Quality of life (healthcare)

In general, quality of life (QoL or QOL) is the perceived quality of an individual's daily life, that is, an assessment of their well-being or lack thereof. This includes all emotional, social and physical aspects of the individual's life. In health care, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is an assessment of how the individual's well-being may be affected over time by a disease, disability or disorder.[1][2]

Measurement

Early versions of healthcare-related quality of life measures referred to simple assessments of physical abilities by an external rater (for example, the patient is able to get up, eat and drink, and take care of personal hygiene without any help from others) or even to a single measurement (for example, the angle to which a limb could be flexed).

The current concept of health-related quality of life acknowledges that subjects put their actual situation in relation to their personal expectation.[3] The latter can vary over time, and react to external influences such as length and severity of illness, family support, etc. As with any situation involving multiple perspectives, patients' and physicians' rating of the same objective situation have been found to differ significantly. Consequently, health-related quality of life is now usually assessed using patient questionnaires. These are often multidimensional and cover physical, social, emotional, cognitive, work- or role-related, and possibly spiritual aspects as well as a wide variety of disease related symptoms, therapy induced side effects, and even the financial impact of medical conditions.[4] Although often used interchangeably with the measurement of health status, both health-related quality of life and health status measure different concepts.

Activities of daily living

Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) are activities that are oriented toward taking care of one's own body and are completed daily. These include bathing/showering, toileting and toilet hygiene, dressing, eating, functional mobility, personal hygiene and grooming, and sexual activity.[5] Many studies demonstrate the connection between ADLs and health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Mostly, findings show that difficulties in performing ADLs are directly or indirectly associated with decreased HRQOL. Furthermore, some studies found a graded relationship between ADL difficulties/disabilities and HRQOL- the less independent people are at ADLs- the lower their HRQOL is.[6][7] While ADLs are an excellent tool to objectively measure quality of life, it is important to remember that Quality of life goes beyond these activities. For more information about the complex concept of quality of life, see information regarding the disability paradox.[8]

In addition to ADLs, instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) can be used as a relatively objective measure of health-related quality of life. IADLs, as defined by the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), are “Activities to support daily life within the home and community that often require more complex interactions than those used in ADLs”.[5] IADLs include tasks such as: care for others, communication management, community mobility, financial management, health management, and home management. Activities of IADLS includes: grocery shopping, preparing food, housekeeping, using the phone, laundry, managing transportation/finances.[9] Research has found that an individual's ability to engage in IADLs can directly impact their quality of life.[10][11][12]

Pharmacology for older adults

Elderly patients taking more than five medications increases risk of cognitive impairment, and is one consideration when assessing what factors impact QoL, ADLs, and IADLs of older adults.[13] Due to multiple chronic conditions, managing medications in this group of people is particular challenging and complex.[14] Recent studies showed that polypharmacy is associated with ADL disability due to malnutrition,[15] and is a risk factor for hospital admission due to falls,[16] which can have severe consequences on a person's quality of life moving forward. Thus, when assessing an elderly person's quality of life, it is important to consider the medications an older patient is taking, and whether they are adhering to their current prescription taking schedule.[17]

Occupational Therapy's Role

Occupational therapists (OTs) are global healthcare professionals who treat individuals to achieve their highest level of quality of life and independence through participation in everyday activities. OTs are trained to complete a person-centered evaluation of an individual's interests and needs, and tailor their treatment to specifically address ADLs and IADLs that their patient values. In the AOTAs most recent vision statement (2025) they explicitly state that OT as an inclusive profession works to maximize quality of life through the effective solution of participation in everyday living.[18] To learn more about occupational therapy, see the Wikipedia page dedicated to the profession.

