Herbert Hope Risley

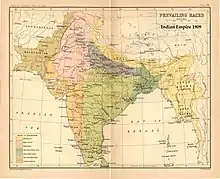

Sir Herbert Hope Risley KCIE CSI FRAI (4 January 1851 – 30 September 1911) was a British ethnographer and colonial administrator, a member of the Indian Civil Service who conducted extensive studies on the tribes and castes of the Bengal Presidency. He is notable for the formal application of the caste system to the entire Hindu population of British India in the 1901 census, of which he was in charge. As an exponent of scientific racism, he used anthropometric data to divide Indians into seven races.[1][2]

Risley was born in Buckinghamshire, England, in 1851 and attended New College, Oxford University prior to joining the Indian Civil Service (ICS). He was initially posted to Bengal, where his professional duties engaged him in statistical and ethnographic research, and he soon developed an interest in anthropology. His decision to indulge these interests curtailed his initial rapid advancement through the ranks of the Service, although he was later appointed Census Commissioner and, shortly before his death in 1911, became Permanent Secretary at the India Office in London. In the intervening years he compiled various studies of Indian communities based on ideas that are now considered to constitute scientific racism. He emphasised the value of fieldwork and anthropometric studies, in contrast to the reliance on old texts and folklore that had historically been the methodology of Indologists and which was still a significant approach in his lifetime.

Aside from being honoured by his country, including by the award of a knighthood, Risley also became President of the Royal Anthropological Institute.

Early life

Herbert Hope Risley was born at Akeley in Buckinghamshire, England, on 4 January 1851. His father was a rector and his mother the daughter of John Hope, who had served in the Bengal Medical Service at Gwalior.[3]

During his schooldays at Winchester College, where many of his relatives had preceded him, he won a scholarship and was also awarded a gold medal for an essay in Latin. Continuing his education with a scholarship at New College, Oxford, he graduated with a second-class Bachelor of Arts degree in law and modern history in 1872. He had already passed the competitive examination for the Indian Civil Service (ICS) in 1871, entered it on 3 June 1873 and arrived in India on 24 October of that year.[3][4]

India: 1873–1885

His initial posting was to Midnapur in Bengal as an Assistant Magistrate and Assistant District Collector. The area was inhabited in part by forest tribes. He soon took to studying them and retained an interest in the anthropology of such tribes for the remainder of his life. He also became involved in William Wilson Hunter's Statistical Survey of India, which began in 1869, and was to be printed in the first edition of The Imperial Gazetteer of India, published in 1881. Hunter personally conducted the survey of Bengal, and the anthropological, linguistic and sociological accomplishments of Risley were recognised in February 1875 when he was appointed as one of five Assistant Directors of Statistics for Hunter's Survey.[3][4][5]

Risley compiled the Survey's volume covering the hill districts of Hazaribagh and Lohardaga, and both the literary style and subject knowledge shown in this work were to prove beneficial to his career. He became Assistant Secretary to the Government of Bengal and then, in 1879, was appointed as Under Secretary in the Home Department of the Government of India. In 1880 he returned to work at district level, at Govindpur, having married Elsie Julie Oppermann on 17 June 1879 at Simla. According to Crispin Bates, a historian of modern South Asia, Oppermann was an "erudite German"[6] and her linguistic proficiency helped Risley learn more about anthropology and statistics from non-English sources. The couple had a son and a daughter.[3][5]

To return to work in the districts was Risley's personal preference and was made despite his unusually rapid rise through the ranks. He went from Govindpur back to Hazaribagh and then, in 1884, to Manbhum, where he was charged with conducting an enquiry into land tenure arrangements.[3]

Ethnographic Survey of Bengal: 1885–1891

In 1885, Risley was appointed to conduct a project titled the Ethnographic Survey of Bengal, which Augustus Rivers Thompson, the Lieutenant-Governor of the Presidency at the time, believed to be a sensible exercise.[5] The Indian Rebellion of 1857 had come close to overturning Company rule in India, and the disruption led the British government to take over administrative control from the British East India Company. Members of the ICS such as Richard Carnac Temple thought that if further discontent were to be avoided, it was necessary to obtain a better understanding of the colonial subjects, particularly those from the rural areas.[7] As time went on, the ethnographic studies and their resultant categorisations were embodied in numerous official publications and became an essential part of the administrative mechanisms of the colonial government; of those categorisations it was caste that was regarded to be, in Risley's words, "the cement that holds together the myriad units of Indian society".[8][9] The desire for ethnographic studies was expressed by another Raj administrator, Denzil Ibbetson, in his 1883 report on the 1881 census of Punjab:

