Dunnock

The dunnock (Prunella modularis) is a small passerine, or perching bird, found throughout temperate Europe and into Asian Russia. Dunnocks have also been successfully introduced into New Zealand. It is by far the most widespread member of the accentor family; most other accentors are limited to mountain habitats. Other common names of the dunnock include: hedge accentor, hedge sparrow or hedge warbler.

| Dunnock | |

|---|---|

_3.jpg.webp) | |

| Song recorded on Dartmoor in Devon, England | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Prunellidae |

| Genus: | Prunella |

| Species: | P. modularis |

| Binomial name | |

| Prunella modularis | |

| |

| Global range Year-Round Range Summer Range Winter Range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

The dunnock was described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae. He coined the binomial name of Motacilla modularis.[2] The specific epithet is from the Latin modularis "modulating" or "singing".[3] This species is now placed in the genus Prunella that was introduced by the French ornithologist Louis Vieillot in 1816.[4]

The name "dunnock" comes from the English dun (dingy brown, dark-coloured) and the diminutive ock,[5] and "accentor" is from post-classical Latin and means a person who sings with another.[6] The genus name Prunella is from the German Braunelle, "dunnock", a diminutive of braun, "brown".[7]

Eight subspecies are recognised:[8]

- P. m. hebridium Meinertzhagen, R, 1934 – Ireland and the Hebrides (west of Scotland)

- P. m. occidentalis (Hartert, 1910) – Scotland (except the Hebrides), England, Wales and west France

- P. m. modularis (Linnaeus, 1758) – north and central Europe

- P. m. mabbotti Harper, 1919 – Iberian Peninsula, south-central France and Italy

- P. m. meinertzhageni Harrison, JM & Pateff, 1937 – Balkans

- P. m. fuscata Mauersberger, 1971 – south Crimean Peninsula (north coast of the Black Sea)

- P. m. euxina Watson, 1961 – northwest and north Turkey

- P. m. obscura (Hablizl, 1783) – northeast Turkey, Caucasus and north Iran

Some taxonomists have recently suggested that dunnock might be better treated as three species, with P. m. mabbotti and P. m. obscura being elevated from subspecies status.[9]

Description

A robin-sized bird, the dunnock typically measures 13.5–14 cm (5.3–5.5 in) in length. It possesses a streaked back, somewhat resembling a small house sparrow. Like that species, the dunnock has a drab appearance which may have evolved to avoid predation. It is brownish underneath, and has a fine pointed bill. Adults have a grey head, and both sexes are similarly coloured.[10] Unlike any similar sized small brown bird, dunnocks exhibit frequent wing flicking, especially when engaged in territorial disputes or when competing for mating rights.[11] This gave rise to a common name of "shufflewing".[12]

The main call of the dunnock is a shrill, persistent tseep along with a high trilling note, which betrays the bird's otherwise inconspicuous presence. The song is rapid, thin and tinkling, a sweet warble which can be confused with that of the Eurasian wren, but is shorter and weaker.[13]

Distribution and habitat

Dunnocks are native to large areas of Eurasia, inhabiting much of Europe including Lebanon, northern Iran, and the Caucasus. They are the only commonly found accentor in lowland areas; all the others inhabit upland areas.[14] Dunnocks were successfully introduced into New Zealand during the 19th century, and are now widely distributed around the country and some offshore islands.[15][16] Favoured habitats include woodlands, shrubs, gardens, and hedgerows where they typically feed on the ground, often seeking out detritivores as food.[17]

Territoriality

Dunnocks are territorial and may engage in conflict with other birds that encroach upon their nests.[17] Males sometimes share a territory and exhibit a strict dominance hierarchy. Nevertheless, this social dominance is not translated into benefits to the alpha male in terms of reproduction, since paternity is usually equally shared between males of the group.[18][19] Furthermore, members of a group are rarely related, and so competition can result.[20]

Female territorial ranges are almost always exclusive. However, sometimes, multiple males will co-operate to defend a single territory containing multiple females. Males exhibit a strong dominance hierarchy within groups: older birds tend to be the dominant males and first-year birds are usually sub-dominant. Studies have found that close male relatives almost never share a territory.[20]

The male's ability to access females generally depends on female range size, which is affected by the distribution of food. When resources are distributed in dense patches, female ranges tend to be small and easy for males to monopolise. Subsequent mating systems, as discussed below, reflect high reproductive success for males and relatively lower success for females. In times of scarcity, female territories expand to accommodate the lack of resources, causing males to have a more difficult time monopolising females. Hence, females gain a reproductive advantage over males in this case.[20][21]

Breeding

Mating systems

.jpg.webp)

The dunnock possesses variable mating systems. Females are often polyandrous, breeding with two or more males at once,[22][23] which is quite rare among birds. This multiple mating system leads to the development of sperm competition amongst the male suitors. DNA fingerprinting has shown that chicks within a brood often have different fathers, depending on the success of the males at monopolising the female.[19] Males try to ensure their paternity by pecking at the cloaca[24] of the female to stimulate ejection of rival males' sperm.[25] Dunnocks take just one-tenth of a second to copulate and can mate more than 100 times a day.[26] Males provide parental care in proportion to their mating success, so two males and a female can commonly be seen provisioning nestlings at one nest.

