Herbesthal railway station

Herbesthal railway station was the Prussian/German frontier station on the main railway from Germany into Belgium between 1843 and 1920. It opened to rail traffic on 15 October 1843,[1] and was thereby the oldest railway station frontier crossing in the world. It lost its border status on 10 January 1920, however, as a result of changes mandated in the Treaty of Versailles, which left Herbesthal more than 10 km (6.2 mi) inside Belgium.[2]

Herbesthal railway station Bahnhof Herbesthal | |

|---|---|

| Frontier station | |

Herbesthal railway station (ca 1900) | |

| General information | |

| Location | Herbesthal (Lontzen), Prussia (1843–1871) Germany (1871–1920) Belgium (1920–1966) |

| Coordinates | 50°39′37.8″N 5°59′10.7″E |

| Platforms | 7 |

| History | |

| Opened | 1843 |

| Location | |

Herbesthal railway station (1843–1966) Location within Belgium | |

Description

The station reached its maximum extent following a major redevelopment in 1889. This left it with five mainline platforms (numbered 1–5) and, on the south side of these, two branch line platforms (numbered 12 & 13) for the local service connecting Eupen with the main line.[2] The mainline platform by the newly, in 1889, rebuilt and enlarged station building, had a canopy: the other mainline platforms acquired canopies later.

After the closure of the station in 1966 the platforms were quickly torn up, but the main station building remained, standing empty for many years. Eventually, despite local protests, the main station building itself was torn down in 1983. All that now (2014) remains visible is a couple of foundation stones and steps.[3] During the summer of 2014 the local municipality organised an exhibition on the site, dedicated to the station's history.[4] Plans exist for a more permanent display or exhibition centre.[5]

The goods station was located to the west of the passenger station. After the closure of the passenger station in 1966 part of the goods station was reallocated to Welkenraedt station, a short distance down the line. However, with transport users increasingly favouring roads, Welkenraedt lost its goods station during the 1980s. In 2012 the municipality decided to renovate and reassign some of the abandoned railway buildings. One of them is used for a Youth Club.[6]

History

Construction and operation by the Rhine Railway Company <1843-1880

Belgium was the second country to start building a railway network, and plans drawn up for a national network in the 1830s already envisaged a connection to Cologne so that industry in Belgium could have a transport link through to the rapidly industrialising Ruhr region in western Prussia without incurring the intervening cost of high Dutch tolls.[2] On the Prussian side of the border the industrialist-investors David Hansemann and Gottfried Ludolf Camphausen seized eagerly on the idea. The Rhine Railway Company ("Rheinische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft") obtained the king's agreement in 1837 to the construction of a rail link from Cologne to Aachen, crossing into Belgium at the frontier on the edge of Herbesthal. Herbesthal was a small village of around 300 people, and an earlier idea had been to have the frontier at Eupen, a more substantial town also, then, on the frontier, but this idea had to be rejected for topographical reasons. The company therefore undertook to build a rail link from the proposed mainline to Eupen. The Rhine Railway Company agreed with the Belgian National Railway Company to construct a joint frontier facility at Herbesthal where necessary customs clearance could be undertaken by officials from both countries.

Herbesthal thereby became noteworthy as Europe's first international frontier railway station. The line from Cologne as far as Aachen was inaugurated in 1841, but construction progressed more slowly through the hills to the west of Aachen, above all because of the time needed to build the Ronheider incline, the 700 metres (2,297 ft) long Busch Tunnel and the 200 metres (656 ft) long Hammer Rail Viaduct over the Geul River south of Hergenrath. However, on 15 October 1843 the line was opened from Aachen to Herbesthal, and two days later from Herbesthal to Verviers. Verviers had had a rail link to Liège since July. The entire length of line from Aachen to Liège entered into service on 24 October 1843, and quickly became part of one of the most important international rail routes in western Europe.

