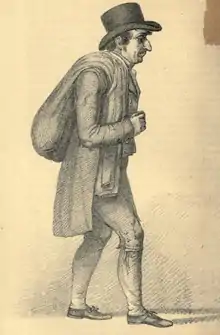

Henry Lemoine (writer)

Henry Lemoine (1756–1812) was an English author and bookseller.

Early life

From a Huguenot background, he was born in Spitalfields 14 January 1756, and baptised in the French church De La Patente in Brown's Lane there, 1 February 1756. He was the only son of Henry Lemoine who had left Normandy for Jersey, who died in April 1760; his mother, Anne I. Cenette, was a native of Guernsey. He was educated at a free school run French Calvinists in the East End of London, and in 1770 was apprenticed to a stationer and rag merchant in Lamb Street, Spitalfields.[1]

From Spitalfields Lemoine moved about 1773 to the shop of a Mr. Chatterton, a baker and bookseller. He then became for a time French master in a boarding-school at Vauxhall, kept by one Mannypenny, a post lost by the hoax that he was incapable of speaking a word of English. On coming of age in 1777 he inherited property in Jersey, purchased a bookstall in the Little Minories, and began writing for magazines. He also dispensed drugs, including the "bug-water" of Thomas Marryat's recipe.[1]

In 1780 Lemoine moved to a stand in the churchyard at Bishopsgate, Churchyard, and became acquainted with David Levi the Jewish apologist, whom he supplied with materials for his controversy with Joseph Priestley. About this period he met with Levi and other writers at the house of George Lackington in Chiswell Street. On 8 October 1788 he was admitted a freeman of the Leathersellers Company by redemption.[1]

Editor and bookseller

In 1792 Lemoine started the Conjurors' Magazine, with embodied a translation of the treatise on physiognomy by Johann Kaspar Lavater. It sold well, but by 1793, when it became known as the Astrologer's Magazine, Lemoine's connection with it had practically ceased; it did include reprints of some stories of his from the Arminian Magazine and elsewhere. In 1793 he started the Wonderful Magazine and Marvellous Chronicle, to which he contributed biographies including one of Baron Diego Pereira d'Aguilar.[1]

In 1794 Lemoine was in the copperplate printing business, but lost heavily, was imprisoned for debt, and separated from his wife. In 1795 he had to give up his bookshop,[2] and peddled pamphlets and chapbooks. Simultaneously he did much hack-work, translation and compilation for London booksellers. eventually becoming the recognised doyen of his profession.[1]

Later life

About 1807 Lemoine again set up in business, with a small bookstand in Parliament Street a small stand of books. Towards the end of his life he lived in the house of a Mr. Broom in Drury Lane, but he was still active with his pen, and started the Eccentric Magazine, before the conclusion of the first volume of which he died on 30 April 1812 in St. Bartholomew's Hospital. He had a reputation as careless with money and a drinker. His studies were generally carried on in the street, and his books written on loose papers in public houses.[1]

Works

Lemoine's major work was published in 1797, Typographical Antiquities.[3] There was a second edition, with slightly altered title, 1801.[1]

While with Chatterton, Lemoine wrote for an amateur dramatic club two satirical pieces in the manner of Charles Churchill, The Stinging Nettle and The Reward of Merit. Extracts from the latter appeared in The London Magazine, July and August 1780. Under the pseudonym "Allan Macleod" he attacked George Lackington in his ironical Lackington's Confessions rendered into Narrative (1804).[1]

In 1786 Lemoine published anonymously The Kentish Curate, or the History of Lamuel Lyttleton, an improper narrative romance in four volume. About this time he also issued a reprint of John Cleland's pornographic Fanny Hill. In 1790 he published a rhymed version of Robert Blair's The Grave. In 1791 he compiled Visits from the World of Spirits, or interesting anecdotes of the Dead … containing narratives of the appearances of many departed spirits; a second edition was published (Glasgow, 1845). In 1793 he edited a herbal on the lines of Nicholas Culpeper's, The Medical Uses of English Plants.[1]

In 1795 Lemoine supplied much verse on Charlotte and Werther to the Lady's New and Elegant Pocket Magazine. From 1803 to 1806, he was working on the bibliographical dictionary of Adam Clarke. He wrote a pseudonymous life of Abraham Goldsmid; most of his works were anonymous, and others may not be easily identified., He was a frequent contributor to the Gentleman's Magazine, and wrote odes on other hack writers, listed in William Granger's New Wonderful Museum.[1]

Family

He married the Gothic chapbook publisher, Ann Lemoine on 8 January 1786.[4] They had two children.[5]

Notes

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 33. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Goldthorpe, David (2004). "Lemoine, Henry (1756–1812), author and bookseller". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16430. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Typographical Antiquities: the History, Origin, and Progress of the Art of Printing … also a … complete History of the Walpolean Press … at Strawberry Hill … a … Dissertation on the Origin and Use of Paper … a … History of the Art of Wood-cutting and Engraving on Copper with the Adjudication of Literary Property … a Catalogue of remarkable Bibles and Common Prayer Books, etc., pp. 156, London.

- The History of Gothic Publishing, 1800-1835: Exhuming the Trade. p. 58. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Potter, Franz J. (2013). "Lemoine, Ann". In William Hughes; David Punter; Andrew Smith (eds.). The Encyclopedia of the Gothic. Wiley Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781118398500.wbeotgl004. ISBN 9781118398500.

Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). "Lemoine, Henry". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 33. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). "Lemoine, Henry". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 33. London: Smith, Elder & Co.