Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272.[1] The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry assumed the throne when he was only nine in the middle of the First Barons' War. Cardinal Guala Bicchieri declared the war against the rebel barons to be a religious crusade and Henry's forces, led by William Marshal, defeated the rebels at the battles of Lincoln and Sandwich in 1217. Henry promised to abide by the Great Charter of 1225, a later version of the 1215 Magna Carta, which limited royal power and protected the rights of the major barons. His early rule was dominated first by Hubert de Burgh and then Peter des Roches, who re-established royal authority after the war. In 1230, the King attempted to reconquer the provinces of France that had once belonged to his father, but the invasion was a debacle. A revolt led by William Marshal's son Richard broke out in 1232, ending in a peace settlement negotiated by the Church.

| Henry III | |

|---|---|

Henry III depicted in a manuscript from the 13th century | |

| King of England | |

| Reign | 28 October 1216 – 16 November 1272 |

| Coronation |

|

| Predecessor | John |

| Successor | Edward I |

| Regents | See list

|

| Born | 1 October 1207 Winchester Castle, Hampshire, England |

| Died | 16 November 1272 (aged 65) Westminster, London, England |

| Burial | Westminster Abbey, London, England |

| Consort | |

| Issue more... | |

| House | Plantagenet |

| Father | John, King of England |

| Mother | Isabella of Angoulême |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Following the revolt, Henry ruled England personally, rather than governing through senior ministers. He travelled less than previous monarchs, investing heavily in a handful of his favourite palaces and castles. He married Eleanor of Provence, with whom he had five children. Henry was known for his piety, holding lavish religious ceremonies and giving generously to charities; the King was particularly devoted to the figure of Edward the Confessor, whom he adopted as his patron saint. He extracted huge sums of money from the Jews in England, ultimately crippling their ability to do business, and as attitudes towards the Jews hardened, he introduced the Statute of Jewry, attempting to segregate the community. In a fresh attempt to reclaim his family's lands in France, he invaded Poitou in 1242, leading to the disastrous Battle of Taillebourg. After this, Henry relied on diplomacy, cultivating an alliance with Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor. Henry supported his brother Richard of Cornwall in his successful bid to become King of the Romans in 1256, but was unable to place his own son Edmund Crouchback on the throne of Sicily, despite investing large amounts of money. He planned to go on crusade to the Levant, but was prevented from doing so by rebellions in Gascony.

By 1258, Henry's rule was increasingly unpopular, the result of the failure of his expensive foreign policies and the notoriety of his Poitevin half-brothers, the Lusignans, as well as the role of his local officials in collecting taxes and debts. A coalition of his barons, initially probably backed by Eleanor, seized power in a coup d'état and expelled the Poitevins from England, reforming the royal government through a process called the Provisions of Oxford. Henry and the baronial government enacted a peace with France in 1259, under which Henry gave up his rights to his other lands in France in return for King Louis IX recognising him as the rightful ruler of Gascony. The baronial regime collapsed but Henry was unable to reform a stable government and instability across England continued.

In 1263, one of the more radical barons, Simon de Montfort, seized power, resulting in the Second Barons' War. Henry persuaded Louis to support his cause and mobilised an army. The Battle of Lewes was fought in 1264, when Henry was defeated and taken prisoner. Henry's eldest son, Edward, escaped from captivity to defeat de Montfort at the Battle of Evesham the following year and freed his father. Henry initially exacted a harsh revenge on the remaining rebels, but was persuaded by the Church to mollify his policies through the Dictum of Kenilworth. Reconstruction was slow, and Henry had to acquiesce to several measures, including further suppression of the Jews, to maintain baronial and popular support. Henry died in 1272, leaving Edward as his successor. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, which he had rebuilt in the second half of his reign, and was moved to his current tomb in 1290. Some miracles were declared after his death, but he was not canonised. Henry's reign of fifty-six years was the longest in medieval English history, and would not be surpassed by an English, or later British, monarch until that of George III in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Background and childhood

.svg.png.webp)

Henry was born in Winchester Castle on 1 October 1207.[2] He was the eldest son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême.[3] Little is known of Henry's early life.[4] He was initially looked after by a wet nurse called Ellen in the south of England, away from John's itinerant court, and probably had close ties to his mother.[5] Henry had four legitimate younger brothers and sisters – Richard, Joan, Isabella and Eleanor – and various older illegitimate siblings.[6] In 1212 his education was entrusted to Peter des Roches, the bishop of Winchester; under his direction, Henry was given military training by Philip D'Aubigny and taught to ride, probably by Ralph of St Samson.[7]

Little is known about Henry's appearance; he was probably around 1.68 metres (5 ft 6 in) tall, and accounts recorded after his death suggested that he had a strong build, with a drooping eyelid.[7][lower-alpha 1] Henry grew up to occasionally show flashes of a fierce temper, but mostly, as historian David Carpenter describes, he had an "amiable, easy-going, and sympathetic" personality.[8] He was unaffected and honest, and showed his emotions readily, easily being moved to tears by religious sermons.[8]

At the start of the 13th century, the Kingdom of England formed part of the Angevin Empire spreading across Western Europe. Henry was named after his grandfather, Henry II, who had built up this vast network of lands stretching from Scotland and Wales, through England, across the English Channel to the territories of Normandy, Brittany, Maine and Anjou in north-west France, and on to Poitou and Gascony in the south-west.[9] For many years the French Crown was relatively weak, enabling first Henry II, and then his sons Richard I and John, to dominate France.[10]

In 1204, John lost Normandy, Brittany, Maine and Anjou to Philip II of France, leaving English power on the continent limited to Gascony and Poitou.[11] John raised taxes to pay for military campaigns to regain his lands, but unrest grew among many of the English barons; John sought new allies by declaring England a papal fiefdom, owing allegiance to the Pope.[12][lower-alpha 2] In 1215, John and the rebel barons negotiated a potential peace treaty, the Magna Carta. The treaty would have limited potential abuses of royal power, demobilised the rebel armies and set up a power-sharing arrangement, but in practice neither side complied with its conditions.[14] John and the loyalist barons firmly repudiated the Magna Carta and the First Barons' War erupted, with the rebel barons aided by Philip's son, the future Louis VIII, who claimed the English throne for himself.[11] The war soon settled into a stalemate, with neither side able to claim victory. The king became ill, and died on the night of 18 October, leaving the nine-year-old Henry as his heir.[15]

Minority (1216–26)

Coronation

Henry was staying safely at Corfe Castle in Dorset with his mother when King John died.[16] On his deathbed, John appointed a council of thirteen executors to help Henry reclaim the kingdom, and requested that his son be placed into the guardianship of William Marshal, one of the most famous knights in England.[17] The loyalist leaders decided to crown Henry immediately to reinforce his claim to the throne.[18][lower-alpha 3] William knighted the boy, and Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, the papal legate to England, then oversaw his coronation at Gloucester Cathedral on 28 October 1216.[19]

In the absence of Archbishops Stephen Langton of Canterbury and Walter de Gray of York, he was anointed by Sylvester, Bishop of Worcester, and Simon, Bishop of Exeter, and crowned by Peter des Roches.[19] The royal crown had been either lost or sold during the civil war or possibly lost in The Wash, so instead the ceremony used a simple gold corolla belonging to Queen Isabella.[20] Henry later underwent a second coronation at Westminster Abbey on 17 May 1220.[21]

The young king inherited a difficult situation, with over half of England occupied by the rebels and most of his father's continental possessions still in French hands.[22] He had substantial support from Cardinal Guala, who intended to win the civil war for Henry and punish the rebels.[23] Guala set about strengthening the ties between England and the Papacy, starting with the coronation itself, where Henry gave homage to the Papacy, recognising Pope Honorius III as his feudal lord.[24] Honorius declared that Henry was his vassal and ward, and that the legate had complete authority to protect Henry and his kingdom.[18] As an additional measure, Henry took the cross, declaring himself a crusader and so entitled to special protection from Rome.[18]