Initially Herbesthal station was a shared responsibility, administered both from Ronheide Station at the top of the Ronheider incline and from Verviers in Belgium. The Rhine Railway Company provided the railcars and train staff while the Belgian State Railway company provided the locomotives.[2] For the Ronheider incline itself the trains were initially hauled up the slope using a cable powered by a static steam engine. The system proved troublesome and costly in operation, however, and was abandoned little by little, so that after 1854 trains on the incline were always hauled by a conventional locomotive intended to operate with sufficient power to manage the slope.[2] Around this time the station at Herbesthal was expanded to provide space for locomotives to be switched so that during the ensuing decades Prussian locomotives provided the traction in Prussia and Belgian locomotives in Belgium. A few years later Welkenraedt station was built on the Belgian side of the frontier. Between the two stations there were less than 200 metres (656 ft) of open track, however: locomotive changes and customs/frontier administration continued to be focused on Herbesthal.

Twenty years after Herbesthal station, the promised branch line to Eupen was opened, on 1 March 1864: Herbesthal station was extended to accommodate the new service.[2] The little rail depot at the station probably also dates from this period.[2]

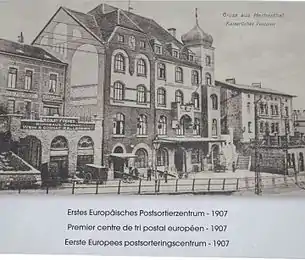

By now a post office had been built at the station, relocated in 1855 from Henri-Chapelle on instructions from the regional head post office at Aachen. At Herbesthal this quickly became one of Europe's busiest mail depots. In 1890 the postal facilities were relocated to a new purposes built post office building beside the station, which would be taken over by the Belgian postal administration in 1920. During the 1920s up to 1,000 mail bags were processed here daily, and it was only after the introduction of so-called mobile sorting offices, using dedicated rail-cars, that the postal facilities at Herbesthal station were removed.

Rail nationalisation and expansion 1880–1914

Despite bitter opposition from company president Gustav von Mevissen, the Rhine Railway Company was nationalised in 1880. Company assets, including the station at Herbesthal, were taken over by the Royal Railway Directorate of "Cöln" (Rhine Leftbank Operations) (" Königliche Eisenbahndirection zu Cöln (linksrheinische)" / KED) based in Cologne.[2]

The KED implemented a complete renovation of the station in 1889. The facilities built up over previous decades were no longer able to accommodate the escalating needs. The goods station was expanded, the depot receiving two extra "ring-form" parking slots for locomotives accessible using a new turntable. Two years earlier the branch line to Eupen had been extended to Raeren where it now linked up with the Vennbahn (railway).

The station received a large new passenger building to cope with growth in passenger numbers. There were new facilities for police, customs and frontier officials and separate waiting rooms for each passenger class. There was also a so-called "Prince's Waiting Room" reflecting the importance of international rail travel generally, and of the frontier station more specifically, even for monarchs and their extended families. England's Queen Victoria undertook her first rail journey via the Herbesthal frontier station in 1845, accompanied by her consort.[4] Thirteen years later, in early 1858 the British monarch's eldest daughter passed through Herbesthal with her new husband en route to a new home in Germany where thirty years later they would briefly become empress and emperor.[4] Between the British and German (and other) royal families there was a large and proliferating network of kinship connections which would ensure regular use of the "Prince's Waiting Room" during the closing years of the nineteenth century.

From the mid-1890s there were newly introduced high-profile luxury services, the Ostend-Vienna Express and the Northern Express, stopping for customs clearance at Herbesthal. It was also on a main route for passenger express services from Belgium, the Rhineland and northern France. As well as this, the station was important for increasing volumes of freight traffic, even though some westbound trains were routed to avoid the southbound stretch because of the gradient of the Ronheider incline south of Aachen.

The First World War and its aftermath 1914–1944

On 2 August 1914 war on the western front was launched with a German invasion of Luxembourg, although it was only on 4 August 1914 that Germany declared war on Belgium. In the Edinburgh Evening News a reader provided a vivid account of her problem-free crossing of the frontier at Herbesthal from Germany into Belgium during the early morning hours of 2 August 1914.[7] Nevertheless, the outbreak of war brought an end to civilian passenger transport, and the border crossing passed from the control of the national railway company into that of the army, who also took control of the railways in occupied Belgium. Herbesthal became critically important as a transit location and as a replenishment location for the armies on the western front. At the same time, thousands of wounded soldiers stranded on the way home from the front received medical care and treatment here. Additionally, more than 70,000 forced labourers from Belgium were channeled into Germany through Herbesthal. Towards the end of the war the station fell into the hands of plunderers returning from the front. Herbesthal station became the focus of so much congestion that an alternative less southerly route, today known as the Montzen route, was constructed by the Germans between 1915 and 1917, entering occupied Belgium from Aachen via Tongeren, completely avoiding Herbesthal and, indeed, Liège.

