Heibai Wuchang

The Heibai Wuchang, or Hak Bak Mo Seong, literally "Black and White Impermanence", are two Deities in Chinese folk religion in charge of escorting the spirits of the dead to the underworld. As their names suggest, they are dressed in black and white respectively. They are subordinates of Yanluo Wang, the Supreme Judge of the Underworld in Chinese mythology, alongside the Ox-Headed and Horse-Faced Hell Guards. They are worshiped as fortune deities and are also worshiped in Cheng Huang Temples in some countries.

| Heibai Wuchang | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 黑白無常 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黑白无常 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Black and White Impermanence | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Wuchang Gui | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 無常鬼 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 无常鬼 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Ghost of Impermanence | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

In some instances, the Heibai Wuchang are represented as a single being – instead of two separate beings – known as the Wuchang Gui (also romanised Wu-ch'ang Kuei), literally "Ghost of Impermanence". Depending on the person it encounters, the Wuchang Gui can appear as either a fortune deity who rewards the person for doing good deeds or a malevolent deity who punishes the person for committing evil.

Alternative names

In folklore, the White Guard's name is Xie Bi'an (謝必安; 谢必安; Xiè Bì'ān), which can be interpreted as "Those who make amends ("Xie") will always be at peace ("Bi'an")". The Black Guard's name is Fan Wujiu (范無咎; 范无咎; Fàn Wújiù), which conversely means that "Those who commit crimes ("Fan") will have no salvation ("Wujiu")". They are sometimes referred to as "Generals Fan and Xie" (范謝將軍; 范谢将军; Fàn Xiè Jiāngjūn).

In Fujian Province and among overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asian countries such as Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia, they are known as "First and Second Masters" (大二老爺; 大二老爷; Dà Èr Lǎoyé) or "First and Second Uncles" (大二爺伯; 大二爷伯; Dà Èr Yébó; Tua Di Ah Pek / Tua Li Ya Pek in Hokkien).

In Taiwan, they are called "Seventh and Eighth Masters" (七爺八爺; 七爷八爷; Qīyé Bāyé).

In Sichuan Province, they are referred to as the "Two Masters Wu" (吳二爺; 吴二爷; Wú Èr Yé).[1]

Iconography

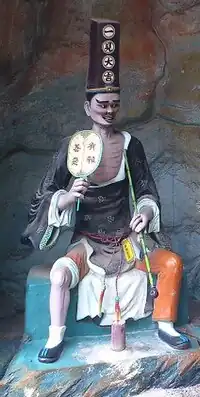

The White Guard is commonly portrayed as a fair complexioned man dressed in a white robe and wearing a tall hat bearing the Chinese words "Become Rich Upon Encountering Me" (一見發財 / 一見生財), "Become Lucky Upon Encountering Me" (一見大吉), or "You Have Come Too" (你也來了). He holds a hand fan in one hand and a fish-shaped shackle or wooden sign in the other hand. He is usually depicted as the taller of the duo.

The Black Guard is typically represented as a dark complexioned man dressed in a black robe and wearing a hat similar to the one worn by the White Guard. The Chinese words on his hat are "Peace to the World" (天下太平) or "Arresting You Right Now" (正在捉你). He holds a hand fan in one hand and a squarish wooden sign in the other hand. The sign bears the words "Making a Clear Distinction Between Good and Evil" (善惡分明) or "Rewarding the Good and Punishing the Evil" (獎善罰惡). A long chain is wrapped around one of his arms.

Some statues of them depict them with ferocious snarls on their faces and long red tongues sticking out their mouths to scare away evil spirits. However, sometimes they have different facial expressions: the White Guard looks friendly and approachable while the Black Guard looks stern and fierce.

Stories

One day, the White Guard was on patrol when he saw a woman and two children crying in front of a grave. He asked what happened. The woman was the daughter of a wealthy merchant, who owned four shops. She was born with smallpox, which affected her physical appearance. Her mother died in depression after feeling guilty for what happened to her daughter. The merchant had a cunning servant, who knew that no man would want to marry his master's daughter because of her appearance. The servant considered that if he married her, he would inherit his master's wealth when his master died, so he pretended to like his master's daughter and eventually married her. She had two children with him. The servant revealed his true colours later: He neglected his family, treated them with contempt, and spent his time indulging in sensual pleasures. The merchant regretted his decision to marry his daughter to his servant and died in frustration.

The White Guard felt angry after hearing the story and decided to help the woman. When she returned home, she met a man who wanted to collect a gambling debt owed by her husband. After she paid him, he saw that she was alone and tried to molest her but she shoved him away and locked herself inside her room. She then cried over her plight and tried to hang herself. Just then, the door opened and the White Guard came in with her children. She saw the White Guard's friendly appearance and felt no fear. He advised her, "Why are you thinking of taking your own life? Why don't you pack your belongings and leave this place for good with your children? They need you to take care of them and raise them." She heeded the White Guard's advice. After they left, the house and the four shops suddenly caught fire and were burnt down. By the time the servant found out about the fire, all his inherited fortune had already been destroyed.

