Heavy Press Program

The Heavy Press Program was a Cold War-era program of the United States Air Force to build the largest forging presses and extrusion presses in the world. These machines greatly enhanced the US defense industry's capacity to forge large complex components out of light alloys, such as magnesium and aluminum. The program began in 1950 and concluded in 1957 after construction of four forging presses and six extruders, at an overall cost of $279 million. Eight of them are still in operation today, manufacturing structural parts for military and commercial aircraft. They still hold the records for size in North America, though they have since been surpassed by presses in Japan, France, Russia and China.[1][2]

The program produced ten machines, listed below.

Background

The Heavy Press Program was motivated by experiences from World War II. Nazi Germany held the largest heavy die forging presses during the war, and translated this advantage into high performance jet fighters. Because of the shortage of aluminum, German aircraft manufacturers used forged magnesium structural components, formed to shape in closed-die hydraulic presses. The Soviet Union captured the largest German press to survive the war, with a capacity of 33,000 ton, and were suspected to have seized the designs for an even larger 55,000 ton press. The next two largest units were captured by the United States and brought across the Atlantic Ocean, but they were half the size at 16,500 ton. As Cold War fears developed, American strategists worried that this would give the Soviet Air Force a crucial advantage and designed the Heavy Press Program to help win the arms race.[3][4][5]

Seventeen presses were originally planned with an expected cost of $389 million, but the project was scaled back to 10 presses in 1953.[6]

Air Force Lieutenant General K. B. Wolfe was the primary advocate for the Heavy Press Program. Alexander Zeitlin was another prominent figure of the program.

Presses

| Capacity (short tons) | Type of press | Built by | Operated by | Location | Began Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13,200 | extrusion | Alcoa | Lafayette, Indiana | 1953[9] | |

| 50,000 | forging | Mesta Machinery | Alcoa | Air Force Plant 47, 1600 Harvard Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio | May 5, 1955 |

| 35,000 | forging | United Engineering | Alcoa | Air Force Plant 47, 1600 Harvard Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio | 1955 |

| 8,000 | extrusion | Loewy Hydropress | Kaiser Aluminum | 1954 Halethorpe Farms Road, Halethorpe, Maryland | 1955 (Scrapped 2021 following facility closure by Arconic) |

| 8,000 | extrusion | Loewy Hydropress | Kaiser Aluminum | 1954 Halethorpe Farms Road, Halethorpe, Maryland | 1955 (Scrapped 2021 following facility closure by Arconic) |

| 8,000 | extrusion | Loewy Hydropress | Harvey Machine Co. | Torrance, California | May 1946(Scrapped 1992[10]) |

| 12,000 | extrusion | Lombard Corporation | Harvey Machine Co. | Torrance, California | August 1957[11] (Scrapped 1990s.[11]) |

| 50,000 | forging | Loewy Hydropress | Wyman-Gordon | Air Force Plant 63, Grafton, Massachusetts | October 1955[3]: 5 |

| 35,000 | forging | Loewy Hydropress | Wyman-Gordon | Air Force Plant 63, Grafton, Massachusetts | February 1955[3]: 5 |

| 12,000 | extrusion | Loewy Hydropress | Curtiss-Wright | Buffalo, New York |

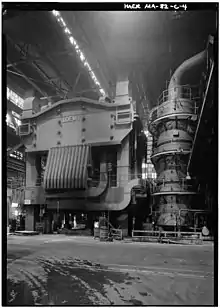

Landmark designation

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers designated the 50,000-ton Alcoa and Wyman-Gordon presses as Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmarks. The Alcoa press weighs 8,000 tons and is 87 feet (27 meters) tall. The die table is 26 by 12 feet (7.9 by 3.7 meters), and the maximum stroke is 6 feet (1.8 meters).[12]

External Links

- United States Air Force (1956). The Air Force Heavy Press Program. YouTube. Retrieved 2021-02-07.

References

- Heffernan, Tim (8 February 2012). "Iron Giant". The Atlantic. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- "China Building World's Largest Press Forge". China Tech Gadget. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 2015-02-10. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- "The Wyman-Gordon 50,000-ton Forging Press" (PDF). American Society of Mechanical Engineers. 20 October 1983. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- 50,000 Ton Closed Die Forging Press (PDF). American Society of Mechanical Engineers. 1981. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2012-02-12. History of the Mesta Press at Alcoa

- Edson, Peter (18 April 1952). "Revolutionary Metal Press Cuts Cost of Planes and Guns". Sarasota Journal. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- Pearson, Drew (11 September 1953). "Aircraft Presses Cut Back Here as Soviet Forges Ahead". The Free Lance-Star. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- Blue, D.D.; Kurtz, H.F. (1956). "Aluminum". Minerals yearbook metals and minerals (except fuels) 1953. Vol. I. Bureau of Mines, United States Government Printing Office. pp. 143–163, see p. 145. ISSN 0076-8952.

- Kurtz, H.F.; Heindl, R.A.; Wampler, C.I. (1958). "Aluminum". Minerals yearbook metals and minerals (except fuels) 1954. Vol. I. Bureau of Mines, United States Government Printing Office. pp. 133–157, see p. 135. ISSN 0076-8952.

- "Alcoa Gets Big Extrusion Press". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 31 January 1952. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- Sam, Gnerre. "Harvey Aluminum in Harbor Gateway had a long, sometimes turbulent history". Dailybreeze.com. Daily Breeze.

- Tim Heffernan. "The machines that made the Jet Age". Boing Boing. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- Buorgloner, Robert (1988). Historic American Engineering Record, Alcoa Forging Division: Mesta 50,000-Ton Closed Die Forging Press, Written Historical and Descriptive Data. National Park Services.