Special Considerations in Palliative Care

HRQoL in patients with serious, progressive, life-threatening illness should be given special considerations in both the measurement and analysis of HRQoL. Oftentimes, as level of functioning deteriorates, more emphasis is put on caregiver and proxy questionnaires or abbreviated questionnaires.[19] Additionally, as diseases progress, patients and families often shift their priorities throughout the disease course. This can affect the measurement of HRQoL as, oftentimes, patients change the way they respond to questionnaires which results in HRQoL staying the same of even improving as their physical condition worsens.[20] To address this issue, researchers have developed new instruments for measuring end-of-life HRQoL that incorporate factors such as sense of completion, relations with the healthcare system, preparation, symptom severity, and affective social support.[21] Additionally, research is being conducted on the impact of existential QoL on palliative care patients as terminal illness awareness and symptom burden may be associated with lower existential QoL.[22]

Examples

Similar to other psychometric assessment tools, health-related quality of life questionnaires should meet certain quality criteria, most importantly with regard to their reliability and validity. Hundreds of validated health-related quality of life questionnaires have been developed, some of which are specific to various illnesses. The questionnaires can be generalized into two categories:

Generic instruments

- CDC HRQOL–14 "Healthy Days Measure": A questionnaire with four base questions and ten optional questions used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/hrqol14_measure.htm).

- Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36, SF-12, SF-8): One example of a widely used questionnaire assessing physical and mental health-related quality of life. Used in clinical trials and population health assessments. Suitable for pharmacoeconomic analysis, benefiting healthcare rationing.

- EQ-5D a simple quality of life questionnaire (https://euroqol.org).

- AQoL-8D a comprehensive questionnaire [23][24] that assesses HR-QoL over 8 domains - independent living, happiness, mental health, coping, relationships, self-worth, pain, senses (https://www.aqol.com.au).

Disease, disorder or condition specific instruments

- King's Health Questionnaire (KHQ)

- International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) in urinary incontinence,[25] the LC -13 Lung Cancer module from the EORTC Quality of Life questionnaire library, or the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) ).

- Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life: 16-item questionnaire for use in psychiatric populations.

- ECOG, most commonly used to evaluate the impact of cancer on people.

- NYHA scale, most commonly used to evaluate the impact of heart disease on individuals.

- EORTC measurement system for use in clinical trials in oncology.[26] These tools are robustly tested and validated[27] and translated.[28] A large amount of reference data is now available.[29] The field of HRQOL has grown significantly in the last decade, with hundreds of new studies and better reporting of clinical trials.[30] HRQOL appears to be prognostic for survival in some diseases and patients.[31][32]

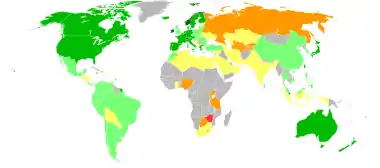

- WHO-Quality of life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF): A general Quality of life survey validated for several countries.[33]

- The Stroke Specific Quality Of Life scale SS-QOL: It is a patient-centered outcome measure intended to provide an assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) specific to patients with stroke only. It measures energy, family roles, language, mobility, mood, personality, self care, social roles, thinking, upper extremity function, vision and work productivity.[34]

- In rheumatology, condition specific instruments have been developed such as RAQoL[35] for rheumatoid arthritis, OAQoL[36] for osteoarthritis, ASQoL[37] for ankylosing spondylitis, SScQoL[38] for systemic sclerosis and PsAQoL[39] for people with psoriatic arthritis.

- MOS-HIV(Medical Outcome Survey-HIV) was developed specifically for people living with HIV/AIDS.[40]

Utility

A variety of validated surveys exist for healthcare providers to use for measuring a patient's health-related quality of life. The results are then used to help determine treatment options for the patient based on past results from other patients,[41] and to measure intra-individual improvements in QoL pre- and post-treatment.

When it is used as a longitudinal study device that surveys patients before, during, and after treatment, it can help health care providers determine which treatment plan is the best option, thereby improving healthcare through an evolutionary process.

Importance

There is a growing field of research concerned with developing, evaluating, and applying quality of life measures within health related research (e.g. within randomized controlled studies), especially in relation to Health Services Research. Well-executed health-related quality of life research informs those tasked with health rationing or anyone involved in the decision-making process of agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency[42] or National Institute for Clinical Excellence.[43] Additionally, health-related quality of life research may be used as the final step in clinical trials of experimental therapies.