Our ignorance of the customs and beliefs of the people among whom we dwell is surely in some respects a reproach to us; for not only does that ignorance deprive European science of material which it greatly needs, but it also involves a distinct loss of administrative power to ourselves.[10]

Risley's survey task was aided when research papers of a recently deceased Indian Medical Service doctor, James Wise, were given to him by the doctor's widow. Wise had researched the people of Eastern Bengal and it was agreed that, after ascertaining the accuracy of his work, his research should be incorporated into Risley's survey results. In return, those volumes of the survey dealing with ethnographic matters would be dedicated to Wise. Further assistance came from the research of Edward Tuite Dalton into the jungle tribes of Chhotanagpur and Assam. Dalton, like Wise, had previously published his efforts but now they would be integrated as a part of a larger whole. Risley was able to deal with the remaining areas of Bengal by making use of a large staff of correspondents who came from disparate backgrounds, such as missionaries, native people and Government officials.[5]

In 1891 Risley published a paper entitled The Study of Ethnology in India.[11] It was a contribution to what Thomas Trautmann, a historian who has studied Indian society, describes as "the racial theory of Indian civilisation". Trautmann considers Risley, along with the philologist Max Müller, to have been leading proponents of this idea which

by century's end had become a settled fact, that the constitutive event for Indian civilisation, the Big Bang through which it came into being, was the clash between invading, fair-skinned, civilized Sanskrit-speaking Aryans and dark-skinned, barbarous aborigines.[12][lower-alpha 1]

Trautmann notes, however, that the convergence of their theories was not a deliberate collaboration.[14]

In the same year, 1891, the four volumes of The Tribes and Castes of Bengal were published. These contained the results of the Bengal survey, with two volumes comprising an "Ethnographical Glossary", and a further two being of "Anthropometric Data".[lower-alpha 2] Risley took advice from William Henry Flower, Director of the Natural History Museum, and William Turner, an Edinburgh anthropologist, in compiling the anthropometric volumes. The work was well received by the public and government alike. In the same year, he was elected an officier of the Académie Française; and in the 1892 New Year Honours he was appointed a Companion of the Indian Empire (CIE).[3][15] In more recent times, his use of contemporary anthropometric methods has led to his career being described by Bates as "the apotheosis of pseudo-scientific racism",[16] an opinion that is shared by others.[17] The theory now known as scientific racism was prevalent for a century from around the 1840s[18] and had at its heart, says Philip D. Curtin, that "race was one of the principal determinants of attitudes, endowments, capabilities and inherent tendencies among human beings. Race thus seemed to determine the course of human history."[19]

According to Trautmann, Risley believed that ethnologists could benefit from undertaking fieldwork. He quotes Risley saying of ethnologists in India that they had relied too much:[20]

on mere literary accounts which give an ideal and misleading picture of caste and its social surroundings. They show us, not things as they are, but things as they ought to be, in the view of a particular school or in the light of a particular tradition ... [S]ome slight personal acquaintance with even a single tribe of savage men could hardly fail to be of infinite service to the philosopher who undertakes to trace the process by which civilisation has been gradually evolved out of barbarism.[11]

Risley also viewed India as an ethnological laboratory, where the continued practice of endogamy had ensured that, in his opinion, there were strict delineations of the various communities by caste and that consequently caste could be viewed as identical to race. Whereas others, such as Ibbetson, considered caste to be best defined as based on occupation, he believed that changes in occupation within a community led to another instance of endogamy "being held by a sort of unconscious fiction to be equivalent to the difference of race, which is the true basis of the system."[14][21] The study was, in the opinion of William Crooke, another ethnographer of the Raj period, "the first attempt to apply, in a systematic way, the methods of anthropometry to the analysis of the people of an Indian Province."[5][lower-alpha 3] Risley was influenced by the methodology of the French physical anthropologist Paul Topinard, from whose Éléments d'anthropologie générale he had selected several anthropometric techniques, including the nasal index. Topinard believed that this index – a ratio derived from measuring the breadth and height of the nose – could be combined with other cranial measurements to enable a Linnean classification of humans, for which purpose Trautmann said:

