Henry, Count of Portugal

Henry (Portuguese: Henrique, French: Henri; c. 1066 – 22 May 1112), Count of Portugal, was the first member of the Capetian House of Burgundy to rule Portugal and the father of the country's first king, Afonso Henriques.

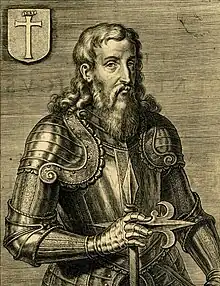

| Henry | |

|---|---|

Portrait in Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz's "Philippus Prudens", 1639 | |

| Count of Portugal | |

| Reign | 1096 – 1112 |

| Successor | Teresa and Afonso |

| Co-count | Teresa |

| Born | c. 1066 Dijon, Burgundy |

| Died | 22 May 1112 Astorga, León |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Teresa of León |

| Issue Detail | Afonso I of Portugal |

| House | Portuguese House of Burgundy (founder) |

| Father | Henry of Burgundy |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Biographical sketch

Family relations

Born in about 1066 in Dijon, Duchy of Burgundy, Count Henry was the youngest son of Henry, the second son of Robert I, Duke of Burgundy.[1][2] His two older brothers, Hugh I and Odo, inherited the duchy.[2] No contemporary record of his mother has survived. She was once thought to have been named Sibylla based on an undated obituary reporting the death of "Sibilla, mater ducus Burgundie" (Sibylla, mother of the Duke of Burgundy), under the reasoning that she was not called duchess herself and hence must have been the wife of Henry, the only father of a duke who never himself held the ducal title, yet this was probably a reference to her daughter-in-law, Sibylla, mother of the then-reigning Hugh II. Historian Jean Richard suggested that she might instead have been called Clémence.[3] Whatever her name, her son Henry was kinsman (congermanus) of his brother-in-law, Raymond of Burgundy, and this relationship may have come through either, or both, of their mothers, who are both of undocumented parentage. It has been suggested that Henry's mother may have been the daughter of Reginald I, which would make her the maternal aunt of Raymond who would then be Henry's first cousin.[4] This solution is problematic, as Henry's brother Odo I, Duke of Burgundy married Raymond's sister, Sibylla, and though marriages between close kin sometimes took place through dispensation, the prohibition against first-cousin marriages in church law makes it likely that the relationship between Odo and Sibylla, and hence that between Henry and Raymond, was more distant.[5] Based on the relationship between Henry and Raymond and the apparent introduction of the byname Borel into the family of the dukes of Burgundy through this marriage, genealogist Szabolcs de Vajay suggested Henry's mother was a daughter of Berenguer Ramon I, Count of Barcelona, and his wife Guisla de Lluçà.[6][7][lower-alpha 1]

One of his paternal aunts was Constance of Burgundy, the wife of Alfonso VI of León, and one of his great-uncles was Hugh, Abbot of Cluny, one of the most influential and venerated personalities of his time.[1] Count Henry's family was very powerful and governed many cities in France such as Chalon, Auxerre, Autun, Nevers, Dijon, Mâcon and Semur.[1]

Reconquista

After the defeat of the Christian troops in the Battle of Sagrajas in October 1086, in the early months of the following year, King Alfonso VI appealed for aid from Christians at the other side of the Pyrenees. Many French nobles and soldiers heeded the call, including Raymond of Burgundy, Henry's brother, Duke Odo, and Raymond of St. Gilles.[10] Not all of them arrived at the same time in the Iberian Peninsula and it is most likely that Raymond of Burgundy came in 1091.[11][lower-alpha 2] Although some authors claim that Count Henry came with the expedition which arrived in 1087, even though "documentary evidence here is much more slight",[13] his presence is confirmed only as of 1096 when he appears confirming the forais of Guimarães and Constantim de Panoias.

Three of these French nobles married daughters of King Alfonso VI: Raymond of Burgundy married infanta Urraca, later Queen Urraca of León; Raymond of St. Gilles married Elvira; and Henry of Burgundy married Teresa of León, an illegitimate daughter of the king and his mistress Jimena Muñoz.[14]

.png.webp)

Pact with his cousin Raymond of Burgundy

Between the years 1096 and 1105, count Raymond, seeing that his influence in the curia regis was diminishing, reached an agreement with his cousin Henry of Burgundy. The birth of King Alfonso's only son, Sancho Alfónsez, was also perceived as a threat by the two cousins. They agreed to share power, the royal treasury, and to support each other.[15] Under this agreement, which counted with the blessings of their relative, the Abbot of Cluny,[lower-alpha 3] Raymond "promised his cousin under oath to hand him over the Kingdom of Toledo and one third of the royal treasury upon the death of King Alfonso VI". If he could not deliver Toledo, he would give him Galicia. Henry, in turn, promised to help Raymond "obtain all the dominions of King Alfonso and two thirds of the royal treasury".[17][18]

