Bosal

A bosal or bozal(/boʊˈsɑːl/, /boʊˈsæl/, or /ˈboʊsəl/) is a type of noseband used on the classic hackamore of the vaquero tradition. It is usually made of braided rawhide and is fitted to the horse in a manner that allows it to rest quietly until the rider uses the reins to give a signal. It acts upon the horse's nose and jaw. In the Mexican Charro tradition, the Bozal substituted for the serrated iron cavesson used in Spain. [1] [2] Though seen in both the "Texas" and the "California" cowboy traditions, it is most closely associated with the "California" style of western riding.[3] Sometimes the term bosal is used to describe the entire classic hackamore or jaquima. Technically, however, the term refers only to the noseband portion of the equipment.[4]

Bosals come in varying diameters and weights, allowing a more skilled horse to "graduate" into ever lighter equipment. Once a young horse is solidly trained with a bosal, a bit is added and the horse is gradually shifted from the hackamore to a bit.

Description

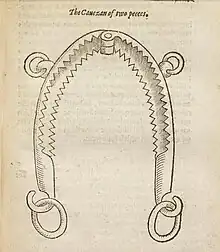

Over the horse's nose the bosal has a thick, stiff wrapper, called a "nose button." Beneath the horse's chin, the ends of the bosal are joined at a heavy heel knot. The bosal is carried on the animal's head by a headstall, sometimes called a "bosal hanger."[5]

The rein system of the hackamore is called the mecate. The mecate (/məˈkɑːti/ or /məˈkɑːteɪ/) is a long rope, traditionally of horsehair, approximately 20–25 feet long, tied to the bosal in a specialized manner that adjusts the fit of the bosal around the muzzle of the horse, and creates both a looped rein and a long free end that can be used for a number of purposes.[6] When a rider is mounted, the free end is coiled and attached to the saddle. When the rider is dismounted, the mecate is not used to tie the horse to a solid object, but rather is used as a lead rope and a form of longe line as needed.[3]

On a finished horse, a bosal with a properly balanced heel knot and mecate generally does not require additional support beyond the headstall. If needed, however, additional support can be provided by one or two accessories. The first is a throatlatch known as a fiador. If a fiador is used, a browband is added to hold the fiador to the headstall.[7] Less often, the bosal may be further supported by attaching the nose button to the horse's forelock or the crownpiece of the headstall, using a single thin strap of leather called a forelock hanger.[8]

Uses

Those who advocate use of the bosal-style hackamore note that many young horses' mouths are too sensitive for a bit because they are dealing with tooth eruption, replacing primary molars with permanent teeth. While designed for use on young horses, bosals are equipment intended for use by experienced trainers and should not be used by beginners, as they can be harsh in the wrong hands.

The bosal is ridden with two hands, and uses direct pressure, rather than leverage. It is particularly useful for encouraging flexion and softness in the young horse, though it has a design weakness that it is less useful than a snaffle bit for encouraging lateral flexion.

In the Mexican Charro tradition, the Charros would start a young horse, between four and five years old and typically wild, in a Bozal. This method of training horses was originally known in Mexico as “the Mesquital Method” because it was developed by the Charros of the Mezquital Valley in Central Mexico.[9] The Charros would teach the horse everything, absolutely everything, with the bozal, only introducing the bit much later after the horse had learned everything. The Charros had five stages for the horse:[10][11][12]

“Caballo Bronco”: the wild horse that has never been ridden.

“Caballo quebrantado”: the semi-broken horse.

“Caballo de falsa rienda” or “Caballo de una rienda”: the “false-rein horse” or “one-rein horse”, or the horse being ridden only with the bozal.

“Caballo de dos riendas”: the “two-rein horse”, or the horse being ridden with both the bozal and the bit.

“Caballo de rienda limpia” or “rienda pelona” or “caballo hecho”: the “made horse”, the horse being ridden only with the bit, the final stage of its education.

In the Charro tradition, the transition from the bozal into the bit was only a formality, as the horse had already been taught everything with the bozal. The bit only serves as a status symbol, rather then an actual need.