[I]t is useful both in its exactness of application and in the reassuring way in which it conforms itself to what is already known to be true rather than presenting us with information that requires us to part with existing beliefs.[23]

Despite his comments regarding the use of literature by anthropologists, Risley used the ancient Rig Veda text, which he interpreted as speaking of Aryan invaders coming into India from the northwest and meeting with existing peoples. Dalton and J. F. Hewitt had posited that the native people comprised two distinct groups, being the Dravidian and the Kolarian, and Risley's use of the nasal index was in part intended to counter those theories by showing that the two groups were racially identical even if they were linguistically varied.[24] Crooke noted that Risley appeared to succeed in proving a physical similarity between "the so-called Dravidian and Kolarian races" and "identified the Austro-Asiatic group of languages, with Munda as one of its sub-branches."[5]

Risley's interpretation of the nasal index went beyond investigation of the two-race theory. He believed that the variations shown between the extremes of those races of India were indicative of various positions within the caste system,[25] saying that generally "the social position of a caste varies inversely as its nasal index."[26] Trautmann explains that Risley "found a direct relation between the proportion of Aryan blood and the nasal index, along a gradient from the highest castes to the lowest. This assimilation of caste to race ... proved very influential."[27] He also saw a linkage between the nasal index and the definition of a community as either a tribe or a Hindu caste[25] and believed that the caste system had its basis in race rather than in occupation, saying "community of race, and not, as has frequently been argued, community of function, is the real determining principle, the true causa causans, of the caste system."[28]

The methods of anthropometric data collection, much of which was done by Risley, have been questioned in more recent times. Bates has said:

The maximum sample size used in Risley's enquiry was 100, and in many cases Risley's conclusions about the racial origins of particular castes or tribal groups were based on the cranial measurements of as few as 30 individuals. Like Professor Topinard, Paul Broca, Le Bron and Morton before him, Risley had a clear notion of where his results would lead, and he had no difficulty in fitting the fewest observations into a complex typology of racial types.[29]

India: the 1901 census

After completing the Bengal survey, Risley's work consisted of heading an enquiry into policing, and following that more usual administrative tasks for both the Bengal and Imperial governments. In 1899 he was appointed Census Commissioner, tasked with preparing and reporting on the forthcoming decennial census of 1901. The detailed regulations that he formulated for that exercise were also used for the 1911 census, and the work involved in co-ordinating the various Provincial administrations was considerable and detailed.[5] He succeeded Jervoise Athelstane Baines, who held the office for the 1891 census, had himself adjusted the classification system and was an influence on Risley.[30] According to political scientist Lloyd Rudolph, Risley believed that varna, however ancient, could be applied to all the modern castes found in India, and "[he] meant to identify and place several hundred million Indians within it."[31]

The outcome of the census is described by Crooke as "an exceptionally interesting report", produced in association with a colleague, Edward Albert Gait. Crooke notes that in the report "he developed his views on the origin and classification of the Indian races largely on the basis of anthropometry."[5] By now, Risley believed anthropometric measurement enabled the Indian castes to be described as belonging to one of seven racial types, although he accepted that his own work indicated only three such types: the Aryan, Dravidian and Mongoloid. The seven that he believed to be capable of classification were the Aryo-Dravidian, Dravidian, Indo-Aryan, Mongolo-Dravidian, Mongoloid, Scytho-Dravidian and the Turko-Iranian.[29] He went further still by holding that there was support for the racial theory in the various linguistic differences between Indian communities, an opinion that frustrated Müller but which was supported by the publication of the Linguistic Survey of India by another officer of ICS, George Abraham Grierson. Bates notes that the correlation in the theories of Risley and Grierson is not surprising because Grierson was

armed with the much earlier but as yet unproven hypotheses of Sir William Jones concerning matters of language and race, and was intimately acquainted with Risley's theories of racial origins. Grierson also followed a similar ex ante deductive methodology in his research.[32]

Another event that occurred in 1901 and which related to Risley was the official approval of an India-wide ethnographic survey, intended to be conducted over a period of eight years and using in part the anthropometrical methodology established for Risley's survey of Bengal. Superintendents were appointed to each Province and Presidency and grants of £5000 per annum were given for the eight-year period. Bates considers that the results of this effort, which included works by Edgar Thurston and Robert Vane Russell, were rarely "quite so thorough, even by Risley's standards."[33][lower-alpha 4]