Two senior nobles stood out as candidates to head Henry's regency government.[25] The first was William, who, although elderly, was renowned for his personal loyalty and could help support the war with his own men and material.[26] The second was Ranulf de Blondeville, 6th Earl of Chester, one of the most powerful loyalist barons. William diplomatically waited until both Guala and Ranulf had requested him to take up the post before assuming power.[27][lower-alpha 4] William then appointed des Roches to be Henry's guardian, freeing himself up to lead the military effort.[29]

End of the Barons' War

The war was not going well for the loyalists and the new regency government considered retreating to Ireland.[31] Prince Louis and the rebel barons were also finding it difficult to make further progress. Despite Louis controlling Westminster Abbey, he could not be crowned king because the English Church and the Papacy backed Henry.[32] John's death had defused some of the rebel concerns, and the royal castles were still holding out in the occupied parts of the country.[33] In a bid to take advantage of this, Henry encouraged the rebel barons to come back to his cause in exchange for the return of their lands, and reissued a version of the Magna Carta, albeit having first removed some of the clauses, including those unfavourable to the Papacy.[34] The move was not successful and opposition to Henry's new government hardened.[35]

In February, Louis set sail for France to gather reinforcements.[36] In his absence, arguments broke out between Louis's French and English followers, and Cardinal Guala declared that Henry's war against the rebels was a religious crusade.[37][lower-alpha 5] This resulted in a series of defections from the rebel movement, and the tide of the conflict swung in Henry's favour.[39] Louis returned at the end of April and reinvigorated his campaign, splitting his forces into two groups, sending one north to besiege Lincoln Castle and keeping one in the south to capture Dover Castle.[40] When he learnt that Louis had divided his army, William Marshal gambled on defeating the rebels in a single battle.[41] William marched north and attacked Lincoln on 20 May; entering through a side gate, he took the city in a sequence of fierce street battles and sacked the buildings.[42] Large numbers of senior rebels were captured, and historian David Carpenter considers the battle to be "one of the most decisive in English history".[43][lower-alpha 6]

In the aftermath of Lincoln, the loyalist campaign stalled and only recommenced in late June when the victors had arranged the ransoming of their prisoners.[45] Meanwhile, support for Louis's campaign was diminishing in France and he concluded that the war in England was lost.[46][lower-alpha 7] Louis negotiated terms with Cardinal Guala, under which he would renounce his claim to the English throne; in return, his followers would be given back their lands, any sentences of excommunication would be lifted and Henry's government would promise to enforce the Magna Carta.[47] The proposed agreement soon began to unravel amid claims from some loyalists that it was too generous towards the rebels, particularly the clergy who had joined the rebellion.[48] In the absence of a settlement, Louis remained in London with his remaining forces.[48]

On 24 August 1217, a French fleet arrived off the coast of Sandwich, bringing Louis soldiers, siege engines and fresh supplies.[49] Hubert de Burgh, Henry's justiciar, set sail to intercept it, resulting in the Battle of Sandwich.[50] De Burgh's fleet scattered the French and captured their flagship, commanded by Eustace the Monk, who was promptly executed.[50] When the news reached Louis, he entered into fresh peace negotiations.[50]

Henry, Isabella, Louis, Guala and William came to agreement on the final Treaty of Lambeth, also known as the Treaty of Kingston, on 12 and 13 September.[50] The treaty was similar to the first peace offer, but excluded the rebel clergy, whose lands and appointments remained forfeit.[51] Louis accepted a gift of £6,666 to speed his departure from England, and promised to try to persuade King Philip to return Henry's lands in France.[52][lower-alpha 8] Louis left England as agreed and joined the Albigensian Crusade in the south of France.[46]

Restoring royal authority

With the end of the civil war, Henry's government faced the task of rebuilding royal authority across large parts of the country.[54] By the end of 1217, many former rebels were routinely ignoring instructions from the centre, and even Henry's loyalist supporters jealously maintained their independent control over royal castles.[55] Illegally constructed fortifications, called adulterine castles, had sprung up across much of the country. The network of county sheriffs had collapsed, and with it the ability to raise taxes and collect royal revenues.[56] The powerful Welsh Prince Llywelyn posed a major threat in Wales and along the Welsh Marches.[57]

Despite his success in winning the war, William had far less success in restoring royal power following the peace.[58] In part, this was because he was unable to offer significant patronage, despite the expectations from the loyalist barons that they would be rewarded.[59][lower-alpha 9] William attempted to enforce the traditional rights of the Crown to approve marriages and wardships, but with little success.[61] Nonetheless, he was able to reconstitute the royal bench of judges and reopen the royal exchequer.[62] The government issued the Charter of the Forest, which attempted to reform the royal governance of the forests.[63] The regency and Llywelyn came to agreement on the Treaty of Worcester in 1218, but its generous terms – Llywelyn became effectively Henry's justiciar across Wales – underlined the weakness of the English Crown.[64]

Henry's mother was unable to establish a role for herself in the regency government and she returned to France in 1217, marrying Hugh X de Lusignan, a powerful Poitevin noble.[65][lower-alpha 10] William Marshal fell ill and died in April 1219. The replacement government was formed around a grouping of three senior ministers: Pandulf Verraccio, the replacement Papal legate; Peter des Roches; and Hubert de Burgh, a former justiciar.[67] The three were appointed by a great council of the nobility at Oxford, and their government came to depend on these councils for authority.[68] Hubert and des Roches were political rivals, with Hubert supported by a network of English barons, and des Roches backed by nobles from the royal territories in Poitou and Touraine.[69][lower-alpha 11] Hubert moved decisively against des Roches in 1221, accusing him of treason and removing him as the King's guardian; the Bishop left England for the crusades.[71] Pandulf was recalled by Rome the same year, leaving Hubert as the dominant force in Henry's government.[72]

Initially the new government had little success, but in 1220, the fortunes of Henry's government began to improve.[73] The Pope allowed Henry to be crowned for a second time, using a new set of royal regalia.[74] The fresh coronation was intended to affirm the authority of the King; Henry promised to restore the powers of the Crown, and the barons swore that they would give back the royal castles and pay their debts to the Crown, on the threat of excommunication.[75] Hubert, accompanied by Henry, moved into Wales to suppress Llywelyn in 1223, and in England his forces steadily reclaimed Henry's castles.[76] The effort against the remaining recalcitrant barons came to a head in 1224 with the siege of Bedford Castle, which Henry and Hubert besieged for eight weeks; when it finally fell, almost all of the garrison were executed and the castle was methodically slighted.[77]

Meanwhile, Louis VIII of France allied himself with Hugh de Lusignan and invaded first Poitou and then Gascony.[78] Henry's army in Poitou was under-resourced and lacked support from the Poitevin barons, many of whom had felt abandoned during the years of Henry's minority; as a result, the province quickly fell.[79] It became clear that Gascony would also fall unless reinforcements were sent from England.[80] In early 1225 a great council approved a tax of £40,000 to dispatch an army, which quickly retook Gascony.[81][lower-alpha 8] In exchange for agreeing to support Henry, the barons demanded that he reissue the Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest.[82] This time the King declared that the charters were issued of his own "spontaneous and free will" and confirmed them with the royal seal, giving the new Great Charter and the Charter of the Forest of 1225 much more authority than any previous versions.[83] The barons anticipated that the King would act in accordance with these definitive charters, subject to the law and moderated by the advice of the nobility.[84]

Early rule (1227–34)