Historians who date the pact closer to 1096 surmise that news of this agreement might have reached the king who, in order to counter the initiative of his two sons-in-law, appointed Henry governor of the region extending a flumine mineo usque in tagum (from the Minho river to the banks of the Tagus).[19] Until then, this region had been governed by count Raymond who saw his power limited to just Galicia, thereby nullifying the terms of the pact.[20][lower-alpha 4]

Other historians however have showed that the pact could not have been made before 1103,[21][22] several years after the two counts had been granted their respective title, implying that their alliance must have prevailed over their hypothetical rivalry.

After the death of Alfonso VI

.jpg.webp)

After Raymond's death, Queen Urraca (Teresa's half-sister) married Alfonso the Battler for political and strategic reasons. Henry took advantage of the family conflicts and political unrest to serve on both sides and aggrandize his domains at the cost of the squabbling royal couple.

Caught under siege in Astorga by the King of Aragon, then at war with Urraca, Henry held the city with the help of his sister-in-law. Henry died on 22 May 1112,[23] from wounds received during the siege.[24] His remains were transferred, following his previous orders, to Braga where he was buried in a chapel at Braga Cathedral, the building of which he had promoted.[25] After his death, his widow ruled alone.[26]

Legacy

Count Henry was the leader of a group of gentlemen, monks, and clerics of French origin who exerted great influence in the Iberian Peninsula, promoted many reforms and introduced several institutions from the other side of the Pyrenees, such as the customs of Cluny and the Roman Rite. They occupied relevant ecclesiastical and political positions which provoked a strong backlash during the last years of the reign of King Alfonso VI.[27]

Marriage and issue

He married Teresa of León around 1095.[28] From Teresa, Henry had the following issue:

- Urraca Henriques (c. 1095[29] – after 1169), the wife of Bermudo Pérez de Traba, tenente in Trastámara, Viseu, Seia, and Faro in A Coruña.[30]

- Sancha Henriques (c. 1097[29] – 1163), married the nobleman Sancho Nunes de Celanova. On 15 July 1129, the abbess of the Monastery of San Salvador de Ferreira de Pantón purchased from Mendo Núñez, his brother Sancho, and the wife of the latter, Sancha Henriques, some properties in Estriz.[31] One of their daughters, María, was the abbess at the Monastery of San Salvador de Sobrado de Trives. They were also the parents of count Velasco, Gil, Fernando and Teresa Sánchez.[31] After becoming a widow, she married Fernando Mendes de Bragança, with no issue from this second marriage.[32]

- Teresa Henriques (born c. 1098);[29]

- Afonso Henriques (1109[33] – 1185). He was named after his maternal grandfather, King Alfonso VI, perhaps "as a way of remembering that the blood of the Emperor of all Hispania also ran through his veins".[34] Afonso became Count of Portugal in 1112 and King of Portugal in 1139.[35]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Henry, Count of Portugal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- In an apparent editorial error, the Barcelona count in question is called "Raimond Berenger Ier" in Vajay's original presentation of the theory,[8] but the author's true intent is clear, having named the same Barcelona count correctly earlier in that paper,[9] while in a subsequent paper he cites his earlier work as concluding her parents were Berenger Ramon Ier and Guisla d'Ampurias.[7] This proposed ancestry for count Henry's mother was coupled to Vajay's hypothesis for the ancestry of Raymond of Burgundy's mother, Stephanie, that Vajay himself subsequently concluded was incorrect.[5]

- Reilly mentions that they were already married by 1087, the year of Raymond's arrival in Spain, although the marriage did not take place until 1095.[12]

- "The undated text, which has come down to us through Cluny, consists of a short note sent to Abbot Hugo by means of a messenger named Dalmacio Geret, which includes a copy of the oaths that the two cousins had made at the behest of the aforementioned abbot".[16]

- The pact between counts Raymond and Henry is reproduced in the work cited in the bibliography.[21]

References

- Mattoso 2014, p. 28.

- Martínez Díez 2003, p. 225.

- Richard 1958, pp. 38–9.

- Martínez Díez 2003, pp. 105 & 225.

- Vajay 2000, pp. 2–6.

- Vajay 1960, pp. 158–61.

- Vajay 1962, p. 167.

- Vajay 1960, pp. 160.

- Vajay 1960, pp. 257.

- Martínez Díez 2003, p. 105.

- Martínez Díez 2003, p. 223.

- Reilly 1982, p. 14, chapter I.

- Reilly 1982, p. 14, note 15, chapter I.

- Martínez Díez 2003, p. 162.

- Rodrigues Oliveira 2010, pp. 28–29.

- Martínez Díez 2003, p. 226.

- Martínez Díez 2003, p. 170.

- Reilly 1982, p. 27, note 55, chapter I.

- Reilly 1982, p. 29, note 59, chapter I.

- Martínez Díez 2003, pp. 170–171.

- David 1948, pp. 275–276.

- Bishko 1971, pp. 155–188.

- Mattoso 2014, p. 34.

- Reilly 1995, pp. 133−134.

- Caetano de Souza 1735, p. 37.

- Mattoso 2014, pp. 34–43.

- Mattoso 2014, p. 29.

- Rodrigues Oliveira 2010, p. 25.

- Rodrigues Oliveira 2010, p. 28.

- López Sangil 2002, p. 89.

- López Morán 2005, p. 89.

- Sotto Mayor Pizarro 2007, pp. 855 and 857-858.

- Rodrigues Oliveira 2010, p. 31.

- Rodrigues Oliveira 2010, p. 33.

- Reilly 1995, p. 203.

Bibliography

- Caetano de Souza, Antonio (1735). Historia Genealógica de la Real Casa Portuguesa (PDF) (in Portuguese). Vol. I, Books I and II. Lisbon: Lisbon Occidental, na oficina de Joseph Antonio da Sylva. ISBN 978-84-8109-908-9.

- David, Pierre (1948). "La pacte succesoral entre Raymond de Galice et Henri de Portugal". Bulletin Hispanique (in French). 50 (3): 275–290. doi:10.3406/hispa.1948.3146.

- Bishko, Charles J. (1971). "Count Henrique of Portugal, Cluny, and the antecedents of the Pacto Sucessório". Revista Portuguesa de Historia. 13 (13): 155–88. doi:10.14195/0870-4147_13_8.

- López Morán, Enriqueta (2005). "El monacato femenino gallego en la Alta Edad Media (Lugo y Orense) (Siglos XIII al XV)" (PDF). Nalgures (in Spanish). No. II. A Coruña: Asociación Cultura de Estudios Históricos de Galicia. pp. 49–142. ISSN 1885-6349. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-06.

- López Sangil, José Luis (2002). La nobleza altomedieval gallega, la familia Froílaz-Traba (in Spanish). La Coruña: Toxosoutos, S.L. ISBN 84-95622-68-8.

- Manrique, Ángel (1649). Anales cistercienses (in Latin). Vol. 2.

- Martínez Díez, Gonzalo (2003). Alfonso VI: Señor del Cid, conquistador de Toledo (in Spanish). Madrid: Temas de Hoy, S.A. ISBN 8484602516.

- Mattoso, José (2014). D. Afonso Henriques (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). Lisbon: Temas e Debates. ISBN 978-972-759-911-0.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1995). The Contest of Christian and Muslim Spain, 1031-1157. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell. ISBN 9780631169130.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1998). The Kingdom of León-Castilla Under King Alfonso VII, 1126-1157. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812234527.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1982). The Kingdom of León-Castilla Under Queen Urraca, 1109-1126. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780812234527.

- Richard, Jean (1958). "Sur les alliances familiales des ducs de Bourgogne aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles". Annales de Bourgogne (in French). 30: 34–46, 232.

- Rodrigues Oliveira, Ana (2010). Rainhas medievais de Portugal. Dezassete mulheres, duas dinastias, quatro séculos de História (in Portuguese). Lisbon: A esfera dos livros. ISBN 978-989-626-261-7.

- Sotto Mayor Pizarro, José Augusto (2007). "O regime senhorial na frontera do nordeste português. Alto Douro e Riba Côa (Séculos XI-XIII)". Hispania. Revista Española de Historia (in Portuguese). Vol. XVII, no. 227. Madrid: Instituto de Historia "Jerónimo Zurita; Centro de Estudios Históricos. pp. 849–880. ISSN 0018-2141.

- Vajay, Szabolcs de (1960). "Bourgogne, Lorraine et Espagne aux XIe siècle: Étiennette, dite de Vienne, comtesse de Bourgogne". Annales de Bourgogne (in French). 32: 233–66.

- Vajay, Szabolcs de (1962). "A propos de la 'Guerre de Bourgogne': Notes sur les successions de Bourgogne et de Mâcon aux Xe et XIe siècles". Annales de Bourgogne (in French). 34: 153–69.

- Vajay, Szabolcs de (2000), "Parlons encore d'Etiennette", in Keats-Rohan, Katharine S. B.; Settipani, Christian (eds.), Onomastique et Parente dans l'Occident medieval, Prosopographica et Genealogica no. 3 (in French), pp. 2–6