Some of the material from the 1901 census was later republished, in amended form, in Risley's 1908 work, The People of India, which sociologist D. F. Pocock describes as "almost the last production of that great tradition of administrator scholars who had long and extensive experience in the Indian Civil Service and had not found their arduous activity incompatible with scholarship."[34] Trautmann considers the census report and subsequent book to represent "Risley's grand syntheses of India ethnology", while the paper of 1891 had given "an exceptionally clear view of his project at the state of what we might call its early maturity."[14]

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) says:

From the date of his report a new chapter was opened in Indian official literature, and the census volumes, until then regarded as dull, were at once read and reviewed in every country. His categorisation of Indian castes and occupations had an enduring social and political effect.[3]

According to Susan Bayly, who studies historical anthropology:

Those like [Sir William] Hunter, as well as the key figures of H. H. Risley (1851–1911) and his protégé Edgar Thurston, who were disciples of the French race theorist Topinard and his European followers, subsumed discussions of caste into theories of biologically determined race essences ... Their great rivals were the material or occupational theorists led by the ethnographer and folklorist William Crooke (1848–1923), author of one of the most widely read provincial Castes and Tribes surveys, and such other influential scholar-officials as Denzil Ibbetson and E. A. H. Blunt.[35][lower-alpha 5]

India: later years

In 1901 Risley was appointed Director of Ethnography.[3] There had been proposals for a wide-ranging survey of the subject – which Risley had himself discussed this in his article, The Study of Ethnology in India – but the implementation of the project had been hampered by economic circumstances related principally to a series of famines, including that of 1899–1900.[5]

In the following year he became Home Secretary in India in the administration of Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India, and in 1909 was temporarily a member of the governing council. His experience of administrative matters, including with regard to policing, proved to be useful to Curzon during the government's 1905 partition of Bengal along communal lines. So useful was his knowledge and ability that his term in India was extended for two years beyond the usual retirement age. This was to enable him to provide the summarisation, negotiation and drafting skills necessary to ensure success in administrative reform of the Provincial Councils by Curzon's successor as Viceroy, Lord Minto.[3]

Already recognised by the Académie Française and by the award of CIE, Risley was made a Companion of the Order of the Star of India on 24 June 1904 and a Knight of the Order of the Indian Empire in 1907.[5][15]

The ODNB notes that during his time in India Risley's work legitimised an inquisitive methodology which had previously been resented by the colonial subjects and that

[Risley] cultivated an intimate knowledge of the peoples of India. In 1910 he asserted that a knowledge of facts concerning the religions and habits of the peoples of India equipped a civil servant with a passport to popular regard. ... On the processes by which non-Aryan tribes are admitted into Hinduism he was recognized to be the greatest living authority ... His work completely revolutionized the native Indian view of ethnological inquiry.[3]

England, and death

Back in England, having left the ICS in February 1910,[5] Risley was appointed Permanent Secretary of the judicial department of the India Office, succeeding Charles James Lyall.[36] In January of that same year he became President of the Royal Anthropological Institute.[3]

According to Crooke, "the strain of [overseeing the Provincial Council reforms] on a constitution which at no time was robust doubtless laid the seeds of the fatal disease which was soon to end his life." Risley died at Wimbledon on 30 September 1911, continuing his studies to the end despite suffering what the ODNB describes as a "distressing illness". His widow was remarried to Lieutenant-General Sir Fenton Aylmer; she died in 1934.[3]

References

Notes

- Sir William Jones had first proposed a racial division of India as a consequence of an Aryan invasion but at that time, in the late 18th century, there was insufficient evidence to support it.[13]

- This was the first time that anthropometry was used in a survey of Indian people.[6]

- William Crooke's comment regarding Risley being the first to attempt a systematic use of anthropometric methods in India does not necessarily signify approval of those methods. Crooke was a folklorist and, according to Bates, "his principal rival and critic at this time".[22]

- The ethnography documented by Edgar Thurston (1855-1935) most notably related to South India; that of Robert Vane Russell (1873-1915) focussed on the Central Provinces.

- E. A. H. Blunt (1877-1941) worked mostly in the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh and wrote of the people in that Province.

Citations

- Trautmann (1997), p. 203.

- Walsh (2011), p. 171.