Invasion of France

Henry assumed formal control of his government in January 1227, although some contemporaries argued that he was legally still a minor until his 21st birthday the following year.[85] The King richly rewarded Hubert de Burgh for his service during his minority years, making him the Earl of Kent and giving him extensive lands across England and Wales.[86] Despite coming of age, Henry remained heavily influenced by his advisers for the first few years of his rule and retained Hubert as his justiciar to run the government, granting him the position for life.[87]

The fate of Henry's family lands in France still remained uncertain. Reclaiming these lands was extremely important to Henry, who used terms such as "reclaiming his inheritance", "restoring his rights" and "defending his legal claims" to the territories in diplomatic correspondence.[88] The French kings had an increasing financial, and thus military, advantage over Henry.[89] Even under John, the French Crown had enjoyed a considerable, although not overwhelming, advantage in resources, but since then, the balance had shifted further, with the ordinary annual income of the French kings almost doubling between 1204 and 1221.[90]

Louis VIII died in 1226, leaving his 12-year-old son, Louis IX, to inherit the throne, supported by a regency government.[91][lower-alpha 12] The young French king was in a much weaker position than his father, and faced opposition from many of the French nobility who still maintained their ties to England, leading to a sequence of revolts across the country.[92] Against this background, in late 1228 a group of potential Norman and Angevin rebels called upon Henry to invade and reclaim his inheritance, and Peter I, Duke of Brittany, openly revolted against Louis and gave his homage to Henry.[93]

Henry's preparations for an invasion progressed slowly, and when he finally arrived in Brittany with an army in May 1230, the campaign did not go well.[94] Possibly on the advice of Hubert, the King decided to avoid battle with the French by not invading Normandy and instead marching south into Poitou, where he campaigned ineffectually over the summer, before finally progressing safely onto Gascony.[93] He made a truce with Louis until 1234 and returned to England having achieved nothing; historian Huw Ridgeway describes the expedition as a "costly fiasco".[7]

Richard Marshal's revolt

Henry's chief minister, Hubert, fell from power in 1232. His old rival, Peter des Roches, returned to England from the crusades in August 1231 and allied himself with Hubert's growing number of political opponents.[95] He put the case to Henry that the Justiciar had squandered royal money and lands, and was responsible for a series of riots against foreign clerics.[96] Hubert took sanctuary in Merton Priory, but Henry had him arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London.[96] Des Roches took over the King's government, backed by the Poitevin baronial faction in England, who saw this as a chance to take back the lands which they had lost to Hubert's followers in the previous decades.[97]

Des Roches used his new authority to begin stripping his opponents of their estates, circumventing the courts and legal process.[97] Complaints from powerful barons such as William Marshal's son Richard Marshal, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, grew, and they argued that Henry was failing to protect their legal rights as described in the 1225 charters.[98] A fresh civil war broke out between des Roches and Richard's followers.[99] Des Roches sent armies into Richard's lands in Ireland and South Wales.[99] In response, Richard allied himself with Prince Llywelyn, and his own supporters rose up in rebellion in England.[99] Henry was unable to gain a clear military advantage and became concerned that Louis of France might seize the opportunity to invade Brittany – where the truce was about to expire – while he was distracted at home.[99]

Edmund of Abingdon, the Archbishop of Canterbury, intervened in 1234 and held several great councils, advising Henry to accept the dismissal of des Roches.[99] Henry agreed to make peace, but, before the negotiations were completed, Richard died of wounds suffered in battle, leaving his younger brother Gilbert to inherit his lands.[100] The final settlement was confirmed in May, and Henry was widely praised for his humility in submitting to the slightly embarrassing peace.[100] Meanwhile, the truce with France in Brittany finally expired, and Henry's ally Duke Peter came under fresh military pressure.[101] Henry could only send a small force of soldiers to assist, and Brittany fell to Louis in November.[101] For the next 24 years, Henry ruled the kingdom personally, rather than through senior ministers.[102]

Henry as king

Kingship, government and law

Royal government in England had traditionally centred on several great offices of state, filled by powerful, independent members of the baronage.[103] Henry abandoned this policy, leaving the post of justiciar vacant and turning the position of chancellor into a more junior role.[104] A small royal council was formed but its role was ill-defined; appointments, patronage, and policy were decided personally by Henry and his immediate advisers, rather than through the larger councils that had marked his early years.[105] The changes made it much harder for those outside Henry's inner circle to influence policy or to pursue legitimate grievances, particularly against the King's friends.[103]

Henry believed that kings should rule England in a dignified manner, surrounded by ceremony and ecclesiastical ritual.[106] He thought that his predecessors had allowed the status of the Crown to decline, and sought to correct this during his reign.[106] The events of the civil war in Henry's youth deeply affected him, and he adopted Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor as his patron saint, hoping to emulate the way in which Edward had brought peace to England and reunited his people in order and harmony.[107] Henry tried to use his royal authority leniently, hoping to appease the more hostile barons and maintain peace in England.[7]

As a result, despite a symbolic emphasis on royal power, Henry's rule was relatively circumscribed and constitutional.[108] He generally acted within the terms of the charters, which prevented the Crown from taking extrajudicial action against the barons, including the fines and expropriations that had been common under John.[108] The charters did not address the sensitive issues of the appointment of royal advisers and the distribution of patronage, and they lacked any means of enforcement if the King chose to ignore them.[109] Henry's rule became lax and careless, resulting in a reduction in royal authority in the provinces and, ultimately, the collapse of his authority at court.[110] The inconsistency with which he applied the charters over the course of his rule alienated many barons, even those within his own faction.[7]

.jpg.webp)

The term "parliament" first appeared in the 1230s and 1240s to describe large gatherings of the royal court, and parliamentary gatherings were held periodically throughout Henry's reign.[111] They were used to agree upon the raising of taxes which, in the 13th century, were single, one-off levies, typically on movable property, intended to support the King's normal revenues for particular projects.[112][lower-alpha 13] During Henry's reign, the counties began to send regular delegations to these parliaments, and came to represent a broader cross-section of the community than simply the major barons.[115]

Despite the various charters, the provision of royal justice was inconsistent and driven by the needs of immediate politics: sometimes action would be taken to address a legitimate baronial complaint, on other occasions, the problem would simply be ignored.[116] The royal eyres, courts which toured the country to provide justice at the local level, typically for those lesser barons and the gentry claiming grievances against the major lords, had little power, allowing the major barons to dominate the local justice system.[117]

The power of royal sheriffs also declined during Henry's reign. They were now often lesser men appointed by the exchequer, rather than coming from important local families, and they focused on generating revenue for the King.[118] Their robust attempts to enforce fines and collect debts generated much unpopularity among the lower classes.[119] Unlike his father, Henry did not exploit the large debts that the barons frequently owed to the Crown, and was slow to collect any sums of money due to him.[120]

Court

The royal court was formed round Henry's trusted friends, such as Richard de Clare, 6th Earl of Gloucester; the brothers Hugh Bigod and Roger Bigod, 4th Earl of Norfolk; Humphrey de Bohun, 2nd Earl of Hereford; and Henry's brother, Richard.[121] Henry wanted to use his court to unite his English and continental subjects, and it included the originally French knight Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, who had married Henry's sister Eleanor, in addition to the later influxes of Henry's Savoyard and Lusignan relatives.[122] The court followed European styles and traditions, and was heavily influenced by Henry's Angevin family traditions: French was the spoken language, it had close links to the royal courts of France, Castile, the Holy Roman Empire and Sicily, and Henry sponsored the same writers as the other European rulers.[123]

Henry travelled less than previous kings, seeking a tranquil, more sedate life and staying at each of his palaces for prolonged periods before moving on.[124] Possibly as a result, he focused more attention on his palaces and houses; Henry was, according to architectural historian John Goodall, "the most obsessive patron of art and architecture ever to have occupied the throne of England".[125] Henry extended the royal complex at Westminster in London, one of his favourite homes, rebuilding the palace and the abbey at a cost of almost £55,000.[126][lower-alpha 8] He spent more time in Westminster than any of his predecessors, shaping the formation of England's capital city.[127]

