Heraclio Bernal

Heraclio Bernal (1855-1888) was a bandit from the Sinaloa region of Mexico. He is widely known as the "Thunderbolt of Sinaloa."[1][2][3][4]

Heraclio Bernal | |

|---|---|

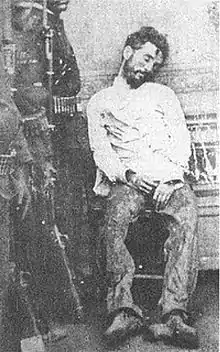

Bernal's body | |

| Born | 1855 |

| Died | 1888 |

| Other names | "Thunderbolt of Sinaloa" |

| Occupation | revolutionary |

| Criminal charge | Banditry |

Bandit years

Bernal led a group of pistoleros, who operated along the mining zones of the Sierra Madre Occidental, dominating parts of Sinaloa and Durango.[4] The band was believed to have reached up to 100 men strong, often participating in illegal acts such as; robbing stagecoaches, attacking armories, raiding mines for silver which was later sold, and stealing from the rich residents of towns he raided. During Bernal's ten year stint as a bandit and as a political rebel, he managed to evade capture repeatedly due to his established good relations with the lower class and important people of the region he operated within. It is also believed police and soldiers would sell Bernal, and other bandits, weapons and ammunition.[1][3]

Throughout Bernal's career he was heavily pursued by the local governor Francisco Cañedo, often challenging and mocking him. Stories exist of Bernal challenging Cañedo and President Porfirio Díaz. When Diaz held a dinner for local dignitaries, Bernal is said to have countered with an even more lavish dinner in a neighboring town. While the stories are in doubt, they led to Bernal being viewed as a hero by the people of the surrounding villages.[1]

At some point, probably in 1883, Bernal's group was joined by five of the Parra brothers, including Ignacio Parra whose gang would absorb many of Bernal's members following his death.[3]

In 1885 Bernal attempted to enter government service and sent word to president Díaz of an offer. In exchange for service as an officer, Bernal wanted 30,000 pesos to finance himself and his security. He also demanded the release of any of his captured gang members, including his imprisoned brother. Díaz refused the offer, though it is believed Bernal could have received a pardon had he not requested such a high payment.[1]

Politics and death

In 1887 Bernal entered the role of a political rebel, creating a platform which called for a return to the 1857 Constitution of Mexico, which had barred repeated re-elections of the same candidate. The move to enact such a policy was past its time, as many of those who would have backed Bernal now preferred to have Díaz repeatedly re-elected to maintain control.[1]

In time the government would move soldiers into the Mazatlán region and form anti-guerrilla forces to track down Bernal. A ransom of 10,000 pesos was placed on the capture of Bernal, and he was soon after set up in an ambush by two of his gang members. Bernal died on January 5, 1888.

Ballads/Corridos

Over thirty corridos or folk ballads exist placing Bernal in the role of a hero and promoting his exploits. One of the more popular involves changing of the colors of the horse Bernal is riding on and the features of description:[5]

|

Que rechulo era Bernal, |

How beautiful was Bernal, |

Aspects of Bernal's life may have evolved into the folk-saint Jesús Malverde.[6]

References

- Vanderwood, Paul J. (1992). Disorder and Progress: Bandits, Police, and Mexican Development. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 207, 11, 44, 93. ISBN 0-8420-2439-5.

- Lomax, John A. (2007). American Ballads & Folk Songs (1934). READ BOOKS. p. 368. ISBN 978-1-4067-5090-4.

- Katz, Friedrich (1998). The Life and Times of Pancho Villa. Stanford University Press. pp. 68. ISBN 0-8047-3046-6.

- Hamnett, Brian R. (25 November 1999). A Concise History of Mexico. Cambridge University Press. pp. 178. ISBN 0-521-58916-9.

- Paredes, Américo (1970). With His Pistol in His Hand: a border ballad and its hero. University of Texas Press. p. 233. ISBN 0-292-70128-4.

- Quinones, Sam, True Tales from Another Mexico: The Lynch Mob, the Popsicle Kings, Chalino, and the Bronx, UNM Press, 2001, p.227