The understanding of Quality of Life is recognized as an increasingly important healthcare topic because the relationship between cost and value raises complex problems, often with high emotional attachment because of the potential impact on human life. For instance, healthcare providers must refer to cost-benefit analysis to make economic decisions about access to expensive drugs that may prolong life by a short amount of time and/or provide a minimal increase to quality of life. Additionally, these treatment drugs must be weighed against the cost of alternative treatments or preventative medicine. In the case of chronic and/or terminal illness where no effective cure is available, an emphasis is placed on improving health-related quality of life through interventions such as symptom management,[44] adaptive technology, and palliative care. Another example of why understanding quality of life is important is during a randomized study of 151 patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer who were split into obtaining early palliative and standardized care group. The earlier palliative group not only had better quality of life based on the Functional assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung scale and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, but the palliative care group also had less depressive symptoms (16% vs. 38%, P=0.01) despite having received less aggressive end-of-life care (33% vs. 54%, P=0.05) and longer median overall survival than the standard group (11.6 months vs. 8.9 months, P=0.02). [45] By having a quality of life measure, we are able to evaluate early palliative care and see its value in terms of improving quality of care, reduced aggressive treatment and consequently costs, and also greater quality/quantity of life.

In the realm of elder care, research indicates that improvements in quality of life ratings may also improve resident outcomes, which can lead to substantial cost savings over time. Research has shown that evaluating an elderly person's functional status, in addition to other aspects of their health, helps improve geriatric quality of life and decrease caregiver burden.[46] Research has also shown that quality of life ratings can be successfully used as a key-performance metric when designing and implementing organizational change initiatives in nursing homes.[47]

Research

Research revolving around Health Related Quality of Life is extremely important because of the implications that it can have on current and future treatments and health protocols. Thereby, validated health-related quality of life questionnaires can become an integral part of clinical trials in determining the trial drugs' value in a cost-benefit analysis. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is using their health-related quality of life survey, Healthy Day Measure, as part of research to identify health disparities, track population trends, and build broad coalitions around a measure of population health. This information can then be used by multiple levels of government or other officials to "increase quality and years of life" and to "eliminate health disparities" for equal opportunity. [48]

Ethics

The quality of life ethic refers to an ethical principle that uses assessments of the quality of life that a person could potentially experience as a foundation for making decisions about the continuation or termination of life. It is often used in contrast to or in opposition to the sanctity of life ethic.

While measuring tools can be a way to scientifically quantify quality of life in an objective manner on a broad range of topics and circumstances, there are limitations and potential negative consequences with its utilization. Firstly, it makes the assumption that an assessment can be able to quantify domains such as physical, emotional, social, well-being, etc. with a single quantitative score. Furthermore, how are these domains weighted? Will they be measured the same or equally for each person? Or will it take into account how important these specific domains are for each person when creating the final score? Each person has their own specific set of experiences and values and a point of argument is that this needs to be taken into account. However, this would be a difficult task for the person to rank these quality of life domains. Another point to keep in mind is that people's values and experiences change over time and their quality of life domain rankings may differ. This caveat must be added or the dynamics of this could be taken into account when interpreting and understanding the results from a quality of life measuring tool. Quality of life measuring tools can also promote a negative and pessimistic view for clinicians, patients, and families, especially when used at baseline during the time of diagnosis. Quality of life measuring tools can fail to account for effective therapeutic strategies that can alleviate health burdens, and thus can promote a self-fulfilling prophecy for patients. On a societal level, the concept of low quality of life can also perpetuate negative prejudices experienced by people with disabilities or chronic illnesses.[49]

Analysis

Statistical biases

It is not considered uncommon for there to be some statistical anomalies during data analysis. Some of the more frequently seen in health-related quality of life analysis are the ceiling effect, the floor effect, and response shift bias.

The ceiling effect refers to how patients who start with a higher quality of life than the average patient do not have much room for improvement when treated. The opposite of this is the floor effect, where patients with a lower quality of life average have much more room for improvement.[3] Consequentially, if the spectrum of quality of life before treatment is too unbalanced, there is a greater potential for skewing the end results, creating the possibility for incorrectly portraying a treatment's effectiveness or lack thereof.