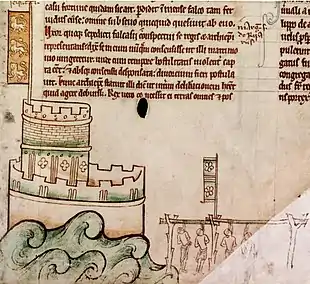

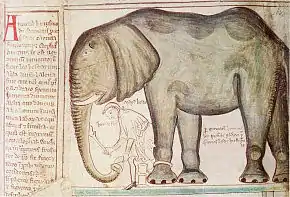

He spent £58,000 on his royal castles, carrying out major works at the Tower of London, Lincoln and Dover.[128][lower-alpha 8] Both the military defences and the internal accommodation of these castles were significantly improved.[129] A huge overhaul of Windsor Castle produced a lavish palace complex, whose style and detail inspired many subsequent designs in England and Wales.[130] The Tower of London was extended to form a concentric fortress with extensive living quarters, although Henry primarily used the castle as a secure retreat in the event of war or civil strife.[131] He also kept a menagerie at the Tower, a tradition begun by his father, and his exotic specimens included an elephant, a leopard and a camel.[132][lower-alpha 14]

Henry reformed the system of silver coins in England in 1247, replacing the older Short Cross silver pennies with a new Long Cross design.[133] Due to the initial costs of the transition, he required the financial help of his brother Richard to undertake this reform, but the recoinage occurred quickly and efficiently.[134] Between 1243 and 1258, the King assembled two great hoards, or stockpiles, of gold.[135] In 1257, Henry needed to spend the second of these hoards urgently and, rather than selling the gold quickly and depressing its value, he decided to introduce gold pennies into England, following the popular trend in Italy.[136] The gold pennies resembled the gold coins issued by Edward the Confessor, but the overvalued currency attracted complaints from the City of London and was ultimately abandoned.[137][lower-alpha 15]

Religion

Henry was known for his public demonstrations of piety, and appears to have been genuinely devout.[139] He promoted rich, luxurious Church services, and, unusually for the period, attended mass at least once a day.[140][lower-alpha 16] He gave generously to religious causes, paid for the feeding of 500 paupers each day and helped orphans.[7] He fasted before commemorating Edward the Confessor's feasts, and may have washed the feet of lepers.[139] Henry regularly went on pilgrimages, particularly to the abbeys of Bromholm, St Albans and Walsingham Priory, although he appears to have sometimes used pilgrimages as an excuse to avoid dealing with pressing political problems.[142]

Henry shared many of his religious views with Louis of France, and the two men appear to have been slightly competitive in their piety.[143] Towards the end of his reign, Henry may have taken up the practice of curing sufferers of scrofula, often called "the King's evil", by touching them, possibly emulating Louis, who also took up the practice.[144][lower-alpha 17] Louis had a famous collection of Passion Relics which he kept in the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, and he paraded the Holy Cross through Paris in 1241; Henry took possession of the Relic of the Holy Blood in 1247, marching it through Westminster to be installed in Westminster Abbey, which he promoted as an alternative to the Sainte-Chapelle.[146][lower-alpha 18]

Henry was particularly supportive of the mendicant orders; his confessors were drawn from the Dominican friars, and he built mendicant houses in Canterbury, Norwich, Oxford, Reading and York, helping to find valuable space for new buildings in what were already crowded towns and cities.[148] He supported the military crusading orders, and became a patron of the Teutonic Order in 1235.[149] The emerging universities of Oxford and Cambridge also received royal attention: Henry reinforced and regulated their powers, and encouraged scholars to migrate from Paris to teach at them.[150] A rival institution at Northampton was declared by the King to be a mere school and not a true university.[151]

The support given to Henry by the Papacy during his early years had a lasting influence on his attitude towards Rome, and he defended the mother church diligently throughout his reign.[152][lower-alpha 19] Rome in the 13th century was at once both the centre of the Europe-wide Church, and a political power in central Italy, threatened militarily by the Holy Roman Empire. During Henry's reign, the Papacy developed a strong, central bureaucracy, supported by benefices granted to absent churchmen working in Rome.[153] Tensions grew between this practice and the needs of local parishioners, exemplified by the dispute between Robert Grosseteste, the bishop of Lincoln, and the Papacy in 1250.[154]

Although the Scottish Church became more independent of England during the period, the Papal Legates helped Henry continue to apply influence over its activities at a distance.[155] Pope Innocent IV's attempts to raise funds began to face opposition from within the English Church during Henry's reign.[156] In 1240, the Papal emissary's collection of taxes to pay for the Papacy's war with Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II resulted in protests, ultimately overcome with the help of Henry and the Pope, and in the 1250s Henry's crusading tithes faced similar resistance.[157][lower-alpha 20]

Jewish policies

The Jews in England were considered the property of the Crown, and they had traditionally been used as a source of cheap loans and easy taxation, in exchange for royal protection against antisemitism.[114] The Jews had suffered considerable oppression during the First Barons' War, but during Henry's early years the community had flourished and became one of the most prosperous in Europe.[159] This was primarily the result of the stance taken by the regency government, which took a range of measures to protect the Jews and encourage lending.[160] This was driven by financial self-interest, as they stood to profit considerably from a strong Jewish community in England.[160] Their policy ran counter to the instructions being sent from the Pope, who had laid out strong anti-Jewish measures at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215; William Marshal continued with his policy despite complaints from the Church.[160]

In 1239 Henry introduced different policies, possibly trying to imitate those of Louis of France: Jewish leaders across England were imprisoned and forced to pay fines equivalent to a third of their goods, and any outstanding loans were to be released.[161] Further huge demands for cash followed – £40,000 was demanded in 1244, for example, of which around two-thirds was collected within five years – destroying the ability of the Jewish community to lend money commercially.[162] The financial pressure Henry placed on the Jews caused them to force repayment of loans, fuelling anti-Jewish resentment.[163] A particular grievance among smaller landowners such as knights was the sale of Jewish bonds, which were bought and used by richer barons and members of Henry's royal circle as a means to acquire lands of lesser landholders, through payment defaults.[164][lower-alpha 21]

Henry had built the Domus Conversorum in London in 1232 to help convert Jews to Christianity, and efforts intensified after 1239. As many as 10 per cent of the Jews in England had been converted by the late 1250s[165] in large part due to their deteriorating economic conditions.[166] Many anti-Jewish stories involving tales of child sacrifice circulated in the 1230s–50s,[167] including the account of "Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln" in 1255.[168] The event is considered particularly significant, as the first such accusation endorsed by the Crown.[169][lower-alpha 22] Henry intervened to order the execution of Copin, who had confessed to the murder in return for his life, and removed 91 Jews to the Tower of London. 18 were executed, and their property expropriated by the Crown. At the time, the Jews were mortgaged to Richard of Cornwall, who intervened to release the Jews that were not executed, probably also with the backing of Dominican or Franciscan friars.[170][lower-alpha 23]

Henry passed the Statute of Jewry in 1253, which attempted to stop the construction of synagogues and enforce the wearing of Jewish badges, in line with existing Church pronouncements; it remains unclear to what extent the King actually implemented the statute.[171] By 1258, Henry's Jewish policies were regarded as confused and were increasingly unpopular amongst the barons.[172] Taken together, Henry's policies up to 1258 of excessive Jewish taxation, anti-Jewish legislation and propaganda caused a very important and negative change.[169]

Personal rule (1234–58)