Background stories

The most common background story of the Heibai Wuchang says that Xie Bi'an and Fan Wujiu used to work as constables in a yamen. One day, a convict they were escorting to another location escaped during the journey. They decided to split up and search for the escaped convict and meet again later under a bridge at a certain time. However, Xie Bi'an was delayed due to heavy rain so he did not reach the bridge in time. Fan Wujiu, who was on time, waited under the bridge. The heavy rain caused flooding in the area under the bridge. Fan Wujiu refused to leave because he wanted to keep his promise to his colleague, and eventually drowned. When Xie Bi'an arrived, he was saddened to see that Fan Wujiu had drowned, so he committed suicide by hanging himself. The Jade Emperor was deeply impressed by their friendship so he appointed them as "Guardians of the Underworld".

Some other versions of their background story are generally similar to the above story in two aspects. First, both of them agreed to meet at a certain place at a certain time. Second, the ways in which they died. The differences lie in their previous careers: Some believed they were military officers (hence they were also called "Generals") while others said they were peasants who lived next to each other.

There are other stories which say that the Heibai Wuchang have different, unrelated backgrounds. The Black Guard was a scoundrel who spent his time gambling. His father tried to discipline him and force him to change his ways but he refused to listen. One day, he lost all his money in gambling and had a violent argument with his father when he came home. His father lost control of himself and killed his son in anger. After his death, the Black Guard was sent to Hell, where he received due punishment. He repented and atoned for his sins by doing several good deeds. The gods were touched by his repentance and appointed him as the Black Guard of Impermanence. The White Guard, on the other hand, was born in a wealthy family and had a kind personality. His father once sent him on an errand with a large sum of money, but he forgot about his errand and used the money to help a poor family in need. When he realised his mistake, he felt ashamed to return home to face his parents so he committed suicide. After his death, the gods considered his good deeds and appointed him as the White Guard of Impermanence.

In popular culture

- The Nickelodeon cartoon Avatar: The Last Airbender features a giant panda spirit named Hei Bai, who takes one of the main characters into the spirit world.

- The 2016 mobile video game Onmyōji developed by NetEase, despite being set in Japan, features the deities as collectible and playable characters. They are portrayed as brothers and referred to using Japanese names Kuromujō and Shiromujō and exclusively in Chinese text as Guǐshǐ Hēi (鬼使黑) and Guǐshǐ Bái (鬼使白), and are voiced by Kazuya Nakai and Ken'ichi Suzumura respectively. The characters unique to this game Kurodōji and Shirodōji, portrayed as the apprentices to the aforementioned two, closely resemble them; they are voiced by Tomokazu Sugita and Yūichi Nakamura respectively.

- In the game Identity V by the same company, a pair of playable characters bears resemblance to the two deities and are very likely to be inspired by them. Incidentally, these two characters are called "Wu Chang" as their collective name, as well as their respective names being Xie Bi’an and Fan Wujiu.

- Statues of Heibai Wuchang are present in the Taiwanese game Detention.

- In the manga series Houseki no Kuni, the characters Diamond and Bort closely resemble the two deities, though it is unconfirmed if this was intentional.

- In the 2021 Chinese drama series Word of Honor, two of the martial-artist group "Ten Devils of Ghost Valley" are dressed and named after the black and white Wuchang, and the leader of the Devils is dressed and named after the composite Wuchang Gui.

- In the 2022 mobile game Dislyte as "Death guard Hei" and "Death guard Bai".

See also

- Yanluo Wang (閻羅王)

- Cheng Huang Gong (城隍公)

- Zhong Kui (鍾馗)

- Meng Po (孟婆)

- Ox-Head and Horse-Face Guards (牛頭馬面)

- Youdu (幽都)

- Chinese folk religion

- List of supernatural beings in Chinese folklore

References

- Wang, Wenhu; Zhang, Yizhou; Zhou, Jiayun (1987). 四川方言詞典 [Dictionary of the Sichuan Dialect] (in Chinese). Sichuan People's Publishing House.

- Xie, Chiyu (1985). 閩南移民的信仰舊俗 [Traditional Beliefs and Practices of Migrants from Fujian] (in Chinese).

- 新竹都城隍廟簡介 [Brief Introduction to the Temple of the City God in Hsinchu] (in Chinese). 2010.

- Lin, Meirong; Gu, Shenche, eds. (2013). 迎神在臺北:台北迎城隍、艋舺迎青山王、台北靈安社陣頭 [Welcoming Deities in Taipei] (in Chinese). Taipei: The Committee of Taipei Historical Records.

- Gu, Shenche (2014). 謝范將軍信仰與神將文化—以臺北市艋舺為中心 [Beliefs About Generals Xie and Fan and the Culture of Divine Generals - With Bangka, Taipei as the Centre]. 古典文獻與民俗藝術集刊 [Journal of Chinese Documentation and Folk Arts] (in Chinese). Taipei: Graduate Institute of Chinese Documentation and Folk Arts, National Taipei University. 3: 101–121.