Henri Estienne

Henri Estienne (/eɪˈtjɛn/ ay-TYEN, French: [ɑ̃ʁi etjɛn]; 1528 or 1531 – 1598), also known as Henricus Stephanus (/ˈstɛfənəs/ STEF-ən-əs), was a French printer and classical scholar. He was the eldest son of Robert Estienne. He was instructed in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew by his father and would eventually take over the Estienne printing firm which his father owned in 1559 when his father died. His most well-known work was the Thesaurus graecae linguae, which was printed in five volumes. The basis of Greek lexicology, no thesaurus would rival that of Estienne's for three hundred years.

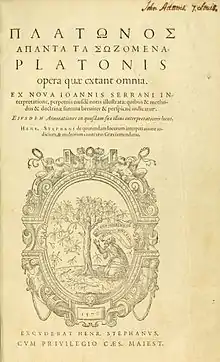

Among his many publications of Greek authors, his publications of Plato are the source of Stephanus pagination, which is still used to refer to Plato's works. Estienne died in Lyon in 1598.

Life

Henri Estienne was born in Paris in 1528 or 1531.[1][note 1] His father instructed him in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and typography,[2] and according to a note in his edition of Aulus Gellius (1585), he picked up some Latin as a child, as that language was used as a lingua franca in the multi-national household.[3] However, he was primarily instructed in Greek by Pierre Danès.[4] He was also educated by other French scholars such as Adrianus Turnebus.[5] He began working for his father's business at age eighteen[6] and was employed by his father to collate a manuscript of Dionysius of Halicarnassus.[3] In 1547, as part of his training, he traveled to Italy, England, and Flanders, where he learned Spanish[3] and busied himself in collecting and collating manuscripts for his father's press.[7] Around 1551, Robert Estienne fled to Geneva with his family, including Henri Estienne, to escape religious persecution in Paris.[8] The same year, he translated Calvin's catechism into Greek,[9] which was printed in 1554 in his father's printing room.[7]

Estienne published the Anacreon in 1554, which was his first independent work.[10] Afterwards, he returned to Italy to assist the Aldine Press in Venice. In Italy, he discovered a copy of Diodorus Siculus in Rome, and returned to Geneva in 1555.[7] In 1557 he likely had a printing establishment of his own, advertising himself as the "Parisian printer" (typographus parisiensis).[7] The following year he assumed the title illustris viri Huldrici Fuggeri typographus from his patron, Ulrich Fugger who saved him from financial despair after the death of his father.[11] Estienne published the first anthology that included sections from Parmenides, Empedocles, and other Pre-Socratic philosophers.[2]

In 1559, on his father's death, Estienne assumed charge of his presses and became Printer of the Republic of Geneva.[12] In the same year he produced his own Latin translation of the works of Sextus Empiricus, and an edition of Diodorus Siculus based on his earlier discoveries.[3] In 1565, he printed a large French Bible.[13] The following year he published his best-known French work, the Apologie pour Hérodote. Some passages being considered objectionable by the Geneva consistory, he was compelled to cancel the pages containing them. The book became highly popular, and within sixteen years twelve editions were printed.[3] Estienne used the type he inherited and did not invent any new types.[2]

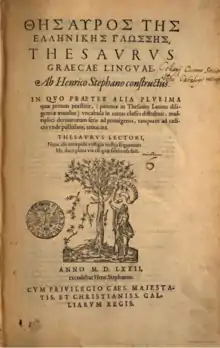

His most celebrated work, the Thesaurus graecae linguae or Greek thesaurus, appeared in five volumes in 1572.[14] This thesaurus was a sequel to Robert Estienne's Latin thesaurus. The basis of Greek lexicography, a Greek thesaurus to rival that of Estiennes was not printed for over 300 years.[15] This work was begun by his father and served up to the nineteenth century as the basis of Greek lexicography. However, the sale of this thesaurus was impeded due to its high price and the printing of an abridged copy later.[6] In 1576 and 1587, Estienne published two Greek versions of the New Testament. The 1576 version contained the first scientific treatise on the language of the apostolic writers. The 1587 version contained a discussion on the ancient divisions of the text.[16] Estienne's other publications included those of Herodotus, Plato, Horace, Virgil, Plutarch, and Pliny the Elder.[6] He also published an edition of Aeschylus, in which Agamemnon was printed in its entirety and as a separate play for the first time.[3]

In 1578 he published the first and one of the most important editions of the complete works of Plato, translated by Jean de Serres, with commentary. This work is the source of the standard "Stephanus numbers" used by scholars today to refer to the works of Plato.[5]

The publication in 1578 of his Deux Dialogues du nouveau françois italianizé brought him into a fresh dispute with the consistory. To avoid their censure he went to Paris, and resided at the French court for a year. On his return to Geneva he was summoned before the consistory and was imprisoned for a week. From this time his life became more and more nomadic. He traveled to Basel, Heidelberg, Vienna, and Pest.[17] He also spent time in Paris and other regions in France.[6] These journeys were undertaken partly in the hope of procuring patrons and purchasers, for the large sums which he had spent on such publications as the Thesaurus and the Plato of 1578 had almost ruined him.[18] He published a concordance of the New Testament in 1594.[16]