Marriage

Henry investigated a range of potential marriage partners in his youth, but they all proved unsuitable for reasons of European and domestic politics.[173][lower-alpha 24] In 1236 he finally married Eleanor of Provence, the daughter of Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Provence, and Beatrice of Savoy.[175] Eleanor was well-mannered, cultured and articulate, but the primary reason for the marriage was political, as Henry stood to create a valuable set of alliances with the rulers of the south and south-east of France.[176] Over the coming years, Eleanor emerged as a hard-headed, firm politician. Historians Margaret Howell and David Carpenter describe her as being "more combative" and "far tougher and more determined" than her husband.[177]

The marriage contract was confirmed in 1235 and Eleanor travelled to England to meet Henry for the first time.[178] The pair were married at Canterbury Cathedral in January 1236, and Eleanor was crowned queen at Westminster shortly afterwards in a lavish ceremony planned by Henry.[179] There was a substantial age gap between the couple – Henry was 28, Eleanor only 12 – but historian Margaret Howell observes that the King "was generous and warm-hearted and prepared to lavish care and affection on his wife".[180] Henry gave Eleanor extensive gifts and paid personal attention to establishing and equipping her household.[181] He also brought her fully into his religious life, including involving her in his devotion to Edward the Confessor.[182]

Despite initial concerns that the Queen might be barren, Henry and Eleanor had five children together.[183][lower-alpha 25] In 1239 Eleanor gave birth to their first child, Edward, named after the Confessor.[7] Henry was overjoyed and held huge celebrations, giving lavishly to the Church and to the poor to encourage God to protect his young son.[189] Their first daughter, Margaret, named after Eleanor's sister, followed in 1240, her birth also accompanied by celebrations and donations to the poor.[190] The third child, Beatrice, was named after Eleanor's mother, and born in 1242 during a campaign in Poitou.[191]

Their fourth child, Edmund, arrived in 1245 and was named after the 9th-century saint. Concerned about Eleanor's health, Henry donated large amounts of money to the Church throughout the pregnancy.[192] A third daughter, Katherine, was born in 1253 but soon fell ill, possibly the result of a degenerative disorder such as Rett syndrome, and was unable to speak.[193] She died in 1257 and Henry was distraught.[193][lower-alpha 26] His children spent most of their childhood at Windsor Castle and he appears to have been extremely attached to them, rarely spending extended periods of time apart from his family.[195]

After Eleanor's marriage, many of her Savoyard relatives joined her in England.[196] At least 170 Savoyards arrived in England after 1236, coming from Savoy, Burgundy and Flanders, including Eleanor's uncles, the later Archbishop Boniface of Canterbury and William of Savoy, Henry's chief adviser for a short period.[197] Henry arranged marriages for many of them into the English nobility, a practice that initially caused friction with the English barons, who resisted landed estates passing into the hands of foreigners.[198] The Savoyards were careful not to exacerbate the situation and became increasingly integrated into English baronial society, forming an important power base for Eleanor in England.[199]

Poitou and the Lusignans

In 1241, the barons in Poitou, including Henry's step-father Hugh de Lusignan, rebelled against the rule of Louis of France.[200] The rebels had counted on aid from Henry, but he lacked domestic support and was slow to mobilise an army, not arriving in France until the next summer.[201] His campaign was hesitant and was further undermined by Hugh switching sides and returning to support Louis.[201] On 20 May Henry's army was surrounded by the French at Taillebourg. Henry's brother Richard persuaded the French to delay their attack and the King took the opportunity to escape to Bordeaux.[201]

Simon de Montfort, who fought a successful rearguard action during the withdrawal, was furious with the King's incompetence and told Henry that he should be locked up like the 10th-century Carolingian king Charles the Simple.[202] The Poitou rebellion collapsed and Henry entered into a fresh five-year truce. His campaign had been a disastrous failure and had cost over £80,000.[203][lower-alpha 8]

In the aftermath of the revolt, French power extended throughout Poitou, threatening the interests of the Lusignan family.[200] In 1247 Henry encouraged his relatives to travel to England, where they were rewarded with large estates, largely at the expense of the English barons.[204][lower-alpha 27] More Poitevins followed, until around 100 had settled in England, around two-thirds of them being granted substantial incomes worth £66 or more by Henry.[206][lower-alpha 8] Henry encouraged some to help him on the continent; others acted as mercenaries and diplomatic agents, or fought on Henry's behalf in European campaigns.[207] Many were given estates along the contested Welsh Marches, or in Ireland, where they protected the frontiers.[208] For Henry, the community was an important symbol of his hopes to one day reconquer Poitou and the rest of his French lands, and many of the Lusignans became close friends with his son Edward.[209]

The presence of Henry's extended family in England proved controversial.[206] Concerns were raised by contemporary chroniclers – especially in works of Roger de Wendover and Matthew Paris – about the number of foreigners in England and historian Martin Aurell notes the xenophobic overtones of their commentary.[210] The term "Poitevins" became loosely applied to this grouping, although many came from Anjou and other parts of France, and by the 1250s there was a fierce rivalry between the relatively well established Savoyards and the newly arrived Poitevins.[211] The Lusignans began to break the law with impunity, pursuing personal grievances against other barons and the Savoyards, and Henry took little or no action to restrain them.[212] By 1258, the general dislike of the Poitevins had turned into hatred, with Simon de Montfort one of their strongest critics.[213]

Scotland, Wales and Ireland

Henry's position in Wales was strengthened during the first two decades of his personal rule.[214] Following the death of Llywelyn the Great in 1240, Henry's power in Wales expanded.[215] Three military campaigns were carried out in the 1240s, new castles were constructed and the royal lands in the County of Chester were expanded, increasing Henry's dominance over the Welsh princes.[216] Dafydd, Llywelyn's son, resisted the incursions, but died in 1246, and Henry confirmed the Treaty of Woodstock the following year with Owain and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Llywelyn the Great's grandsons, under which they ceded land to the King but retained the heart of their princedom in Gwynedd.[217]

In South Wales, Henry gradually extended his authority across the region, but the campaigns were not pursued with vigour and the King did little to stop the Marcher territories along the border becoming increasingly independent of the Crown.[218] In 1256, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd rebelled against Henry and widespread violence spread across Wales. Henry promised a swift military response but did not carry through on his threats.[219]

Ireland was important to Henry, both as a source of royal revenue – an average of £1,150 was sent from Ireland to the Crown each year during the middle of his reign – and as a source of estates that could be granted to his supporters.[220][lower-alpha 8] The major landowners looked eastwards towards Henry's court for political leadership, and many also possessed estates in Wales and England.[221] The 1240s saw major upheavals in land ownership due to deaths among the barons, enabling Henry to redistribute Irish lands to his supporters.[222]

In the 1250s, the King gave out numerous grants of land along the frontier in Ireland to his supporters, creating a buffer zone against the native Irish. The local Irish kings began to suffer increased harassment as English power increased across the region.[223] These lands were in many cases unprofitable for the barons to hold and English power reached its zenith under Henry for the medieval period.[224] In 1254, Henry granted Ireland to his son, Edward, on condition that it would never be separated from the Crown.[214]

Henry maintained peace with Scotland during his reign, where he was the feudal lord of Alexander II.[225] Henry assumed that he had the right to interfere in Scottish affairs and brought up the issue of his authority with the Scottish kings at key moments, but he lacked the inclination or the resources to do much more.[226] Alexander had occupied parts of northern England during the First Barons' War but had been excommunicated and forced to retreat.[227] Alexander married Henry's sister Joan in 1221, and after he and Henry signed the Treaty of York in 1237, Henry had a secure northern frontier.[228] Henry knighted Alexander III before the young king married Henry's daughter Margaret in 1251 and, despite Alexander's refusal to give homage to Henry for Scotland, the two enjoyed a good relationship.[229] Henry had Alexander and Margaret rescued from Edinburgh Castle when they were imprisoned there by a rebellious Scottish baron in 1255 and took additional measures to manage Alexander's government during the rest of his minority years.[230]

European strategy

Henry had no further opportunities to reconquer his possessions in France after the collapse of his military campaign at the Battle of Taillebourg.[7] Henry's resources were quite inadequate in comparison to those of the French Crown, and by the end of the 1240s it was clear that King Louis had become the preeminent power across France.[231] Henry instead adopted what historian Michael Clanchy has described as a "European strategy", attempting to regain his lands in France through diplomacy rather than force, building alliances with other states prepared to put military pressure on the French King.[232] In particular, Henry cultivated Frederick II, hoping he would turn against Louis or allow his nobility to join Henry's campaigns.[233] In the process, Henry's attention became increasingly focused on European politics and events rather than domestic affairs.[234]

Crusading was a popular cause in the 13th century, and in 1248 Louis joined the ill-fated Seventh Crusade, having first made a fresh truce with England and received assurances from the Pope that he would protect his lands against any attack by Henry.[235] Henry might have joined this crusade himself, but the rivalry between the two kings made this impossible and, after Louis's defeat at the Battle of Al Mansurah in 1250, Henry instead announced that he would be undertaking his own crusade to the Levant.[236][lower-alpha 28] He began to make arrangements for passage with friendly rulers around the Levant, imposing efficiency savings on the royal household and arranging for ships and transport: he appeared almost over-eager to take part.[238] Henry's plans reflected his strong religious beliefs, but they also stood to give him additional international credibility when arguing for the return of his possessions in France.[239]

Henry's crusade never departed, as he was forced to deal with problems in Gascony, where the harsh policies of his lieutenant, Simon de Montfort, had provoked a violent uprising in 1252, which was supported by King Alfonso X of neighbouring Castile.[240] The English court was split over the problem: Simon and Eleanor argued that the Gascons were to blame for the crisis, while Henry, backed by the Lusignans, blamed Simon's misjudgment.[7] Henry and Eleanor quarrelled over the issue and were not reconciled until the following year.[7] Forced to intervene personally, Henry carried out an effective, if expensive, campaign with the help of the Lusignans and stabilised the province.[241] Alfonso signed a treaty of alliance in 1254, and Gascony was given to Henry's son Edward, who married Alfonso's half-sister Eleanor, delivering a long-lasting peace with Castile.[242]

On the way back from Gascony, Henry met with Louis for the first time in an arrangement brokered by their wives, and the two kings became close friends.[243] The Gascon campaign cost more than £200,000 and used up all the money intended for Henry's crusade, leaving him heavily in debt and reliant on loans from his brother Richard and the Lusignans.[244]

The Sicilian business

Henry did not give up on his hopes for a crusade, but became increasingly absorbed in a bid to acquire the wealthy Kingdom of Sicily for his son Edmund.[245] Sicily had been controlled by Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire, for many years a rival of Pope Innocent IV.[246] On Frederick's death in 1250, Innocent started to look for a new ruler, one more amenable to the Papacy.[247] Henry saw Sicily as both a valuable prize for his son and as an excellent base for his crusading plans in the east.[248] With minimal consultation within his court, Henry came to an agreement with the Pope in 1254 that Edmund should be the next king.[249] Innocent urged Henry to send Edmund with an army to reclaim Sicily from Frederick's son Manfred, offering to contribute to the expenses of the campaign.[250]

Innocent was succeeded by Pope Alexander IV, who was facing increasing military pressure from the Empire.[251] He could no longer afford to pay Henry's expenses, instead demanding that Henry compensate the Papacy for the £90,000 spent on the war so far.[251][lower-alpha 8] This was a huge sum, and Henry turned to parliament for help in 1255, only to be rebuffed. Further attempts followed, but by 1257 only partial parliamentary assistance had been offered.[252]

Alexander grew increasingly unhappy about Henry's procrastinations and in 1258 sent an envoy to England, threatening to excommunicate Henry if he did not first pay his debts to the Papacy and then send the promised army to Sicily.[253] Parliament again refused to assist the King in raising this money.[254] Instead Henry turned to extorting money from the senior clergy, who were forced to sign blank charters, promising to pay effectively unlimited sums of money in support of the King's efforts, raising around £40,000.[255][lower-alpha 8] The English Church felt the money was wasted, vanishing into the long-running war in Italy.[256]

Meanwhile, Henry attempted to influence the outcomes of the elections in the Holy Roman Empire, which would appoint a new King of the Romans.[257] When the more prominent German candidates failed to gain traction, Henry began to back his brother Richard's candidature, giving donations to his potential supporters in the Empire.[258] Richard was elected in 1256 with expectations of possibly being crowned the Holy Roman Emperor, but continued to play a major role in English politics.[259] His election faced a mixed response in England; Richard was believed to provide moderate, sensible counsel and his presence was missed by the English barons, but he also faced criticism, probably incorrectly, for funding his German campaign at England's expense.[260] Although Henry now had increased support in the Empire for a potential alliance against Louis of France, the two kings were now moving towards potentially settling their disputes peacefully; for Henry, a peace treaty could allow him to focus on Sicily and his crusade.[261]

Later reign (1258–1272)

Revolution

In 1258, Henry faced a revolt among the English barons.[262] Anger had grown about the way the King's officials were raising funds, the influence of the Poitevins at court and his unpopular Sicilian policy, and resentment of abuse of purchased Jewish loans.[164] Even the English Church had grievances over its treatment by the King.[263] The Welsh were still in open revolt, and now allied themselves with Scotland.[7]

Henry was also critically short of money. Although he still had some reserves of gold and silver, they were totally insufficient to cover his potential expenditures, including the campaign for Sicily and his debts to the Papacy.[264] Critics suggested darkly that he had never really intended to join the crusades, and was simply intending to profit from the crusading tithes.[265] To compound the situation, the harvests in England failed.[7] Within Henry's court there was a strong feeling that the King would be unable to lead the country through these problems.[266]

The discontent finally erupted in April, when seven of the major English and Savoyard barons – Simon de Montfort, Roger and Hugh Bigod, John Fitzgeoffrey, Peter de Montfort, Peter de Savoy and Richard de Clare – secretly formed an alliance to expel the Lusignans from court, a move probably quietly supported by the Queen.[267] On 30 April, Roger Bigod marched into Westminster in the middle of the King's parliament, backed by his co-conspirators, and carried out a coup d'état.[268] Henry, fearful that he was about to be arrested and imprisoned, agreed to abandon his policy of personal rule and instead govern through a council of 24 barons and churchmen, half chosen by the King and half by the barons.[269] His own nominees to the council drew heavily on the hated Lusignans.[270]

The pressure for reform continued to grow unabated and a fresh parliament met in June, passing a set of measures known as the Provisions of Oxford, which Henry swore to uphold.[271] These provisions created a smaller council of 15 members, elected solely by the barons, which then had the power to appoint England's justiciar, chancellor, and treasurer, and which would be monitored through triannual parliaments.[272][lower-alpha 29] Pressure from the lesser barons and the gentry present at Oxford also helped to push through wider reform, intended to limit the abuse of power by both Henry's officials and the major barons.[274] The elected council included representatives of the Savoyard faction but no Poitevins, and the new government immediately took steps to exile the leading Lusignans and to seize key castles across the country.[275]

The disagreements between the leading barons involved in the revolt soon became evident.[276] Simon championed radical reforms that would place further limitations on the authority and power of the major barons as well as the Crown; others, such as Hugh Bigod, promoted only moderate change, while the conservative barons, such as Richard, expressed concerns about the existing limitations on the King's powers.[277] Henry's son, Edward, initially opposed the revolution, but then allied himself with de Montfort, helping him to pass the radical Provisions of Westminster in 1259, which introduced further limits on the major barons and local royal officials.[278]