Response shift bias

Response shift bias is an increasing problem within longitudinal studies that rely on patient reported outcomes.[50] It refers to the potential of a subject's views, values, or expectations changing over the course of a study, thereby adding another factor of change on the end results. Clinicians and healthcare providers must recalibrate surveys over the course of a study to account for Response Shift Bias.[51] The degree of recalibration varies due to factors based on the individual area of investigation and length of study.

Statistical variation

In a study by Norman et al. about health-related quality of life surveys, it was found that most survey results were within a half standard deviation. Norman et al. theorized that this is due to the limited human discrimination ability as identified by George A. Miller in 1956. Utilizing the Magic Number of 7 ± 2, Miller theorized that when the scale on a survey extends beyond 7 ± 2, humans fail to be consistent and lose ability to differentiate individual steps on the scale because of channel capacity.

Norman et al. proposed health-related quality of life surveys use a half standard deviation as the statistically significant benefit of a treatment instead of calculating survey-specific "minimally important differences", which are the supposed real-life improvements reported by the subjects.[52] In other words, Norman et al. proposed all health-related quality of life survey scales be set to a half standard deviation instead of calculating a scale for each survey validation study where the steps are referred to as "minimally important differences".

References

- CDC - Concept - Health-Related Quality of Life

- Bottomley A (April 2002). "The cancer patient and quality of life". The Oncologist. 7 (2): 120–5. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.7-2-120. PMID 11961195. S2CID 20903110.

- Jongen PJ, Lehnick D, Sanders E, Seeldrayers P, Fredrikson S, Andersson M, Speck J (November 2010). "Health-related quality of life in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patients during treatment with glatiramer acetate: a prospective, observational, international, multi-centre study". Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 8: 133. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-8-133. PMC 2999586. PMID 21078142.

- Burckhardt CS, Anderson KL (October 2003). "The Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): reliability, validity, and utilization". Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 1: 60. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-60. PMC 269997. PMID 14613562.

- "Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process—Fourth Edition". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 74 (Supplement_2): 7412410010p1–7412410010p87. 2020-08-31. doi:10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001. ISSN 0272-9490. PMID 34780625. S2CID 204057541.

- Lyu, Wei; Wolinsky, Fredric D. (December 2017). "The Onset of ADL Difficulties and Changes in Health-Related Quality of Life". Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 15 (1): 217. doi:10.1186/s12955-017-0792-8. ISSN 1477-7525. PMC 5674843. PMID 29110672. S2CID 4242868.

- Medhi, GajendraKumar; Sarma, Jogesh; Pala, Star; Bhattacharya, Himashree; Bora, ParashJyoti; Visi, Vizovonuo (2019). "Association between health related quality of life (HRQOL) and activity of daily living (ADL) among elderly in an urban setting of Assam, India". Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 8 (5): 1760–1764. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_270_19. ISSN 2249-4863. PMC 6559106. PMID 31198751.

- Weeks, J. (2020). Foundation Health Measure Report, Health-Related Quality of Life and Well-Being. 6.

- Edemekong, Peter F.; Bomgaars, Deb L.; Sukumaran, Sukesh; Schoo, Caroline (2022), "Activities of Daily Living", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29261878, retrieved 2022-09-12

- Dickerson, Anne E.; Reistetter, Timothy; Gaudy, Jennifer R. (September 2013). "The Perception of Meaningfulness and Performance of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living From the Perspectives of the Medically At-Risk Older Adults and Their Caregivers". Journal of Applied Gerontology. 32 (6): 749–764. doi:10.1177/0733464811432455. ISSN 0733-4648. PMID 25474797. S2CID 40685553.

- Johs-Artisensi, Jennifer L.; Hansen, Kevin E.; Olson, Douglas M. (May 2020). "Qualitative analyses of nursing home residents' quality of life from multiple stakeholders' perspectives". Quality of Life Research. 29 (5): 1229–1238. doi:10.1007/s11136-019-02395-3. ISSN 1573-2649. PMID 31898111. S2CID 209528308.

