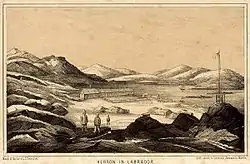

Hebron, Newfoundland and Labrador

Hebron was a Moravian mission and the northernmost settlement in Labrador. Founded in 1831, the mission disbanded in 1959. The Inuk Abraham Ulrikab and his family, exhibited in human zoos in Europe in 1880, were from Hebron.[1][2]

Climate

The site has an unusual sub-type of arctic (tundra) climate, characterized by relatively high average annual precipitation 798 mm (31.4 in) with half the precipitation occurring during the six coldest months (51% of the total falling from October through March). January, for example, averages -21 °C (-6 °F) and has 81 mm (3.2 in) of water-equivalent precipitation on average, perhaps the most humid air at that temperature experienced anywhere on earth.

| Climate data for Hebron, Newfoundland and Labrador | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −21.1 (−6.0) |

−20.4 (−4.7) |

−15 (5) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−15 (5) |

−5.2 (22.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 81 (3.2) |

56 (2.2) |

79 (3.1) |

43 (1.7) |

47 (1.9) |

65 (2.6) |

84 (3.3) |

70 (2.8) |

81 (3.2) |

52 (2.0) |

63 (2.5) |

77 (3.0) |

798 (31.5) |

| Source 1: [3] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [4] | |||||||||||||

History

Moravians began establishing missions in Labrador in 1771. The first was located at Nain. The Moravians sought to evangelize the Inuit in Labrador.

In 1831, the Moravian church established a mission at Hebron, a site located about 200 km (120 mi) north of Nain.

Life was hard at the settlement. Epidemics of whooping cough, influenza and smallpox ran through the community periodically. In 1918, Moravian missionaries brought an outbreak of Spanish influenza that devastated Hebron and Okak.[5] Approximately 86 of Hebron's 100 residents died.[6] The flu epidemic of 1918 was believed to have wiped out a third of the 1,200-member Inuit population of Labrador.[7]

Abandonment

In 1955, a member of the International Grenfell Association, an organization dedicated to the health and welfare of residents of Newfoundland and Labrador, wrote to the Government of Canada expressing concern about cramped living conditions at Hebron that had led to tuberculosis and a shortage of firewood.

After consultation with Moravian leaders, the decision was made to close the mission. The Inuit would be resettled into larger communities. "I see no other way than to suggest the Mission withdraw from Hebron this summer," said the Rev. Siegfried Hettasch.[8] By April 1959, there were 58 families at Hebron. The decision was announced at an Easter Monday service in 1959. There was no consultation with community members.

By the fall of that year, half of the families had moved on their own. The remainder left soon after the Grenfell nurse was withdrawn and the community store closed in the fall of 1959. The relocation broke up extended families to different communities. Some if not many were sent to communities where promised housing was not available.

A report written for the Canadian Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples said the relocation led to poverty for several of the Inuit. "They were put in places where they weren't familiar with the local environment so they didn't know where to hunt, fish or trap and aside from that, all of the best places were already claimed by people who originally lived in those communities," said the report's author, Carol Brice-Bennet.[8]

Aftermath

The site was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1976.[9] It is frequently visited by cruise ships.

The buildings of the original mission still stand. The main mission building has been undergoing renovation by Inuit volunteers and are in reasonably good condition considering the passage of time.

In 2005, Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Danny Williams apologized to Inuit affected by the relocations of Hebron and Nutak.[10][11][12] In August 2009, the provincial government unveiled a monument at the site of Hebron with an inscribed apology for the site closure.[13][14]

References

- "Abraham Ulrikab | the Canadian Encyclopedia".

- "Remains of Abraham Ulrikab may be returned to Labrador | CBC News".

- http://www.worldclimate.com/cgi-bin/data.pl?ref=N58W062+1202+0004500G2

- https://www.weatherbase.com/weather/weather.php3?s=719022&cityname=Hebron-Newfoundland-and-Labrador-Canada&units=metric

- "The Labrador pandemic of 1918". 20 March 2020.

- "The 1918 Spanish Flu".

- "Labrador History". HVBG.net; Them Days. Archived from the original on 2004-12-23.

- Green, Julie (September 3, 1998). "The dispossession of the Hebronimiut". Nunatsiaq.com. Happy Valley-Goose Bay. Archived from the original on 9 March 2001. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- Hebron Mission. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "Labrador's Inuit cheer land agreement". CBC news. January 22, 2005. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- "Inuit mark 50th anniversary of Labrador resettlement". CBC News. August 12, 2009. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- "Ceremony to mark forced relocation of Inuit village". CBC News. Aug 15, 2012. Retrieved Oct 16, 2020.

- "Memorial to Former Residents of Hebron Unveiled" (Press release). Executive Council, Labrador and Aboriginal Affairs, Tourism, Culture and Recreation. August 10, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- "Relocated Labrador Inuit to get apology monument". CBC News. July 24, 2009. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

External links

- Hebron Mission, National Historic Site of Canada

- History of Labrador

- The Inuit Archived 2005-12-01 at the Wayback Machine at Memorial University of Newfoundland

- Relocated Labrador Inuit to get apology monument, CBC News, 2009-07-24

- Monument unveiled to commemorate apology to Labrador Inuit, The Telegram, 2012-08-15

- Travelling back in time to Moravian Mission in Hebron, NTV, 2014-11-03

- Inventory of Moravian Mission Records at Dartmouth College Library

- William Whiteley Inventory of the Moravian Mission in Labrador at Dartmouth College Library