Crisis

Over the next four years, neither Henry nor the barons were able to restore stability in England, and power swung back and forth between the different factions.[279] One of the priorities for the new regime was to settle the long-running dispute with France and, at the end of 1259, Henry and Eleanor left for Paris to negotiate the final details of a peace treaty with King Louis, escorted by Simon de Montfort and much of the baronial government.[280] Under the treaty, Henry gave up any claim to his family's lands in the north of France, but was confirmed as the legitimate ruler of Gascony and various neighbouring territories in the south, giving homage and recognising Louis as his feudal lord for these possessions.[281]

When Simon de Montfort returned to England, Henry, supported by Eleanor, remained in Paris where he seized the opportunity to reassert royal authority and began to issue royal orders independently of the barons.[282] Henry finally returned to retake power in England in April 1260, where conflict was brewing between Richard de Clare's forces and those of Simon and Edward.[283] Henry's brother Richard mediated between the parties and averted a military confrontation; Edward was reconciled with his father and Simon was put on trial for his actions against the King.[284] Henry was unable to maintain his grip on power, and in October a coalition headed by Simon, Richard and Edward briefly seized back control; within months their baronial council had collapsed into chaos as well.[285]

Henry continued publicly to support the Provisions of Oxford, but he secretly opened discussions with Pope Urban IV, hoping to be absolved from the oath he had made at Oxford.[286] In June 1261, the King announced that Rome had released him from his promises and he promptly held a counter-coup with the support of Edward.[287] He purged the ranks of the sheriffs of his enemies and seized back control of many of the royal castles.[287] The baronial opposition, led by Simon and Richard, were temporarily reunited in their opposition to Henry's actions, convening their own parliament, independent of the King, and establishing a rival system of local government across England.[288] Henry and Eleanor mobilised their own supporters and raised a foreign mercenary army.[289] Facing the threat of open civil war, the barons backed down: de Clare switched sides once again, Simon left for exile in France and the baronial resistance collapsed.[289]

Henry's government relied primarily on Eleanor and her Savoyard supporters, and it proved short-lived.[290] He attempted to settle the crisis permanently by forcing the barons to agree to the Treaty of Kingston.[291] This treaty introduced a system of arbitration to settle outstanding disputes between the King and the barons, using Richard as an initial adjudicator, backed up by Louis of France should Richard fail to generate a compromise.[292] Henry softened some of his policies in response to the concerns of the barons, but he soon began to target his political enemies and recommence his unpopular Sicilian policy.[293] He had done nothing significant to deal with the concerns over Baronial and royal abuse of Jewish debts.[168]

Henry's government was weakened by the death of Richard, as his heir, Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester, sided with the radicals; the King's position was further undermined by major Welsh incursions along the Marches and the Pope's decision to reverse his judgement on the Provisions, this time confirming them as legitimate.[294] By early 1263, Henry's authority had disintegrated and the country slipped back towards open civil war.[295]

Second Barons' War

Simon returned to England in April 1263 and convened a council of rebel barons in Oxford to pursue a renewed anti-Poitevin agenda.[296] Revolt broke out shortly afterwards in the Welsh Marches and, by October, England faced a likely civil war between Henry, backed by Edward, Hugh Bigod and the conservative barons, and Simon, Gilbert de Clare and the radicals.[297] The rebels leveraged concern among knights over abuse of Jewish loans, who feared losing their lands, a problem Henry had done much to create and nothing to solve.[298] In each case following, the rebels employed violence and killings in a deliberate attempt to destroy the records of their debts to Jewish lenders.[299]

Simon marched east with an army and London rose up in revolt, where 500 Jews died.[300] Henry and Eleanor were trapped in the Tower of London by the rebels. The Queen attempted to escape up the River Thames to join Edward's army at Windsor, but was forced to retreat by the London crowds.[301] Simon took the pair prisoners, and although he maintained a fiction of ruling in Henry's name, the rebels completely replaced the royal government and household with their own trusted men.[302]

Simon's coalition quickly began to fragment, Henry regained his freedom of movement and renewed chaos spread across England.[303] Henry appealed to Louis of France for arbitration in the dispute, as had been laid out in the Treaty of Kingston; Simon was initially hostile to this idea, but, as war became more likely again, he decided to agree to French arbitration as well.[304] Henry went to Paris in person, accompanied by Simon's representatives.[305] Initially Simon's legal arguments held sway, but in January 1264, Louis announced the Mise of Amiens, condemning the rebels, upholding the King's rights and annulling the Provisions of Oxford.[306] Louis had strong views of his own on the rights of kings over those of barons, but was also influenced by his wife, Margaret, who was Eleanor's sister, and by the Pope.[307][lower-alpha 30] Leaving Eleanor in Paris to assemble mercenary reinforcements, Henry returned to England in February 1264, where violence was brewing in response to the unpopular French decision.[309]

The Second Barons' War finally broke out in April 1264, when Henry led an army into Simon's territories in the Midlands, and then advanced south-east to re-occupy the important route to France.[310] Becoming desperate, Simon marched in pursuit of Henry and the two armies met at the Battle of Lewes on 14 May.[311] Despite their numerical superiority, Henry's forces were overwhelmed.[312] His brother Richard was captured, and Henry and Edward retreated to the local priory and surrendered the following day.[312] Henry was forced to pardon the rebel barons and reinstate the Provisions of Oxford, leaving him, as historian Adrian Jobson describes, "little more than a figurehead".[313] With Henry's power diminished, Simon cancelled many debts and interest owed to Jews, including those held by his baronial supporters.[314][lower-alpha 31]

Simon was unable to consolidate his victory and widespread disorder persisted across the country.[316] In France, Eleanor made plans for an invasion of England with the support of Louis, while Edward escaped his captors in May and formed a new army with Gilbert de Clare, who switched sides to the royal government.[317] He pursued Simon's forces through the Marches, before striking east to attack his fortress at Kenilworth and then turning once more on the rebel leader himself.[318] Simon, accompanied by the captive Henry, was unable to retreat and the Battle of Evesham ensued.[319]

Edward was triumphant and Simon's corpse was mutilated by the victors. Henry, who was wearing borrowed armour, was almost killed by Edward's forces during the fighting before they recognised the King and escorted him to safety.[320] In places the now leaderless rebellion dragged on, with some rebels gathering at Kenilworth Castle, which Henry and Edward took after a long siege in 1266.[321] They continued targeting Jews and their debt records.[298] The remaining pockets of resistance were mopped up, and the final rebels, holed up in the Isle of Ely, surrendered in July 1267, marking the end of the war.[322]

Reconciliation and reconstruction

Henry quickly took revenge on his enemies after the Battle of Evesham.[323] He immediately ordered the sequestration of all the rebel lands, triggering a wave of chaotic looting across the country.[324] Henry initially rejected any calls for moderation, but in October 1266 he was persuaded by Papal Legate Ottobuono de' Fieschi to issue a less draconian policy, called the Dictum of Kenilworth, which allowed for the return of the rebels' lands, in exchange for the payment of harsh fines.[325] The Statute of Marlborough followed in November 1267, which effectively reissued much of the Provisions of Westminster, placing limitations on the powers of local royal officials and the major barons, but without restricting central royal authority.[326] Most of the exiled Poitevins began to return to England after the war.[327] In September 1267 Henry made the Treaty of Montgomery with Llywelyn, recognising him as the Prince of Wales and giving substantial land concessions.[328]

In the final years of his reign, Henry was increasingly infirm and focused on securing peace within the kingdom and his own religious devotions.[329] Edward became the Steward of England and began to play a more prominent role in government.[330] Henry's finances were in a precarious state as a result of the war, and when Edward decided to join the crusades in 1268 it became clear that fresh taxes were necessary.[326] Henry was concerned that Edward's absence might encourage further revolts, but was swayed by his son to negotiate with multiple parliaments over the next two years to raise the money.[331]