War ended in defeat in November 1918, to be followed by revolution and republican government at home, and the Treaty of Versailles drawn up in France. Eupen and Malmedy were transferred from Germany to Belgium, along with the adjacent enclave of Moresnet which had enjoyed a strangely ambiguous political status since 1816. The border changes were mandated in 1919 and their implementation began in January 1920. The actual frontier moved a short distance up the line to the southern entrance of the (subsequently renewed) Busch Tunnel. Herbesthal now found itself transported into Belgium. Nevertheless, until 1940 it continued to operate as the frontier station on the mainline, with the difference that now the customs and passport officials were working on the Belgian side of the frontier for the Belgian government. Directly following the war there were relatively few "stopping trains" carrying passengers beyond Herbesthal into Germany using the new German frontier control station near the hamlets at Astenet and Hergenrath. However, passenger traffic slowly recovered through the 1920s. The Ostend-Vienna Express and the Northern Express returned and were joined in 1929 by a third luxury express service, the Ostend-Cologne Pullman Express, though only the eastbound trains took the route passing through Herbesthal. During the 1920s Herbesthal increasingly lost one of its important pre-war functions, with the train operators now switching between Belgian and German locomotives not at the frontier but at Aachen.

Belgium was again invaded by German troops in May 1940, although developments in motor transport during the previous two decades meant that the generals were no longer quite so dependent on the rail network as they had been for the First World War. During approximately 52 months of German occupation Herbesthal temporarily recovered its status as the German frontier station.

Postwar revival

After 1945 it was again the SNCB (National Railway Company of Belgium) using Herbesthal as their frontier station. In contrast to the position before the war, there were now no local trains operating to Aachen. Locomotive switching between Belgian and German locomotives returned to Hebesthal. It was not till 1947 that, initially only for a small number of trains, operators reverted to switching locomotives at Aachen, and Herbesthal retained its importance as the principal locomotive switching location through most of the 1950s.

Before the war the locomotives housed and maintained at Herbesthal had been those used for local passenger and goods trains, but during the later 1940s there were fewer of these, initially because of austerity and then during the 1950s because of the growth in road transport. Herbesthal now became the home deport for the "Pacific class" NMBS/SNCB Type 1s, built in the late 1930s but still used for the prestigious international luxury trains, and during the 1950s the most powerful high speed steam locomotive used in Belgium. Herbesthal was again one of the most important frontier stations in western Europe. Not only the Northern Express, but also the Tauern Express were now making the switch between German and Belgian locomotives at Herbesthal. When the Trans Europ Express (TEE) network was set up in 1957, Herbesthal was where Belgian TEE train staff took over the railcars for the Belgian sections.

Electrification

Towards the end of the 1950s both the West German state railways (DB) and the Belgian state railways (SNCB) started planning for electrification. Belgium was committed to a 3 kW DC network while the Germans had opted for a 15 kW AC power supply. At this stage dual-voltage and multi-voltage locomotives were far from mainstream in Europe, which imposed a greater level of inflexibility on decisions about where to change power supply systems and locomotives. In the end the decision was taken that for trains operating along the line from Liège to Aachen, switching of the power supply and locomotives should be centralised some distance inside Germany, at Aachen, where the equivalent switch would also be made for trains coming from the Netherlands. An added advantage of choosing Aachen was that many international passenger trains were already held up there while being reconfigured, as blocks of carriages from the directions of Rotterdam and Brussels were split or merged for the next part of their journeys across Germany. Where this happened there was little or no incremental time-cost involved in switching locomotives at the same time. Work began on electrification of main lines in 1961, and this immediately involved some of the international trains headed towards Brussels and Ostend being rerouted onto the Montzen Route to the north, thereby avoiding Herbesthal completely. Passenger services along the branch line to the east, via Eupen to Raeren in Germany had already been ended on 28 March 1959, so that by 1961 Herbethal had also lost its function as an interchange station.