- Koyfman, Irina; Finnell, Deborah (January 2019). "A Call for Interfacing Measures of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Across the Transition of Care". Home Healthcare Now. 37 (1): 44–49. doi:10.1097/NHH.0000000000000715. ISSN 2374-4529. PMID 30608467. S2CID 58591030.

- Chippa, Venu; Roy, Kamalika (2022), "Geriatric Cognitive Decline and Polypharmacy", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 34662089, retrieved 2022-09-12

- Schenker, Yael; Park, Seo Young; Jeong, Kwonho; Pruskowski, Jennifer; Kavalieratos, Dio; Resick, Judith; Abernethy, Amy; Kutner, Jean S. (April 2019). "Associations Between Polypharmacy, Symptom Burden, and Quality of Life in Patients with Advanced, Life-Limiting Illness". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 34 (4): 559–566. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04837-7. ISSN 1525-1497. PMC 6445911. PMID 30719645.

- Nakamura, Tomiyo; Itoh, Takashi; Yabe, Aiko; Imai, Shoko; Nakamura, Yoshimi; Mizokami, Yasuko; Okouchi, Yuki; Ikeshita, Akito; Kominato, Hidenori (2021-08-27). "Polypharmacy is associated with malnutrition and activities of daily living disability among daycare facility users: A cross-sectional study". Medicine. 100 (34): e27073. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000027073. ISSN 1536-5964. PMC 8389954. PMID 34449506.

- Zaninotto, P.; Huang, Y. T.; Di Gessa, G.; Abell, J.; Lassale, C.; Steptoe, A. (2020-11-26). "Polypharmacy is a risk factor for hospital admission due to a fall: evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing". BMC Public Health. 20 (1): 1804. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09920-x. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 7690163. PMID 33243195.

- Wilder, Lisa Van (2022). "Polypharmacy and Health-Related Quality of Life/Psychological Distress Among Patients With Chronic Disease". Preventing Chronic Disease. 19: E50. doi:10.5888/pcd19.220062. ISSN 1545-1151. PMC 9390791. PMID 35980834.

- "About AOTA – Mission and Vision". www.aota.org. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- Yanez, B.; Pearman, T.; Lis, C. G.; Beaumont, J. L.; Cella, D. (April 2013). "The FACT-G7: a rapid version of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G) for monitoring symptoms and concerns in oncology practice and research". Annals of Oncology. 24 (4): 1073–1078. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds539. ISSN 1569-8041. PMID 23136235.

- Robbins, R. A.; Simmons, Z.; Bremer, B. A.; Walsh, S. M.; Fischer, S. (2001-02-27). "Quality of life in ALS is maintained as physical function declines". Neurology. 56 (4): 442–444. doi:10.1212/wnl.56.4.442. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 11222784. S2CID 23125487.

- Steinhauser, Karen E.; Bosworth, Hayden B.; Clipp, Elizabeth C.; McNeilly, Maya; Christakis, Nicholas A.; Parker, Joanna; Tulsky, James A. (December 2002). "Initial assessment of a new instrument to measure quality of life at the end of life". Journal of Palliative Medicine. 5 (6): 829–841. doi:10.1089/10966210260499014. ISSN 1096-6218. PMID 12685529.

- Rantanen, Petra; Chochinov, Harvey Max; Emanuel, Linda L.; Handzo, George; Wilkie, Diana J.; Yao, Yingwei; Fitchett, George (January 2022). "Existential Quality of Life and Associated Factors in Cancer Patients Receiving Palliative Care". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 63 (1): 61–70. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.07.016. ISSN 1873-6513. PMC 8766863. PMID 34332045.

- Richardson J, Iezzi A, Khan MA, Maxwell A (2014). "Validity and reliability of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument". The Patient. 7 (1): 85–96. doi:10.1007/s40271-013-0036-x. PMC 3929769. PMID 24271592.

- Maxwell A, Özmen M, Iezzi A, Richardson J (December 2016). "Deriving population norms for the AQoL-6D and AQoL-8D multi-attribute utility instruments from web-based data". Quality of Life Research. 25 (12): 3209–3219. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1337-z. PMID 27344318. S2CID 2153470.