- "Risley, Sir Herbert Hope". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35760. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- The India List and Office List. India Office. 1905. p. 600.

- Risley, Sir Herbert Hope (1915) [1908]. Crooke, William (ed.). The People of India (Memorial ed.). Calcutta: Thacker, Spink.

- Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter (ed.). The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0.

- Naithani, Sadhana (2006). In quest of Indian folktales: Pandit Ram Gharib Chaube and William Crooke. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34544-8.

- Metcalf, Thomas R. (1997). Ideologies of the Raj. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-521-58937-6.

- Risley, Sir Herbert Hope (1915) [1908]. Crooke, William (ed.). The People of India (Memorial ed.). Calcutta: Thacker, Spink. p. 278.

- Ibbetson, Denzil Charles Jelf (1916). Panjab Castes. Lahore: Printed by the Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab. p. v. of Original Preface.

- Risley, Herbert Hope (1891). "The Study of Ethnology in India". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 20: 237–238. doi:10.2307/2842267. JSTOR 2842267.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (2006) [1997]. Aryans and British India (2nd Indian ed.). New Delhi: YODA Press. p. 194. ISBN 81-902272-1-1.

- Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter (ed.). The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (2006) [1997]. Aryans and British India (2nd Indian ed.). New Delhi: YODA Press. p. 199. ISBN 81-902272-1-1.

- The India List and Office List. India Office. 1905. p. 167.

- Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter (ed.). The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0.

- Schwarz, Henry (2010). Constructing the Criminal Tribe in Colonial India: Acting Like a Thief. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-4443-1734-3.

- Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, P. (ed.). The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0.

- Curtin, Philip D. (1964). The Image of Africa: British Ideas and action, 1780–1850. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-8357-6772-9.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (2006) [1997]. Aryans and British India (2nd Indian ed.). New Delhi: YODA Press. p. 198. ISBN 81-902272-1-1.

- Risley, Herbert Hope (1891). "The Study of Ethnology in India". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 20: 240. doi:10.2307/2842267. JSTOR 2842267.

- Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter (ed.). The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (2006) [1997]. Aryans and British India (2nd Indian ed.). New Delhi: YODA Press. pp. 200–201. ISBN 81-902272-1-1.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (2006) [1997]. Aryans and British India (2nd Indian ed.). New Delhi: YODA Press. pp. 202–203. ISBN 81-902272-1-1.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (2006) [1997]. Aryans and British India (2nd Indian ed.). New Delhi: YODA Press. p. 203. ISBN 81-902272-1-1.

- Risley, Herbert Hope (1891). "The Study of Ethnology in India". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 20: 253. doi:10.2307/2842267. JSTOR 2842267.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (2006) [1997]. Aryans and British India (2nd Indian ed.). New Delhi: YODA Press. p. 183. ISBN 81-902272-1-1.

- Risley, Herbert Hope (1891). "The Study of Ethnology in India". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 20: 260. doi:10.2307/2842267. JSTOR 2842267.

- Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter (ed.). The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0.

- R.H.R.; S. de J. (January 1926). "Obituary: Sir Athelstane Baines, C.S.I.". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. London: Royal Statistical Society. 89 (1): 182–184. JSTOR 2341501.

- Rudolph, Lloyd I. (1984). The Modernity of Tradition: Political Development in India. Rudolph, Susanne Hoeber. University of Chicago Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 0-226-73137-5.

- Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter (ed.). The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0.

- Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter (ed.). The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0.

- Bouglé, Célestin Charles Alfred (1971). Pocock, D. F. (ed.). Essays on the caste system. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. viii–ix. ISBN 978-0-521-08093-4.

- Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. The New Cambridge History of India, Volume 4.3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-0-521-26434-1.

- Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter (ed.). The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0.

Further reading

- Raheja, Gloria Goodwin (August 1996). "Caste, Colonialism, and the Speech of the Colonized: Entextualization and Disciplinary Control in India". American Ethnologist. 23 (3): 494–513. doi:10.1525/ae.1996.23.3.02a00030. JSTOR 646349.

- Inden, Ronald (2001). Imagining India. Indiana University Press. pp. 57–66. ISBN 978-0-253-21358-7.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (1997), Aryans and British India, Vistaar

- Walsh, Judith E. (2011), A Brief History of India, Facts On File, ISBN 978-0-8160-8143-1