Other mating systems also exist within dunnock populations, depending on the ratio of male to females and the overlap of territories. When only one female and one male territory overlap, monogamy is preferred. Sometimes, two or three adjacent female territories overlap one male territory, and so polygyny is favoured, with the male monopolising several females. Polygynandry also exists, in which two males jointly defend a territory containing several females. Polyandry, though, is the most common mating system of dunnocks found in nature. Depending on the population, males generally have the best reproductive success in polygynous populations, while females have the advantage during polyandry.[20][21]

Studies have illustrated the fluidity of dunnock mating systems. When given food in abundance, female territory size is reduced drastically. Consequently, males can more easily monopolise the females. Thus, the mating system can be shifted from one that favours female success (polyandry), to one that promotes male success (monogamy, polygynandry, or polygyny).[27]

Nest

_Nest_11.04.11.jpg.webp)

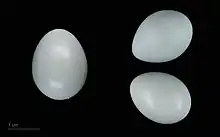

The dunnock builds a nest (predominantly from twigs and moss and lined with soft materials such as wool or feathers), low in a bush or conifer, where adults typically lay three to five unspotted blue eggs.[17]

Parental care and provisioning

Broods, depending on the population, can be raised by a lone female, multiple females with the part-time help of a male, multiple females with full-time help by a male, or by multiple females and multiple males. In pairs, the male and the female invest parental care at similar rates. However, in trios, the female and alpha male invest more care in chicks than does the beta male. In territories in which females are able to escape from males, both the alpha and beta males share provisioning equally. This last system represents the best case scenario for females, as it helps to ensure maximal care and the success of the young.

A study has found that males tend to not discriminate between their own young and those of another male in polyandrous or polygynandrous systems. However, they do vary their feeding depending on the certainty of paternity. If a male has greater access to a female, and therefore a higher chance of a successful fertilisation, during a specific mating period, it would provide more care towards the young.[27]

References

- BirdLife International (2018). "Prunella modularis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22718651A132118966. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22718651A132118966.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae:Laurentii Salvii. p. 184.

- Jobling, J.A. (2019). del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.; Christie, D.A.; de Juana, E. (eds.). "Key to Scientific Names in Ornithology". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Vieillot, Louis Jean Pierre (1816). Analyse d'une Nouvelle Ornithologie Élémentaire (in French). Paris: Deterville/self. p. 43.

- "Dunnock". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "Accentor". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, United Kingdom: Christopher Helm. p. 318. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Waxbills, parrotfinches, munias, whydahs, Olive Warbler, accentors, pipits". World Bird List Version 9.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- Pavia, Marco; Drovetski, Sergei V.; Boano, Giovanni; Conway, Kevin W.; Pellegrino, Irene; Voelker, Gary (15 June 2021). "Elevation of two subspecies of Dunnock Prunella modularis to species rank". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 141 (2): 199-210. doi:10.25226/bboc.v141i2.2021.a10.

- Heather, Barrie; Rogertson, Hugh (2005). The Field Guide to the Birds of New Zealand (Revised ed.). Viking Press.

- "Dunnock". RSPB. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary. G. & C. Merriam. 1913. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- Peterson, Roger; Mountfort, Guy; Hollom, P.A.D. (1954). A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. London: Collins.

- "Dunnock". British Garden Birds. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- "Dunnock | New Zealand Birds Online". www.nzbirdsonline.org.nz. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- Santos, Eduardo (2012). "Discovery of previously unknown historical records on the introduction of dunnocks (Prunella modularis) into Otago, New Zealand during the 19th century" (PDF). Notornis. 59 (1): 79–81.

- Montgomery, Sy. "Dunnock". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- Burke, T.; Davies, N.B.; Bruford, M.W.; Hatchwell, B.J. (1989). "Parental care and mating behaviour of polyandrous dunnocks Prunella modularis related to paternity by DNA fingerprinting". Nature. 338 (6212): 249–251. Bibcode:1989Natur.338..249B. doi:10.1038/338249a0. S2CID 4333938.

- Santos, Eduardo S. A.; Santos, Luana L. S.; Lagisz, Malgorzata; Nakagawa, Shinichi (2015). "Conflict and co-operation over sex: the consequences of social and genetic polyandry for reproductive success in dunnocks". Journal of Animal Ecology. 84 (6): 1509–1519. doi:10.1111/1365-2656.12432. ISSN 1365-2656. PMID 26257043.

- Davies, N. B.; Hartley, I.R. (1996). "Food patchiness, territory overlap and social systems: an experiment with dunnocks Prunella modularis". Journal of Animal Ecology. 65 (6): 837–846. doi:10.2307/5681. JSTOR 5681.

- Davies, N.B.; Houston, A.I. (1986). "Reproductive success of dunnocks, Prunella modularis, in a variable mating system". Journal of Animal Ecology. 55 (1): 123–138. doi:10.2307/4697. JSTOR 4697.

- Davies, Nicholas (1992). Dunnock behaviour and social evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198546740.

- Santos, Eduardo S. A.; Nakagawa, Shinichi (9 July 2013). "Breeding Biology and Variable Mating System of a Population of Introduced Dunnocks (Prunella modularis) in New Zealand". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e69329. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...869329S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069329. PMC 3706400. PMID 23874945.

- Attenborough, D. 1998. p.215. The Life of Birds BBC ISBN 0563-38792-0

- Davies, N. B. (1983). "Polyandry, cloaca-pecking and sperm competition in dunnocks". Nature. 302 (5906): 334–336. Bibcode:1983Natur.302..334D. doi:10.1038/302334a0. S2CID 4260839.

- Birkhead, Tim (2012). Bird Sense.

- Davies, N.B.; Lundberg, A. (1984). "Food distribution and a variable mating system in the dunnock, Prunella modularis" (PDF). Journal of Animal Ecology. 53 (3): 895–912. doi:10.2307/4666. JSTOR 4666.

External links

- Xeno-canto: audio recordings of the dunnock

- Dunnock videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.0 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Feathers of dunnock (Prunella modularis) Archived 8 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine