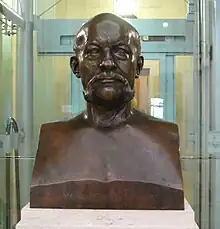

Rudolf von Gneist

Heinrich Rudolf Hermann Friedrich von Gneist (13 August 1816 – 22 July 1895) was a German jurist and politician. Born in Berlin, he was the son of a judge attached to the city's Kammergericht (Court of Appeal).[1] Gneist made significant influence on his student Max Weber[2] and also contributed to Japan's first constitution through his communication with Itō Hirobumi.

Rudolf von Gneist | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).png.webp) | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 August 1816 Berlin, Prussia |

| Died | 22 July 1895 (aged 78) Berlin, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | jurist, political scientist, politician |

Biography

After receiving his secondary education at the gymnasium at Eisleben in Prussian Saxony, Gneist entered the Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin in 1833 as a student of jurisprudence, and became a pupil of the famous Roman law teacher Savigny. Proceeding to the degree of doctor juris in 1838, young Gneist immediately established himself as a Privatdozent in the faculty of law. He had, however, already chosen the judicial branch of the legal profession as a career, and having while yet a student acted as Auscultator, was admitted Assessor in 1841.[1]

He soon found leisure and opportunity to fulfill a much-cherished wish, and spent the next few years on an extended tour of Italy, France and England. He used his "wanderjahre" ("journeyman's year") for the purposes of comparative study; upon on his return in 1844, he was appointed extraordinary professor of Roman law in the University of Berlin, and thus began a professorial connection which ended only with his death. The first fruits of his activity as a teacher were seen in his brilliant work, Die formellen Verträge des heutigen römischen Obligationen-Rechtes (Berlin, 1845). Pari passu with his academic labors he continued his judicial career, and became in due course successively assistant judge of the superior court and of the supreme tribunal. But to a mind constituted such as his, the want of elasticity in the procedure of the courts was galling. In the preface to his Englische Verfassungsgeschichte, Gneist writes that he was brought up "in the laborious and rigid school of Prussian judges, at a time when the duty of formulating the matter in litigation was entailed upon the judge who personally conducted the pleadings, I became acquainted both with the advantages possessed by the Prussian bureau system as also with its weak points." Feeling the necessity for fundamental reforms in legal procedure, he published, in 1849, his Trial by Jury, in which, after pointing out that the origin of that institution was common to both Germany and England, and showing in a masterly way the benefits which had accrued to the latter country through its more extended application, he pleaded for its freer admission in the tribunals of his own country.[1]

The period of storm and stress in 1848 afforded Gneist an opportunity for which he had yearned, and he threw himself with ardor into the constitutional struggles of Prussia. Although his candidature for election to the National Assembly of that year was unsuccessful, he felt that the die was cast, and, deciding upon a political career, retired from his judicial position in 1850. Entering the ranks of the National Liberal Party, he began both in writing and speeches actively to champion their cause, now busying himself pre-eminently with the study of constitutional law and history. In 1853 his Adel und Rittershaft was published in England, and in 1857 the Geschichte und heutige Gestalt der Ämter in England, a pamphlet primarily written to combat the Prussian abuses of government, but which the author also claimed had not been without its effect in modifying certain views that had until then ruled in England itself. In 1858 Gneist was appointed ordinary professor of Roman law.[1]

Also in 1858, he commenced his parliamentary career by his election for Stettin to the Prussian House of Representatives, in which assembly he sat thenceforward uninterruptedly until 1893. Joining the Left, he at once became one of its leading spokesmen. His chief oratorical triumphs are associated with the early period of his membership of the House; two noteworthy occasions being his violent attack (September 1862) upon the government budget in connection with the reorganization of the Prussian army, and his defense (1864) of the Polish chiefs of the Province of Posen, who were accused of high treason.[3]

He was a great admirer of the English constitution,[4] and during 1857 to 1863 published Das heutige englische Verfassungs- und Verwaltungsrecht (Contemporary English constitutional law and administration). This work aimed at exercising political pressure upon the government of the day by contrasting English and German constitutional law and administration.[5]