Although Henry had initially reversed Simon de Montfort's anti-Jewish policies, including attempting to restore the debts owed to Jews where these could be proven, he faced pressure from parliament to introduce restrictions on Jewish bonds, particularly their sale to Christians, in the final years of his reign in return for financing.[332][lower-alpha 32] Henry continued to invest in Westminster Abbey, which became a replacement for the Angevin mausoleum at Fontevraud Abbey, and in 1269 he oversaw a grand ceremony to rebury Edward the Confessor in a lavish new shrine, personally helping to carry the body to its new resting place.[333]

Death

Edward left for the Eighth Crusade, led by Louis of France, in 1270, but Henry became increasingly ill; concerns about a fresh rebellion grew and the next year the King wrote to his son asking him to return to England, but Edward did not turn back.[334] Henry recovered slightly and announced his renewed intention to join the crusades himself, but he never regained his full health and on the evening of 16 November 1272, he died in Westminster, probably with Eleanor in attendance.[335] He was succeeded by Edward, who slowly made his way back to England via Gascony, finally arriving in August 1274.[336]

At his request, Henry was buried in Westminster Abbey in front of the church's high altar, in the former resting place of Edward the Confessor.[337][lower-alpha 33] A few years later, work began on a grander tomb for Henry and in 1290 Edward moved his father's body to its current location in Westminster Abbey.[339] His gilt-brass tomb effigy was designed and forged within the abbey grounds by William Torell; unlike other effigies of the period, it is particularly naturalistic in style, but it is probably not a close likeness of Henry himself.[340][lower-alpha 34]

Eleanor probably hoped that Henry would be recognised as a saint, as his contemporary Louis IX of France had been; indeed, Henry's final tomb resembled the shrine of a saint, complete with niches possibly intended to hold relics.[342] When the King's body was exhumed in 1290, contemporaries noted that the body was in perfect condition and that Henry's long beard remained well preserved, which at the time was considered to be an indication of saintly purity.[343] Miracles began to be reported at the tomb, but Edward was sceptical about these stories. The reports ceased, and Henry was never canonised.[344] In 1292, his heart was removed from his tomb and reburied at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou, France with the bodies of his Angevin family.[339]

Legacy

Historiography

.jpg.webp)

The first histories of Henry's reign emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries, relying primarily on the accounts of medieval chroniclers, in particular writings of Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris.[7] These early historians, including Archbishop Matthew Parker, were influenced by contemporary concerns about the roles of the Church and state, and examined the changing nature of kingship under Henry, the emergence of English nationalism during the period and what they perceived to be the malign influence of the Papacy.[345] During the English Civil War, historians also drew parallels between Henry's experiences and those of the deposed Charles I.[346]

By the 19th century, Victorian scholars such as William Stubbs, James Ramsay, and William Hunt sought to understand how the English political system had evolved under Henry.[7] They explored the emergence of Parliamentary institutions during his reign, and sympathized with the concerns of the chroniclers over the role of the Poitevins in England.[7] This focus carried on into early 20th-century research into Henry, such as Kate Norgate's 1913 volume, which continued to make heavy use of the chronicler accounts and focused primarily on constitutional issues, with a distinctive nationalistic bias.[347]

After 1900, the financial and official records from Henry's reign began to become accessible to historians, including the pipe rolls, court records, correspondence and records of administration of the royal forests.[348] Thomas Frederick Tout made extensive use of these new sources in the 1920s, and post-war historians brought a particular focus on the finances of Henry's government, highlighting his fiscal difficulties.[349] This wave of research culminated in Sir Maurice Powicke's two major biographical works on Henry, published in 1948 and 1953, which formed the established history of the King for the next three decades.[350]

Henry's reign did not receive much attention from historians for many years after the 1950s: no substantial biographies of Henry were written after Powicke's, and the historian John Beeler observed in the 1970s that the coverage of Henry's reign by military historians remained particularly thin.[351] At the end of the 20th century, there was a renewed interest in 13th-century English history, resulting in the publication of various specialist works on aspects of Henry's reign, including government finance and the period of his minority.[7] Current historiography notes both Henry's positive and negative qualities: historian David Carpenter judges him to have been a decent man, who failed as a ruler because of his naivety and inability to produce realistic plans for reform, a theme echoed by Huw Ridgeway, who also notes his unworldliness and inability to manage his court, but who considers him to have been "essentially a man of peace, kind and merciful".[352]

Popular culture

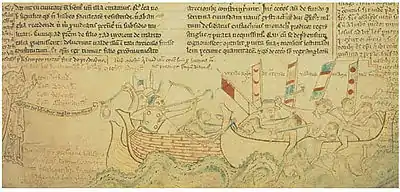

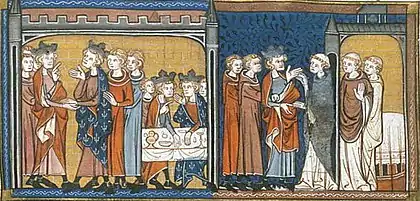

The chronicler Matthew Paris depicted Henry's life in a series of illustrations, which he sketched and, in some cases, water-coloured, in the margins of the Chronica Majora.[353] Paris first met Henry in 1236 and enjoyed an extended relationship with the King, although he disliked many of Henry's actions and the illustrations are frequently unflattering.[354]

Henry is a character in Purgatorio, the second part of Dante's Divine Comedy (completed in 1320). The King is depicted sitting alone in purgatory, to one side of other failed rulers:[355] Rudolf I of Germany, Ottokar II of Bohemia, Philip III of France and Henry I of Navarre, as well as Charles I of Naples and Peter III of Aragon. Dante's symbolic intent in depicting Henry sitting separately is unclear; possible explanations include it being a reference to England not being part of the Holy Roman Empire and/or it indicating that Dante had a favourable opinion of Henry, due to his unusual piety.[355] His son, Edward, is also saluted by Dante in this work (Canto VII. 132).

Henry appears in King John by William Shakespeare as a minor character referred to as Prince Henry but within modern popular culture, Henry has a minimal presence and has not been a prominent subject of films, theatre or television.[356] Historical novels which feature him as a character include Longsword, Earl of Salisbury: An Historical Romance (1762) by Thomas Leland,[357] The Red Saint (1909) by Warwick Deeping,[358] The Outlaw of Torn (1927) by Edgar Rice Burroughs, The De Montfort Legacy (1973) by Pamela Bennetts, The Queen from Provence (1979) by Jean Plaidy, The Marriage of Meggotta (1979) by Edith Pargeter and Falls the Shadow (1988) by Sharon Kay Penman.[359]

Issue

Henry and Eleanor had five children:[lower-alpha 25]

- Edward I (b. 17/18 June 1239 – d. 7 July 1307)[184]

- Margaret (b. 29 September 1240 – d. 26 February 1275)[184]

- Beatrice (b. 25 June 1242 – d. 24 March 1275)[184]

- Edmund (16 January 1245 – d. 5 June 1296)[184]

- Katherine (b. 25 November 1253 – d. 3 May 1257)[184]

Henry had no known illegitimate children.[360]

Family tree

| Henry III and his family[361] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- The description of Henry's eyelid, written after his death, comes from the chronicler Nicholas Trevet. Measurements of Henry's coffin in the 19th century indicate a height of 1.68 metres (5 ft 6 in).[7]

- It was not particularly unusual for rulers in the early 13th century to give homage to the Pope in this way: Richard I had done similarly, as had the rulers of Aragon, Denmark, Poland, Portugal, Sicily and Sweden.[13]

- Henry's speedy coronation was intended to draw a clear distinction between the young king and his rival Louis, who had only been elected by the barons and was never crowned.[18]

- Initially William Marshal termed himself the King's justiciar. When Hubert de Burgh, the existing justiciar, complained, William altered his title to the rector nostrer et rector nostri, "our ruler and the ruler of our kingdom".[28]