Jorge (April 2013). "Evaluación del sistema de salud mental en México: ¿hacia dónde encaminar la atención?". Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 33 (4): 252–258. doi:10.1590/s1020-49892013000400003. ISSN 1020-4989. PMID 23698173.

- Homedes, Núria; Ugalde, Antonio (2009-08-18). "Twenty-Five Years of Convoluted Health Reforms in Mexico". PLOS Medicine. 6 (8): e1000124. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000124. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 2719806. PMID 19688039.

- Cianconi, Paolo; Lesmana, Cokorda Bagus Jaya; Ventriglio, Antonio; Janiri, Luigi (2019-04-12). "Mental health issues among indigenous communities and the role of traditional medicine". International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 65 (4): 289–299. doi:10.1177/0020764019840060. ISSN 0020-7640. PMID 30977417. S2CID 109939427.

- Leyva-Flores, Rene; Servan-Mori, Edson; Infante-Xibille, Cesar; Pelcastre-Villafuerte, Blanca Estela; Gonzalez, Tonatiuh (2014-08-06). Caylà, Joan A. (ed.). "Primary Health Care Utilization by the Mexican Indigenous Population: The Role of the Seguro Popular in Socially Inequitable Contexts". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e102781. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j2781L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0102781. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4123888. PMID 25099399.

- Chávarri-Guerra, Yanin; Villarreal-Garza, Cynthia; Liedke, Pedro ER; Knaul, Felicia; Mohar, Alejandro; Finkelstein, Dianne M.; Goss, Paul E. (2012). "Breast cancer in Mexico: A growing challenge to health and the health system". The Lancet Oncology. 13 (8): e335–e343. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70246-2. PMID 22846838.

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, Lilian; Kulesza, Randy J.; Doty, Richard L.; D'Angiulli, Amedeo; Torres-Jardón, Ricardo (2015-02-01). "Megacities air pollution problems: Mexico City Metropolitan Area critical issues on the central nervous system pediatric impact". Environmental Research. 137: 157–169. Bibcode:2015ER....137..157C. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2014.12.012. ISSN 0013-9351. PMID 25543546.

- Martínez-Martínez, Oscar A.; Rodríguez-Brito, Anidelys (2020-02-10). "Vulnerability in health and social capital: a qualitative analysis by levels of marginalization in Mexico". International Journal for Equity in Health. 19 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/s12939-020-1138-4. ISSN 1475-9276. PMC 7011273. PMID 32041618.

- Tapia, Monserrat Barrera (September 2, 2007). "Message to the Nation from the President of Mexico, Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, on the occasion of his first State of the Union Address". México - Presidencia de la República. Sistema Internet de la Presidencia. Archived from the original on December 21, 2009. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- Walker, Suzanne Stephens (August 13, 2007). "President Calderón during First National Week of Affiliation to Medical Insurance for a New Generation". México - Presidencia de la República. Sistema Internet de la Presidencia. Archived from the original on December 21, 2009. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- Tapia, Monserrat Barrera (February 26, 2008). "President Calderón at Launching of Affiliation to Medical Insurance for a New Generation". México - Presidencia de la República. Sistema Internet de la Presidencia. Archived from the original on December 21, 2009. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- Walker, Suzanne Stephens (February 16, 2009). "Mexico to Achieve Universal Health Coverage by 2011: President Calderón". México - Presidencia de la República. Sistema Internet de la Presidencia. Archived from the original on December 21, 2009. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- Walker, Suzanne Stephens (May 28, 2009). "International Women's Day". México - Presidencia de la República. Sistema Internet de la Presidencia. Archived from the original on December 21, 2009. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- "Mexico achieves universal health coverage, enrolls 52.6 million people in less than a decade". Harvard School of Public Health. 2012-08-15. Retrieved 2013-09-16.