In 1868 Gneist became a member of the North German parliament, and acted as a member of the commission for organizing the federal army, and also of that for the settlement of controversial ecclesiastical questions. On the establishment of German unity his mandate was renewed for the Reichstag, and there he served as an active and prominent member of the National Liberal party, until 1884. In the Kulturkampf he sided with the government against the attacks of the Clericals, whom he bitterly denounced, and whose implacable enemy he ever showed himself. In 1879, together with his colleague, Hänel, he violently attacked the motion for the prosecution of certain socialist members, which as a result of the vigor of his opposition was almost unanimously rejected. He was parliamentary reporter for the committees on all great financial and administrative questions, and his profound acquaintance with constitutional law caused his advice to be frequently sought, not only in his own but also in other countries. In Prussia he greatly influenced legislation, the reform of the judicial and penal systems and the new constitution of the Evangelical Church being largely his work. In 1875, he was appointed a member of the supreme administrative court (Oberverwaltungsgericht) of Prussia, but only held office for two years.[5]

He was also consulted by the Japanese government when a constitution was being introduced into that country.[5] In 1882, Japanese Prime Minister of Japan Itō Hirobumi and a delegation from Japan visited Europe to study the government systems of various western nations. They met Gneist in Berlin, and he instructed them in constitutional law for a six-month period. The Constitution of the Empire of Japan reflects Gneist's conservatism in limiting the powers of the parliament, and strengthening those of the cabinet. His student, Albert Mosse, was later dispatched to Japan as a legal advisor to the Meiji government.

In 1882 was published his Englische Verfassungsgeschichte (trans. History of the English Constitution, London, 1886), which may perhaps be described as his magnum opus. It placed the author at once on the level of such writers on English constitutional history as Hallam and Stubbs, and supplied English jurisprudence with a text-book almost unrivalled in its of historical research. In 1888 one of the first acts of the ill-fated Friedrich III, German Emperor, who as crown prince had always shown great admiration for Gneist, was to ennoble him, and attach him as instructor in constitutional law to his son, Wilhelm II, German Emperor. The last years of his life were full of energy, and, in the possession of all his faculties, he continued his academic labors until a short time before his death.[5]

Perhaps it should not be said that Gneist's career as a politician was entirely successful. In a country where parliamentary institutions are the living exponents of the popular will he might have risen to a foremost position in the state; as it was, the party to which he allied himself could never hope to become more than what it remained, a parliamentary faction, and the influence it for a time wielded in the counsels of the state waned as soon as the Social-Democratic party grew to be a force to be reckoned with. It is as a writer and a teacher that Gneist is best known to posterity. He was a jurist of a special type: to him law was not mere theory, but a living force; and this conception of its power animates all his schemes of practical reform. As a teacher he exercised a magnetic influence, not only for the clearness and cogency of his exposition, but also because of the success with which he developed the talents and guided the aspirations of his pupils. He was a man of noble bearing, religious, and imbued with a stern sense of duty. He was proud of being a Junker, and throughout his writings, despite their liberal tendencies, may be perceived the loyalty and affection with which he clung to monarchical institutions.[5]

Works

Gneist was a prolific writer, especially on the subject he had made peculiarly his own, that of constitutional law and history, and among his works, other than those above named, may be mentioned the following:[5]

- Budget und Gesetz nach dem constitutionellen Staatsrecht Englands (Berlin, 1867)

- Freje Advocatur (Berlin, 1867)

- Die Eigenart des Preussischen Staats (1878)

- Der Rechtsstaat (Berlin, 1872, and 2nd edition, 1879)

- Zur Verwaltungsreform in Preussen (Leipzig, 1880)

- Das englische Parlament (Berlin, 1886); in English translation, The English Parliament (London, 1886; 3rd edition, 1889)

- Die Militärvorlage von 1892 und der preussische Verfassungsconflikt von 1862 bis 1866 (Berlin, 1893)

- Die nationale Rechtsidee von den Ständen und das preussische Dreiklassenwahlsystem (Berlin, 1895)

- Die verfassungsmassige Stellung des preussischen Gesamtministeriums (Berlin, 1895)

See O. Gierke, Rudolph von Gneist, Gedächtnisrede (Berlin, 1895), an In Memoriam address delivered in Berlin.

Notes

- Ashworth 1911, p. 150.

- Jacob Peter Mayer (1998). Max Weber and German Politics. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415174558.

- Ashworth 1911, pp. 150–151.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Ashworth 1911, p. 151.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ashworth, Philip Arthur (1911). "Gneist, Heinrich Rudolf Hermann Friedrich von". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–151.

External links

- Works by Rudolf Gneist at Open Library

- Conrad Bornhak, Rudolf von Gneist, JSTOR