- Hirakawa T, Suzuki S, Kato K, Gotoh M, Yoshikawa Y (August 2013). "Randomized controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle training with or without biofeedback for urinary incontinence". International Urogynecology Journal. 24 (8): 1347–54. doi:10.1007/s00192-012-2012-8. PMID 23306768. S2CID 19485395.

- Bottomley A, Flechtner H, Efficace F, Vanvoorden V, Coens C, Therasse P, Velikova G, Blazeby J, Greimel E (August 2005). "Health related quality of life outcomes in cancer clinical trials". European Journal of Cancer. 41 (12): 1697–709. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.007. PMID 16043345.

- Bottomley A, Flechtner H, Efficace F, Vanvoorden V, Coens C, Therasse P, Velikova G, Blazeby J, Greimel E (August 2005). "Health related quality of life outcomes in cancer clinical trials". European Journal of Cancer. 41 (12): 1697–709. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.007. PMID 16043345.

- Koller M, Kantzer V, Mear I, Zarzar K, Martin M, Greimel E, Bottomley A, Arnott M, Kuliś D (April 2012). "The process of reconciliation: evaluation of guidelines for translating quality-of-life questionnaires". Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 12 (2): 189–97. doi:10.1586/erp.11.102. PMID 22458620. S2CID 207222200.

- EORTC Quality of Life Group = (July 2008). EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values (PDF). Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Velikova, G.; Coens, C.; Efficace, F.; Greimel, E.; Groenvold, M.; Johnson, C.; Singer, S.; Van De Poll-Franse, L.; Young, T.; Bottomley, A. (2012). "Health-Related Quality of Life in EORTC clinical trials — 30 years of progress from methodological developments to making a real impact on oncology practice". European Journal of Cancer Supplements. 10: 141–149. doi:10.1016/S1359-6349(12)70023-X.

- Quinten C, Coens C, Mauer M, Comte S, Sprangers MA, Cleeland C, Osoba D, Bjordal K, Bottomley A (September 2009). "Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials". The Lancet. Oncology. 10 (9): 865–71. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70200-1. PMID 19695956.

- Weis J, Arraras JI, Conroy T, Efficace F, Fleissner C, Görög A, Hammerlid E, Holzner B, Jones L, Lanceley A, Singer S, Wirtz M, Flechtner H, Bottomley A (May 2013). "Development of an EORTC quality of life phase III module measuring cancer-related fatigue (EORTC QLQ-FA13)". Psycho-Oncology. 22 (5): 1002–7. doi:10.1002/pon.3092. PMID 22565359. S2CID 20563475.

- "WHO Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF)". WHO. Retrieved 4 May 2015..

- Silva SM, Corrêa FI, Faria CD, Corrêa JC (February 2015). "Psychometric properties of the stroke specific quality of life scale for the assessment of participation in stroke survivors using the rasch model: a preliminary study". Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 27 (2): 389–92. doi:10.1589/jpts.27.389. PMC 4339145. PMID 25729175.

- Whalley D, McKenna SP, de Jong Z, van der Heijde D (August 1997). "Quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis". British Journal of Rheumatology. 36 (8): 884–8. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/36.8.884. PMID 9291858.

- Keenan AM, McKenna SP, Doward LC, Conaghan PG, Emery P, Tennant A (June 2008). "Development and validation of a needs-based quality of life instrument for osteoarthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 59 (6): 841–8. doi:10.1002/art.23714. PMID 18512719.

- Doward LC, Spoorenberg A, Cook SA, Whalley D, Helliwell PS, Kay LJ, McKenna SP, Tennant A, van der Heijde D, Chamberlain MA (January 2003). "Development of the ASQoL: a quality of life instrument specific to ankylosing spondylitis". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 62 (1): 20–6. doi:10.1136/ard.62.1.20. PMC 1754293. PMID 12480664.

- Ndosi M, Alcacer-Pitarch B, Allanore Y, Del Galdo F, Frerix M, García-Díaz S, Hesselstrand R, Kendall C, Matucci-Cerinic M, Mueller-Ladner U, Sandqvist G, Torrente-Segarra V, Schmeiser T, Sierakowska M, Sierakowska J, Sierakowski S, Redmond A (February 2018). "Common measure of quality of life for people with systemic sclerosis across seven European countries: a cross-sectional study". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 77 (7): annrheumdis–2017–212412. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212412. PMC 6029637. PMID 29463517.