The classic vaquero and modern practitioners of the "California" cowboy tradition started a young horse in a bosal hackamore, then over time moved to ever-thinner and lighter bosals, then added a spade bit, then eventually transitioning to a spade alone, ridden with romal style reins, often retaining a light "bosalito" without a mecate. This process took many years and required an expert trainer.[3] The "Texas" tradition cowboy, and most modern trainers, will often start a young western riding horse in a bosal, but then move to a snaffle bit, then to a simple curb bit, and may never introduce the spade at all.[13] Other trainers start a horse with a snaffle bit, then once lateral flexion is achieved, move to a bosal to encourage flexion, then transition to a curb. However, this sequence is frowned upon by those who use classic vaquero techniques.

The combination of fiador with either a frentera or a standard headstall or hanger with browband stabilizes the bosal by supporting it with multiple attachment points. However, it also limits the action of the bosal, and thus, particularly in the California tradition, is removed once the horse is comfortable under saddle.[14] On a finished horse, a bosal with a properly balanced heel knot and mecate generally does not require these additions.

In the Texas tradition, where the bosal is placed low on the horse's face, as well as on very green horses in both the California vaquero and Texas traditions, the fiador is used to stabilize the bosal by attaching it to the headstall along the poll joint behind the ears, running under the jaw, and attaching to the bosal at the heel knot, along with the mecate.[15] In the California vaquero tradition, the fiador is omitted once the horse is able to work without it; in other traditions the fiador is retained.

Etymology

The word bosal is from the Spanish bosal [boˈsal], also spelled bozal [boˈθal], meaning muzzle.

See also

References

- García Icazbalceta, Joaquín (1899). Vocabulario de Mexicanismos. Mexico: La Europea. p. 58. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- Rincón Gallardo, Carlos (1938). El Libro del Charro Mexicano. Mexico: Imprenta Regis. pp. 5, 113. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- Price, Steven D. (ed.) The Whole Horse Catalog: Revised and Updated New York:Fireside 1998 ISBN 0-684-83995-4 p. 158-159

- Bennett, Deb (1998). Conquerors: The Roots of New World Horsemanship (1st ed.). Amigo Publications Inc. ISBN 0-9658533-0-6. Pages 54-55.

- Examples of bosal, hangers and modern mecate

- Connell, p. 1

- Williamson, pp.13-14

- Bennett, p. 61

- Revilla, Domingo (1844). El Museo Mexicano o Miscelánea de Amenidades Curiosas e Instructivas, Volume 3. Mexico: Ignacio Cumplido. p. 558. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- Laurent, Paul (1867). La guerre du Mexique de 1862 à 1866. Paris: Amyot. p. 288. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- Sánchez Navarro, Juan (1974). "ARTE DE AMANSAR Y ARRENDAR UN POTRO". Artes de México (174): 13–22. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- Sánchez Navarro, Juan; Icaza, Ernesto (1984). La Doma Mexicana el Arte de Arrendar un Caballo Criollo. Mexico: J. Sánchez Navarro. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- R.W.Miller

- Jaheil, Jessica. "Bosal, snaffle, spade - why?" Horse Sense, web page accessed August 19, 2007 Archived August 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- R.W.Miller, pp 127-134

- Bennett, Deb (1998) Conquerors: The Roots of New World Horsemanship. Amigo Publications Inc; 1st edition. ISBN 0-9658533-0-6

- Connell, Ed (1952) Hackamore Reinsman. The Longhorn Press, Cisco, Texas. Fifth Printing, August, 1958. (no ISBN in edition consulted; other editions ISBN 0-9648385-0-8)

- Miller, Robert W. (1974) Horse Behavior and Training. Big Sky Books, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT

- Williamson, Charles O. (1973) Breaking and Training the Stock Horse. Caxton Printers, Ltd., 6th edition (1st Ed., 1950). ISBN 0-9600144-1-1

- Segovia (1914)