After visiting the University of Montpellier, where Isaac Casaubon, his son-in-law, was now professor, he started for Paris. He was taken ill in Lyon, and died there at the end of January 1598.[18][19]

Family

Henri Estienne was married three times. He married Marguerite Pillot in 1555, Barbe de Wille in 1556, and Abigail Pouppart in 1586.[19] Estienne had fourteen children, three of whom survived him.[20] His daughter was married to Isaac Casaubon.[6] His son Paul (born 1567) assumed control of the presses in Geneva with Casaubon but he fled to Paris from the authorities.[20] Paul's son Antoine became "Printer to the King" in Paris and "Guardian of the Greek Matrices"; however his death in 1674 ended the nearly two-century-long Estienne printing business.[20]

Legacy

Henri Estienne is considered by some scholars to be the most prominent printer in the Estienne family.[6] Estienne was one of the "greatest and last scholarly editors and publishers of the Renaissance."[2]

External links

- Collection of links to online scans of the Thesaurus graecae linguae in the "Links Galore" spreadsheet

See also

- Stephanus pagination

- Jean de Serres, collaborator on Plato edition

- Comparison of Ancient Greek dictionaries

Footnotes

- Sources have conflicting information about whether he was born in 1528 or 1531.

Citations

- Busby 1993, p. 126;Considine 2000, p. 208

- Amert 2012, p. 16.

- Tilley 1911, p. 799.

- Armstrong 1986, p. 61.

- Reverdin 1956, p. 239.

- Thomas 1870, p. 938.

- Schaff 1884, p. 2242.

- Reverdin 1956, p. 240.

- Cross 1966, p. 11.

- Morrison 1962, p. 391.

- Reverdin 1956, p. 239;Considine 2008, p. 93

- Estienne, Henri, in the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Pettegree, Walsby & Wilkinson 2007, p. 128.

- Grafton, Most & Settis 2010, p. 331.

- Amert 2012, p. 16; Schaff 1884, p. 2242

- Simon & Hunwick 2013, p. xvii.

- Tilley 1911, pp. 799–800.

- Tilley 1911, p. 800.

- Busby 1993, p. 126.

- Steinberg 2017, p. 64.

References

- Amert, Kay (2012). Bringhurst, Robert (ed.). 'The Scythe and the Rabbit: Simon de Colines and the Culture of the Book in the Renaissance Paris. Rochester, New York: Cary Graphic Arts Press. ISBN 9781933360560. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- Armstrong, Elizabeth (1986). Robert Estienne, Royal Printer: An Historical Study of the Elder Stephanus (Revised ed.). The Sutton Courtenay Press. ISBN 978-0900721236.

- Busby, Keith, ed. (1993). Les Manuscrits de Chrétien de Troyes. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 978-9051836134. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Considine, John (2008). Dictionaries in Early Modern Europe: Lexicography and the Making of Heritage. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521886741. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Considine, John (Spring 2000). "The Lexicographer as Hero: Samuel Johnson and Henri Estienne". Philological Quarterly. 79 (2): 205–224. ProQuest 211158267.

- Cross, Claire (1966). The Puritan Earl: The Life of Henry Hastings, Third Earl of Huntingdon 1536-1595. New York: St. Martin's Press Inc. ISBN 9781349000920. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore, eds. (2010). The Classical Tradition. Cambridge Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674035720. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- Louis Gabriel Michaud. "Henri Estienne". Biographie universelle ancienne et moderne : histoire par ordre alphabétique de la vie publique et privée de tous les hommes avec la collaboration de plus de 300 savants et littérateurs français ou étrangers (in French) (2 ed.).

- Morrison, Mary (1962). "Henri Estienne and Sappho". Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et Renaissance. 24 (2): 388–391. JSTOR 20674384.

- Pettegree, Andrew; Walsby, Malcolm; Wilkinson, Alexander, eds. (2007). French Vernacular Books: Books Published in the French Language before 1601. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004163232. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- Reverdin, Olivier (1956). "Le "Platon" d'Henri Estienne". Museum Helveticum. 13 (4): 239–250. JSTOR 24812617.

- Schaff, Philip, ed. (1884). A Religious Encyclopaedia: Or Dictionary of Biblical, Historical, Doctrinal and Practical Theology. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Simon, Richard; Hunwick, Andrew (2013). Critical History of the Text of the New Testament: Wherein is Established the Truth of the Acts on which the Christian Religion is Based. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004244207. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- Steinberg, S.H. (2017). Five Hundred Years of Printing. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 9780486814452. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Thomas, Joseph (1870). Universal Pronouncing Dictionary of Biography and Mythology. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- Tilley, Arthur Augustus (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 798–800. This includes a detailed assessment of his work by the author.