Hantavirus hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome

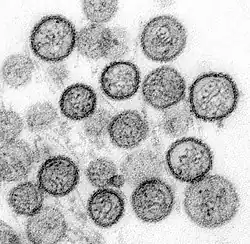

Hantavirus hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) is a group of clinically similar illnesses caused by species of hantaviruses. It is also known as Korean hemorrhagic fever and epidemic hemorrhagic fever. It is found in Europe, Asia, and Africa.[1] The species that cause HFRS include Hantaan orthohantavirus, Dobrava-Belgrade orthohantavirus, Saaremaa virus, Seoul orthohantavirus, Puumala orthohantavirus and other orthohantaviruses. Of these species, Hantaan River virus and Dobrava-Belgrade virus cause the most severe form of the syndrome and have the highest morbidity rates. When caused by the Puumala virus, it is also called nephropathia epidemica. This infection is known as sorkfeber (vole fever) in Swedish, myyräkuume (mole fever) in Finnish, and musepest (mouse plague) in Norwegian.

Both HFRS and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) are caused by hantaviruses, specifically when humans inhale aerosolized excrements of infected rodents. Both diseases appear to be immunopathologic, and inflammatory mediators are important in causing the clinical manifestations.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of HFRS usually develop within one to two weeks after exposure to infectious material, but in rare cases, they may take up to eight weeks to develop. In Nephropathia epidemica, the incubation period is three weeks. Initial symptoms begin suddenly and include intense headaches, back and abdominal pain, fever, chills, nausea, and blurred vision. Individuals may have flushing of the face, inflammation or redness of the eyes, or a rash. Later symptoms can include low blood pressure, acute shock, vascular leakage, and acute kidney failure, which can cause severe fluid overload.

The severity of the disease varies depending upon the virus causing the infection. Hantaan and Dobrava virus infections usually cause severe symptoms, while Seoul, Saaremaa, and Puumala virus infections are usually more moderate. Complete recovery can take weeks or months.[3]

The course of the illness can be split into five phases:

- Febrile phase

- Symptoms include redness of cheeks and nose, fever, chills, sweaty palms, diarrhea, malaise, headaches, nausea, abdominal and back pain, respiratory problems such as the ones common in the influenza virus, as well as gastro-intestinal problems. These symptoms normally occur for three to seven days and arise about two to three weeks after exposure.[4]

- Hypotensive phase

- This occurs when the blood platelet levels drop and symptoms can lead to tachycardia and hypoxemia. This phase can last for two days.

- Oliguric phase

- This phase lasts for three to seven days and is characterised by the onset of renal failure and proteinuria.

- Diuretic phase

- This is characterized by diuresis of three to six litres per day, which can last for a couple of days up to weeks.

- Convalescent phase

- This is normally when recovery occurs and symptoms begin to improve.

This syndrome can also be fatal. In some cases, it has been known to cause permanent renal failure.[5]

Transmission

Hantaviruses infect various rodents, generally without causing disease. Transmission by aerosolized rodent excreta still remains the only known way the virus is transmitted to humans. In general, droplet and/or fomite transfer has not been shown in the hantaviruses in either the pulmonary or hemorrhagic forms.[6][7]

For Nephropathia epidemica, the bank vole is the reservoir for the virus, which humans contract through inhalation of aerosolised vole droppings.[8]

Diagnosis

HFRS is difficult to diagnose on clinical grounds alone and serological evidence is often needed. A fourfold rise in IgG antibody titer in a one-week interval and the presence of the IgM type of antibodies against hantaviruses are good evidence for an acute hantavirus infection. HFRS should be suspected in patients with acute febrile flu-like illness, kidney failure of unknown origin and sometimes liver dysfunction.[9]

Prevention

Rodent control in and around the home remains the primary prevention strategy, as well as eliminating contact with rodents in the workplace and campsite. Closed storage sheds and cabins are often ideal sites for rodent infestations. Airing out of such spaces prior to use is recommended. Avoid direct contact with rodent droppings and wear a mask to avoid inhalation of aerosolized rodent secretions.[10]

Treatment

There is no cure for HFRS. Treatment involves supportive therapy including renal dialysis. Treatment with ribavirin in China and Korea, administered within seven days of onset of fever, resulted in a reduced mortality as well as shortened course of illness.[3][4]

Epidemiology

HFRS is primarily a Eurasian disease, whereas HPS appears to be confined to the Americas. The geography is directly related to the indigenous rodent hosts and the viruses that coevolved with them.[9]

Although fatal in a small percentage of cases, nephropathia epidemica is generally milder than the HFRS that is caused by hantaviruses in other parts of the world.[11]

In Popular Culture

HFRS was the subject of an episode of the television series M*A*S*H. In season 6, episode 6 the 4077th dealt with a condition, with similar symptoms to HFRS, called "Korean Hemorrhagic Fever".

See also

References

- Cosgriff TM, Lewis RM (December 1991). "Mechanisms of disease in hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome". Kidney Int. Suppl. 35: S72–9. PMID 1685203.

- Peters, Md; Simpson, Md, Phd, Mph, Gary L.; Levy, Md, Phd, H. (1999). "Spectrum of Hantavirus Infection: Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome and Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome1". Annual Review of Medicine. 50: 531–545. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.531. PMID 10073292.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lee HW, van der Groen G (1989). "Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome". Prog. Med. Virol. 36: 62–102. PMID 2573914.

- Muranyi, Walter; Bahr, Udo; Zeier, Martin; Van Der Woude, Fokko J. (2005). "Hantavirus Infection". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 16 (12): 3669–3679. doi:10.1681/ASN.2005050561. PMID 16267154.

- Kulzer P, Heidland A (December 1994). "[Acute kidney failure caused by Hantaviruses]". Ther Umsch (in German). 51 (12): 824–31. PMID 7784996.

- Peters CJ (2006). "Emerging infections: lessons from the viral hemorrhagic fevers". Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 117: 189–96, discussion 196–7. PMC 1500910. PMID 18528473.

- Crowley, J.; Crusberg, T. "Ebola and Marburg Virus Genomic Structure, Comparative and Molecular Biology". Dept. of Biology & Biotechnology, Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Archived from the original on 2013-10-15.

- Rose AM, Vapalahti O, Lyytikäinen O, Nuorti P (January 2003). "Patterns of Puumala virus infection in Finland". Euro Surveill. 8 (1): 9–13. doi:10.2807/esm.08.01.00394-en. PMID 12631978.

- Peters CJ, Simpson GL, Levy H (1999). "Spectrum of hantavirus infection: hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome". Annu. Rev. Med. 50: 531–45. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.531. PMID 10073292.

- "CDC - Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS) - Hantavirus". Cdc.gov. 2013-02-06. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Jonsson CB, Figueiredo LT, Vapalahti O (April 2010). "A global perspective on hantavirus ecology, epidemiology, and disease". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23 (2): 412–41. doi:10.1128/CMR.00062-09. PMC 2863364. PMID 20375360.

External links

- Sloan Science and Film / Short Films / Muerto Canyon by Jen Peel 29 minutes

- "Hantaviruses, with emphasis on Four Corners Hantavirus" by Brian Hjelle, M.D., Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, University of New Mexico

- CDC's Hantavirus Technical Information Index page

- Viralzone: Hantavirus

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Bunyaviridae

- Occurrences and deaths in North and South America

- Significant rise in number of Puumala virus cases in Southern Finland. Helsinki Sanomat Sep 29 2008.