- McKenna SP, Doward LC, Whalley D, Tennant A, Emery P, Veale DJ (February 2004). "Development of the PsAQoL: a quality of life instrument specific to psoriatic arthritis". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 63 (2): 162–9. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.006296. PMC 1754880. PMID 14722205.

- Wu, A. W., Revicki, D. A., Jacobson, D., & Malitz, F. E. (1997). Evidence for reliability, validity and usefulness of the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV). Quality of life research, 6(6), 481-493.

- "Health Measures Quality of Life". www.healthypeople.gov. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Bottomley A, Jones D, Claassens L (February 2009). "Patient-reported outcomes: assessment and current perspectives of the guidelines of the Food and Drug Administration and the reflection paper of the European Medicines Agency". European Journal of Cancer. 45 (3): 347–53. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.032. PMID 19013787.

- Marquis P, Caron M, Emery MP, et al. (2011). "The Role of Health-Related Quality of Life Data in the Drug Approval Processes in the US and Europe: A Review of Guidance Documents and Authorizations of Medicinal Products from 2006 to 2010". Pharm Med. 25 (3): 147–60. doi:10.1007/bf03256856. S2CID 31174846.

- "Symptom management". NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. United States National Cancer Institute. 2011-02-02.

- Temel, Jennifer S.; Greer, Joseph A.; Muzikansky, Alona; Gallagher, Emily R.; Admane, Sonal; Jackson, Vicki A.; Dahlin, Constance M.; Blinderman, Craig D.; Jacobsen, Juliet; Pirl, William F.; Billings, J. Andrew; Lynch, Thomas J. (2010-08-19). "Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer". New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (8): 733–742. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 20818875. S2CID 1128078.

- Chen, Zhongyi; Ding, Zhaosheng; Chen, Caixia; Sun, Yangfan; Jiang, Yuyu; Liu, Fenglan; Wang, Shanshan (2021-06-21). "Effectiveness of comprehensive geriatric assessment intervention on quality of life, caregiver burden and length of hospital stay: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMC Geriatrics. 21 (1): 377. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02319-2. ISSN 1471-2318. PMC 8218512. PMID 34154560.

- Mitchell JM, Kemp BJ (March 2000). "Quality of life in assisted living homes: a multidimensional analysis". The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 55 (2): P117–27. doi:10.1093/geronb/55.2.P117. PMID 10794190.

- Testa MA, Nackley JF (1994). "Methods for quality-of-life studies". Annual Review of Public Health. 15: 535–59. doi:10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.002535. PMID 8054098.

- "What's Wrong with Quality of Life as a Clinical Tool?". AMA Journal of Ethics. 7 (2). 2005-02-01. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2005.7.2.pfor1-0502. ISSN 2376-6980.

- Ring L, Höfer S, Heuston F, Harris D, O'Boyle CA (September 2005). "Response shift masks the treatment impact on patient reported outcomes (PROs): the example of individual quality of life in edentulous patients". Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 3: 55. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-3-55. PMC 1236951. PMID 16146573.

- Wagner JA (June 2005). "Response shift and glycemic control in children with diabetes". Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 3: 38. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-3-38. PMC 1180844. PMID 15955236.

- Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW (May 2003). "Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation". Medical Care. 41 (5): 582–92. doi:10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. PMID 12719681. S2CID 9198927.

External links

- ProQolid (Patient-Reported Outcome & Quality of Life Instruments Database)

- Mapi Research Trust ("Non-profit organization involved in Patient-Centered Outcomes")

- PROLabels(Database on Patient-Reported Outcome claims in marketing authorizations)

- Quality-of-Life-Recorder (Project to bring QoL measurement to routine practice. Platform & library of electronic questionnaires, Shareware/Freeware)

- The International Society for Quality of Life

- Health and Quality of Life Outcomes

- The Healthcare Center. Better Health for Everyone