Language politics

Within Belgium the 1950s saw a growth in friction between Dutch speakers and French speakers over language usage. Legislation came into operation in 1962 that divided Belgium into four language areas. The largest two areas, and those with the greatest political muscle, were the Flemish speaking area centred on Ghent, Antwerp and Hasselt, and the French speaking area centred on Charleroi and Liège. The city of Brussels had language issues of its own. and was defined as a third language area, while there was a very small fourth language area in the extreme east of the country, made up essentially of the land confiscated from Germany in 1920, where the dominating language was still German. Herbesthal was in the small German speaking enclave, while 200 meters to the west Welkenraedt was in the French language area. Although passport and customs checks were by now increasingly conducted by officials as the train continued on its way, there remained a need for administrative offices on each side of the frontier. For the Liège/Aachen international line these were increasingly focused on Aachen itself on the German side of the frontier, while on the Belgian side, following the definition of more clearly delineated language zones, customs and passports offices were relocated a couple of hundred meters to the west to francophone Welkenraedt, which left the station at Herbesthal looking ever more unnecessary.[2]

Closure

The electrification project was completed on the line and the electrified traction system commissioned on 22 May 1966. Herbesthal station was formally closed on 7 August 1966.[2] By this time the station's rail depot had been largely closed. A few sidings which had comprised the western section of the Herbesthal depot were reassigned to the adjacent station at Welkenraedt.

Locomotive depot

There would have been some sort of locomotive storage facility at Herbesthal from the start, but the locomotive depot was greatly expanded following the takeover by what became the Prussian State Railway company and the redevelopment on the Herbesthal site undertaken in 1889. By 1920, directly before the frontier shifted and the station was transferred to Belgium, Prussian locomotives housed and maintained at Herbesthal included Type P8s, old Type T9s and older Type T3s.

When the (Belgian) SNCB took over, they transferred engines from their existing smaller engine depot at Welkenraedt, where the locomotive depot was closed down. As part of the reparations package agreed by the victorious powers a large number of formerly German locomotives were transferred to Belgium in 1920, and through the 1920s many of the Belgian locomotives stored at Herbesthal were ones that had originally operated in Germany. These included Belgian Type 81 (previously Prussian Type G8.1)s, Belgian Type 93 (previously Prussian Type T9.3)s and Belgian Type 97 (previously Prussian Type T14)s. The Herbesthal locomotive fleet also included Belgian built Type 7s and, after 1945, Type 29s. Through the 1920s and 1930s, however, the heavy luxury international express services from Ostend were generally hauled by locomotives maintained at the depots in Liège and Brussels.[2]

After 1945 Herbesthal became the home deport for the "Pacific class" NMBS/SNCB Type 1s, used for the prestigious international luxury trains.

References

- Leo Kever (9 March 2013). "Seit 1843 führt eine der wichtigsten Eisenbahnverbindungen über Herbesthal". Grenz-Echo AG, Eupen. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- Hans Schweers; Henning Wall (1993). Eisenbahnen rund um Aachen: 150 Jahre internationale Strecke Köln – Aachen – Antwerpen. Verlag Schweers + Wall, Aachen. ISBN 3-921679-91-5.

- "Bahnhof Herbesthal stellt 100 Jahre alte Waggons aus". Belgisches Rundfunk- und Fernsehzentrum der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft (BRF), Eupen. 25 July 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "Die faszinierende Geschichte des Bahnhofs Herbesthal wird wieder lebendig .... Einer der schönsten Bahnhöfe in Europa". Ostbelgien Direkt Media (GenmbH), Eupen. 3 February 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "Erinnerungen an Ersten Weltkrieg am Bahnhof Herbesthal und im Weißen Haus". Grenz-Echo AG, Eupen. 31 July 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "Lontzen: Bahnhofsgelände Herbesthal wird saniert". Belgisches Rundfunk- und Fernsehzentrum der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft (BRF), Eupen. 27 November 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Edinburgh Evening News – Tuesday 4 August 1914